Part Three

Gallery

Ultimately a picture must stand on its own merit. All the effort that went into making it – the photographic techniques, the equipment used and the lengths the photographer had to go to – is irrelevant. Some pictures come easily, when Mother Nature smiles and all the elements come together seemingly effortlessly. More usually the strongest images represent triumphs of perseverance, or fleeting moments of perfection.

Sometimes after waiting for the light for hours or even days, a splash of light paints the landscape for just 30 seconds, and I only manage to expose two or three frames. As the clouds close in again, I am often left wondering, did I get it? How were my exposures? It’s good to be your own harshest critic, to be constantly striving to improve, but there also comes a time to trust your vision and experience, and move on to the next image.

Trotternish Peninsula, Isle of Skye, Scotland

• Fuji GX617, 180mm lens

Durdle Door, Dorset, England

My grandfather used to patrol these very cliff tops in the Home Guard. At least that’s what he told us; my mother reckoned they were mostly in the pub. After a lifetime of travel I’ve returned to my roots, here in Dorset. It’s important to feel you come from somewhere. This stretch of coast, which we’ve always known is spectacular, is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site, the Jurassic Coast, ranking alongside the Grand Canyon and the Great Barrier Reef. This is one of my most popular images; it has sold all over the world, and hangs over many fireplaces, which, considering my photography covers all four corners of the globe, says something.

• Fuji GX617, 105mm lens

St Michael’s Mount, Cornwall, England (David Noton/National Trust)

Over the course of this summer I’ve become a little bit obsessed with St Michael’s Mount. I’ve visited several times to shoot in different combinations of tide and light. Here, on a long evening in June, the sun is setting way to the northwest, giving perfect cross lighting. I’m using a 0.9 ND filter to slow down the exposure as much as possible, in conjunction with an aperture of f/45, a centre-weighted 0.3 ND to even the coverage of this wide format and ISO 50 film, which all cooks up an exposure of about 15 minutes. Additionally, I’ve got yet another filter on, a 0.9 ND graduate to hold back the exposure of the sky in relation to the water. This is my most used filter; it’s employed on probably two-thirds of all my shots. The tide is going out, gradually exposing the causeway, leading the eye towards the mount. As I idle the time away while the shutter is open, I’m pondering all these factors: the depth of field, the exposure, the filtration, the colour temperature of the light and the composition, while weighing the overall impact of the image. The making of a photograph is a fusion of science and art.

• Fuji GX617, 90mm lens

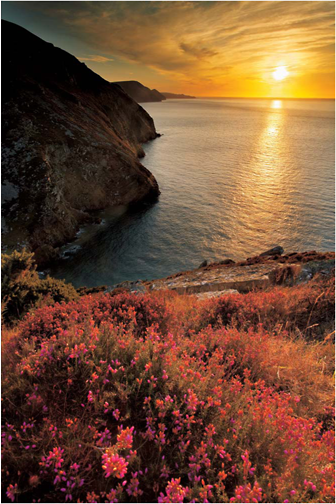

Coastal heath on the cliffs of Highveer Point above Heddon’s Mouth, near Lynton, North Devon, England

In late summer on the North Devon coast the colours are incredible. Where Exmoor tumbles into the sea the coastal path is fringed with dense profusions of bell heather. I’ve timed my visit to coincide with this harvest of colour, but photographing a north-facing English coast in September is not easy. At this time of year, the sun rises exactly to the east, and sets bang on due west. So, on a north-facing coast at dawn and dusk I’m either going to be shooting straight into the light or have it coming from directly behind me, and during the day the sun will swing round to the south, casting the cliffs in shadow. It’s hardly ideal. Purely in terms of the light the ideal time to photograph a northfacing coast is in late June, but the colours aren’t at their best then. For a photographer it is vital to know exactly where the sun is going to rise and set and the effect of the seasons. So, here on the cliff tops in Devon the sun is dropping and I’m shooting straight into it. It’s a scenario beset with problems: flare from the power of the sun boring straight into the lens and bouncing about between the elements, and the contrast between the light reflecting off the water and the detail in the cliffs. I wait until the sun is very low and starting to lose its punch, which solves the flare problem, but the contrast issue can only be resolved by shooting several exposures for the highlights, mid-tones and shadows and merging them later in the digital darkroom.

• Canon EOS-1Ds MKII, 17–40mm lens

Croome Park, Worcestershire, England (David Noton/National Trust)

With perfect reflections, a dramatic sky and a trace of mist lying on the lake, conditions don’t really get any better. The sun beams through the trees; at moments like this there are just too many options. If I were shooting film I’d be struggling to get it through the camera quickly enough, wasting precious time doing bracketed exposures and reloading just when the light’s at its best. But I’m not, and shooting digitally in situations like this really pays off. I shoot one frame and quickly check the monitor. A blinking display alerts me to some loss of detail where the highlights are burning out around the sun, I re-adjust my exposure by -2/3 and shoot another, check highlights and histogram, it’s in the can, or rather, on the card. Just two exposures. I can now move on to framing other images, making the most of this beautiful English scene at dawn.

• Canon EOS-1Ds MKII, 17–40mm lens

Buttermere, Lake District, Cumbria, England

It’s one of those mornings when all my senses seem alive to the pleasures of autumn in the Lake District. The colours are at their prime, giving the landscape a russet golden tinge. The birdsong reverberates over the stillness of Buttermere. There’s dampness in the air you can almost touch and the woods smell of autumn. This is familiar stomping ground for many photographers, for good reason. I’ve worked here many times (I first came here on a college field trip as a photography student back in 1983), but it’s infinitely variable and I’ll probably be coming back way past my sell-by date. Now the first light is slowly creeping down the fell, but it has got a way to go yet, so I’m standing by the tripod, kicking my heels, scanning the sky to the east, thinking of my next meal, waiting for the light. I think I’ve spent half my life in this mode.

• Fuji GX617, 180mm lens

Salisbury Cathedral at dawn, Wiltshire, England (David Noton/Britainonview.com)

I waited all summer for these perfect conditions: the still, settled conditions of a high pressure system laying mist over the water meadows around Salisbury Cathedral. Then over the course of two subsequent dawns I turned out to do the job. On the first dawn I saw where the mist was lying and made some reasonable images, but I left with a nagging thought that I hadn’t quite made the most of the situation. And so the following morning, a summer Sunday at 5am, I was there again. Pre-visualization, persistence, and Being There … it works.

• Canon EOS 1Ds MkII, 16–35mm lens

Bamburgh Castle, Northumberland, England

Northumberland is a beautiful county: sweeping open beaches overlooked by castles, big skies and rolling countryside. I often chop and change between formats depending on my vision. Some locations just cry out for a panoramic approach, and this is one. Now though I’m winding the exposed 220 film through the panoramic camera, contemplating my next move, as the best of the predawn glow is over. As the sun pops over the horizon, high-altitude cloud masks its direct light, but this cloud, which was previously ‘shepherd’s delight’, is now part of a monochromatic masterpiece of tones and reflections. With a solitary figure (you know who again) reflected in just the right place in the frame I expose a set with the digital camera. With the smaller format I can work much faster, be more spontaneous, investigate more alternatives and use a wider range of lenses and perspectives. The large panoramic format requires a more preconceived, considered approach. There’s a time and a place for both.

• Canon EOS-1Ds MKII, 17–40mm lens

The four seasons, Stourhead, Wiltshire, England

The autumn image came first. Stourhead in the fall is glorious, and after a particularly good session here the four seasons idea came to me. Thereafter it became an exercise in persistence and planning. Finding a location that will work in the different light of all the seasons is difficult. I lost count of how many times I visited in the making of this set. Winter was the tough one; thankfully I was in the country for one of the few frosty spells we had. The direction of the light in the early morning for the autumn and winter shots was perfect, a low cross light from the southeast. Spring and summer were much more difficult: with the sun rising to the northeast I had to wait until much later, about mid-morning, before the sun had swung around to the southeast. To have shot earlier would have given me flat frontal lighting, which I hate, but this way the sun was much higher than I would normally prefer. In the end it was a compromise. Summer came last, and when I finally printed the set side by side I got a buzz of satisfaction: a year’s work had come to fruition.

• Fuji GX617, 180mm lens

Poppies and barley blowing in the wind with la Cité Médiévale beyond, Carcassonne, Languedoc, France

Every time I check in for a flight the rules about what can be taken and how seem to have changed. It’s a big problem for photographers. Obviously it’s desirable to take it all as hand luggage, but that’s just not possible when there are long lenses, laptops and panoramic systems to take. Not to mention all the equipment needed for living and camping in the wilds. I hate having to debate whether to take my 400mm or not, and if it’s going to be a panoramic-type trip. With the change to digital I no longer have to travel with hundreds of rolls of film, but the number of chargers, cables and connectors I now need has mushroomed. Our annual timetable usually sees the winter months dominated by long-haul journeys to the tropics or southern hemisphere. In spring I often have a blitz on European cities. By May I’ve usually had my fill of airports and flight schedules. So when it’s time for another roving trip through the lanes of France or Italy you can imagine what a treat it is to be able to load the car with what we need and just go. We’ve stayed in this region near Carcassonne for over a week. That’s a bit longer than normal but there’s so much potential around the Canal du Midi I’m loath to move on. I’ve got a good stock of locations scouted; some will have to wait until our next visit.

• Canon EOS-1Ds MKII, 70–200mm lens

Cordes-sur-Ciel, Midi-Pyrénées, France

From the guidebooks, a friend’s testimony and pictures I’d seen, the bastide town of Cordes-sur-Ciel seemed a promising location. So, after a half-day drive from the Pyrenees we’re setting up camp just down the valley. After a couple of hours cycling around the periphery of the town I’ve sorted my morning location: an adjacent hill looking back at the quintessential French hilltop town. On my first morning there are clear skies apart from a rebel layer of cloud on the northeastern horizon, obstinately obscuring the rising sun. I hang around fruitlessly for a couple of hours, before heading for the boulangerie. The second dawn is clear, too clear. The light is low and directional, slightly hazy, and there’s not a cloud in the sky. Somehow, it’s just not coming together – there’s no drama to the image. On the third morning it’s mostly clear again, with scattered cloud – perfect – but by the time I’m in position I’m standing under leaden grey skies. It’s another fruitless vigil before heading for the croissants. On the fourth morning there’s broken cloud at 4am so here I go again. There’s a layer of mist lying in the valley. As the rising sun struggles to make an appearance wafts of mist drape themselves over the town. This is the sort of thing I’ve been waiting for. The sunlight is desperately weak but it’s enough; the mist makes the difference.

• Canon EOS-1Ds MKII, 70–200mm lens

The village of Preci in the morning mist with Monti Sibillini National Park beyond, Umbria, Italy

It is a rare bonus when the view from the accommodation turns out to be a peach of a location, but so it was here on a farm in Umbria. The morning after our arrival I’m out at dawn, looking down the valley towards the mountains of Monti Sibillini with the village of Preci perched impossibly on the hillside. Except I can’t see the village: the whole valley is shrouded in mist. It may or may not clear, but I’m set up with the digital SLR and framing the scene, just in case, as the subtle tones of dawn seep through the sky. Through a gap in the mist the village appears fleetingly, long enough for me to make a few exposures, before it disappears back into the mists. I check the image on the camera monitor: it looks OK, although very washed out, and it’s a bit flat with a lack of contrast in the scene. I know though that low contrast is a problem I can do something about later – if all the information is there on the RAW file I can optimize it in post-production. Cheating? No way, I’m just making the most of what was there at the time. It’s not as if I’m introducing any false elements; this is what I saw. Matching the tonal range of the subject to the photographic medium, be it film, paper or a digital image is what photographers have been doing since Fox Talbot’s day.

• Canon EOS-1Ds MKII, 70–200mm lens

Gondolas at San Marco with San Giorgio Maggiore beyond, Venice, Italy

Bobbing gondolas are de rigueur foreground interest for all photographs of Venice. I’m aware, standing here at San Marco looking across to San Giorgio Maggiore, that this is one of Europe’s classic views. I suspect a few other people may have taken pictures here. So if I’m going to do it, and who can seriously resist it, I have to make sure I’m stamping my own take on this timeless scene. I’ve spent several sessions on this, trying to get the combination of gondolas right with the warm sidelighting of late afternoon. I’m using just a touch of diffusion to soften the scene, combined with a hint of warming (an 81C to be precise). Generally speaking I avoid colour filtration, I always hear my first year college lecturer’s advice: ‘If you’re thinking of using a filter, don’t.’ That is overstating the case, there’s a time and place, but if used filtration has to be subtle. If its use is obvious, you’ve failed. But what’s going to make this shot is the gondolas: how much movement to use, and their alignment. Gondoliers keep coming and going, but just as the light is at its best I make this arrangement with one just coming into berth. A half-second exposure gives the desired amount of blur.

• Fuji GX617, 105mm lens

Lone figure on the dunes, Namib Desert, Namibia

Yes, it’s my supermodel, Wendy, treading boldly again. In the early days I travelled mostly solo, it was the only option, but there was no way we could have carried on that way indefinitely. And so Wendy started coming on more and more trips. Now we make quite a team. Having someone to share the driving, help establish camps and carry kit, watch my back and crucially keep me sane makes a huge difference. Sharing the highs and lows makes travel a much more enjoyable venture. She can magic a meal out of nothing while camping in the snow in Patagonia, is a nurse by trade, and has evolved over a thousand uses for a sarong. Being a photographer’s partner is not easy: there’s the interminable waiting for the light on drafty hilltops when normal people are sitting down to dinner, and dealing with a monosyllabic photographer who’s suicidal because he hasn’t made a picture in five days. She thinks it’s entirely reasonable that all her hand luggage allocation is taken up with photographic gear when flying. And, of course, she continues to be the lone figure in the landscape.

• Nikon F5, 80–200mm lens

Swayambhunath Temple, Kathmandu, Nepal

The best shots always come from planning. I’d pre-visualized this image after our first visit in the heat of the day. Now it’s just a case of spending a long hour craning upward, waiting for the pigeons to fly in the right spot on a late afternoon at Swayambhunath Temple. They’re fluttering everywhere but where I want them. I keep stamping and clapping, trying to get them to simultaneously burst forth. There are monkeys scampering over the roof of the temple, eyeing me up suspiciously. I guess they’ve seen it all before. My neck and arms are feeling the strain of peering up through the camera. I think wistfully of my first SLR, a delightfully compact and light Olympus. Modern pro cameras have certainly put on weight: is that progress?

• Nikon F5, 17–35mm lens

Angkor Wat, Cambodia

There comes a time on every trip when I question what on earth I’m doing here. At 2am I’m lying sleepless and sweaty in a windowless prison cell of a room in Siem Riep, swatting mosquitoes, jet lagged and with churning bowels. All trips have their low points when all I want to do is head for home, and this is one them. All solo travellers will know the mental roller-coaster of this game, moments of near despair followed by peaks of exhilaration. Fortunately I’ve been through so many such low points now that I know they’re transitory. And so it is here. The next day I’m exposing the warm evening tropical light of Southeast Asia bathing the ancient temples of Angkor Wat.

• Fuji GX617, 180mm lens

Tea plantation, Matale region, Central Highlands, near Kandy, Sri Lanka

Elvis is our taxi driver. He’s explaining his take on some aspects of his Buddhist faith as he drives us at some speed up into the hills. Apparently it doesn’t matter what we do, our fates are preordained, so how he drives around this blind corner is of no consequence because of our karma. And anyway, we’re all going to be reincarnated. I’m struggling to assimilate this view on life as we hurtle over another brow, dodging cattle, small children and cyclists. But clearly it was our karma to reach this tea estate high in the hills of central Sri Lanka, as I’m now looking out over this verdant green scene. It’s as if the landscape is coated in velvet: look closer and they’re tea plants, and in amongst them are women with baskets on their backs, picking the leaves. The light’s dropping and I’m busy with the camera. A well-presented man approaches and I inwardly brace for trouble, too many brushes with the Tripod Police have left me wary, but no, he’s the manager of the estate come to offer me a cup of tea. Later we sit on our veranda, watching the dusk settle over the receding planes of the hills to the north, sensing the heartbeat of Asia. Sri Lanka gets under your skin, given half a chance.

• Fuji GX617, 105mm lens

Women in a paddy field, Ben Tre Province, Mekong Delta, Vietnam

Vietnam. Just the name gives me a buzz. It’s always been a must see destination for me, and I’ve not been disappointed. I’m in the Mekong Delta, about 60 miles south of Ho Chi Minh City (Saigon). It’s a region of rice paddies bisected by a bewildering network of tributaries, flat as a pancake, and is pretty much untouched by the outside world. I’m in seventh heaven, and staying in the Communist Party hostel in Ben Tre, which has a slightly different atmosphere to a Best Western; pictures of Ho Chi Minh abound. I also have an entourage: my efforts to rent a car resulted in a driver and interpreter being thrown in. We’re all crammed into a tiny Peugeot dating from the French colonial era. I just can’t believe how green the rice paddies are. I shoot this image of women picking rice as my merry band sits in a farmer’s hut sipping Mekong whisky (only marginally preferable to lighter fluid). I’m standing with the muddy water trickling over the tops of my boots clutching the camera and 70–200mm zoom, trying to coax the ladies to raise their heads. It’s a strange way to earn a living.

• Nikon F5, 80–200mm lens

Kho Phi Phi, Tiland

I’m standing on the beach at 10.30am, the time the Big Wave struck, wondering what I’d do in the circumstances. Where do you go? Rush for high ground? There are some low hills about a mile inland, I guess at full pelt I could get there in about 15 minutes. Would it have been enough? I had to return here post-Tsunami. So many of my choicest travel moments have come around the edge of this normally balmy ocean, in countless beachside bars and bungalows in Sri Lanka, India, the Maldives, the Seychelles, Malaysia and of course Thailand. It’s where I cut my teeth as a travel photographer.

• Fuji GX617, 90mm lens

Stilt fisherman near Unawatuna, Sri Lanka

The tripod legs are slowly sinking into the soft sand. The surf is lapping around them – it’s not the most stable of supports right now. I’m not sure this is going to work, but I have to give it a go. I need the tripod because I’m using a slow exposure to accentuate the movement of the surf breaking behind the fisherman. I’ve got the 300mm lens bolted on, which is a difficult lens to keep still at the best of times, let alone when the Indian Ocean is breaking around my knees. The sun is setting into the haze in a big fiery ball; it’s Sri Lanka at its most intoxicating. This community was devastated by the Tsunami; I often wonder what happened to these fishermen.

• Nikon F5, 300mm lens

Eroded coastline of Port Campbell National Park, Great Ocean Road, Victoria, Australia

The Great Circle route between the Cape of Good Hope and Port Phillip takes you way down south, into the Roaring Forties and beyond. All the way a solitary albatross followed us, skimming the waves with apparently effortless ease. The first landfall in two weeks registered as a faint line on the radar, the coast of Victoria’s Port Campbell National Park. It’s a sight littered with shipwrecks from the days of sail, when trying to find the safety of Port Phillip was like trying to thread a needle in the dark. Now I’m gazing out to sea from that very coast, waiting for the dawn light. I used to spend hours watching that albatross from the poop deck, contemplating the moods of these angry seas. This morning it’s more benign, there’s a gentle swell lapping the beach and the light is gradually seeping through the sky giving a diffuse dash of twilight to the stacks and cliffs. It’s a unique stretch of coast here, like none I’ve ever seen. I make my exposures in the light just before sunrise, shivering in the unaccustomed chill. It’s mid-summer in Australia but here, now, you can sense Antarctica far over the southern horizon.

• Fuji GX617, 90mm lens

Uluru (Ayers Rock), Northern Territory, Australia

It may be tempting leafing through this book to think a photographer’s life is one dramatic vista after another. It isn’t. It’s often days, even weeks, of waiting, travelling and boredom, interspersed with occasional and very brief bursts of creativity. We’d driven down the Stuart Highway from Darwin, arriving in Alice Springs after weeks of outback camping, ready for a brief pit stop for rest and replenishment. And then the heavens opened. It rained for days, and days, and days. All roads out of Alice Springs were closed, and Lake Eyre started to fill for the first time in a century. The locals told us how lucky we were to see these rare conditions, but looking at the grey skies and mud we struggled to see it that way. Ten days later we were still there, marooned in a motel room watching the weather reports, wandering around the shopping centre, rapidly exhausting the attractions of Alice Springs. We had planned to head on to Uluru, but the meter on this trip was ticking and we were getting nowhere. Eventually we managed to get a flight out to Queensland, and an opportunity to regain the momentum on the stalled trip. Later we extended the journey and came back to Uluru to conclude our unfinished business. After all the rains the desert around the giant monolith was a sea of fresh verdant green growth, and then we appreciated our luck. Combined with that searingly crisp outback light at dawn it was a magical sight, worth the wait.

• Fuji GX617, 105mm lens

Oponohu Bay, Moorea, French Polynesia

A tropical paradise is a popular dream that’s difficult to find in reality. I’m wading along the shoreline of Oponohu Bay in the first light of day, up to my hips in warm water, multi-coloured fish flitting around my knees. I’m not too keen on the idea of stumbling on the submerged rocks, as I’ve got the bag on my back and the tripod on my shoulder. I’ve got no choice though; this is the only way to get to my chosen spot, found after several days of scrambling through the dense growth and wading along this shore. Location searching has, as usual, been the key, I knew the shot I was after but finding it proved difficult. After several fruitless days on Moorea I was starting to get twitchy, here I was on an idyllic South Pacific island unable to make a decent picture. Self doubt started to creep in, maybe I’d lost it, or maybe I never had it in the first place … Now though I’m happy, I know this is a good location, all I need is the light, which hopefully should be a bit more predictable than in Snowdonia at this time of year.

• Fuji GX617, 105mm lens

Perito Moreno Glacier, Patagonia, Argentina

We slipped into Argentina from Chile by the back door, driving down a farmer’s track to a border post where a bored soldier unlocked the gate to let us in, not before stamping reams of paperwork. It must be said the driving here hasn’t been a highlight; long, lurching journeys down dusty boulder-strewn roads, wondering if our rental sedan will make it as yet another rock gouges a piece out of the undercarriage. We arrived in El Calafate feeling like the marrow had been shaken out of our bones and our internal organs re-arranged. Next item on the agenda of our South American odyssey is Perito Moreno Glacier, a massive river of ice tumbling down from the Patagonian ice cap, the largest outside of the Polar Regions, and a truly jaw-dropping sight. Hopefully now this two-month adventure will start to develop some momentum. It’s weird, sometimes on these long trips a week can go by without a camera being touched due to a combination of travelling days and indifferent weather. How can that be? I get decidedly twitchy until the next decent image is exposed. One of the toughest challenges on the road can be maintaining a positive attitude when things are not going well, particularly when travelling solo.

• Fuji GX617, 90mm lens

Solitary figure in the Valle de la Luna at dawn, Atacama Desert, Chile

The Atacama Desert is the driest place on earth – a rippling lunar landscape of rock and saltpans. It’s dawn and Wendy is treading boldly up a rocky ridge, providing perspective again. I’m on a ledge above, looking down on her dwarfed by the harsh folds of the Atacama, stretching to the volcanic peaks of the Andes that dominate the horizon to the east. In the midday sun it’s about as harsh a place as you can imagine, but in the soft light of dawn the elemental shapes and textures of the desert are simply beautiful and inspiring. Top of my agenda at this moment is a battle with a disintegrating cable release. An accessory costing next to nothing is on its last legs and I have no replacement – something of an oversight. On long trips I try to carry spares of the bits and pieces that are so important: filter rings and holders, grads, quick release plates etc., but weight is always an issue and tough choices have to be made. The sun pops over the horizon and I make the shot. I’m getting a bit casual about the light – it’s so predictable. Every day it’s sunny from dawn to dusk, and clouds are just a memory. It must be said the light doesn’t have the subtlety of an October day on the Isle of Skye, but still the luxury of dependable rays every day is a relief.

• Fuji GX617, 180mm lens

The road to Marras at dawn, Pampasmojo, near Cusco, Peru

The sun is slowly punching holes in clouds. Just as the light is beginning to lift the landscape in the foreground, a farmer drives his donkeys down the road, winding their way into frame with the Andes towering above. I use a 0.9 ND graduated filter to hold back the sky and with +0.3 exposure compensation dialled in I expose a few frames, revolve the camera and make a vertical composition. Is there such a thing as a lucky shot? Well, the donkeys appearing at the right time was a stroke of luck, no question. But I’ve been here on duty by the tripod in the perfect spot at the right time of day for two mornings now and that was no accident. As they say, you make your own luck. Photography is all about putting yourself in the sort of situations where you can make the most of Lady Luck when she does come along.

• Canon EOS-1Ds MKII, 70–200mm lens

The Kootenay River and Rockies, Kootenay National Park, British Columbia, Canada

It’s the last night of the trip, a two-month adventure wandering through Alberta and British Columbia. Tomorrow we catch a flight home from Calgary, so we’re enjoying our last night of camping in the boonies, cooking over a fire with just the river and Rockies as a backdrop. I love this country, with its huge landscapes, easy people and sense of space. I’ve knocked off from duty after two months of dawn and dusk shifts, and we’re just enjoying being here, but the last light on the mountains is gorgeous. Maybe I’ll just see what I can make of this. I move to within just a few feet of where we’re camping and find a verdant clump of wild flowers to use as foreground interest. The rushing glacial waters of the river are a light sky blue, and the last light of day is just catching the peaks. The huge contrast range between the sunlit Rockies and the foreground calls for some creative use of neutral density grads and a polarizer to balance it all. I make the exposures and wander back to camp, mentally dismissing the image I’ve just made. It may not have worked, if it does it’s a bonus, but unlikely to rival some of the epic vistas we’ve had on this trip. It turns out to be the best shot of the trip by far.

• Fuji GX617, 105mm lens