Real-World Adaptive Level Design

Today, I look forward and I see a future in which games once again are explicitly designed to improve quality of life, to prevent suffering, and to create real, widespread happiness.

—JANE MCGONIGAL, REALITY IS BROKEN1

We are called to be architects of the future, not its victims.

—BUCKMINSTER FULLER, FROM A FULLER VIEW2

THIS BOOK HAS INVESTIGATED games and architecture as two separate entities that, while similar and having a lot to teach one another, are isolated by the boundary between game and real-world realities. Games find themselves apart from reality in tightly defined rule-based universes abstracted from the complexity of real life. And real life is more serious than “just games,” right?

There have, in fact, been games developed for the purpose of affecting elements of the real world by modeling scenarios in ways that let players explore them, learn about them, or use game mechanics to overcome them. The term for these explorations is persuasive games, games that affect the world around them in some way. Both high-and low-tech game solutions have been created that add game elements to the real world in ways that make our everyday lives important to in-game activities and vice versa. These are pervasive, augmented, and alternate reality games that turn real-world architecture into gamespace.

In this chapter we tear down the barrier between real and gamespace to discover how the rules of games can create new possibilities for real-world space. We consider the purpose of putting such games into real-life spaces, and what positive effect social games have on the spaces in which they are played. We also look at how models for urban interaction can give us insight into how these games can be designed to best facilitate player socialization in real space.

What you will learn in this chapter:

When magic circles collide

Adaptive game reuse goals

Analysis for adaptive core mechanics

There exists in game design theory a concept of a separate reality created by games wherein the rules of a game are laws by whichh that the inhabitants, players, must abide. Entering this world requires only that players recognize the rules and agree to abide by them as long as they are inside. This concept is known as the magic circle, a term borrowed from Johan Huizinga’s Homo Ludens3 and used to describe the temporary worlds created by games4 (Figure 11.1).

Magic Circles Colliding through History

We have previously discussed ways in which games address the world around them through metacommunication—the ability of games and media to highlight things about the world around them or create abstract simulations of real actions. We have seen this in games such as spin the bottle, where players play at kissing one another without the condition that they are in love, and online first-person shooters allow players to shoot one another with guns, but there is no real-life murder involved.

FIGURE 11.1 A popular graphic for expressing the magic circle is that of a game of marbles. Players shoot other marbles to knock them out of the game boundaries.

For centuries, games have been used to model real-world behaviors in similar ways, but for uses that extend beyond the playing of games for entertainment purposes. In ancient China, the game Weiqi, which we know today as Go, was one of the four accomplishments used to qualify men for service in the bureaucracy, along with painting, poetry, and music.5 Chaturanga, which eventually evolved into what we know today as chess, was a simulation of Indian military strategy based on four divisions.6 Miniature wargaming originated in 1824 when a Prussian prince utilized a miniatures game created by his father to teach military tactics to other officers.7 In 1929, Edwin Link Jr. invented the Link Trainer, the first flight simulator. This device, originally developed as a carnival ride, would become instrumental in training U.S. Air Force pilots during World War II. This led the way to more video game-like machines with movable cameras and model landscapes.8 In the 1960s architect and philosopher Buckminster Fuller created the World Game, a series of logical challenges in which groups of players would address world crises.9 These games are a few historic examples of how games have been used to create real-world effects. Today, the games discussed would be called serious games, since they model real-world scenarios in such a way that they train players to deal with them.

Beyond serious games, there are games that utilize both high- and low-tech to merge their magic circles with the real world. These games do so by changing the context in which the games are encountered. Rather than engaging stationary devices like PCs or television consoles, these games utilize mobile devices, augmented reality displays, and portable pieces like playing cards to administer gameplay. This allows them to transform real-world spaces into gamespace. Thus the mechanics of these games can take on real-world contextualization.

An early example, The Beast,10 was an advertising game created by Microsoft as promotional material for the film A.I. Artificial Intelligence.11 In this game, players could receive e-mails or phone calls, read blogs, or go to websites with information relevant to the movie’s fictional world. This material also had relevance to actions players could take in the game. However, the delivery of in-game information through the user’s real-world communication channels or regular Internet browsing made it contextually unique. Games like Shadowcities12 or Ingress,13 where users’ mobile phones are the medium through which the game is played, require players to move through real urban spaces to locate and capture in-game items. During the play of either example, the technology is merely a tool that feeds information to players on how they should move through real-world gamespace.

Such games take devices on which users would otherwise be playing games and make them the facilitators of players’ real-world actions by giving them in-game contexts. The Dark Knight ARG,14 a game used to promote the Batman film The Dark Knight,15 sent directions to public game events via websites or e-mail. The computer therefore became a facilitator for game experiences. Likewise, Ingress challenges players to use their global positioning system (GPS)-enabled smartphones to find portals in real-world cities. These portals are only visible within the Ingress Android application, and the player must be close to them to interact. This requires players to use their phone to influence their real-world movements for the game.

An important element of these games is that the medium with which the game is played—computer/Internet, smartphone app, text message, or deck of cards—is an administrator of in-game actions. Even when a human game master is acting from afar and sending content to players, the user end experience is one of interaction with his or her device. For this reason we can say these games have a major component of device as Dungeon Master, where real-world gameplay is facilitated by some technological or analog method.

In modern iterations of these games, the medium for game administration is often portable, allowing players to move independently. Before smartphones were as popular as they are today, some games, such as Frank Lantz’s Pac-Manhattan16—a version of Pac-Man17 played around Washington Square Park in New York City—utilized cellular telephones to connect players to “controllers.” These administrators would give players game and location information that is managed by smartphones today. Also, cameras on these devices, portable game consoles like the Nintendo 3DS, and Google Glass allow for the overlaying of augmented reality (AR) information. AR is the implementation of digital information to enhance the real world. A simple example is the graphics overlaid onto televised American football games. Viewers can see the line of scrimmage or the line the ball needs to cross in order for the offensive team to earn a first down.

Depending on the context and delivery medium for these games, they can be divided into several categories. These will be useful to us later, as we define how these types of games can be utilized to inform game reuses of urban space.

We can divide magic circle games into the following categories.

Pervasive games utilize a mobile device or mobile device feature of some sort (smartphone, text message, application, GPS, etc.) to administrate physical gameplay in the real world. This most often includes, but is not limited to, movement through real-world spaces.

Augmented reality games specifically utilize digital information overlaid onto views of the real world. This can involve finding objects in real spaces by viewing them through the camera of a mobile or other AR-capable device, or simply using the real world as a backdrop for a digital game (Figure 11.2).

Alternate reality games use delivery vectors that players use in their everyday lives—e-mail, phone, text message, etc.—to send players in-game directions or information without acknowledgment that the message is for a game. Examples include receiving e-mails from in-game characters as though you were one of their colleagues. These may or may not involve needing to travel around real-world space.

Low-tech public games utilize a commonly agreed upon ruleset, scenario, or a low-tech portable game piece such as game cards to administer in-game actions. Examples include live-action role-playing (LARP) games such as historic reenactments, fantasy role-plays, and immersive improvisational theater scenarios. More game-like examples include Humans vs. Zombies,18 a “big game” played on college campuses where human players cooperate to fend off teams of zombie players over varied periods of time: hours, days, or months. There is also Metagame,19 a social card game of debating about art, culture, and video games for play at parties or game conferences.

FIGURE 11.2 Augmented reality games utilize mobile devices as a window through which players can view in-game action. This can have uses either in administering digital explorations of real-world space, or as a visual gimmick.

By understanding these types of games and how they administer real-world play, we can also see how they may be adapted to directly address real-world spaces. We can begin to see how designers may use them to facilitate interaction between players. In the next section, we will take a look at how these games can be utilized for architectural reuses and what the goals of such implementations are.

Combining games with architectural space offers opportunities for different types of gameplay experiences in the real world. To understand how these experiences occur, we must understand the goals of adaptive game reuse—using game mechanics to transform the experience of real-world spaces.

From Chapter 2, “Tools and Techniques for Level Design,” we know that a major goal of level design is the augmentation of space. In adaptive game reuse, space is augmented figuratively with game mechanics and sometimes quite literally through augmented reality devices. We can accomplish the other level design goals by adjusting their meaning for real-world contexts. “Adjusting behavior” describes how the insertion of game mechanics into real-world interactions can give actions gamespace-important meanings. It also describes how a player’s motivation for performing real-world actions can transform into performing ones dependent on in-game incentives. “Transmission of meaning” can describe how narrative descriptors delivered by game devices can change the meaning of actions (“I’m going downtown to find a portal”). It can also describe how game mechanics in real-world space can affect positive change in the space, or even facilitate players toward art or structures that themselves have important meaning.

In addition to adapted versions of our goals for level design, real-world games can and should also have their own set of design goals. Unlike video games, real-world games are inserted retroactively into preconstructed spaces. This is the opposite of our video game level design methods, in which we designed game levels to complement game mechanics. In this instance, we are designing game mechanics to complement level space. This is why we concentrate on this type of level design as adaptive game reuse.

Adaptive game reuse games are meant to highlight a condition of their preexisting level spaces. They may also facilitate some type of action within these spaces. We may even use a combination of these properties to affect positive change within the space. Thus we can say that there are three goals for adaptive game reuse. They are the building of:

1. Games that enhance

2. Games that pervade

3. Games that rehabilitate

These goals give us a lens through which we can study previously designed adaptive reuse games and see how they might inform our own designs.

The first goal for adaptive game reuse games is enhancement of the space that already exists. Games that accomplish this take some themeing or mechanics from their site and use the game to highlight these features. Games that enhance are great enactors of the level design goal of transmitting meaning. For example, a powerful tool for storytelling in gamespaces, as we have discussed previously, is embedded environmental narrative—textures, 3D models, and other art assets with narrative purposes. Games can be utilized in real-world gamespace to direct players toward similar meaningful pieces: architectural details, works of art, or museum exhibits.

The Smithsonian American Art Museum utilized such a game during its Art of Video Games exhibit in 2012. Taking advantage of the increased number of visitors from the game exhibition, it had D.C.-area game designers create a scavenger hunt game called Museum Quest. Players would hunt down museum “ghosts,” played by exhibit volunteers, and beat them in dice games. This facilitated movement through the museum’s many exhibits for visitors who may have otherwise only visited the Art of Video Games.

The Virtual Public Art Project,20 an app for displaying public virtual art, utilizes augmented reality and GPS technology to overlay 3D modeled sculpture onto public spaces (Figure 11.3). Augmented reality is also utilized on the Nintendo 3DS in the AR Games21 application to add game images to real-world environments. Players place cards with specific images onto a flat surface, which will be recognized by the app, causing game data to be displayed. For example, some games turn whatever surfaces the player is aiming the camera at into a fishing pond or archery range. Dragons or other creatures may attack, causing players to move themselves around the table to avoid losing the game. The app also has a function for adding customized Mii characters to images. Creative players have reproduced the card images on large-scale formats to create giant Miis in real-world public spaces, and then spread the images over the Internet. Applications like this demonstrate how games or game-like applications can encourage participation through game incentives or creative tools.

FIGURE 11.3 The Virtual Public Art Project app enhances public spaces and encourages visitation by displaying 3D modeled sculptures in specific locations that can only be accessed by viewing them through smartphones.

The next type of adaptive game reuse game builds upon the previous goal’s focus of enhancing specific spatial experiences with games and utilizes them as tools for enhancing parts of everyday life. These games pervade our ordinary experiences in such a way that they enliven otherwise mundane activities like commutes and turn them into gameplay opportunities. They also facilitate social interactions between players of these games through shared experience of the mechanics and opportunities for emergent encounters.

While not one specific game, but a feature of a portable console, the StreetPass function of the Nintendo 3DS provides a pervasive game experience. It allows two passing 3DS devices to interact and exchange a small amount of data—game stats, race times, characters, or other things depending on the games each player uses—that can be played within each other’s games. Nintendo’s own accompanying games for this feature require interaction with many other 3DS owners to complete, so social play is encouraged.

StreetPass turns travel through populated areas into a game through passive means. While users do not have to be constantly engaged with it, the feature can be active while they go about their daily routine. This encourages users to keep the system with them and play with the data they receive from other players at their convenience. The mechanics of each game have inspired groups of users throughout the world to form the StreetPass Network, which arranges gatherings in cities so players can not only gain lots of StreetPasses but also reap the in-game benefits of repeat encounters. By combining features that encourage user interaction and repeated use in the outside world, StreetPass enhances players’ everyday routine with passive play.

Games like Shadowcities and Ingress pervade the user’s everyday experiences. These games have players competing for territories with other factions. Territories are captured by attacking specific landmarks, which must be in the immediate vicinity of the players attacking them. Many of these are located at real-world destination landmarks, such as statues, museums, or other important structures. Since it is developed by a subsidiary of Google, Ingress integrates many of Google’s social features, such as Google+, into its gameplay. This turns the game into a simultaneous augmented-alternate reality pervasive game. By being dependent on location, these games can also become a part of a player’s everyday routine or further enhance visiting new or faraway places.

The third goal for adaptive game reuse games is spatial or personal rehabilitation. These games utilize magic circle games’ ability to both enhance an element of a space and influence the actions of players, and use these abilities to effect positive change.

Both games and architecture have been proposed as interventions for various societal problems. To educate people about alternative ways to address world problems, Buckminster Fuller created the World Game. Likewise, architects have addressed the lack of affordable housing and the need for environmental sustainability with projects such as Cotney Croft and Peartree Way in Stevenage, Hertfortshire, England, by Bailey Garner LLP22 (Figure 11.4).

Game designer Jane McGonigal merges the two in many of her real-world games, which focus on the needs of a specific location or community and determine how a game might be beneficial. In Cruel 2 B Kind, for example, players are texted an act of kindness that is their weapon and one that is their weakness but are given no information on who else is playing the game. They are supposed to wander around a public space defined as the game boundary and perform their random act of kindness/weapon to others without calling attention to themselves or indicating that they are playing a game. Players are eliminated if they are the recipient of the act of kindness which is their weakness from another player, but must themselves be kind to as many people as possible to find their target. In her book Reality Is Broken, McGonigal explains that she designed this game to increase the jen ratio—the amount of social well-being in a space—of wherever it’s played, as it reinforces kind behavior, even if only for the length of the game (Figure 11.5).23

FIGURE 11.4 Affordable and environmentally sustainable developments like those at Cotney Croft and Peartree Way in Stevenage, Hertfortshire, England—completed by Bailey Garner LLP in 2011—address larger issues through their construction methods.

FIGURE 11.5 Cruel 2 B Kind players utilize acts of kindness to hunt for one another within a defined public area. As a side effect, non-players benefit from their gameplay actions.

McGonigal’s game Tombstone Hold-Em addresses the problem of cemetery care and maintenance caused by lack of visitors through a variant on a popular card game. Players divide into pairs, and after three cards of a five-card hand are drawn, must find tombstones that will complete a winning poker hand. The shape of a stone determines what suit (hearts, diamonds, clubs, and spades) it is, and the dates on the stone determine the card value. To use the stones as cards, the players must be able to touch the tombstones, but also some part of one another. A beneficial side effect of this game is that since players must be able to read stones to utilize them, they often have to clean them off or move debris away from them.24

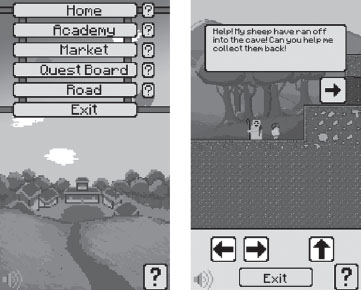

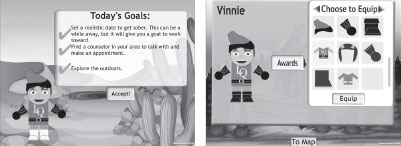

In addition to these low-tech variations, rehabilitating games can use digital delivery vectors. Two games designed at George Mason University, Onward25 and Life Quest,26 utilize common game mechanics and themes to motivate people on criminal probation through that difficult process. Each app utilizes a check-in system to track player tasks but contextualizes real-world activities in different ways. Onward allows players to define their own quests, which respond to their own goals for bettering their lives—education, distancing themselves from dangerous influences, overcoming drugs, etc. As players progress through the quests, they are given points that can be spent in the game’s store for items, which can then be utilized to progress through in-game adventure levels (Figure 11.6). Life Quest, on the other hand, has players choose their own quests at the beginning of play, and then moves them along a board that asks them to check in on their quest progress. For completing quests over certain intervals, players are given in-game rewards that can be used to customize their avatar (Figure 11.7).

These games create positive intervention because of designers’ investigations into the problems they are trying to correct or the space they are trying to rehabilitate. By combining game mechanics with goals for creating real-world effects, architectural spaces can become socially transformative gamespaces. Creating these kinds of effects requires users to understand both the problems they are trying to address and the space in which they are putting their games.

FIGURE 11.6 Onward gives players in-game currency for completing out-of-game quests toward finishing the probation process. This allows players to progress in in-game adventures.

FIGURE 11.7 Life Quest tracks player progress in real-world quests with an on-screen game board, and then rewards them with in-game items.

In the next section, we explore analysis methods for finding the mechanics of real-world spaces.

ANALYSIS FOR ADAPTIVE CORE MECHANICS

Now that we know what the various goals for adaptive game reuse are, we can explore how to plan for their gameplay. We have just discussed how real-world games differ from video games in terms of when their levels are constructed. As real-world spaces, adaptive reuse games’ levels are often built before the game that will be designed for them. This is counterintuitive with how levels are designed for games—in response to the game’s intended mechanics. The question is how to find the core mechanics of public gamespace.

Video game level design follows the mantra “form follows core mechanics.” However, explorations of pervasive games by Jane McGonigal, the Smithsonian, Local No. 12, and others show us that like many multiplayer games, the mechanics of these games are derived from the intended social experience. Cruel 2 B Kind encourages emergent pleasant interactions between players and visitors, Museum Quest seeks to increase user engagement in museum exhibits, and Metagame facilitates socialization at game conferences.

In addition to focusing on social user experiences, these games derive their mechanics from the architectural use or social condition of the intended playspace in which they intervene. In this way, it is easy to discern the core mechanics of spaces. For example, Museum Quest seeks to expand the area of the museum that the players will explore and the number of artworks they will see. Thus exploration is the core mechanic of this game, as it is designed to support an exploration and observation space. As tracking systems, Life Quest and Onward transform the concept of a to-do list into gameplay. Depending on the issues players have that led them to be on probation, these games turn self-improvement tasks, such as signing up for a GED program or building a resume, into quest mechanics.

As we have seen, many of these games are designed to facilitate user engagement in sites: museums, public spaces, commuter spaces, etc. This focus on public space allows us to revisit the urban design principles of Modernists and of New Urbanists to explore how the game mechanics of these projects build social gameplay.

In many ways, the danger of “always there” technology such as mobile phones is their ability to connect everyone to their personal social network at all times. While this may seem counterintuitive to our discussions about network capabilities as facilitators of play, the danger of these devices is their ability to put everyone on their own social desert island. Self-contained mobile applications that keep players’ attention too focused on the app itself risk becoming the Ville Contemporaine of the tech world. For many games, and for the level design concepts discussed, this is fine. However, adaptive game reuse games seek to create public social game experiences.

We have previously discussed Jane Jacobs and her ideas on developing neighborhoods with mixed-use buildings that allowed people to cross paths and interact. We also discussed how multiplayer games could utilize spaces appropriate for different types of play styles in one level to create rich, emergent spaces. This is also true for games meant for public spaces. On the one hand, there can be private gameplay stages, such as the adventure levels in Onward or the mini-games in the 3DS’s StreetPass software, that are private to the owner of the device. However, these games also have a public aspect. Onward utilizes points gathered in real-world interactions to impact these private game experiences. StreetPass utilizes wireless communication between devices to exchange resources required for its packaged games—puzzle pieces, characters, game data, etc. Alternating public-private gameplay encourages social gatherings for these games, as the gatherings become an important element of gameplay. If one were to map gameplay of these pervasive games, one might find that it resembles an occupant of the type of neighborhood Jane Jacobs advocated for: players stay primarily in their private spaces, but move outward to interact with others on sidewalks or in social nodes (Figure 11.8). In this way, the private modes of these games—role-playing games (RPGs), resource managing, collecting, or exploration—become a quest hub for the player’s real venturing into public social play scenarios.

FIGURE 11.8 Games such as StreetPass facilitate movement through real public space by alternating public and private modes. Modes such as mini-games or resource management/collecting can be enjoyed privately, while collecting these resources requires gathering in public areas.

These games also benefit from the existence of public characters. We have already seen how fostering regular interaction between players can enhance multiplayer game experiences. Public games can benefit from game structures or social groups in which gameplay is facilitated by a leader. In this chapter we have stated that these games use the device as the game’s Dungeon Master, but there is also room for human administration for organizing gameplay events, tournaments, or parties. For example, the StreetPass Network is administrated by Josh Lynsen, who began the network in Washington, D.C., after seeing Japanese gaming fan groups gather to use the social features of Dragon Quest IX.27 While StreetPass as an application allows for interaction between random players, Lynsen’s organizing of like-minded players has fostered a much more formal movement of interactive social play. For example, players of the StreetPass game Find Mii,28 an RPG where the Miis of StreetPassed players are recruited to fight monsters, can arrange to help one another via repeated uses of one another’s Miis, having their Miis wear certain colors for rooms that require them, or exchange gameplay tips. As a side effect, this community has developed a shared understanding of StreetPass-enabled games. This is another element of constructivist learning. In addition to trial-and-error engagement in gameplay, constructivism includes the building of shared knowledge by multiple users. This is social constructivism, and can greatly enhance how people play and learn about games.

Such groups allow for engagement with non-players in ways that can have a positive effect on the public gamespace. As we saw with Cruel 2 B Kind, players’ “killing with kindness” was meant to affect non-players and enhance the overall jen ratio of the gamespace. StreetPass groups in major cities are a readily available social circle that out-of-town visitors or people who are new residents in a city can take advantage of. Lynsen has reported that tourists who are also StreetPass users have approached his group during D.C. events. By building games with public characters, along with mixed-use public-private mechanics and site-specific core mechanics, we can generate positive effects for public urban spaces with games.

In this chapter, we moved outward from video games and into games that create real-world play opportunities. We learned about the magic circle, a concept for describing how games create their own nested realities. We studied games that blur the boundaries of these magic circles—pervasive, augmented, alternate reality, and low-tech public games—and discussed the types of technology used to bring games to the real world. These games utilize devices as Dungeon Masters and allow users to move independently through the real world with game accompaniment.

We looked beyond classifications for these games to discover gameplay goals that can help us bring gamespace to the real world in adaptive game reuse games. These games can allow us to intervene in troubled public spaces or communities with play. These goals for creating games that enhance, games that pervade, and games that rehabilitate utilize technology or game tools to turn users’ interactions with real space into gameplay. If modeled properly, these games can have great positive effects on the public spaces in which they are played.

Finally, we discovered how the structure of these games—utilizing mixed-use neighborhoods like those advocated by Jane Jacobs—can facilitate social interaction between players. On the one hand, a variety of gameplay mechanics and a mixture of public and private play modes can turn these games into self-contained quest hubs. On the other hand, public figures such as game or social group organizers further help build communities that can have positive effects by visiting public areas. Through these design methods it is possible to take what we know about level design, architecture, user engagement, and social urbanism and bring them into one shared gamespace.

1. McGonigal, Jane. Reality Is Broken: Why Games Make Us Better and How They Can Change the World. New York: Penguin Press, 2011.

2. Sieden, Lloyd Steven. A Fuller View: Buckminster Fuller’s Vision of Hope and Abundance for All. Studio City, CA: Divine Arts, 2012.

3. Huizinga, Johan. Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play-Element in Culture. Boston: Beacon Press, 1971.

4. Salen, Katie, and Eric Zimmerman. Rules of Play: Game Design Fundamentals. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2003, pp. 95–96.

5. Pinckard, William. Go and the “Three Games.” Kiseido’s home page. http://www.kiseido.com/three.htm (accessed August 8, 2013).

6. Bird, H.E. Chess History and Reminiscences. London: Dean & Son, 1893. http://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/4902/pg4902.html.

7. History of Wargaming. HMGS. http://www.hmgs.org/history.htm (accessed August 4, 2013).

8. Donovan, Tristan. Replay: The History of Video Games. East Sussex, England: Yellow Ant, 2010, p. 59.

9. World Game. Buckminster Fuller Institute. http://www.bfi.org/about-bucky/buckys-big-ideas/world-game (accessed August 8, 2013).

10. The Beast. Microsoft (developer and publisher), 2001. Alternate reality game.

11. A.I. Artificial Intelligence. DVD. Directed by Steven Spielberg. Warner Bros., 2001.

12. Shadowcities. Grey Area (developer and publisher), 2011. Mobile phone MMORPG.

13. Ingress. Niantic Labs (developer and publisher), 2012. Mobile phone MMORPG.

14. The Dark Knight ARG. 42 Entertainment (developer and publisher), 2008. Alternate reality game.

15. The Dark Knight. DVD. Directed by Christopher Nolan. Burbank, CA: Warner Bros. Entertainment, 2008.

16. Pac-Manhattan. Tisch School of the Arts, New York University (developer and publisher), 2004. Real-world pervasive game.

17. Pac-Man. Namco (developer and publisher), 1981. Arcade game.

18. Humans vs. Zombies. Gnarwhal Studios (developer and publisher), 2005. Real-world “big game.”

19. Metagame. Local No. 12 (developer and publisher), 2011. Social card game.

20. Virtual Public Art Project. Virtual Public Art Project (developer and publisher), 2010. Augmented reality mobile application.

21. AR Games. Nintendo (developer and publisher), March 27, 2011. Nintendo 3DS augmented reality game.

22. Building Futures: Cotney Croft and Peartree Way, Stevenage. hertsdirect.org Partnerships. http://www.hertslink.org/buildingfutures/content/migrated/branches/13888224/17087247/17233828/cotpear (accessed August 9, 2013).

23. McGonigal, Jane. Reality Is Broken: Why Games Make Us Better and How They Can Change the World. New York: Penguin Press, 2011, chap. 10.

24. McGonigal, Jane. Reality Is Broken: Why Games Make Us Better and How They Can Change the World. New York: Penguin Press, 2011, chap. 10.

25. Onward. Poxel games (developer), Center for Advancing Correctional Excellence (publisher), 2013. Mobile serious game.

26. Life Quest. Team Life Quest (developer), Center for Advancing Correctional Excellence (publisher), 2013. Mobile serious game.

27. Dragon Quest IX: Sentinels of the Starry Skies. Square Enix (developer), Nintendo (publisher), July 11, 2010. Nintendo DS game.

28. Find Mii. Nintendo (developer and publisher), March 27, 2011. Nintendo 3DS StreetPass game.

INTERVIEW WITH CHRIS WEED

Founder, Gnarwhal Studios

Chris Weed is co-founder of non-digital game company Gnarwhal Studios and the co-inventor of the big urban game, Humans vs. Zombies (HvZ). [NB. parentheses should be roman] Played on college campuses throughout the world, HvZ is a game of tag where zombie players must tag human players when they are walking through public areas.

Can you name a game, level, or level designer (or multiples of each) whose work has left an impression on you? Why?

This is the single hardest question to answer. I’ve grown up with video games. I’ve grown up in video games. I can still collect almost all of the heart pieces in The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past. That information is burned into my mind. I’m confident that were I to suffer severe head trauma and forget my own name I would still be able to find those heart pieces.

It’s very difficult for me to make a coherent list of any reasonable length of level design that has left an impression on me. Now that my childhood house has been demolished, the levels I played on my NES and SNES in my room are as real to me as my actual room. Maybe they’re more real to me, because I can never go back to my childhood room but I can always play through the games again.

To give an actual answer that isn’t a cop-out, this past week I’ve been playing Guild Wars 2 and I have been continually impressed by how beautiful and varied the areas are.

Are there any media outside of gaming that you find inspire your work?

I think I’m very critical of myself and my abilities to the point where I often feel lacking for inspiration. When I do find inspiration it’s important for me to accept it in whatever form it comes in. Sometimes that can be a good conversation or a cup of coffee that leads you to just want to create or do something. I take a lot of inspiration from movies and novels as well. There’s also a certain amount of inspiration you can find in the dark parts of life and the things that upset you. Working to correct those things can be very inspiring.

Describe your level design process—how do you begin? What tools do you

use (on or off the computer)?

For Humans vs. Zombies (HvZ) the process is very low-tech and almost always starts with walking through an area (or thinking about an area if you know it well enough), letting your mind wander to various thoughts of “wouldn’t it be cool if and then figuring out how to create those moments. There are a considerable amount of things you need to keep in mind in order to know which ideas are worth pursuing and how your players will interact with the space. You need to be better at poking holes in your designs than your players will be. For that reason it’s often helpful to work with other people and for one person to take on the role of saboteur.

Seeing that process take shape from a single idea to an actual event to stories the players are telling months after the game is an incredible process and one of my favorite things in the world.

What is your process for playtesting your levels?

The last question describes our process of poking holes in our own design. That is the extent of our playtesting. Due to the nature of the game, we simply can’t test our ideas. The best you can do is to learn from prior experience and try to apply those lessons to future designs.

Do you find art and atmospheric effects an important tool for communicating with players? Any specific examples?

Atmosphere is one of the most important elements of our game. With HvZ we have an unusually small amount of control over that atmosphere. The control we do have as designers is mainly to set the tone for the game. We usually make an attempt at theatrics and an overarching plot to tie all of the game’s missions together. Though, truth be told, this is almost always the first area to fall victim to triage when we are down to the wire.

The players also have a huge responsibility for the atmosphere of the game. The biggest challenge here is usually just making them aware of this. If you can make your players understand the impact their attitude and approach will have on their own experience, they will often be reasonable. There is of course a balance you need to strike, and there are certainly times when you need to step in and correct behavior. Transparency, honesty, and authority are the most important tools when doing this.

The last factor in the atmosphere for the game is the location you are playing in and also the literal atmosphere. Weather can completely change how players interact with a space. Despite our best efforts, we have not had any luck in controlling the weather.

An example of all three of these factors coming together is one of my favorite missions, the Laser Mission. The mission began at 10 p.m., two hours before the game officially started and before the original zombie could begin tagging humans. We had players meet in our campus’ chapel and sit in the pews. We introduced them to our plot, that they were among the last survivors on earth living in a small community that was now thought to be compromised. The lights went out, zombies began banging on all of the windows. Even though they knew they weren’t in any real danger, that the game hadn’t started, the players all got into it. They screamed and huddled in the middle of the building. The zombies burst through the doors and the players dispatched them. They were told that in order to turn the power back on, they needed to fix the power grid. This involved a high-power laser pointer on a tripod and several Ikea mirrors. The players had to position the mirrors so that the beam of light would hit a spot across campus.

We opened the doors and all walked out of the chapel into the most beautiful foggy night I have ever seen. Half an hour before it had been a clear boring night. We could not have asked for or planned for a more atmospheric fog. It made the mission infinitely more exciting and is to this day one of my favorite memories of the game.

How do you direct the actions of players in your levels? How do you encourage players to play in undirected ways?

Usually there is a conceit of players needing to amass themselves in a specific location before the mission can begin. From there we have several methods we use. We either give players a location they need to get to, a specific target, in which case the difficulty comes from getting to that one location, or we make the objective more vague and only give clues, in which case the difficulty comes from figuring out what or where the objective is. Alternatively, we can use a non-playing character (NPC) to lead the players in a specific route. There are pros and cons to each method mainly centered around exactly what the players will be able to make decisions about. Using an NPC and taking a specific route can allow you to lead your players in an interesting, well-designed route, but it removes some of their agency and some possibilities for meaningful choice.

There is also another method, which is to create an artificial barrier. For example, “You can’t go beyond that fence.” This is much harder to do in a real-world game and requires that everyone playing keep another piece of information in their brain. This might seem like a small trivial detail when you’re designing a mission, but in that moment when a player is experiencing your mission, every addition like this has a high cost. Making the additions intuitive and obvious goes a long way to softening the blow. It is important to remember that for every rule you add, you’re adding potentially infinite edge cases that you haven’t thought of. Without an experienced intuition for how a game works and how your players interact with it, this can be very dangerous.

What laws of level design have you developed in your own work that any designer should know? What should he or she avoid?

I was on a panel a few years ago with Nathalie Pozzi, whose background is in architecture. She explained how similar the two domains felt to her. In both you’re creating a possibility space. You direct how people will interact with what you build, but there’s a limit to how far you can control it. That has stuck with me and feels especially true with games like HvZ. When you are responsible for creating the very physics of your game, it is easy, I think, to take the control you have over that world for granted. With HvZ our control is much more withdrawn. We’re forced to accept the location we’re given and work from there. We also cannot control (no matter how much we might sometimes want to) how our players will interact with what we design. It has led to a very soft, almost improvisational approach to design. Rather than asking “what possibilities should I create?” I find myself asking “how can I prepare for the things I’m not anticipating?”

Now, with screen games, and depending on your genre, that might not sound like a lesson that applies—and it might not apply in the same way. There are, however, very important collaborative moments, particularly in the playtesting phase. My “law” then would be to have a soft understanding of what your game is until you see other people playing it. Learn from your players.

What inspired you to create a game like Humans vs. Zombies on your college campus?

HvZ was a rebellious, anti-authority, extremely silly act. We wanted to make the campus our own. We wanted to create something fun and accessible. We thought zombies were cool. To say a whole lot more about it would probably be a betrayal. There honestly wasn’t much thought about it.

To dig a little deeper, one of my high school teachers would tell us stories about month-long games of capture the flag that he would play in college. If no one was guarding your flag, people would break into your dorm and steal it. I think those stories probably had the single biggest effect on my grades. From that moment on I knew I had to get into college.

How did you originally build a community of players to play a “big game” in a real space?

We put fliers up around campus. The start of HvZ also coincided with the beginnings of Facebook. We were really into what we were doing, and I think people saw that and wanted to be a part of it. Also, a whole lot of luck.

How does the experience of playing Humans vs. Zombies transform the spaces it is played in? How does playing Humans vs. Zombies transform player actions in these public spaces?

A low wall becomes a point of ambush. A walk to a cafeteria becomes a challenge of your bravery. The shadows make you feel safe. When you are committed to the game, it changes how you see nearly everything you come in contact with. It is a very primal feeling. Leaving the safe zones immediately raises your heart rate. Your eyes become hyper-aware of sudden movement. Any sound moving toward you makes you freak out. To some people this probably sounds like a nightmare, but for a lot of people they feel more alive than life usually allows.

You cease to see the world around you as serving an aesthetic sense. The space around you is both a tool and an obstacle of your survival. To that end you feel much more connected to your surroundings. The better connected you are, the better you will be at the game. The game incentivizes that connection.

The spaces change after the game is over as well. There are non-descript areas of campus that now hold very special meaning to a lot of people. While it’s obviously just a silly game, the kinds of shared experiences it creates really can transform spaces forever. One example is a small courtyard on campus where nearly fifty zombies waited in ambush for the human players. The zombies had the good sense and the rare self-control to wait until all of the humans had piled into the courtyard before they sprang from the bushes and doorways. I don’t think any humans made it out alive. From then on I always felt like someone was watching me whenever I was in that courtyard.

What have been some positive elements of managing big games in real public spaces? What have been some sensitive elements you have needed to negotiate with people on or adapt to?

This game has led to my relationship with my girlfriend and friendships with some of my favorite people in the world. That is also one of the most common things I hear about people’s experience with games around the world. It’s the reason they met their wife. It’s the reason they met their friends. It’s the reason they found a social group at school. Being set in a public space makes it easy for anyone to feel ownership over the experience and to feel an equal part in the experience. Setting games in a public space is a great equalizing tool.

There is, of course, the issue of non-players. Our game can be disruptive. Many people’s understanding of appropriate use of public space does not include games like HvZ. There is also the issue of the use of toys that resemble guns. There are many people who have a problem with these things. An important lesson we needed to learn was that our actions and our game really did have the capacity to negatively impact people. Our game did not exist in a vacuum. We were able to solve all of our issues by speaking to those people who had complaints and dealing with each other’s issues respectfully and appropriately.