Rock

There’s no denying it, all photographers seem drawn to the mountains, unsurprisingly as they provide some of the most dramatic landscapes on the planet. Photography aside, to stand on a peak at dawn looking at the world stretched out beneath you is one of those experiences to connect you with the very roots of your soul. It’s a tough environment to work in though.

Getting to where you need to be for that epic vista can be somewhat tricky, to say the least. You can use mountain roads and cable cars, but depending on how far you want to take it, sooner or later you’re going to have to get your boots on and walk. There’s no getting away from it. Lugging gear up hills is just part of the job. I was two inches taller before I was a photographer. A mountain photographer will first and foremost have to be a mountaineer, willing and able to deal with all extremes of weather and terrain. Mountaineers though are obsessed with only one thing – The Route – while we photographers are fixated solely on The Shot. To be in the right place at the right time high in the mountains for that ultimate image can be a complex logistical challenge involving many nights spent camping in the thin air. Tough choices about what can be carried on the back have to be made – another lens or more food?

In an ideal world I would have the panoramic camera there on a lofty ridge with both 90mm and 180mm lenses, and also my complete DSLR system with lenses ranging from 15mm

Laguna Miscanti and Cerro Miñiques, The Andes, Chile

We’re camping up at Laguna Miscanti, which lies high in the Chilean Andes above the Atacama Desert. These mountains are dry as a bone, the thin air equally so, making the Milky Way display at night the best I’ve ever seen. Normally for a shot like this I’d use a polarizer to accentuate the blue sky, but the air is so clear up here there’s no need. Normally I hate uniform blue skies, devoid of any interest, but clouds up here just don’t happen. It’s a pretty elemental shot, entirely in keeping with the environment.

• Fuji GX617, 90mm lens

Mont Blanc in winter, Le Brévent, above Chamonix, Haute-Savoie, France

The last glimmer of light from the setting sun catches the serrated ridge on the flanks of Mont Blanc on this winter evening. I’ve cheated for this one: rather than hiking here, I caught the cable car up to Le Brévent to make the most of the view across the French Alps.

• Nikon F5, 70–200mm lens

The Alps from Aiguille du Midi, Mont Blanc, near Chamonix, Haute-Savoie, France

Down in Chamonix the valley lies under a layer of fog, but up here at the Aiguille du Midi it’s a pristine winter morning with views as far as the Matterhorn. I’ve been waiting a week for conditions like this. I’m wheezing in the cold thin air with a stinking cold that will turn to bronchitis after this mountain foray. But what a view …

• Fuji GX617, 105mm lens

to 400mm, but unless I have a small army of Sherpas in support that’s just not practical. All that kit is two, maybe three, full loads on very sweaty backs. In the Himalayas I do use porters, which gives me the luxury of taking everything, but usually working high means working light. In fact taking too much gear is a mistake – eventually it will weigh you down physically and mentally. It has to be fun, a joy to be there rather than the drudgery of an endurance course. If the light and the location are dramatic enough the classic combination of an SLR with a mid-range zoom will suffice. Typically, I take a carbon-fibre tripod, my DSLR body and just two lenses; a 24–70mm and 70–200mm, along with the usual bits and pieces: cable release, polarizer and ND grad filters and, crucially, spare batteries. Up high, in the cold, with the world laid out beneath you is not a situation to be in with flat batteries and no spares. All of that can be carried with only minor damage to the spine and knees, along with the usual mountain necessities: clothing, food, water, head torch etc. But of course all this stuff is secondary to the really important gear, your eyes, which

“A mountain photographer will first and foremost have to be a mountaineer, willing and able to deal with all extremes of weather and terrain”

Val di Fassa, Dolomites, Trentino-Alto Adige, Italy

On my first trip to the Dolomites I never saw the mountains, they remained obstinately shrouded in thick low cloud and I retreated into Austria without a single picture made. It happens. Dealing with the vagaries of the weather is one of the most frustrating aspects of the job, and mountain climates are notoriously fickle. On this second visit to Italy’s most dramatic mountain range I’m luckier, and a day spent trekking around the Val di Fassa has yielded this superb location. Persistence has been rewarded.

• Nikon F5, 24–70mm lens

Lochan na h-Achlaise and the Black Mount, Rannoch Moor, Highlands, Scotland

In terms of height, the Scottish Highlands don’t really cut the mustard compared to the Himalayas, Rockies, Alps or Andes. But size isn’t everything. Atmospherically speaking, the Caledonians are second to none. The combination of low northern light, dramatic weather and an abundance of mountain and sea lochs make it a Mecca for landscape photographers, despite the unpredictable climate. It’s where the photographic bug first bit me, changing my life forever. Patience is a must when working here; I’ve had many, many fruitless trips, camping in Glencoe, listening to the sound of rain lashing the tent. It’s enough to drive you to whisky.

• Fuji GX617, 90mm lens

are constantly searching, looking at the light, considering perspectives, pre-visualizing how those soaring peaks could look in different lighting conditions.

But mountain photography doesn’t always have to be so extreme. Actually I think the tops of mountains are often overrated places; bleak, windswept and shrouded in cloud. Some of the best alpine views are of the towering snow-capped peaks rearing above verdant valleys, the juxtaposition of the two emphasizing the scale of the mountains. And no photographer can resist rocky summits reflected in a glacial lake. Mountain cultures are some of the most vibrant and colourful I’ve come across. Trekking in Nepal isn’t just about the huge vistas; the people and their villages living in the shadow of the Himalayas make for a heady photogenic mix. And the colours and faces of the Quechua, direct descendants of the Incas living high in the Andes, have to be seen to be believed.

Dawn at Lake Matheson, near Fox Glacier, Westland National Park, South Island, New Zealand

Sometimes mountains just look their best from afar. At dawn on the shores of the lake, the Southern Alps are mirrored in the still waters. I’m revelling in nature’s harmony, until a posse of boisterous backpackers arrive, destroying the mood as they shout to each other across the lake. Heathens.

• Fuji GX617, 180mm lens

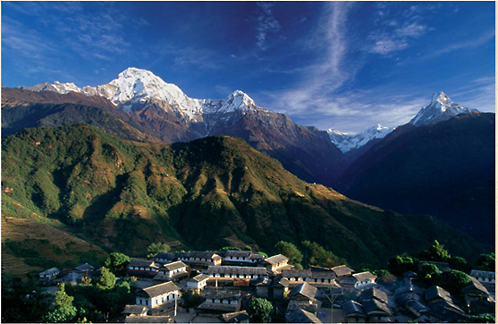

Pokhara, Nepal

The peaks of the Himalayas rise above the mist on the lake shore, impossibly high. Today we‘re off, after the joys of Kathmandu and a few days getting organized it’s time to do what we’ve spent hours talking about in pubs in Dorset, the Annapurna trek. Yesterday we met Lil, who is to be our guide and porter for the next few weeks. I felt a twinge of western guilt as I showed him the rucksack we hope he’ll carry for us. Lil is just over 5ft and only marginally taller than our monstrous sack full of decadent possessions, which we’re expecting him to lug for $5 a day. His own possessions consist of a bundle no bigger than my bum bag, all that he’ll need for several weeks in the high mountains.

Several days later we’re toiling up yet another never-ending ascent. The Himalayas are big. It’s a deeply humbling experience when a lithe and sprightly barefoot octogenarian skips past as I

puff and sweat up the third 1,500ft climb of the day. No wonder the Gurkhas are so fit. I have all my photographic gear on my back, Wendy has a day sack and Lil has the kitchen sink. Lil and I are playing a constant game of guessing how high we are. I have an altimeter watch and he’s convinced I’m cheating, but I’m not, much. The views down the valley to the steep terraced hillsides and villages perched in ludicrously inaccessible spots are absolutely breathtaking. Right now there is nowhere else I’d rather be.

We’re toiling our way up to a village called Ghorepani, where I think we’ll base ourselves for a couple of days as the vistas up there sound most promising. We’ve left roads far behind but it’s quite a busy place, with a constant stream of porters, donkey trains and other trekkers using the ancient pathways.

My gear for this trip consists of two SLR camera bodies and four lenses up to 200mm plus the panoramic beast with a 105mm lens. It’s all crammed into a photographic rucksack with a backpacking harness, which makes all the difference with such a heavy load. A carbon-fibre tripod is strapped to the back. It’s a good little ’pod and delightfully light, but I miss the height and stability of my regular piece. But all tripods are compromises, and when the only transport system is your own feet you can’t have it all. Here in early winter at this height the temperatures at night plummet and battery consumption is an issue. I’ve got lithiums in the F5s and the spot meter with a couple of spare sets. None of these villages have mains power.

At 5am the next morning we’re going up hill again, this time by the light of our head torches. My breathing in the thin freezing air is a little easier, as I’m getting used to it. To the east the first glimmer of pink light is tingeing the sky. Behind us in the gloom I’m aware of the vast bulk of Annapurna, one of the world’s few 26,000ft peaks. My pace increases as I feel the excitement and tension of what may be the shot of the trip unfolding. Up on top of the hill I turn round with gasping lungs and there is Annapurna rising out of the cloud, I’ll never forget this sight. I have a few seconds gazing in awe before battling with the tripod. With my cold fingers, getting the filter rings on the lens thread is a fuss and I’m aware of the brightening sky. I haven’t come this far and climbed this high to miss the sunrise. The sun peeks over the foothills and paints the snowy upper slopes of Annapurna. Shoot. Wind on. Check everything. Hell … the filter has misted up. Wipe it. Take another spot meter off the cloud around the mountain’s base. Reset exposure, Wendy is on filter-wiping duty as the lens is constantly misting up between frames. Shoot more, do brackets, reload. Check everything again. The cloud is now obscuring the peak. That was it, all over in maybe three minutes.

One week later and we’re ambling down the trail back from the Annapurna Base Camp towards Ghandruk with a couple of French trekkers talking about food. It has become an obsession, and our little Photographic Army of three certainly does march on its stomach. The Nepalese live on Dhal Bhat, a vegetable curry with Himalayan-size mountains of rice. It’s good healthy swag but I have to say, after three weeks of it I’d sell my soul for a bacon sandwich. Nepal has been a classic trip. Photographically it has been far more than just mountain scenes; the people and village life are unique. Lil is still with us – he’s a real star, he never complains.