Film as performance occurs when the artist engages/interacts with the projection experience as it is happening. Such actions can take place in a variety of spaces from traditional theaters to classrooms, auditoriums, gallery spaces, museums, outside viewing areas, basically anywhere a filmmaker can set up screen(s) and have electricity to power his or her projectors.

Film as performance has a fairly long history from Méliès’s initial experiments to incorporate film into his magic shows, to the films made to screen with/alongside avant-garde performances such as René Clair’s Entr’acte (1924), which played in two parts during a ballet based on a book and with sets designed by Francis Picabia, with music by Erik Satie. Malcolm Le Grice created a performance with three overlapping panels of projected film called Horror Film (1971). With his naked back to the beams of light he moved away from the projectors as color mapped the contours of his form. Carolee Schneemann completed her film Viet Flakes (1965) initially to screen as a part of her performance Snows, a criticism of the Vietnam War. The film went on to have a screening life of its own and can be rented from the filmmakers’ cooperative in New York City.

Stan VanDerBeek created his Movie-Drome (1963), a large, circular, domed screening space with multiple-format projections including slide and motion picture projection. The dome had a small entrance and the interior was all white with films and slides projected all over the walls in various sizes and speeds. The audience was invited to come in and sit or lie around the dome on pillows. There was sound from various sources but the acoustics of the dome was such that one could hear an audience member who was directly across the dome as though he or she was sitting right next to you. Movie-Drome was an immersive experience or what Gene Youngblood referred to as expanded cinema and I first read about the project in Youngblood’s book of the same name. In 2012 the New Museum recreated Movie-Drome for its exhibition “Ghosts in the Machine”. You can see interior and exterior shots from that exhibit in Figures 12.1 and 12.2.

FIGURE 12.1

An interior from the recreation of Stan VanDerBeek’s Movie-Drome.

FIGURE 12.2

An image of the exterior. Courtesy of the New Museum, New York, NY.

Another artist who pioneered film as performance was Ken Jacobs and his Nervous System Performances (1975–2000) and Nervous Magic Lantern Performances (beginning in 1990 and originally titled Nervous Magic Lantern). In the Nervous System Performances Jacobs makes use of two analyst projectors focused on the same frame (so that the images overlap), projecting a copy of the same strip of film, usually out of sync, through filters and with an exterior shutter (a fan in front of the beams emitted by the projectors) creating pulsing three-dimensional experiences. The images selected are always “found” and always old, and the performances are often silent but for the sounds of the cinematic apparatuses, although sometimes there is found audio as well. In these performances the audience could see and hear Ken and Flo Jacobs as they manipulated the projectors and devices. With the Nervous Magic Lantern Performances the Jacobs were concealed within a light-proof enclosure. They still manipulated the images with a variety of interventions between the projected beam and the screen, but the mechanics were hidden (for a better description of the differences as well as details about particular pieces, see Pierson and Arthur 2011). I first saw a Nervous System Performance at the Donnell Library in New York City in the early 1990s. It was quite a revelation as I had never seen anything like it. Jacobs seemed to be manipulating the projectors and lenses and filters as though he was playing a musical instrument, a great organ of color and light.

What is different when seeing a live film performance and either an installation or film screening is that the interventions of the performer in the work make each experience unique. The performances cannot exist without the artist, at least not in a meaningful way. Representations and reproductions of performances, as faithful as they try to be, are still very clearly flat documentation. Although they may point to the body/mind of the artist in the performance of the work by including documentation of set-up, or a wide frame taken from behind the projection so that the artist can be seen and the sounds of the performance heard, they at best allow you only to imagine what the experience would have been like as opposed to recreating it.

Movie-Drome was installed next to VanDerBeek’s house in Upstate New York, hosting a handful of screenings from 1963–1966. Viet Flakes was screened as a part of the performance Snows in 1966. The Nervous System Performances took place in the 1980s and 1990s. Since the beginning of the 21st century there has been a significant groundswell of individuals incorporating film (celluloid) as performance into their artistic practice. Some contemporary filmmakers who do so or have done so in the recent past are Devon Damonte, Lauren Cook, Ben Russell, Luis Recoder and Sandra Gibson, and Roger Beebe, among others.

The level of structure for the performances can be extremely rigorous, with specific formal/aural/image relationships happening similarly each time, or more of an embrace of the process/material and chance interactions. The individuals above all use different formats (Super-8mm, Regular-8mm, 16mm, sometimes even 35mm and various video) and they engage with sonic experience in different ways (sometimes using sound on optical tracks, sometimes using sound from other sources, sometimes, as in the case of Ben Russell’s 2011 performance cloenda Xcèntric (see http://vimeo.com/49367647), using various kinds of microphones to improvise a soundtrack.

FIGURE 12.3

This is an Elmo channel-loading projector that I purchased at a swap meet in New York City I attended with Jeff Scher in the early 1990s. Su Friedrich borrowed it to show rushes to the crew when we were working on Hide and Seek. Although I have many projectors at this point, this one is special to me because of its social history.

Favored by many artists are slot-loading projectors and most (although not all) work in 16mm film (Figure 12.3). There are different models of slot loaders. Those most commonly found in the United States are Bell & Howell, Elmo and Eiki. Slot-loading projectors enable artists to quickly thread loops into projectors during a performance so that they can work with multiple loops. If you have a projector that has to have film fed into it, it is difficult to use loops and impossible to change them quickly.

Very often the sound of the projectors themselves is an essential aspect to the performed experience, as is the body of the artist interacting with the machines. Many of the performers also make use of various material processes that we have already discussed in the book, direct animation, hand-processing, hand-made microphone and more, to create the materials for their projects. Since the performed film is so idiosyncratic to the individual performing it, I have a few examples on the website of various performances that include the artists conducting their work as well as a digital recording of the screen for Roger Beebe’s TB TX DANCE (2006).

TB TX DANCE is a film that was originally commissioned by Mike Plante as part of his lunchfilm series (http://lunchfilm.blogspot.com/). Plante takes an artist to lunch and, based on their conversation during that lunch, commissions a film from the artist for the series with criteria based on the conversations over that lunch for the price of that lunch. There is no free lunch. To date over fifty films have been commissioned this way, but Beebe’s was one of the earliest. The film was made by running clear leader through a laser printer and then making a positive and negative print (Figure 12.4). The printed area extends all the way into where an optical track would be so that the image also provides a soundtrack. According to Beebe, the idea to project the positive and negative prints side by side occurred to him while on tour. He had two projectors set up and at the end of the night in Wilmington, North Carolina, because of the unique width of the screen in a classroom he decided to run the positive and the negative print simultaneously, panning between the audio tracks. Thus his first double screen projection was born!

Beebe has made touring with his work an essential aspect of the work itself. Although he has had films in festivals and screened individual pieces without being present or as part of a program, more recently his presence, manipulation and orchestration of the work is a critical part of the art. What follows is an interview with Roger Beebe about his work, how he came to his process and the evolving community of artists and curators that he is a part of. But before I do that, I’d like to set you an assignment or two.

SHOOTING 16MM FILM IN A 35MM CAMERA

While this particular process is not necessarily about performance, its strange fluttering effect is most appreciated on repeated viewing and, because only a very small amount of film can be shot at once, it is unlikely that it will be sent to a lab (as no commercial lab would process 6–7ft of film at a time). Thus the whole act of engaging in this particular method lends itself to incorporating it into some sort of looped performance as opposed to optical printing, although that is possible too. Very simply put, this method is shooting 16mm film in a 35mm still camera. I have also had students shoot 16mm film in a 120mm camera, but that didn’t seem to work out as well, as they had to rewind the film into used paper rolls, whereas with 35mm cassettes it is still possible to purchase empties, and used bulk loaders are very cheaply purchased on eBay. Also, this process and using it as a performance have the added benefit of being extremely reasonable financially. A single 100ft roll of film will get you 16–17 rolls of film, each of which can be made into a loop and projected.

FIGURE 12.4

Scanned 16mm film strip from TB TX DANCE. Courtesy of Roger Beebe.

FIGURE 12.5

My Pentax K1000 with a 50mm Lens (a workhorse!).

FIGURE 12.6

One of a number of bulk loaders I have. I use it to bulk load 35mm movie film into cassettes for still photos as well as 16mm. In this picture the light-tight cover has been taken off and a daylight spool has been put onto the spindle. Once the cover is back on, the chamber is completely light tight.

• An old-fashioned, hand-wound (not electric rewind, these don’t seem to work) 35mm still camera. I use a Pentax K1000 and it works beautifully.

• A bulk loader and at least a dozen 35mm reusable cassettes (that is what they call the film canisters).

• 100ft of 16mm film on a daylight spool. I recommend color or black and white reversal for performance unless you want a negative image.

• Scissors.

• A changing bag or a completely light-tight space to load the 16mm film into the bulk loader. (If you decide to load it in the semi-dark, just pull off the first 5ft of film before you spool off any.)

• ⅜″ paper tape is useful to help adhere the film to the spindle as the 16mm comes out more easily than 35mm.

The process

1. In a dark room or changing bag, put the daylight spool directly onto the spindle in the bulk loader, thread the film through the slot going from the main chamber to where the cassette goes and close up the bulk loader. It’s a good idea to try this a few times in the light with some leader or a shot roll of film so you can get the hang of it. You want the film to come off emulsion in so you can wind up the film on the spindles emulsion in.

2. Take the bulk loader out into the light. Open up (if you didn’t leave it open after you were loading it) the cassette side of the bulk loader. You should see a few inches of 16mm poking out. Get a spindle and a cassette, and tape or thread the film through the spindle. Slide the cassette over the spindle and put the caps on securely. Be sure that the big part of the spindle (which will go into the winding mechanism on the camera) is up and that the cassette is in properly.

3. Close the cassette into its winding bay and wind the film until you get resistance. Some bulk loaders have a film counter that will work properly even with 16mm being wound. If this is the case, you want 36 exp. You don’t want to wind too tight or you’ll have trouble getting the film to take up in the camera and end up losing a foot or so as you try to load it.

4. Load the 35mm camera as you normally would, except you may have to use a small amount of tape to adhere the 16mm film to the take-up winder; don’t overdo it. You don’t want to end up with crud in your camera.

5. Close up your camera, set it for the ASA of the film you put in and you can use the internal light meter of the 35mm to shoot. I recommend shooting patterns and/or the same thing over and over again so that an entire roll has a similar feel. Some students have alternated textures and that also produces interesting results.

6. Once you have shot all your rolls you can take them into the darkroom or your home lab and, in a changing bag or entirely light-tight space, down-spool them into developing tanks. I like to put just a few rolls in per .5L can so that they don’t stick together. It is also possible, especially if you have rewinds in your darkroom, to bring a tape splicer in and tape splice your rolls together and then load them into a Lomo tank.

7. However you decide to process them, hang them to dry after (for about an hour until they are completely dry) and then you can make your loops and project them!

FIGURE 12.7

16mm black and white reversal film titles shot in 35mm still cameras and hand-developed as negative.

FIGURE 12.8

A still film “cassette” with 16mm film loaded in it.

Between this chapter and the first two in this book, you should probably have some facility with making very interesting direct animations. For some reason this really seems to lend itself to performance. Devon Damonte only produces animation for performance these days and he works with a group of creatives putting on shows together, sometimes projecting all the work simultaneously. So, because it is quite a lot to work up to an individual performance, for the practicum below your assignment is to find a handful of people to work with and a space, and put on a performance!

FILM AS PERFORMANCE—A PRACTICUM

1. Find a space with electricity that can be made relatively dark and can fit as many people as you’d like to attend your performance.

2. Get a few projectors and tables that you can set them on, and a wall or screen to project onto.

3. Get a couple of speakers to connect to the projectors so that you can hear the sound if there is sound film.

4. Get some found footage or make some materials that you would like to put together and make them into loops of different sizes.

5. Begin to play with the size of the various projected images, pan the sound between the various projectors, overlap your images, and put them one inside the other.

6. Take out your loops and modify them. Make them shorter or longer, or draw or paint on them.

7. Keep doing this until you’ve got something you think is interesting.

8. Invite some friends to watch and then set them the same challenge.

9. Once you have three or four film performances, have a “show” with your friends and neighbors.

10. See if you can get some musicians or poets or singers to participate as well and make live sound for the event.

11. Publicize it and make it a monthly or bi-monthly occurrence.

The two featured artists in this chapter are Roger Beebe and Peter Miller. Although they both exhibit their work primarily as performance, Beebe presents more in a theatrical setting and Miller tends towards gallery-based work. What is similar is that they both almost always exhibit their work with an audience and that audience perception of the experience is primary to the piece’s meaning. The next filmmaker I interviewed combines both performance and installation in his work and produces in a variety of formats. His name is Peter Miller and I first came across him and his work at a dinner party with friends. I was meeting people I didn’t know and the usual questions came up about what I do. Sometimes, if I say I’m a professor, people will just shrug and turn the conversation elsewhere or ask where I teach and then comment on that somehow. In this instance the couple involved asked what I teach. I said, “Film” and they said, “What kind?” and I went ahead and said, “Experimental non-fiction” and they said, “Oh, do you know our friend Peter Miller?” As I’m sure you are able to assess by now, that is not the usual response to this series of questions, particularly as they were friends of an epidemiologist friend of mine. I said, “No”, and they said, “Well you must know who he is studying with, this Austrian filmmaker Peter Tscherkassky.” I responded that I did in fact know the work of Tscherkassky and we proceeded to have a discussion about the other Austrian experimental filmmakers they had heard of and how certain artist grants that were very prestigious in Europe were virtually unknown in the United States.

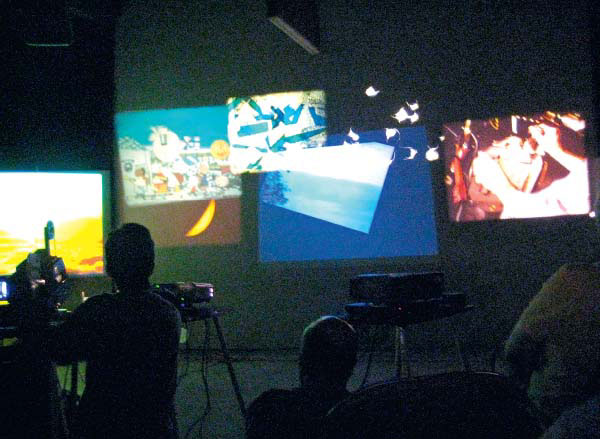

FIGURE 12.9

Emerson student Ariel Teal created a three 16mm projector performance with two loops. On the left is a loop created by adhering cut-out stickers of butterfly wings to clear celluloid and then optically reprinting it to form a loop. The right is a found print with sound that is also a loop. The loops are of different lengths so that they cycle together in a variety of ways over the 2-minute performance.

FIGURE 12.10

Emerson student David Fonseca created a three-projector performance incorporating loops on the left and right made from 16mm film shot in a 35mm still camera and a continuous strand of hand-processed film in the center. Both Teal and Fonseca made these in my class “Alternative Production Techniques”.

It was a charming change of pace from the usual dinner party discussions and then I put it out of my mind until Miller was an applicant for a position at the college where I teach. At this point I was able to see his work in some depth and, although his mixture of installation and performance was not the right fit for our position, I was so impressed with his work that I followed up with him for this book.

BIOGRAPHY OF PETER MILLER

Peter Miller is an artist living and making work in Europe. He took his MFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, is originally from Vermont and apprenticed to be a silversmith. His film and photographic works are preoccupied with magic, and generally investigate the phenomena of the cinema and its constituent, irreducible elements: lens, light, flicker, audience, projection, etc. His films are distributed by Light Cone in Paris. He is represented by Galerie Crone in Berlin. What follows is an interview with Peter about his process.

INTERVIEW WITH PETER MILLER

Kathryn Ramey: So—a general question to get the grease flowing—do you consider yourself an artist, a filmmaker, a new media practitioner, a shaman, a performer? How do you describe who you are/what you do to your aunt or the old guy next door? Or children? Yourself? Your friends? Or do you even try?

Peter Miller: I am an artist. Those four words form a complicated statement and are rightfully difficult to say. Adding modifiers just makes it more complicated. That said, the artworks that I make most often take the form of 16mm and 35mm films. The word “filmmaker” is cool, because if you say you’re a filmmaker—and there aren’t any real prerequisites to say that—people think, oh cool, I like films. And, well, I like films too, all kinds of films. But to avoid the follow-up question of why I don’t try to move to Hollywood I usually just say that I’m an artist. Granted, there aren’t any real prerequisites to say that either, but it requires a stronger courage of conviction and lets people know more accurately who I am and what I do.

When explaining the possible difference between a filmmaker and an artist making films, I have often employed the following metaphor: there are two kinds of painters in the world, both of them work with brushes and various paints. One of them tries to cover the largest amount of surface (usually a house exterior or interior) as quickly and with as little paint as possible. The other one sits in a studio (or en plein air) and stares at a blank canvas and dares to raise a brush and touch and fill that famous void. Hollywood is like the house painter; they try to deliver the best bang for your buck and they are only in it for the possible profit. The artist who works with film is more like the studio painter. They are involved in something more complex; maybe personal, maybe universal, but they are approaching the goal of painting with a different palette.

The artist is an archetype, a card in the Tarot deck of anthropology. I do not wish to reduce who people are to what they do, but there is a relationship between what we do and how we think and live and act. The artist evokes demonstrability and permissibility. Artists are a necessary component of society because of what they can demonstrate through their thinking and making, and how that in turn can open up permissions for society as a whole.

KR: How did you come to your particular practice? Did you develop your own processes as a series of experiments? Where did the ideas come from? Does your form and method change as you go and, if so, where have you been and where are you going?

PM: Coming back to the ideas of “demonstrability” and “permissibility,” the possible origins of works of art are everywhere. What artists do through their practice is develop the courage to listen carefully for the whispers and follow through in bringing them into the world. Every artist has at least two anecdotes about their art origins: one anecdote about when they first felt the potential impact works of art can have on the social world and another anecdote about how they first decided to begin contributing actively to that world.

For me, the first time that I realized the transformational potential a work of art can have happened to me while playing piano with my father. I must have been eight years old and I wanted to learn how to touch music the way that he could, with closed eyes, floating his fingers on an invisible water, drawing forth from that field all around us. While we were taking a short break, side by side, looking at the eighty-eight keys the piano offered up, he told me about John Cage’s 4′33″. The questions that I then had and the patient answers that my father gave me transformed my understanding of music, sound and art. I looked at the piano and saw an invisible, eighty-ninth key. I felt that permissibility that Cage had wrought and I felt respect for his courage to demonstrate it to us.

Around that same age I was a practicing magician. I read every book about magic that I could get my hands on. I practiced the illusions patiently before a mirror and I performed them for my friends. As I grew older and performed more frequently for adults I found that they didn’t allow themselves to enjoy the illusions as much as my peers could. After showing an illusion to an adult I was consistently asked how I did it and if I would do it again, two things that a magician is never allowed to do. I realized that adults saw my illusions as deceptions. Disheartened, I pursued other interests. I learned lock picking and I apprenticed to be a silversmith. My point of entry into the art world came by way of learning how to make 16mm films. Right from the beginning I felt real magic in the films that I was seeing and making. Magicians built the cinema. The history of the cinema begins with traveling magicians leasing the Lumière Brothers’ invention and incorporating projected moving pictures into their act. In the cinema I found all of my early interests coalescing. The film artist is confronted with a black box they cannot see into. By adding specific lights they unlock silver particles along lengths of time. I was finally able to work with magic again. Ever since then I’ve practiced making works of film art that instill wonder through everyday illusions that reveal their own natural magic.

An artist, like a magician, has a practice. They are never finished, they are always practicing, trying new things, questioning their own assumptions, inventing new methods and bettering their field for themselves, their colleagues and the people whom they hope to touch with their work.

KR: What role does media/technology/tools play in your work? What is the relationship between the media/tools and what your work is about? Is your work about something(s)?

PM: One of the greatest things about being able to say “I am an artist” in the post-studio, post-medium age is that you get to be any kind of artist you want to be. Any artist can work in any media nowadays; many work in most. To come back to permissibility again, there’s actually an imperative to make whatever it is that you feel drawn to, by whatever means or methods necessary and in whatever media it takes to bring into being the work of art that has picked you as its point of entry into the world. Because I work with 16mm film a lot, I am frequently asked the question, “Why do you work in film when you know that video exists?” Though I do make videos as well, I still feel most comfortable thinking in film. Film is to me like a mechanical language that is fairly easy to learn fluently, while video today is a digital language that nobody seems to understand completely. Many of the 16mm films that I make have the aforementioned affiliation with magic because I don’t feel much magic in video technology.

I insist that I am not being nostalgic when I choose to make a work of art with film. In my read of art history it was the development of photography and its superior abilities of representation that allowed painting to eschew the creation of landscapes and portraits, and finally be able to become what it always was: paint. If you ask me, painting only became more interesting after photography relieved it of the obligation of making portraits and landscapes. When the cinema first appeared it copied the theatre, films were made from one perspective and the audience viewed actors acting on a stage. Theatre was confronted by a new technology that could reproduce the actor’s performance identically every night and could be shown in multiple theatres at the same time. Instead of disappearing, the theatre became itself because it came back to its irreducible elements and was no longer burdened by the need to reproduce reality. Motion picture film is in the same position now, finally being relieved of the burden to reproduce reality because that’s what video is doing. I’m happy to be working with film at the time when it gets to discover its irreducible elements. Those elements are the subjects of my films. I think it odd that neither painting nor the theatre is accused of nostalgia. Since painting had to be about painting in order to become what it is today and theatre had to be about theatre, I’m not surprised that the most interesting thing for me about film right now is film itself and the filmic cinema.

Apropos the question of what works of art are about, I have an anecdote that helped me imagine another possible world that artworks can inhabit. When I lived in Boston I worked at Cinelab, a motion picture laboratory. A film student of Rob Todd’s (an incredibly prolific film artist) came in and told me about the following conversation:

Film Student: |

Hey Rob, did I tell you that I’m working on a new 16mm film? |

Rob Todd: |

“Sounds cool. What’s it like?” |

Film Student: |

“Do you mean, what is it about?” |

Rob Todd: |

“Oh … it’s an ‘about’ film.” |

KR: Where do you show your work? How do you want people to experience it? Is there a relationship between the form that your work takes and your desired venue/audience?

PM: There’s this five-sided object that artists struggle within. The five corners are:

1. The material to make the work.

2. The space to make the work.

3. The time to make the work.

4. The desire to make the work.

5. The place to show the work.

When artists meet up with other artists these are the five things that they talk about a lot. Of the five, #5, showing work, is the trickiest corner because it’s the furthest corner from the actual inception of the work. I have several 16mm and 35mm finished films that I’ve never gotten around to showing anyone. It wasn’t my goal when making them, but I think it’s a healthy, natural product of a sustained practice. Of course there’s the film festival thing. A painter can’t submit a new painting to a painting festival. Film artists have a singular channel for sharing their artworks. That said, there is also a danger that the film artist can grow to think that they actually are a Hollywood filmmaker just because they’re wearing a badge, standing on a red carpet and showing works at the same festival as Hollywood premieres, whereas the actual difference in terms of critical response, let alone goals (see house painter vs. studio painter above), is huge. If they are not careful, that can develop quickly into an art practice where #1–4 merely become the means for #5 instead of #5 being the possible outcome of a well-wrought #1–4. If an artist enters this five-sided object only because they are interested in #5, they shouldn’t be in the object in the first place.

I worked for several years as a projectionist and there’s a lot to be said for the cinema as a venue for experiencing works of film art. I can’t think of another medium that has that kind of worldwide standardization and, for an artist, it’s nice to know that certain factors such as room darkness, screen luminance and viewer positioning will be reliable. A painter doesn’t know what kind of light will fall on their painting or how large the wall will be upon which it hangs. Musicians deal with vastly different acoustics at each venue.

The performances and installations that I make in film do not usually take place in the cinema because the cinema does such a great job of hiding how it works. In projectionism (the anthropology of the projection booth) there is this reference to the Wizard of Oz and his great quote, “Pay no attention to the man behind the curtain”, because that would reveal the illusion. When we watch a film we are largely oblivious to its point of origin: the machine in the soundproof booth behind us. Sometimes after a film was finished, I’d carry the reels out of the booth and the audience would see me holding the very objects that were the film that they just saw. They would look at me slack-jawed, unable to imagine that theses things in my hands were now the things in their heads. When working with film in installation or performance, I am able to mobilize that strangeness in a way that can return a viewer to him or herself refreshed. I draw back the curtain thusly.

KR: And finally, your chapter is about film as performance. Please elaborate how you came to such an activity. Are you part of a community of makers (either locally or internationally) who communicate with each other about their work and get together either virtually or physically to discuss/show/celebrate? Where? When? How? What happens?

PM: I am lucky to have a few close friends who either work in a manner similar to mine or know me well enough to be able to help me understand where I might be trying to take a particular piece before it is even entirely clear to me. Such colleagues are rare, precious and beautiful. I try to spend as much time as I can with them because through our discussions I feel I am most myself.

According to the census, there were 288,000 people working as painters or sculptors in the United States in 2001. There wasn’t a box that you could tick off for “artist working in film”, because there aren’t very many of us. If I had to venture to guess, I’d say that worldwide there are less than a few thousand. I affectionately call this group the EFC (experimental film community). Painters form their own communities under the larger umbrella of painting, but our group is so small that we’re sort of all in it together and that brings with it inflated dramas, complex affairs and icky power struggles. Lately I’ve felt that the EFC is more of a headache and heartache than it is worth, but I hope to change my mind about that.

The American singer/songwriter (and inventor of digital fine-art photography) Graham Nash opens the song “Teach the Children Well” with some sage advice, “You, who are on this road, must have a code that you can live by.” Your code should be reviewed frequently, but it should never be abandoned. Being an artist is not supposed to be easy and you will need a light when you think you’ve lost your way. When I teach art making to young artists I always make sure to tell them that as well as a few other things. Be wary of doing other people’s work for free; your time and resources are precious and can easily fall out of balance, and they are likely going to get paid well for it. Try to find your own irreducible elements; they will be the force that drives your practice because they will be the works that only you can make. Most importantly: both your practice itself and the means you find to sustain it ought to be ethical. You will have to live with the repercussions of your work and the way that you chose to bring them into the world. After all, the following line in that Crosby, Stills and Nash song is: “And so become yourself….”

*

Peter’s interest in projection as activity and performance became a central piece of a series of works called Fulcrum. The works are called Fulcrum Film I: Flat, Fulcrum Film II: Length and Fulcrum Film III: Weight. Peter describes these works:

FIGURE 12.11

Fulcrum Film III: Weight by Peter Miller, photographed by Artur Holling. Image courtesy of the artist.

FIGURE 12.12

Fulcrum Film III: Weight by Peter Miller, photographed by Artur Holling. Image courtesy of the artist.

“Fulcrum films describe films that transform film material from a photographic image into a three-dimensional sculpture in order to showcase the projector as the place where films pivot from being unseen to being shown” (www.petermiller.info/fulcrum3.html). Each investigates a particular kind of transformation of the film. In Fulcrum Film III: Weight, film runs through a projector but, instead of being taken up on a reel, the film is tied to a large red balloon by Miller, who then releases it to the sky. As the 100ft of 16mm work their way through the projector, the balloon rises higher and higher, and eventually the film runs out. The film that has run through the projector is a slowed reprint of the Charles and Ray Eames film Powers of Ten in which the image zooms out from a blanket in Grant Park, Chicago, until the frame encompasses the entire earth.

ROGER BEEBE BIOGRAPHY

Roger Beebe is an Associate Professor in the Department of Art at the Ohio State University. He has screened his films around the globe with recent solo shows at the Laboratorio Arte Alameda (Mexico City), the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Anthology Film Archives, and dozens of other venues. He has won numerous honors and awards including a 2013 MacDowell Colony residency, a 2009 Visiting Foreign Artists Grant from the Canada Council for the Arts, a 2006 Individual Artist Grant from the State of Florida, and Best Experimental Film at the 2006 Chicago Underground Film Festival. Beebe is also a film programmer: he ran Flicker, a festival of small-gauge film in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, from 1997–2000 and was the founder and Artistic Director of FLEX, the Florida Experimental Film Festival, from 2004–2014.

As Roger is currently migrating his website from the University of Florida website, the best way to see his work and contact him is through his vimeo account. See: http://vimeo.com/user1243144.

INTERVIEW WITH ROGER BEEBE

Kathryn Ramey: How do you describe what you do and what kind of work you make?

Roger Beebe: My new job (at Ohio State) was listed as a “moving-image artist”, but that language feels really alien in my mouth (at least at this point, just one semester into the new gig). I’ve always just called myself a filmmaker (or experimental filmmaker, if I want to avoid misunderstanding, since if you say filmmaker to a stranger, s/he’ll think you want to be Steven Spielberg or something). There’s a performative element to the multiple-projector works (about which more later), but I still think of those just as films that just happen to be projected on more than one projector. In my head, I’m differentiating them from a more open, free-form, exploratory version of “expanded cinema”, which doesn’t feel at all like what I’m trying to do here, with the very strict “scores” that govern the way the different frames interact.

FIGURE 12.13

Documentation of a Roger Beebe performance. Courtesy of the artist.

When I have to clarify what “experimental” is for someone outside of the community of makers, I usually start with non-narrative (at least in my version of it), abstract, no acting, no scripts, etc. Of course, none of those things is absolute, but they point in the direction of the work I make. I also tend to emphasize a documentary impulse that’s shared by most of the work, meaning that it’s not just formal or structural (although it is also that) but it also seeks to engage with the world, with history, politics and so on.

KR: Could you elaborate on the difference between your work and what you term “expanded cinema”? What artists, either historic or contemporary, are you thinking of?

RB: I made a somewhat intentionally vague gesture toward expanded cinema partially because I think it’s an umbrella that accommodates a lot of diverse work growing out of very different traditions and using very different strategies. Most of the scholarship on expanded cinema starts by pointing to the definitional trouble. I do think the roots of the term in the 1960s with a figure like Stan VanDerBeek are part of what I’m trying to distance myself from (even though I’m interested in that work). And maybe, because of that founding in the 1960s, I fear people who hear the term might expect a more open, exploratory event than what my screenings offer. (For those interested in really digging into the world of expanded cinema, I’d recommend Jonathan Walley’s current scholarship on the subject; I can only hem and haw as an artist here, but he’s done the deep digging to really talk about that tradition. Here’s also a hilariously impossible pdf that attempts to trace expanded cinema’s various manifestations since the dawn of cinema: http://closeup.beepweb.co.uk/files/7113/1983/1835/expanded-cinema-map.pdf.)

KR: This non-narrative description is often a sticking point as (of course) it is possible to find narrative in almost everything (Michael Snow’s Wavelength is a murder mystery) but you seem to be elaborating a particular kind of difference between theatrical conventions of narrative and other kinds of storytelling. Can you expand on that?

RB: I am interested in the question of narrative, but since that’s the default mode for cinema (with documentary a distant second), I feel like I need to indicate my difference from that model up front. I’m interested in where narrative re-emerges in experimental film, but I’m mostly interested in when that happens after the radical ground-clearing of truly experimental gestures. Things that tend to get called “experimental narratives” (like Christopher Nolan’s Memento) seem pretty traditional or conservative to me, and whatever experimentation there is really happens at the fringes of the central narrative (with sync sound and all else that comes with that mode of production).

KR: How did you come to your particular practice? Did you develop your own processes as a series of experiments? Where did the ideas come from? Does your form and method change as you go and, if so, where have you been and where are you going?

RB: I don’t have an MFA or anything and have very little training in filmmaking of any sort—I took one formal class, not focused on experimental film, where I learned to load a Bolex and did a second 16mm film as an independent study—so my path to my current practice was pretty circuitous. I was at Duke to do a PhD in the Program in Literature (a critical theory program), and I started making films on the side. I had seen VERY few experimental films, so my first films were influenced by other things (Godard, postmodern metafiction, some of the more adventurous 80s and 90s indie rockers). As I was making films, I also started seeing more work, and the films of Alan Berliner, Jem Cohen, Craig Baldwin, Bill Brown, Naomi Uman and others started to trickle in as influences. It wasn’t until 2000 when I left Duke that I really made what I’d consider my first “real” experimental film (The Strip Mall Trilogy, shot in 2000, finished in early 2001). I worked (and still work) in a markedly different mode in video, and I’m less sure where that comes from. But a lot of the work since 2000 has been thematically related to The Strip Mall Trilogy, both in content and form.

In 2006, I also started (somewhat accidentally) making multi-projector works. I took my films on the road for a three-month, 7000-mile, forty-show tour, and one of the films I had with me, TB TX DANCE, I had in both a positive and negative version. Since I had two 16mm projectors with me for the tour (to avoid having breaks for reel changes), I thought I’d test out a side-by-side projection of the two prints. It ended up working better than I’d anticipated—a kind of poor-man’s cinemascope—so it planted the seed that would come to fruition in the films that followed.

TB TX DANCE was also a turning point in my interest in the use of cameraless techniques in my work. I’d done a little as early as the end of the 90s (doing direct animation on What Boys Want, hand-tinting black-and-white 16mm footage with extra-fine-point Sharpie markers), but in this last period almost every one of my films includes some cameraless techniques, whether it’s hand-processing, ray-o-grams, bleaching, etching with a laser cutter, printing directly on the film in a laser printer, etc.

The ideas are partially formal (like wanting to do single frames only in the first part of The Strip Mall Trilogy or wanting to do in-camera dissolves only for the third part) or technological (making soundtracks with laser toner by printing directly onto clear leader), but they’re also often inspired by my political and theoretical commitments. It can be something very simple, like suddenly realizing that Shaquille O’Neal’s last name is Irish and then doing research to flesh out the complex history of race (Famous Irish Americans (2003)). Often it’s something I encounter in the landscape, like the gas station in S A V E (2006) or the various AAA signs in AAAAA Motion Picture (2010). A film never really takes off for me until these various things (formal, technological, conceptual) all click into place and start working in concert.

KR: What is the relationship between your graduate work and your film work? Did you finish your PhD? What is your dissertation on?

RB: I did finish my PhD. The dissertation was on … nothing much I want to talk about now. It was a broad-ranging work of media scholarship, focused mostly on popular media like Babe (the talking pig movie), Terminator 2, Kurt Cobain, Tupac Shakur, Spike Jonze and other stuff. It was a bit of a mess as a whole, but I think there were some strong sections (a few of which exist in print in a few academic collections).

But while I don’t want to talk much about the dissertation, I do think that work still subtends my films, at least as the general backdrop against which my ideas emerge. I wouldn’t be making the films I did if I hadn’t read and studied with Fredric Jameson. Some of the films are inspired by gender studies or critical race theory. Others take something from poststructuralist linguistics. The theory is never at the center of the film (or at least not at the front and center), but it does provide some foundation for the ideas that I develop in the films.

KR: What role does media/technology/tools play in your work? What is the relationship between the media/tools and what your work is about? Is your work about something(s)?

RB: Oh, crap, did I just answer that? Maybe this is where I explain the difference between the celluloid-based work and the video work. I’ve occasionally used video as an acquisition medium (e.g. Congratulations (One Step at a Time) (2014)), but, much more often, the video work tends to be found footage. There’s a fair amount of found footage (and sound) in the film work as well, but the kinds of things one “finds” in each medium push me in very different directions. In general, the videos are much more engaged with popular culture and are much more playful. The image tends to be flatter as well, partially out of my sense that I don’t want to (or don’t know how to) make video try to simulate the beauty of film.

In the film work, most of which is in 16mm—although there’s one 35mm film (NO! (2014)) and a few Super-8mm films as well (The Strip Mall Trilogy and Composition in Red & Yellow (2002))—I like to use the resistance of the medium to help surprise myself. Many of the films are in-camera edits, which means I’m essentially shooting “blind” in the sense that I don’t really know what I’ve done until I get it back from the lab weeks later. I also have done a lot of “wrong” things while shooting, and the Bolex really offers some pretty amazing ways to do things wrong (like rotating the lens turret while shooting or back-winding and doing multiple passes on the same strip of film or doing in-camera fades with the variable shutter or tromboning a zoom lens like a teenager on acid, etc., etc., etc.). Video feels both very controlled and very malleable to me in a way that film doesn’t, and so I think I try to amplify that in the way I use each medium.

And, Jesus, I hope these films are about something. It varies pretty widely from film to film—I have a hard time saying something global like “my films deal with …”—but they’re definitely not just a bunch of pretty colors or whatever. If you watch A Woman, A Mirror and don’t get that it’s about gender and technology (and the “technologies of gender”), then I worry that the film hasn’t really succeeded (or you haven’t!).

KR: Where do you show your work? How do you want people to experience it? Is there a relationship between the form that your work takes and your desired venue/audience?

RB: Part of why I self-define as an experimental filmmaker and not a moving-image artist is that I exhibit my work primarily in film festivals rather than in museums and galleries. I prefer that context for a number of reasons. First and foremost is that I really like the darkened room and the expectation that a spectator will arrive before the film starts and stay for the duration. It’s a really special kind of attention that the film gets that way, and I hope I reward that time and attention with a meaningful experience. In the era of overload, where watching video on your laptop means having a tiny window open with lots of other distracting windows and other devices, and with beeps and alerts popping up every few seconds, I really do think that turning off the cellphone and heading into the darkened theater is a really important experience of time.

I’ve been screening less in festivals lately though, largely because the multiple-projector works are so hard to pull off technologically, and instead I’ve been showing mostly as part of the kind of roadshows that I mentioned above. I first toured with films in the late 90s when I was running Flicker, a small-gauge film festival based in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, but that program was a curated one that included only one of my films. In the early 2000s I did a few tours with other filmmakers (Tony Gault, Bill Brown) and musicians (Kent Lambert/Roommate, Nuclear Family, Erin Tobey), but since 2007 I’ve been hitting the road alone, finding ways of getting a semester off every few years in order to head out for three months at a time. I bring all my own equipment with me (seven projectors, a PA, stands, cables, etc.), so I can turn any space with a screen or a big white wall into a venue for this work. I’ve done shows in proper movie theaters, microcinemas, museums, galleries, classrooms, outdoor parks, a few planetariums, a Freemason’s lodge and more. It’s really rewarding to be in the room with an audience (and hopefully for them to be in a room with each other and with me). Part of the reason I developed these performative works is that I felt a little bored on tour when I just projected my single-channel films, so the projector performance really gives me something to do. It also makes the event seem unique every night, and I think it’s really shut down the question that I used to get asked about why not just distribute the films online and have people watch them on YouTube or Vimeo. Something special happens in that darkened room that you can’t reproduce otherwise (or at least I hope it does).

I’d say about audience that part of why I like these roadshows too is that it’s often not an experimental film audience who sees the work. The novelty of the multiple-projector format is something that draws people in who might not otherwise come, but also taking the shows to spaces where this kind of work isn’t often seen can reach some people “where they live” as it were. I do think the films tend to get a warm reception from people who don’t have any history with experimental film, so the trick is always just getting them in the room (or getting in the room where they already are).

KR: And finally, your chapter is about “Film as Performance”. Please elaborate how you came to such an activity? Are you part of a community of makers (either locally or internationally) who communicate with each other about their work and get together either virtually or physically to discuss/show/celebrate? Where? When? How? What happens?

RB: I used to really resist the idea that I was part of the show. When the audience would turn around to look at what I was doing, I’d feel like they were missing what was going on up on the screen. But I’ve come to terms with the fact that my physical engagement with the projectors is part of what people experience when I do these shows. I’ve always liked to have the projectors in the room and have people see them ahead of time and hear them during projection. Having them see me do the projection is really just part of the same gesture of laying the labor bare before them so they know (unlike when they go to a multiplex) how their sausage gets made. I hope it’s also empowering for them to realize that there’s just a regular guy running between these cranky old machines and that there’s not some mystical process that happens somewhere else, the results of which appear before them like magic.

As for a community of folks who’re fellow travelers, there are, first, literal travelers, like Vanessa Renwick and Bill Daniel (who did an enormous tour together in 2002 that provided direct inspiration for my later tours) as well as Matt McCormick, Bill Brown, Thomas Comerford, Ben Russell, Alain LeTourneau and Pam Minty, and others in my generation in addition to younger makers who’re now continuing this practice, including Alee Peoples, Charlotte Taylor, Kelly Gallagher and Lauren Cook. There has often been direct sharing of resources and networks among all of these travelers, so that we’re not constantly reinventing the wheel, and that’s been a helpful extended community to be a part of.

There are also others making work for multiple projectors—Bruce McClure, Sandra Gibson and Luis Recoder, to name just a few of the more notable examples in the United States—but I’d be reluctant to call that a community in the same way. I’m interested in the work they’re making, but it seems very different than the kind of work I’m doing. I have seen some pieces that feel a little closer to my practice—I just saw a wonderful performance by Mike A. Morris a few weeks ago for example—but there’s not (yet?) a tight-knit group focused on this part of contemporary practice. FLEXfest 2014, my final festival as artistic director, did welcome some makers who work in this mode—the Trinchera Ensemble from Mexico City, Sally Golding from London—so that was a small gesture at trying to “tighten that knit”.

FIGURE 12.14

Roger Beebe setting up for a performance. Photo courtesy of the artist.

KR: I have argued elsewhere (Ramey 2002) that the “experimental film community” is really just an expanded network of interrelated persons, groups and activities that coalesce around certain geographical and/or (for lack of a better phrase) practice-oriented interests. People come together because of shared interests and circumstances, and smaller, more tightly knit groups (what you describe as “fellow travelers”) form within this diffused web. What you describe above elaborates this idea. Occasionally a single artist/group will “surface” into the larger (more people know about and there is greater access to economic and cultural resources) art or festival world. When this happens does it impact their “membership” and/or commitment to the smaller “group”? In other words, what is the impact of “fame” or art/festival world “success” on the network, the individuals that compose it and the individual who achieves success outside the margins?

RB: I don’t think festival success generally pulls people out of the same orbit as everyone else. I mean, winning the top prize at Ann Arbor doesn’t suddenly mean you can quit your job and live off of your filmmaking! Even getting a Guggenheim (and there are a fair number of my peers who’ve done that now) just mostly means you get to take a year off from teaching. For those who cross into the art world, I guess they do disappear from these smaller groups, but I haven’t seen many successfully make that transition. (Inclusion in the Whitney Biennial doesn’t really seem to move makers from one world into the other either.) One or two filmmakers have also escaped into Indywood (and I’m thinking specifically about Miranda July, who I used to rub elbows with at festivals in Portland and Austin back in the day), and I guess they do disappear as well. But really I think the low-stakes game that is experimental film means there’s not a giant gap between those who’re having major success and those who’re struggling to place their work. I have good friends in the community at both ends of the spectrum (some of whom have moved up that short ladder, others of whom have been holding steady for the duration of our friendship). I’m wondering where I am on that continuum and whether that has a role in me being able to stay in touch with a range of makers.

There is, though, the question of geography, which is how you started your question. I do know that when I moved from Durham to Gainesville my practice changed pretty dramatically, partially because of severing the most immediate ties to the community of makers of which I was a part while in grad school. I’m not sure if my new move will have quite the same dramatic impact (partially because the community here is mostly student-based, so it’s a community of my own making; partially because I’m more sure of my direction as a filmmaker), but I expect there will be new influences and collaborations and connections that inflect my work.

I do think that experimental film is interesting in the fact that many interesting makers have spent the bulk of their professional careers outside of New York and San Francisco (in places like Iowa City or Boulder of Buffalo or … hell, Gainesville and Durham). And I think those local scenes can be interestingly idiosyncratic in a way that might be harder in those traditional “centers” of art and film. It’s a product of the place of experimental film in the academy, obviously, and maybe it’s one of the life bloods of experimental film (in the same way that regional music scenes can burst onto the national stage and reveal a whole new sound). In any case, that’s very different from the art world, where nothing counts until it happens in New York. (Yes, I know that’s a reduction, but it does at least “square the circle” of this interview by explaining once again why I call myself an experimental filmmaker rather than a moving-image artist!)

1. Find a machine that can print/make images and/or sounds.

2. Make the machine (whatever machine) do something that it wasn’t intended to do. Don’t worry if you break it.*

3. Repeat.

*Works best if it’s someone else’s machine!**

**I’m not sure I really mean that, but I know that TB TX DANCE was made under cover of night on our office printer, and I was pretty sure running film through it was going to kill it. (It didn’t. Prints just after my sessions seemed a little dusty, but that was all.) I do like doing everything wrong—changing the aperture while shooting, twisting the turret around with the Bolex running, etc.

References

Pierson, Michele, David E. James and Paul Arthur, eds. Optic Antics: The Cinema of Ken Jacobs. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2011.

Ramey, Kathryn. “Between Art, Industry and Academia: The Fragile Balancing Act of the Film Avant-Garde,” Visual Anthorpology Review, Vol. 18, Nos 1–2 (2002): 22–36.

Youngblood, Gene. Expanded Cinema. New York, NY: E.P. Dutton, 1970.