Leading a New Era of Climate Action

by Andrew Winston

CLIMATE CHANGE IS A GLOBAL EMERGENCY. It’s threatening crops, water supplies, infrastructure, and livelihoods. It’s damaging the broader economy and company bottom lines today, not in some distant future. In recent years AT&T has spent $874 million on repairs after natural disasters that the company ties to climate change. The reinsurance leader Swiss Re has seen large increases in payouts for damage caused by extreme weather events—$2.5 billion more in 2017 than it had predicted—a trend that CEO Christian Mumenthaler attributes to rising global temperatures. If we don’t move quickly toward action on climate, says Mark Carney, the Bank of England governor, we’ll see company bankruptcies and raise the odds of systemic economic collapse.

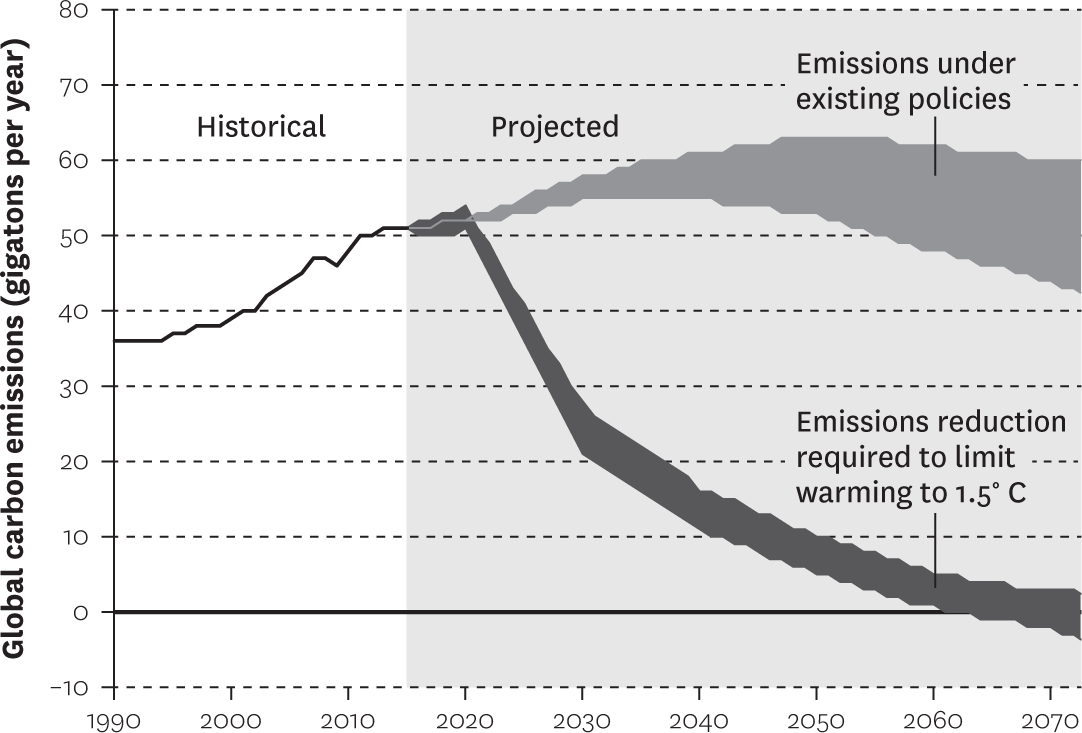

Corporate leaders are at last absorbing this; nearly every large company has significant plans to cut carbon emissions and is acting. But given the scale of the crisis and the pace at which it’s developing, these efforts are woefully inadequate. Critical UN reports in 2018 and 2019 make two things clear: (1) To avoid some of the worst outcomes of climate change, the world must cut carbon emissions by 45% by 2030 and eliminate them entirely by midcentury. (2) Current government plans and commitments are not remotely close to putting us on that path. Emissions are still rising.

Countries, cities, and businesses need to move simultaneously along two paths: reducing emissions dramatically (mitigation) and investing in resilience while planning for vast change (adaptation). My focus here is on mitigation, because adaptation alone—building ever-higher walls to keep out the sea and simply turning up the air-conditioning as the outdoors becomes uninhabitable—won’t save us. If we allow climate change to destroy the plant and animal ecosystems we rely on, there will be no replacements. The good news is that business has enormous potential to profitably cut emissions faster and even more.

If the main question for business were still “Which actions will both cut emissions and create short-term value?” we know the answer: slash carbon in energy-intensive industries and in operations, transportation, and buildings; buy lots of renewable energy, which is strategically smart because it has been competitive with fossil fuels for years; reduce waste, particularly in critical sectors such as food and agriculture; expand the use of circular business models that minimize resource use; embed climate change metrics in corporate systems and key performance indicators; and more. Again, most companies have begun to take advantage of these “basic” opportunities and will accelerate adoption as they see the payoff grow. So let’s assume that they will continue down this path. Then what?

Given the urgency, we must ask a different, and harder, question: “What are all the things business can possibly do with its vast resources?” What capital—financial, human, brand, and political—can companies bring to bear?

Drawing on 20 years of consulting to global corporations and working on climate change issues, I see three actions that companies must now focus on to drive deeper change:

using political influence to demand aggressive climate policies around the world

empowering suppliers, customers, and employees to drive change

rethinking investments and business models to eliminate waste and carbon throughout the economy

These actions may feel unnatural to some executives if they appear to put larger interests ahead of immediate shareholder profits. But the tide is turning on the very idea of shareholder primacy. The roughly 200 largest multinationals based in the United States recently declared, through the Business Roundtable, that they will no longer focus solely on shareholders or on the short run. We are at a pivotal moment as the climate crisis propels companies’ growing sense of social purpose. The result, I believe, is the will needed to finally achieve this deeper change.

What’s in It for Us?

Before I dig into the three areas of change, it’s fair to ask why a company would commit to such challenging and possibly risky initiatives. One argument is macro/societal and the other is microeconomic. The former is straightforward: Companies need healthy people and a viable planet; with expensive runaway climate change on the horizon, they have an economic imperative and a moral responsibility to do everything they can to ensure a thriving world. As Unilever’s former CEO Paul Polman says, “Business simply can’t be a bystander in a system that gives it life in the first place.” And let’s not forget that even as they pursue their own self-interest, executives sometimes just do what they believe is the right thing, which may or may not pay off—from ceasing to sell assault weapons at Dick’s Sporting Goods and Walmart to funding by Apple and Microsoft of programs to reduce homelessness in their neighborhoods.

The microeconomic argument, however, is often overlooked. Stakeholders, particularly customers and employees, have increasingly high standards for the companies they buy from and work for. Business customers are demanding more sustainability performance from suppliers every year. Consumers are seeking out sustainable brands (50% of consumer packaged goods growth from 2013 to 2018 came from sustainability-marketed products), and Deloitte’s global surveys show that up to 87% of the under-40 crowd—the Millennials who will make up 75% of the global workforce in five years—believes that a company’s success should be measured in more than just financial terms. And nine in 10 members of Gen Z agree that companies have a responsibility to engage with environmental and social issues.

Employees are now directly pressuring their companies to do more on climate, particularly in the tech sector. In direct and public appeals, Google employees have asked their executives to cut ties to climate deniers, and Microsoft’s employees staged a walkout in protest of the company’s “complicity in the climate crisis.” At Amazon more than 8,700 workers have signed an open letter to CEO Jeff Bezos with a list of demands, including developing a plan to get to zero emissions and eliminating donations to climate-denying legislators. Their efforts clearly played a part in pushing Bezos to announce large ambitions to be carbon neutral by 2040 and to buy 100,000 electric vehicles.

Alarming forecast: current climate policies are grossly inadequate

To hold global warming to 1.5° Celsius above preindustrial levels and prevent the worst impacts of climate change, the world must cut carbon emissions to zero by midcentury. Yet emissions are still rising, and under existing policies reductions won’t begin to approach what’s needed. If we stay on the current path, temperatures will probably increase by about 3° C, with catastrophic effects.

Source: Climate Action Tracker.

Note: Bandwidths represent high and low emissions estimates.

Because of pressure like this, along with increasingly dire warnings from climate scientists and global bodies including the UN, corporate efforts to reduce emissions have become table stakes—something any company must do to earn respect from employees and customers. And what is common and accepted practice, regardless of the short-term ROI, can sometimes shift very quickly. Consider that nobody could prove the value of diversity and inclusion when companies first dove into that issue. Now we have good data—but the norms changed first.

I’ve seen firsthand how this can play out on sustainability issues. Nearly six years ago, in my book The Big Pivot, I advocated setting science-based emissions-reduction goals. Virtually no companies were doing that then, and I argued with many who wondered why a company would set a goal not required by law. Now, owing to peer pressure—and because it’s rational—those goals are all but standard for big companies, with about 750 signed up and more than 200 committing to 100% renewable energy. They moved from “Why would we?” to “You’re a laggard if you don’t.”

The first companies to try the most innovative sustainability strategies are generally B Corps or purpose-driven, privately held businesses like Patagonia and IKEA, which have more leeway to experiment. The story is similar for many of the next-gen climate ideas I lay out below: Big public companies are just dipping their toes in the water, while smaller, nimbler, sustainability-focused companies take the lead. Their examples matter, because over the past decade the largest firms started emulating the midsize leaders—or just buying them. To mitigate the worst effects of climate change, more companies need to follow, and fast.

Let’s return now to the three broad activities that every company, big or small, must undertake.

1. Use Political Influence for Climate Good

Given the scale of the climate crisis, business alone can’t solve it. But business does have a powerful tool beyond its own practices and products: extensive and deep tendrils in the halls of political power. All over the world, but especially in market economies, companies have enormous influence over governments and politicians. Through large campaign donations and—in the United States after the Supreme Court case Citizens United—nearly unlimited spending on political ads, the corporate agenda gets an outsize voice in society. How can and should companies use that power?

Business’s government relations have traditionally been aimed at reshaping or fighting regulations. But over the past few years many companies have, at least on the surface, been supporting some climate policy. Hundreds of multinationals with operations in the U.S. have signed statements such as “We Are Still In” and the recent “United for the Paris Agreement” to let the world know that they will cut emissions in keeping with the Paris Climate Accords and that they want the U.S. government to stay aboard, despite announcements that it would not. Another group of large companies called for the world to hold warming to just 1.5 degrees Celsius. Signatories came from every corner of the planet: Sweden (Electrolux), Japan (ASICS), India (Mahindra Group), Switzerland (Nestlé), Germany (SAP), and many other places and sectors.

But statements alone are inadequate. Companies must lobby for the policies that will lead to a low-carbon future, and senior executives need to show up in person. Without collective government action, we have little chance of avoiding the direst outcomes of climate change. One industry—fossil fuels—has had a dominant, decades-long influence on climate policies in world capitals, and for good reason: Policies aimed at reducing emissions pose an existential threat to the business. Companies in every other sector must grasp that climate change, which may spin out of control without enlightened policies, is an existential threat to their businesses.

For the most part, nonfossil fuel companies engage only in occasional special lobbying days organized by the likes of Ceres, the American Sustainable Business Council, and Business Climate Leaders. Those events are important, of course, but even the groups themselves acknowledge that the number of big companies with a consistent climate-action focus is small. As Joe Britton, a former chief of staff for U.S. senator Martin Heinrich, told me, these temporary “fly-ins” are better than nothing, but they are overshadowed by the daily swarm of fossil fuel lobbyists. In response, Britton left his position to create a new lobbying organization, with the help of other Capitol Hill insiders, to deploy a fuller and more constant political message to Congress on climate.

There’s also a major disconnect between what companies say about their commitments to fight climate change and what those who represent them—the trade associations or even their own government relations people—actually push for. As transparency increases, companies should worry about any gap between their sustainability commitments and their lobbying. An NGO, Australia’s LobbyWatch, is calling out the mining giant BHP and others for such disconnects. And the UK-based influencemap.org is tracking corporate lobbying activity on climate at hundreds of companies and publicly highlighting hypocrisy.

For leaders, aggressive climate lobbying is not just about appearances; it can create advantage. If 100% of your energy comes from renewables, a price on carbon won’t affect your own cost structure much. And if you make products or provide services that help reduce emissions, you benefit from tighter carbon controls. That’s surely one reason that Germany’s Siemens, with a portfolio of products that improve energy efficiency, states that its top political engagement goal is “combating Climate Change.”

Hugh Welsh, the president for North America at DSM, a large Dutch company that offers nutrition, health, and sustainable-living products and solutions, can attest to this. He has worked for years to bring a business voice on climate to the halls of political power. Welsh says he does this for two reasons: principles and pragmatism. About the former, he says, “Over 10 years as president, I’ve developed political capital. I can use that just for strategic things for the business, but I can also use that to improve the world.” About the latter, he notes that DSM serves several sustainability-focused product markets, so a proactive role on sustainability and climate policy fits its strategy.

When Welsh makes the case to skeptical executives, leaders, and trade groups—such as the recalcitrant U.S. Chamber of Commerce, with which he worked for two years to flip its position on climate—he says, “If you don’t evolve your position, you’ll be on the wrong side of history … your partners and customers will leave in droves.”

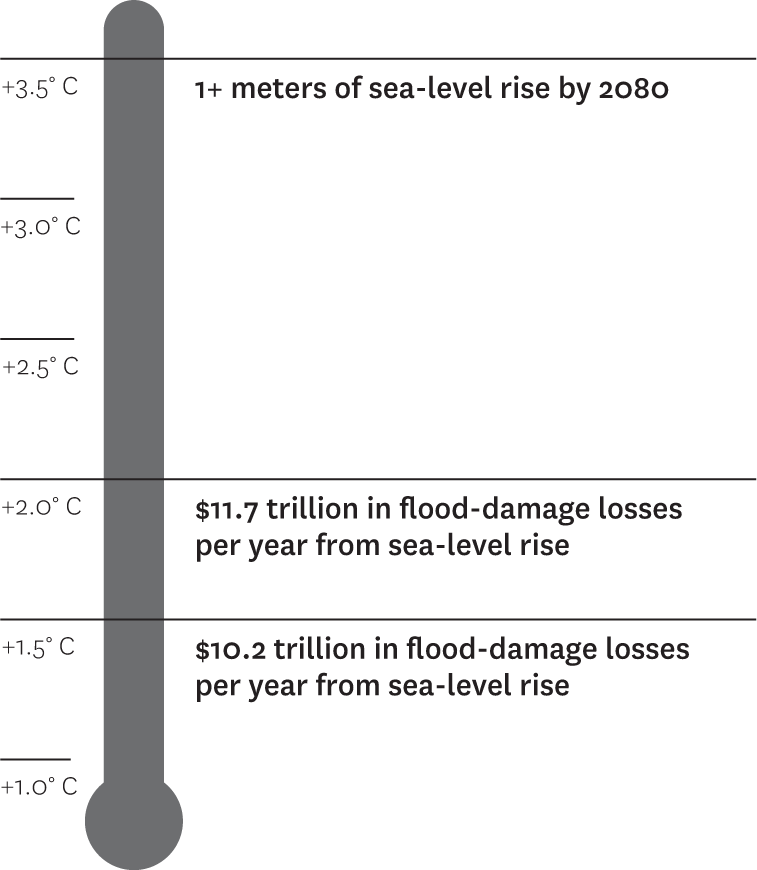

Rising temperatures, rising risks: flooding cities

If the global temperature were to increase by …

Source: World Resources Institute.

So what policies should companies advocate? To move the world to a low-carbon future, we need bold plans in a few key areas: pricing carbon and mobilizing capital to shift to low-carbon systems; rapidly raising performance standards and phasing out old technologies for big energy users like cars and buildings; and enabling transparency and efforts to reduce human suffering.

These priorities apply in most geographies, but of course policy formation and the relationship between business and government vary widely across countries. Approaches in command-and-control economies must vary from those in sprawling capitalist systems.

Policies may take years to have an effect, so these efforts must be made soon. It’s time for companies to use their substantial political influence to proactively support laws that make high-carbon products and choices more expensive, mobilize capital toward a clean economy, support systems change, and help deal with adaptation and the human costs of shifts to clean technology.

2. Leverage Stakeholder Relationships

At the same time, companies should wield their other superpower: vast influence over value chain partners and deep connections to their customers and employees. Big consumer products companies like P&G and Unilever often rightly brag that they serve billions of people every day. More than 275 million people visit a Walmart every week. Companies employ hundreds of millions of us. And with nearly $33 trillion in revenues across the Fortune Global 500 alone, it’s safe to assume that many trillions go to suppliers. Imagine if companies used those touch points, their buying power, and all their communications and advertising clout to catalyze change across business and society.

Suppliers

In recent years corporations have ratcheted up the pressure on their suppliers to operate more sustainably. Big buyers increasingly want to see progress—backed up by data—in a supplier’s carbon footprint, resource use, human rights and labor performance, and much more. General Mills, Kellogg, IKEA, and Hewlett Packard Enterprise have all set science-based carbon goals for their suppliers. Others, including GSK, H&M, Toyota, and Schneider Electric, have committed to carbon neutrality or negativity (eliminating more carbon than is produced) in their entire value chains by 2040 or 2050.

Commitments like these are becoming the norm. But what else is possible? What are boundary-pushing companies doing to drive change? I see future supply-chain climate leadership in three key areas: providing capital, driving innovation and collaboration, and using purchasing power to choose suppliers on the basis of emissions performance.

Financial assistance and capital. Making a business more sustainable is profitable, but it may still require investments and capital. Companies that ask suppliers to change how they do business can help, especially with smaller players. For example, in mid-2018, after achieving 100% renewable energy in its own operations, Apple launched the China Clean Energy Fund, a joint pool of $300 million to help suppliers buy one gigawatt of renewable energy, and the fund’s first big wind farms went up last year. Similarly, IKEA recently committed €100 million to help first-tier suppliers make the shift. In another innovative approach, an industrial company I work with, Ingersoll Rand (better known by its brands Thermo King and Trane), financed a large renewable energy project and then invited suppliers to offset their emissions by buying portions of the energy production. And beyond encouraging renewables, some leaders, such as Levi’s and Walmart, have worked with HSBC and other banks to provide lower interest rates to suppliers that score well on sustainability performance.

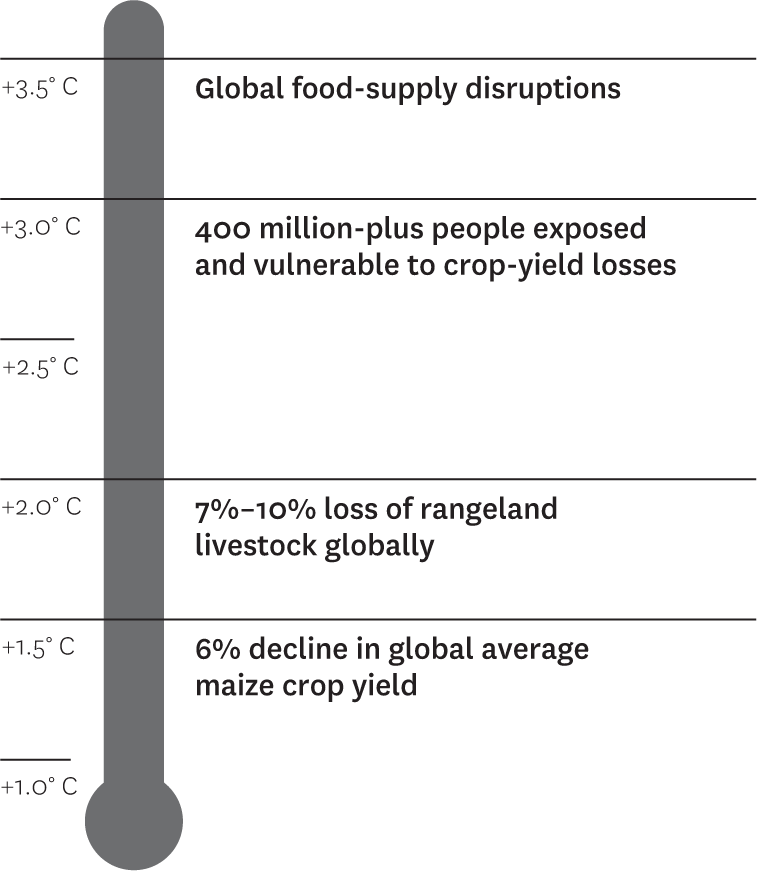

Rising temperatures, rising risks: food shortages

If the global temperature were to increase by …

Source: World Resources Institute.

Joint innovation. I also recently watched the head of procurement at Ingersoll Rand tell hundreds of suppliers that his company would no longer choose vendors on the basis of pricing and quality alone. Now, he said, suppliers would need to innovate with the company to make its products more energy- and carbon-efficient. This is a great way to drive value chain innovation, but sectorwide collaboration can have an even bigger impact.

Consider that Walmart and Target, which are traditionally competitors, worked together with the NGO Forum for the Future (on whose board I serve) to create the Beauty and Personal Care Sustainability Project—a creative attempt at improving the environmental and social footprint of all the products we put on our bodies. They brought together big CPG companies such as P&G and Unilever and their chemical suppliers to rethink ingredients, packaging, and more to reduce health and environmental impacts. Apple has dived deep into its supply chain to make its ubiquitous tech products lower-carbon, including through a joint venture with Rio Tinto and Alcoa to develop and commercialize an aluminum-smelting process with vastly lower greenhouse gas emissions and lower costs.

Purchasing power. For years many companies have agreed to work with lagging suppliers to improve their sustainability performance. But the world can no longer afford to wait for slow adopters. Companies should cut them loose and shift their purchasing dollars toward the low-carbon leaders—which are often the best-run suppliers anyway. VF Corporation, the home of brands such as Vans and The North Face, stopped buying leather from Brazil because government policy there was encouraging Amazon rain forest destruction.

Retailers should make carbon performance a buying priority. Mainstream mega-retailers like Walmart and Target have pressured suppliers for years to make their offerings more sustainable, but they could do much more to support those that are best at reducing emissions in their operations or through their products. They could, for example, permanently (not just on Earth Day) devote endcaps or special promotion areas—their highest-value real estate—to drive business to the lowest-carbon-emitting suppliers while satisfying growing customer demand for green products. It’s a win-win, but it’s not normal practice yet.

Customers

The core thing companies are doing—and must continue to do—is helping customers reduce carbon emissions by developing and offering products that produce fewer emissions throughout their life cycles. We’re seeing great innovation, and customer buy-in, for lower-footprint products in the biggest carbon-emitting sectors: electric vehicles in transportation; efficient heating, cooling, and lighting in buildings; and tasty alternative proteins in food and agriculture.

Manufacturers and retailers are also working to increase the use of recycled materials and reduce the amount of material used in packaging—all the way to zero in some cases. A group of British retailers, for example, has teamed up to change how some products leave the store. Consumers can fill their own bags and jars from bins of dry goods (grains, beans, nuts, and so on), laundry detergent, and shampoo. Some commercial products are trying to go even further: After making each tile of its prototype carbon-negative flooring, Interface explains, “there is less carbon dioxide in the atmosphere than if it had not been manufactured in the first place.”

But businesses need to make products like these mainstream and then go beyond the direct impacts of their products on customers to drive deeper change. Here are three possible ways forward:

Help customers use less and mobilize. The two most aggressive actions companies can take with consumers are encouraging them to reduce consumption and engaging them in climate activism. Zurich-based Freitag, which makes bags from recycled materials, lets customers create a new look by switching bags with other customers. And Patagonia (always a radical company) is teaching its customers how to repair its clothes so that they don’t need to buy new items. These companies may risk selling less, but they’re building trusted brands with a loyal following. And discouraging consumption hasn’t hurt Patagonia in the least: Sales have quadrupled over the past decade, reaching an estimated $1 billion. Going further, the company is using the trust it has built to mobilize consumers, through its Patagonia Action Works initiative, to engage with grassroots environmental groups in Europe and the United States.

Rising temperatures, rising risks: nature’s collapse

If the global temperature were to increase by …

Source: World Resources Institute.

Use communications to educate and inspire consumers. Companies can make more-effective use of two channels in driving climate discussions: packaging and advertising. How? The Swedish oat drink brand Oatly, for example, reports product carbon emissions on its packages and points consumers to information on the climate benefits of eating plant-based products. Ben & Jerry’s used the packaging and launch of an ice cream flavor, Save Our Swirled, to raise awareness about the Paris Climate Accords in 2015. IKEA surveyed more than 14,000 customers in 14 countries to understand their attitudes and how best to motivate climate action through advertising; the resulting framework is designed to guide its communications. In the fall of 2019 the household products company Seventh Generation donated advertising airtime on the Today show to help promote the Youth Climate Movement.

A new collaborative initiative seeks to make promotional activities like these the norm. Launched recently by Sustainable Brands (on whose advisory board I sit)—along with some big names such as PepsiCo, Nestlé Waters, P&G, SC Johnson, and Visa—the Brands for Good program commits participants to encourage sustainable living through their marketing and communications and, even more ambitious, to transform the field of marketing to support that goal.

Choose business customers wisely. The efforts described above focus on traditional consumers. But companies need to direct equal attention to their business customers. As with suppliers, they must stop enabling customers that are either not addressing climate change or, more to the point, part of the high-carbon economy. Banks, venture capital and private equity funds, consulting companies, legal firms, and other service providers should ask tough questions about whom they’re supporting. Helping companies be “better” at extracting or burning carbon-based fuels is actively moving the world in the wrong direction, and it dwarfs any carbon reduction a service business pursues in its own operations.

In the investment world, a movement to divest from fossil fuels is taking off, spearheaded by a group of investors with $11 trillion in assets. Norway’s $1 trillion sovereign wealth fund is likewise dumping investments in many oil and gas companies.

Other service companies, such as consulting giants and law firms, that still work with carbon-intensive industries should be helping them make the permanent pivot necessary to survive. That means helping fossil fuel companies sunset their core business over the next few decades and completely shift their portfolios and business models toward clean options. Tech companies have to do some hard thinking as well. One of the reasons Amazon’s employees rebelled was the company’s announcement that its cloud business would help oil and gas companies accelerate exploration. Stakeholders will continue to ask probing questions about what companies stand for and whom they support—and companies will have to have an answer.

Employees

In the battle for talent, especially for Millennials and Gen Z, companies must prove that they are good citizens. Surveys consistently show that people under 40 want to work for employers that share their values. As Unilever’s sustainable living plan gained steam in the mid-2010s, the company became the most sought-after employer in its sector. Top executives I’ve worked with at Unilever cite its sustainability leadership as key in attracting and retaining talent. The benefit flows both ways: Companies need their employees’ commitment and buy-in to achieve their sustainability goals.

To reinforce this relationship, companies must build sustainability and climate action into their regular incentive structures and systems—that is, pay everyone from the C-suite on down to cut carbon. They are secretive about the exact percentages, but the most committed companies I’ve seen tie at least a quarter of bonuses to sustainability key performance indicators (KPIs). It’s time to increase that.

Can companies go even further and proactively support their employees’ values by helping them drive change in the world around them? Some organizations already do. During the 2018 U.S. election, more than 100 of them, including Walmart, Levi Strauss, The Gap, Southwest Airlines, Kaiser Permanente, and Lyft, joined the Time to Vote initiative, giving employees time off to be good citizens. Some even encourage direct climate activism. Having identified the “climate emergency” as a top employee concern, the $1 billion cosmetics retailer Lush closed 200 shops in the U.S. to allow employees to join global climate marches last September. A Lush representative told me that during Canadian marches the company also shuttered 50 shops and offices for 20 manufacturing and support teams.

Atlassian, the fast-growing Australian enterprise software company with a $30 billion market cap, also encourages employees to become climate activists. As the company’s cofounder Mike Cannon-Brookes wrote in his blunt blog “Don’t @#$% the planet,” Atlassian gives employees a week each year to volunteer for charity, and they can now use the time to join marches and strikes. He wants them to “go further and volunteer their time to other not-for-profit groups with a focus on climate.”

Employees want to work for a company that stands for something. But they increasingly also want the freedom to express what they stand for. So ask them what they care about—especially younger and newer employees—and help them live their values.

3. Rethinking the Business

Flexing political muscle and reconceiving stakeholder relationships must happen quickly. But it is also time to think big, to look for new possibilities, and to question core assumptions about consumption and growth in the economy—that is, to go far beyond simply slashing energy use and buying renewables. Today the possibilities are broad, with everything from reducing food waste to developing circular business models falling under the umbrella of “climate strategy.” Now is the right time to think critically and creatively about how all products and services in every sector are created and used and to squeeze carbon out of every step in the value chain. Some of this is tactical—for example, working with suppliers or customers to reduce their emissions, as discussed. But at the strategic level it can mean rethinking the company’s investments and business models entirely. Here are some ways to do just that, focused on two key areas.

Risk and investments

Companies deploy capital and make investment decisions in multiple ways. With some important changes in how they think about financing and investment, much more capital could flow to low-carbon activities.

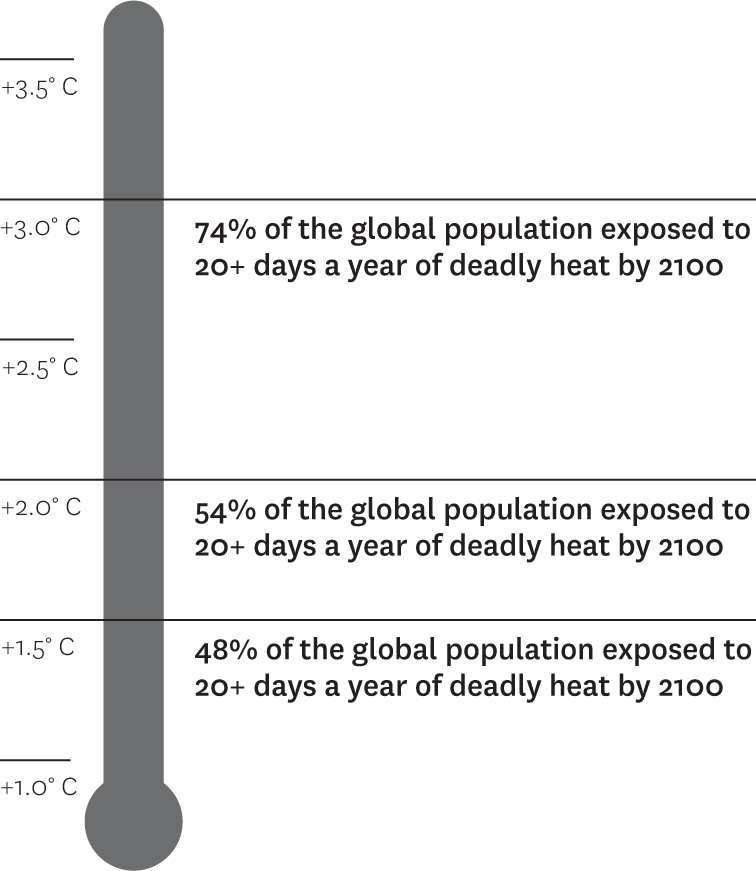

Rising temperatures, rising risks: heat waves

If the global temperature were to increase by …

Source: World Resources Institute.

Note: According to research published in Nature Climate Change, “deadly heat” is the threshold beyond which air temperatures, humidity, and other factors can be lethal.

Consider the idea of return on investment. In most companies, to get internal funding, a project must achieve a predetermined rate of return (or hurdle rate) that will pay off relatively quickly. This approach to ROI is flawed. It generally measures the “R” in straight cash, without allowing for more-strategic or intangible value. It’s also agnostic as to whether the investment moves the company down a more sustainable path. We need to use this tool differently to shift to low-carbon investment choices.

Smart tweaks to two internal processes—capital expenditures and hurdle rates—can do a lot of good. J.M. Huber, a family-owned business that manufactures nature-based ingredients for the food and personal care industries along with components in home building, developed a more holistic approach to optimizing capital deployment. The chief sustainability officer and the CFO worked together to shift the capex process to factor in intangible benefits such as community engagement, customer perceptions, employee attraction and retention, and business resiliency (for example, solar array projects that insulate the business from fossil fuel energy price shocks).

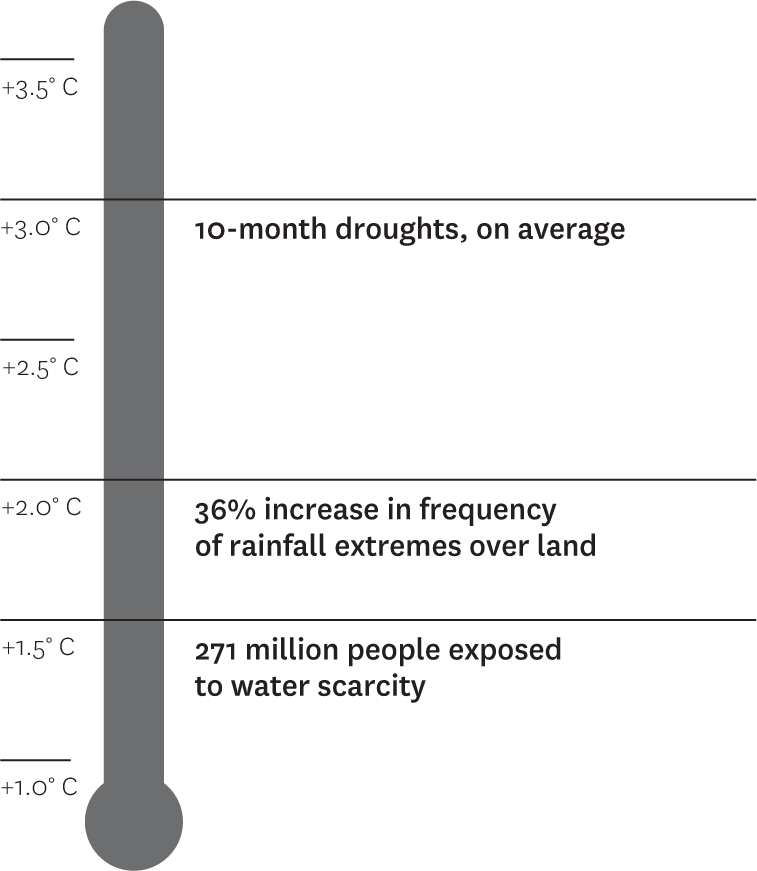

Rising temperatures, rising risks: water uncertainty

If the global temperature were to increase by …

Source: World Resources Institute.

Note: According to the NOAA, “extreme rainfall” can be loosely defined as a month’s worth of rain for a given region falling in a single day.

Companies should set their hurdle rates more strategically and allow some investments more leeway, with a strong bias toward funding carbon-reducing projects. If, for example, constructing an energy-efficient building—one that will save money and carbon over its lifetime—costs more up front or requires more than a few years to pay off, isn’t it still a smart investment on a 40-year asset?

Another wise investment shift involves levying an internal carbon price on companies’ own operations to encourage emissions reduction. More than 1,400 organizations now use internal pricing in some way, but the norm is to use “shadow” prices with no money changing hands. That approach isn’t strong enough. Early leaders like Microsoft, Disney, and LVMH have been collecting real money from divisions or functions related to their emissions. That “tax” revenue is reinvested in energy efficiency, renewables, or offset projects such as tree planting. All companies should use this strategy to help fund low-carbon projects and to prepare the business as government-imposed carbon taxes become more common.

A more recent strategy is to use financing tools such as green bonds, now a $200 billion market, in which the proceeds from bond purchases go to environmental and climate projects. The Italian energy group ENEL is trying something a bit different, issuing a bond tied to a KPI measuring the company’s performance against the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals. If ENEL misses its target of increasing renewable energy to 55% of its installed capacity, it will pay 25 basis points more to bondholders. Although the funds raised are not tied to a specific use, as they are with conventional green bonds, the instrument clearly supports emissions reduction.

Perhaps the biggest move a company can make is to rethink where to place its R&D bets. In a telling seismic shift, Daimler announced that it would no longer invest in research on internal combustion engines and would put billions toward electric vehicles instead. And the CEO of Nestlé, Mark Schneider, spoke recently about investing in plant-based proteins, which have a much smaller carbon footprint than conventionally produced meat, saying, “A Swiss franc we spend developing the burger is a burden to this quarter’s profits. Next year or the year after, it will come back to us if we do our job right.” Seeing returns on a fast-growing new market within a year or two sounds like a good deal.

New business models

The level of carbon reduction that the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change says is required to head off catastrophic warming—cutting emissions in half by 2030 and to zero by 2050—is daunting. Everything discussed here will move us much more quickly, but some fundamental changes are needed in how we think about products, services, and consumption. Current business models and delivery methods can lock us into more material- and energy-intensive pathways. And some sectors, the most carbon-intensive, will need to exit core businesses.

Consider Philips Lighting, which launched a “light as a service” model, through which business customers pay Philips to install and manage their lighting rather than purchase a lighting system themselves. This flips Philips’s traditional model on its head: Instead of trying to sell as many bulbs as possible, under this program, the company manages the provision of light as frugally as it can, using longer-lasting, more-efficient products that slash material and energy use. In a larger-scale transformation, the energy company Ørsted—formerly known as Danish Oil & Natural Gas—anticipated the decarbonization of the global economy and began pivoting from its core business a decade ago. It has since sold off most of its fossil fuel assets and has become the world’s largest builder of offshore wind farms. And just a few years ago, the idea that meat-based McDonald’s and Burger King would both be selling plant-based “burgers” seemed far-fetched. But they, like Ørsted, may be thinking strategically about what the coming low-carbon economy means for their business.

The Next Level of Action

There’s no doubt that companies are doing a lot on climate, including cutting emissions and setting aggressive carbon goals for operations, supply chains, and their innovation agendas. But it’s not enough. The science is getting away from us, and we’re losing the relatively stable planetary temperature range that allowed us to build our society over the past 10,000 years. Companies have many levers to pull to truly change business as usual, but most remain stuck in old thinking. Climate action is usually focused on incremental change. And even when they’re setting a big goal like going to all-renewable energy, companies have waited until every project makes money quickly. Now they need to mobilize all corporate assets, hard and soft, to tackle this shared, unprecedented problem at the scale it requires.

Next-gen climate actions, as they become an expected part of business, will create significant long-term value. They will help companies build closer, lasting connections with key stakeholders; create clear and consistent regulatory environments that enable more sustainable practices that lower costs; and drive deeper, more-disruptive (or what I call heretical) innovation. Throw in the substantial intangible value—employee attraction and loyalty, lowered risk in supply chain, resilience, license to operate, societal relevance, and preparation for a very different future—and you have a powerful business case.

But it’s also well past time to recognize that aggressive climate action is necessary if humanity is to survive and thrive. Business and society won’t succeed unless and until we do all we can to tackle climate change.

![]()

Your Company’s Next Leader on Climate Is … the CFO

by Laura Palmeiro and Delphine Gibassier

If your chief financial officer is the last person you would think of to take charge on climate change, think again. Today, smart organizations are shifting their sustainability responsibilities toward the finance function.

There are several reasons for this change. First is the basic math, which falls largely within a CFO’s purview. Mitigating and adapting to climate change will require close to $1 trillion in investments per year through 2030 for the economy as a whole, and is also expected to put at risk between $4.2 trillion and $43 trillion of tradable stock exchange assets by the end of the century, depending on the level of planetary warming. (The latter number is for a world that has warmed by 6 degrees Celsius.)

Second, cutting greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions leads to cost savings. If you cut emissions, you cut energy, which is a massive organizational cost—something CFOs pay close attention to. Third, because investors are pushing to make climate-safe investments, they want climate risks to be integrated within corporate financial disclosures. Finally, the business opportunities for climate change solutions are blooming. According to Chartered Professional Accountants of Canada, “As creators, enablers, preservers and reporters of sustainable value, accountants can make their organizations’ adaptation efforts more effective.” Taken together, these shifts are leading finance teams to include what were formerly called “nonfinancials” in their daily jobs.

CFO leadership on climate change is starting to pay off. For example, Adnams, a British brewery, recently saw an increase in the base cost of beer because hot summers were affecting barley production. To solve the problem, the CFO was able to offset these higher costs by looking at energy and water savings. The CFO of Mars, Claus Aagaard, has talked about how the company’s sustainability plan allowed it to capitalize on cost savings within two years.

Through our research, our corporate experience at Danone, and our work with the UN Global Compact, we have determined four key ways in which sustainability is being centralized in the finance function—ways every corporate leader should be aware of.

Financial Tools Are Becoming More Green

Increasingly, we’ve seen finance teams greening more of their tools. What does this look like? Companies such as SSE or the Coca-Cola Hellenic Bottling Company, for example, have implemented “green CAPEX [capital expenditure]” systems. These structures, which involve small changes in investment decisions (like including an internal price on carbon emissions or loosening the payback period for investment decisions), have allowed climate change–friendly investments to take place on a larger scale.

Even more significant, Microsoft now has an internal carbon market codesigned by the finance and sustainability teams. Thanks to a carbon fee paid by subsidiaries based on the level of their GHG emissions—incentivizing them to cut their emissions—Microsoft has a carbon fund that fuels climate change–related investments, allowing more significant and global investments to be made. On January 16, 2020, Microsoft made a historic announcement, backed by its CFO, to become carbon negative by 2030 and remove their historical carbon emissions by 2050.

In fact, more than 600 organizations say they now use carbon pricing, for a number of different reasons, among them to inform procurement and R&D decisions, help suppliers transition to a low-carbon world, pay bonuses, or help with long-term investments. In another change, Danone has started rewarding strong group performance by connecting incentives to climate change performance based on annual CDP scores.

Finally, following the integration of climate change within management control systems, corporations have started to measure GHG emissions like they measure their financials. Oracle has used what it calls “environmental accounting and reporting” to capture and transform GHG emissions from the company’s portfolio of 600 buildings across more than 70 countries. This has led to significant cost savings, because accurate data is being collected quickly. Even the small French company Saveurs et Vie, which produces food baskets for the elderly, has asked its enterprise resource planning system provider to allow it to automate carbon footprinting.

Finance Teams, Collaborations, and Roles Are Evolving

Changes in finance and accounting departments are increasingly visible within not only the tools but also the teams. Ørsted, a wind-power company based in Denmark, has a full-time environmental, social, and governance (ESG) accounting team made up of four employees. The UK-based energy provider SSE has a full-time sustainability accountant in-house. Since 2013, Unilever has had a finance director for sustainability, who is in charge of developing an understanding of sustainability in finance, integrating sustainability into finance reporting, and developing best practices.

These company-specific examples are giving way to larger collaborations, too. The CFO Leadership Network, created in 2010 by Accounting for Sustainability in the UK, recently developed two Canadian and U.S. charters.

Some are rethinking the traditional CFO role altogether. In 2018, the Institute of Management Accountants published the first study on the emergence of sustainability CFOs (coauthored by one of us, Delphine), demonstrating the need for specific hybridized competencies between finance and sustainability to answer today’s challenges. This research uncovered new competencies these leaders need to have, including developing natural capital profit and loss accounts, identifying the cost of key externalities, and understanding the value created through intangibles. Going further, Mervyn King (who is credited with the birth of “integrated reporting” in South Africa) developed the concept of a chief value officer in a 2016 book. And in North America, Manulife brought on a sustainability accounting director as a new kind of role.

Rules and Regulations Are Changing Rapidly

Your CFO will also need to adapt to shifting financial accounting rules that address climate change–related risks and opportunities. The biggest changes stem from December 2015, when the Financial Stability Board, an international body that monitors and makes recommendations about the global financial system, established the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) “to develop a set of voluntary, consistent disclosure recommendations for use by companies in providing information to investors, lenders and insurance underwriters about their climate-related financial risks.” The new TCFD recommendations were released in June 2017 and included the suggestion that climate-related financial disclosures be made within mainstream annual financial filings and under governance processes similar to those for public disclosures.

What does this mean in practice? For one, all disclosures, including climate-related risks, climate metrics, and targets, should be reviewed by a company’s CFO, audit committee, or both. Companies also should face the future risks of their business models through scenario analysis.

In November 2019, the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB), whose mission is to develop accounting standards for financial markets around the world, published the report “IFRS Standards and Climate-Related Disclosures,” which recommended that companies address material environmental and societal issues and, more specifically, issues driven by investor pressure to disclose climate-related risks. (This was especially significant because the IASB usually does not mention climate change in accounting standards or briefings.) We expect recommendations like those from the TCFD and the IASB to continue.

The Financial Markets Increasingly Require a Focus on Climate

The financial markets are driving CFOs to look seriously at climate change. For example, the investor initiative Climate Action 100+, representing more than 370 investors with over $35 trillion in assets collectively, is urging 100 systemically important emitters to curb emissions, improve governance, and strengthen climate-related financial disclosures. Other initiatives, such as the climate benchmarks published by the European Union or the UN’s Net Zero Asset Owner Alliance, are shifting the investment world into climate-ready financing. And in his annual letter to CEOs, BlackRock’s Larry Fink emphasized that “the evidence on climate risk is compelling investors to reassess core assumptions about modern finance.” Ultimately, Fink concluded that “climate risk is investment risk” and is alerting clients that BlackRock is centering its investment approach around sustainability.

Another reason for CFOs to take climate seriously comes from investors’ appetite for green bonds—bonds that enable capital raising and investment for new and existing projects with environmental benefits. In 2019, new issuances on the green bond market reached around $250 billion overall, channeling more and more investments toward fighting climate change. Within this market, certified climate bonds, which are verified according to the type of physical asset or infrastructure they fund, allow companies to precisely align themselves with the 2015 Paris Agreement because they are consistent with its warming limit of 2 degrees Celsius. In addition to enabling the financing of environmental projects, these instruments may even represent an advantage in terms of cost of capital, since external financing can, in some cases, become indexed on ESG performance.

When Peter Bakker from the World Business Council for Sustainable Development said in 2012 that “accountants would save the planet,” he was not far from the truth. Today, accountants are increasingly prioritizing climate change inside their organizations and beyond. Your CFO should be the next leader to follow.

![]()

A Better Way to Talk about the Climate Crisis

by Gretchen Gavett

Many of us care about the climate, but it can be challenging to talk about. It’s easy to get bogged down in stats and statistics, for one. And it can be nerve-racking to approach someone if you don’t already know what their beliefs on the topic are. Sometimes, it’s easier to just keep our mouths shut.

Given the urgency of the climate crisis, however, many of us feel that silence is no longer an option. And Dr. Katharine Hayhoe, a climate scientist at Texas Tech University, is the person to talk to about how to talk about climate change. Hayhoe, whose 2018 TEDWomen talk on the subject has been viewed almost 2 million times, talks to everyone about the topic: Uber drivers, church ladies, Rotary Club members, business leaders, managers, elected officials, and more. People may have different backgrounds and views, but she’s found a strategy that works: focusing on the heart—that is, what we collectively value—as opposed to the head.

So no matter your conversational goal, whether it’s encouraging your company to act on climate issues or getting your employees to understand how the decisions they make affect your company’s climate goals, this edited interview with Dr. Hayhoe is a great place to start.

What should any leader take into consideration when talking to people—employees, clients, suppliers, etc.—about climate change?

Ultimately, whether you’re training a new employee, reviewing best practices with a supplier, or just having a conversation about climate change with a client, follow this rule of thumb: Don’t start with fear, judgment, condemnation, or guilt. And don’t start with just overwhelming people with facts and figures. Do start by connecting the dots to what is already important to both of us, and then offer positive, beneficial, and practical solutions that we can engage in.

Why have you found that this method works best? And how does it lead people toward understanding the urgency of climate change and taking action?

Often we believe that to care about climate change we have to be a certain type of person: an environmentalist, someone who bikes to work, or is a vegan. And if we’re not any of those things, then we think, “Why should climate change matter to me?” But the reality is that if we are a human living on planet Earth, then climate change already matters to every single one of us; we just haven’t realized it yet. Why? Because climate change affects the economy, the availability of natural resources, prices, jobs, international competition, and more. Failing to account for climate change in future long-range planning could lose us a competitive edge even in a best-case scenario, and potentially mean the end of a product line or an entire business in the worst case. By connecting climate impacts to what we already care about, we can recognize the importance and urgency of taking action.

So if I’m a leader, what are some specific ways in which I can communicate with my employees that sustainability is a key part of their jobs?

I would start early. During their initial training, I would explain very clearly how our products, our production, and our waste contributes to the problem of climate change. If our production is very energy intensive or produces a lot of organic waste, for example, that means we may be generating massive amounts of greenhouse gases. If our goods are transported over long distances, that also requires fossil fuels that produce heat-trapping gases. And aside from the issue of climate change, if we produce a lot of nonrecyclable waste that just piles up in landfills or the ocean, how much are we contributing to the pollution problem as well?

But I would also be sure to pair this information hand in hand with what we’re doing to fix the problems from our end and how it’s paying off. Give people analogies so it’s really clear, so they can see it. I love giving examples of how many X worth of Y we’ve reduced; for example, something like “Through increasing the energy efficiency of our facilities, we have taken the equivalent of 500 cars off the road. Isn’t that incredible? That’s what we’ve been doing through our efforts.” Or, “We have reduced our waste by 50%. That’s the equivalent of X garbage trucks of waste per year.” Or, “We are now powered by 38 wind turbines; that’s X trainloads of coal we don’t need to use anymore.”

Finally—and this is the most important part!—I’d engage the employees themselves in the solutions. As humans, we want to be part of a solution. We want to make a difference. That is part of what gives us hope and what gives us energy, the idea that we’re actually doing something good for the world.

So, for example, I might say, “We’re aiming for an even better milestone. I want your ideas to help us get to this new milestone, too.” That’s even more incentivizing, when you feel like a company encourages you and supports you and wants you to be part of their plan.

Does this advice extend to people who might not believe that climate change is that severe—or that it exists at all? What might this kind of conversation look like in a professional setting?

Only around 10% of the population is dismissive [of climate change], but they are a very loud 10%. Glance at the comment section of any online article on climate change, check out the responses to my tweets, or search for global warming videos on YouTube—they’re everywhere. They’re even at our Thanksgiving dinner, because just about every one of us has at least one person who is dismissive in the family. I do, too!

A person who is dismissive is someone who has built their identity on rejecting the reality of a changing climate because they believe the solutions represent a direct and immediate threat to all they hold dear. And in pursuit of that goal, they will reject anything: hundreds of scientific studies, thousands of experts, even the evidence of their own eyes. So, no, there is no point talking to a dismissive about climate science or impacts, unless you enjoy banging your head against the wall.

But it can be possible to have a constructive conversation with a dismissive—and I’ve had these!—by focusing solely on solutions that they don’t see as a threat because they carry positive benefits and/or are good for their bottom line. And the fascinating thing is that once they are engaged in helping fix the problem, that very action can have the power to change a dismissive person’s mind.

I want to end by asking about the importance of climate conversation over the next few years. I’ve heard anecdotally that companies are hearing more questions from younger job candidates or employees: “What are you doing? How are you addressing climate change as a company?” Does that resonate with you at all? Should companies be preparing for more conversations like these?

We see a very strong age gradient when it comes to levels of concern about climate change primarily among conservative populations, with younger people caring much more and being much more engaged than their elders. (Among more liberal populations, levels of concern are relatively high across all age groups.) At my own school, the number of students going to the president and asking, “What is our university doing?” has increased noticeably. I hear this anecdotally from colleagues all around the country, too. And when those students graduate, that’s what they ask in their interviews, because they want to be part of the solution. Young people understand how urgent the problem is, and they know that there’s no time to waste. A lot of them don’t want to do a job that is not helping to fix this massive problem that we have.

If companies want to be competitive, if they want to hire the best and the brightest, the ones who are most engaged, the ones who are most in tune, the ones who really put their heart and their soul and their passion into their work, then they have to start talking about climate change differently. Because this is increasingly becoming something that young professionals really care about.

Originally published in January 2020. Reprint BG2001