CHAPTER SEVEN

Financing Your Uncertain Future

I wish I had known what the rights of trustees were in advance, that they get to decide what funds are liquidated when and that they are represented by counsel, who is paid for out of the estate. I also discovered that one sibling can waste a lot of the trustee’s time and accordingly draw down on the estate with constant arguing and stonewalling.

—Margie, focus group participant

One of the most complex and daunting challenges that we face as we get older is trying to figure out how to manage our money in the last years of life. The problem, quite simply, is that the ending (when, where, and how) as well as the associated costs are unknowable.

Sadly, many people deal with this financial conundrum the same way they approach other challenges in the last years of life: with healthy doses of procrastination and inertia.

In fact, it has been estimated that 53 percent of Americans 25 and older haven’t even tried to calculate how much they will need to save to live comfortably in retirement, according to a March 2013 study by the Employee Benefit Research Institute.

Yet despite inaction by so many, it’s a problem that is top of mind for most Americans. More than 81 percent of respondents to a Consumer Reports survey said that they worry about being able to afford healthcare in retirement, and 68 percent worry that they’ll go bankrupt paying for medical bills following a serious illness or accident.

Even wealthier people seem frozen in the headlights. Two-thirds of people with at least $250,000 in investable assets expressed concern that they would outlive their retirement nest egg, according to a 2011 study by Bank of America Merrill Lynch.

Unfortunately, this fear of running out of money in your last years, in particular due to overwhelming medical expenses, is not misplaced. A 2009 American Journal of Medicine article reported that 62 percent of personal bankruptcies are caused by medical problems.

I don’t know about you, but I was stunned by this statistic. Then, as I began looking into the likely causes of this financial catastrophe, I realized that the Other Talk could play a significant role in overcoming the inertia over retirement planning while also directly addressing the worry of outlasting your assets.

The Leading Drivers of Financial Problems at the End of Life

The first driver is what the medical profession calls the “compression of morbidity.” The layperson’s translation of this rather gruesome terminology is that the bulk of an individual’s spending on healthcare will occur in that person’s last two years, and especially the last six months.

In other words, morbidity—the incidence of various illnesses—accelerates at the end of life, with multiple medical specialists getting into the act. This can become very costly, and it is the reason that Medicare now spends nearly one-third of its total budget on patients in their last 12 months of life.

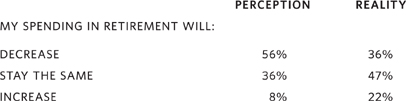

The second cause of financial problems at the end of life is that our expectations don’t come close to reflecting reality, as can be seen in the following table, which was part of a 2010 TIAA-CREF study:

Retirement Expectations

This analysis shows that 56 percent of people in the study believed that their spending would decrease in retirement. The reality was that spending decreased for only 31 percent of respondents. At the other end, only 8 percent of people in the study expected their spending to increase in their retirement. In reality, 22 percent of respondents saw their spending increase during this time.

The implication is that you will likely spend a lot more money in retirement than your financial assumptions have allowed for.

Finally, elderly parents can get in trouble because they lose the mental capacity to control their finances.

Ralph, who was in one of my focus groups, remembered standing by helplessly, watching his 82-year-old mother drive her financial wagon off a cliff:

She kept living like there was no tomorrow. She kept spending and spending and spending like she had it, except she didn’t. Piling up debt on credit cards, buying cars she didn’t need, continually overdrawing her bank account.

It was a nightmare, but I didn’t know how to stop her.

How can you explicitly deal with the causes of financial ruin: the potential healthcare train wreck in the last year or so of life, the tendency to spend too much before you realize that you are not controlling your finances as capably as you once did?

Essentially, you need a plan—not a static one, but a dynamic one that includes your spouse and your kids, who will be instrumental in implementing it.

In my view, coming up with a singular “number” is a good start, but considering it the answer to retirement planning is naive and potentially dangerous. Just ask the families who went bankrupt in the last years of their parents’ lives because of unplanned medical expenses.

What you need is the dynamism of the Other Talk, which is about managing evolution in your last years of life and addressing decision making, roles and responsibilities, asset management, living arrangements, and healthcare needs.

What you need is the adaptability and flexibility inherent in the Other Talk process, which you can achieve by committing to annual updates. This will ensure that you and your family revisit your assumptions and financial condition so that you can recalibrate your plan if the current reality requires it.

Finally, what you need to remember is that the Other Talk isn’t just about the orderly distribution of your assets while you’re alive and when you are gone. It’s also a means to an end: how to get the most out of the rest of your life and how to involve your kids in that adventure.

Discussing How to Finance Your Uncertain Future

Fundamentally, this financial part of the Other Talk should be focused on a series of what-if scenarios because your situation in your last years is forever fluid.

Physically, your condition will evolve, requiring various levels and types of medical care. Social Security and Medicare benefits may change; tax rates and policies may be rewritten. Real estate valuations can reverse course (remember when conventional wisdom held that housing prices would never go down?). And the investment environment can be volatile. Conventional wisdom had it that stocks in the long term would increase in value, yet between 2000 and 2010 the Dow Jones Industrial Average barely moved upward, although it had very volatile ups and downs in that period.

Establishing Your Spending Priorities

As a result, in preparing for the “financing your uncertain future” discussion, I recommend that you bring a contingency planning mindset as you ponder the guiding principles of this conversation: What is the life you want? What is the life you don’t want? What are the costs of each?

To answer these questions, you need to establish a clear picture of your financial situation, develop a series of what-if scenarios that demonstrate what you want to accomplish and experience, and then determine how realistically these various scenarios can exist within your financial reality.

For example, the life you want may be three overseas trips every year, plus a house in the country. The life you don’t want may be living in a nursing home and giving up driving your car. When you run the numbers, however, you realize that the costs of international travel, a second home, eventual 24/7 care in your home, and a car will consume your assets by age 71. You need to revisit the life you want and the one you don’t want.

Or perhaps you have approached the aspirations of your last years more qualitatively: I want my life to be busy, useful, flexible, relevant. I want to be always learning and physically active.

Of course, there are a number of ways to achieve those goals, each at different price points. Your job then is to pick and choose those that meet your budget.

However you think about the life you want, either quantitatively or qualitatively, I would recommend one more level of contingency planning. To maximize the fun and satisfaction in your last years, consider setting goals and priorities by decade. For example:

![]() Adventure travel, like climbing the Inca Trail to Machu Picchu, in your sixties

Adventure travel, like climbing the Inca Trail to Machu Picchu, in your sixties

![]() Guided tours, like bike trips in the Michigan countryside, in your seventies

Guided tours, like bike trips in the Michigan countryside, in your seventies

![]() Theater and museum trips in your eighties

Theater and museum trips in your eighties

![]() Extreme bingo in your nineties

Extreme bingo in your nineties

Certainly, your health and wealth will dictate whether your timetable speeds up or slows down, but at least you won’t be waiting to strike out on some adventure until it’s too late for you physically or financially.

Perhaps the most important thing to keep in mind as you consider your dreams, goals, and aspirations is that the path to true happiness is enjoying what you have: family, health, and whatever resources you’ve accumulated.

Creating Your Retirement Income Plan

Whichever approach you take to your spending priorities, you’re not finished yet. You need to bring that same what-if mindset to your assets and your budget because the world is not a static place and neither is your pile of money.

Social Security

When should you start taking Social Security? This is one of the most critical decisions that you need to make because your timing will affect not only your net worth but also your spending plans throughout your retirement years.

Past conventional wisdom held that it was best to take benefits early (for today’s 60-somethings that would be age 66) and to invest the proceeds. Of course, another reason to claim Social Security at 66, or even as early as 62, is if you’re in ill health or have a family history of early mortality—or if you simply need the money.

But experts today recommend waiting as long as you can to receive your benefits. Waiting until age 70 to collect means your monthly payment could increase by as much as 32 percent.

Available Retirement Benefits

If you are a military veteran, check with the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs to see if you are eligible for a veterans pension and other benefits.

In addition, the National Council on Aging has identified more than 2,000 different programs that can assist elders with long-term care as well as subsidies for food, medication, and housing. Check out www.benefitscheckup.org for a complete listing.

Savings

Finally, you need to analyze your nest egg to determine whether you will outlive it or vice versa. To make this determination, consider a number of variables that not too many years ago made this exercise a daunting and imprecise task but that today are readily available.

Generating Financial Projections

Fortunately, in this age of computer modeling, creating what-if scenarios has become fairly easy and straightforward. Software programs, often offered free of charge by brokerages, insurance companies, and financial planners, can help you generate a series of financial projections, each based on various spending assumptions and investment strategies.

Personal Data for the Projections

Of course, you are going to need to do your homework because your what-if projections are only as good as the accuracy of the data you provide. Depending on the software you are using, you’ll need to accumulate this type of information:

Annual Expenses

![]() Essential expenses

Essential expenses

![]() Discretionary expenses (such as travel, dining out, entertainment, and clothes)

Discretionary expenses (such as travel, dining out, entertainment, and clothes)

![]() Supplemental healthcare insurance

Supplemental healthcare insurance

![]() Long-term healthcare insurance

Long-term healthcare insurance

Income

![]() Social Security

Social Security

![]() Salary, bonus, and other work-related (earned) income

Salary, bonus, and other work-related (earned) income

![]() 401(k), 403(b), and IRA accounts

401(k), 403(b), and IRA accounts

![]() Pension benefits

Pension benefits

![]() Annuity income

Annuity income

![]() Other income (such as dividends, interest, rental income, and real estate sales including your home)

Other income (such as dividends, interest, rental income, and real estate sales including your home)

![]() Investment portfolio, including the dollar amount and percentage of total for stocks, bonds, and short-term instruments

Investment portfolio, including the dollar amount and percentage of total for stocks, bonds, and short-term instruments

![]() Real estate

Real estate

![]() Other assets (such as antiques and artwork)

Other assets (such as antiques and artwork)

![]() Level of risk you are comfortable with

Level of risk you are comfortable with

Depending on the software program, you may be able to project the future value of your assets against various market performance assumptions. More important, you may be able to estimate when your assets will be fully depleted.

What-If Scenarios

Armed with these data, you can start working what-if scenarios. For example:

![]() What happens if I change my retirement date?

What happens if I change my retirement date?

![]() What happens if I change our annual spending rate?

What happens if I change our annual spending rate?

![]() What happens if I change our asset mix?

What happens if I change our asset mix?

![]() What happens if I convert from owning to renting?

What happens if I convert from owning to renting?

Revisiting Your Retirement Plan

Finally, these software programs are useful not only in estimating an end date for your nest egg but also in encouraging you to revisit key decisions such as the following in your own personal retirement plan:

![]() How long will you and your spouse live? According to an analysis by the Society of Actuaries, there is a 25 percent chance that a 65-year-old in good health will live to 92 if male, 94 if female, and 97 if he or she is a surviving spouse from a married couple.

How long will you and your spouse live? According to an analysis by the Society of Actuaries, there is a 25 percent chance that a 65-year-old in good health will live to 92 if male, 94 if female, and 97 if he or she is a surviving spouse from a married couple.

![]() Can your investment portfolio at least match the rate of inflation?

Can your investment portfolio at least match the rate of inflation?

![]() Have you established a withdrawal rate that won’t jeopardize your long-term future?

Have you established a withdrawal rate that won’t jeopardize your long-term future?

![]() Have you set aside funds to supplement Medicare and cover out-of-pocket healthcare costs, which Fidelity Investments estimate at $220,000 for a couple aged 65, one of whom lives to 92?

Have you set aside funds to supplement Medicare and cover out-of-pocket healthcare costs, which Fidelity Investments estimate at $220,000 for a couple aged 65, one of whom lives to 92?

![]() Do you want to leave an inheritance for your kids, or is your goal like René’s, one of my research respondents: “I want the last check that I write before I die to bounce!”

Do you want to leave an inheritance for your kids, or is your goal like René’s, one of my research respondents: “I want the last check that I write before I die to bounce!”

Planning for Role Reversal

Now that you’ve run due diligence on your financial plan, both spending priorities and the ability of your nest egg to deliver on them for all of your last years, it’s time for you and your spouse to take one more step before you’re ready to sit down with the family to have the Other Talk.

The two of you need to put a mechanism in place that shifts financial responsibilities from you to your kids with as little drama as possible. By building that mechanism with your children now, it will look and feel like (and will in fact be) prudent planning, rather than a fight over financial control.

If you postpone action, thinking, “I’ll know when it’s time,” you will most likely find yourself out of the loop, losing your ability to guide an effective transition because either a sudden disability happened so fast that the rules of the game changed before you could react or creeping dementia sneaked up on you.

About half of Americans in their eighties have some form of dementia or cognitive decline. But problems usually start well before that, as noted in a 2010 study that appeared in the Wall Street Journal. According to the study by George Korniotis of the Federal Reserve and Alok Kumar of the University of Texas business school, recent research into our financial decision-making skills suggests they begin to slip after age 70 and suffer more rapid declines after 75, much as aging athletes lose speed and agility. As a result, your mental decline will be incremental, most likely so gradual that you won’t even notice (although those around you increasingly will). So, like the over-the-hill athlete who refuses to leave the game, you’ll insist on maintaining your position until your kids are forced to drag you off the field.

Nobody wins that one. So let’s consider the Other Talk approach.

Step 1. Establish a Financial Power of Attorney

If you have more than one child and all or some of them will be participating in the Other Talk, I recommend dividing up the responsibilities among them:

![]() One child could oversee the finances and handle all the bill paying.

One child could oversee the finances and handle all the bill paying.

![]() Another could monitor the medical diagnoses and treatments and stay on top of doctor visits.

Another could monitor the medical diagnoses and treatments and stay on top of doctor visits.

![]() A third could be in charge of the home maintenance or be the liaison with the assisted-living center.

A third could be in charge of the home maintenance or be the liaison with the assisted-living center.

That way all the kids have a responsibility, nobody feels overburdened and eventually underappreciated, and the opportunities for sibling disagreements are reduced.

When choosing the child who will handle your finances (I’ll get to the other two choices in later chapters), Linda Kaare, a Michigan elder-law attorney, urges that you should select “someone who is organized, dependable, and trustworthy and is financially stable in his or her own life.”

In addition, you should be honest about the amount of work and the challenges involved. When it came time for me to take over the financial responsibilities for my parents, I found the tasks—paying bills, making investment decisions, and filing tax returns, to name a few—fairly time-consuming and ongoing, especially since my parents and I lived in different states.

There are shortcuts, however, like electronic banking and automatic withdrawals for recurring expenses, like home healthcare, utilities, and phone bills, which will save time and allow the kids to monitor your accounts for correct deposits and withdrawals.

In addition, keeping an eye on the money can help your kids protect you from financial scams that target older Americans, which have become so prevalent that the National Council on Aging, on its website, calls them the crime of the century:

Why? Because seniors are thought to have a significant amount of money sitting in their accounts. Financial scams also often go unreported or can be difficult to prosecute, so they’re considered a low-risk crime.

However, they are devastating to many older adults and can leave them in a very vulnerable position with little time to recoup their losses.

Here’s just one example from National Council on Aging’s top-10 list of scams that illustrates how easy it is for someone in the last years of life to be separated from his or her money:

The Grandparent Scam is so simple and so underhanded, because it uses one of older adults’ most reliable assets, their hearts. Scammers will place a call to an older person, and when the mark picks up, they will say something along the lines of, “Hi, Grandma, do you know who this is?” When the unsuspecting grandparent guesses the name of the grandchild the scammer most sounds like, the scammer has established a fake identity without having done a lick of background research.

Once “in,” the fake grandchild will usually ask for money to solve some unexpected financial problem (overdue rent, payment for car repairs, etc.), to be paid via Western Union or MoneyGram, which don’t always require identification to collect. At the same time, the scam artist will beg the grandparent, “Please don’t tell my parents; they would kill me.”

Once you have settled on which of your children you want to help you manage the finances and that child has agreed to take on that responsibility, you need to make your choice known to the family. Then you should move on three fronts, and I urge you to act quickly.

Documentation

To begin, you should execute a financial power of attorney, which is basically a written, signed, and notarized document through which the parents give the designated child the authority to manage the parents’ money—the right to do everything from writing checks to selling securities. Powers of attorney can be effective immediately or upon incapacity. Unfortunately, it seems that assigning a financial power of attorney is an easy task to procrastinate. In a 1991 survey, nearly three-quarters of Americans 45 years and older said they hadn’t gotten around to it, according to AARP.

Because you can write your own definition of “incapacity,” I would strongly encourage you to get to this document as soon as possible. The most common definition requires two physicians to declare the person incapacitated.

Power of attorney documents are usually drafted by lawyers, but they don’t have to be. You can find templates on Internet websites, some of which are listed in the Appendix “Online Resources for the Other Talk.”

Financial Assistance

Sit all your kids down for face-to-face meetings with your financial advisors: banker, lawyer, broker, accountant, insurance agent, financial planner, and any others as needed. The purpose is to get acquainted in preparation for future dealings and for everyone concerned to understand your financial strategies and tactics, as well as how things have been set up.

If you don’t currently use advisors, then when you first get together for the Other Talk, you should discuss with your kids the pros and cons of getting financial assistance. You may decide that outsourcing some of your financial decision making and execution may provide your family with useful expertise while also reducing familial friction and leaving time for all of you to do other things.

Asset Distribution

The third point to make with your kids, especially the one handling the finances, is that under current U.S. law, spouses who are U.S. citizens can pass unlimited assets to each other, either during their lifetime or after death. Distributing assets to other beneficiaries, however, including the children, is subject to certain limitations. To understand the rules, your family should consult with a tax and/or financial planning expert.

Step 2. Simplify Your Finances

As you probably discovered when you began to put together the notebooks that I discussed in Chapter 6, “Getting Your Documents in Order,” you’ve got stuff all over the place. While the notebook technique enables you to consolidate all your financial matters physically, I would also ask you to simplify your finances structurally as well. For example:

![]() Have your monthly checks (such as dividends, annuities, and pensions) deposited automatically. (Your Social Security payment is probably already automatically deposited.)

Have your monthly checks (such as dividends, annuities, and pensions) deposited automatically. (Your Social Security payment is probably already automatically deposited.)

![]() Put as many bills as possible on autopay (including utilities, memberships, house of worship pledges, and ongoing charity donations).

Put as many bills as possible on autopay (including utilities, memberships, house of worship pledges, and ongoing charity donations).

![]() Consolidate your checking and savings accounts to one bank.

Consolidate your checking and savings accounts to one bank.

![]() Transfer investment holdings, including IRAs, profit sharing, and 401(k) and 403(b) accounts, to a single financial services company.

Transfer investment holdings, including IRAs, profit sharing, and 401(k) and 403(b) accounts, to a single financial services company.

The bottom line is that the more you put on autopilot, the better off you will be as you move into your seventies, eighties, and beyond. For certain, the kid you designated your financial power of attorney will appreciate you for it.

Step 3. Transfer the Roles Between Your Spouse or Partner and You

In preparation for discussing financial role reversal in the Other Talk, one area that often gets overlooked is the potential need to shift responsibilities from one spouse to another if one becomes incapacitated or dies. You’ll want to prepare for this.

Let’s say you have been handling the bill paying and your partner has been the hands-on investor as your nest egg began to grow.

You should give your partner a tutorial and possibly a road map of the payment process (such as autopay, e-mail, and mail); the monthly budget, if it exists; and the location where the receipts are kept.

Your partner should provide you with a detailed summary of what financial resources are available (and hopefully that summary is housed in the Other Talk binder by now), and he or she should walk through the what-if scenarios in the plan discussed earlier in this chapter.

Once you’ve both been briefed on each other’s roles, you should determine the trigger points that will prompt the other partner to take over. Since this transfer of roles likely means that one partner is taking on both bill paying and investing, he or she should determine the following:

![]() How much responsibility to retain personally

How much responsibility to retain personally

![]() How much to pass on to the kids

How much to pass on to the kids

![]() How much to turn over to an outside expert

How much to turn over to an outside expert

Since these determinations will have important implications for the kids, they should be made part of the Other Talk.

Next Steps

We’ve just spent an entire chapter on ways to manage your money during your last years of life. Our financial planning story won’t be complete, however, until we deal with steps to be taken to avoid financial hassles after the death of a parent or a spouse.

Create a Password Library Card

In this increasingly digital world we live in (and depend on), it is no longer good enough to leave just a safety deposit box key with your spouse and kids for when you pass on. Quite simply, many of your documents and your protocols for accessing your assets probably aren’t housed in that box. Most likely, a lot of the really important stuff is sitting on your hard drive inside your computer.

As a result, you need to create a password library card, then find a secure place for it—definitely not your computer but perhaps in your safety deposit box.

On the card be sure to list your log-in and/or user name, password, and other prompts, such as your answers to security questions, for as many electronic relationships as you can think of, including these:

![]() E-mail accounts

E-mail accounts

![]() Computers

Computers

![]() Social media accounts

Social media accounts

![]() Online accounts for retailers

Online accounts for retailers

![]() Online accounts for ongoing bill paying (for example, utilities, mortgage, and charities)

Online accounts for ongoing bill paying (for example, utilities, mortgage, and charities)

![]() Frequent-flyer accounts

Frequent-flyer accounts

![]() Tablets, music players, and digital readers

Tablets, music players, and digital readers

Establish Joint Ownership

One layer of grief you don’t want to lay on your surviving spouse or kids is locking up your assets because they’re only in your name. Your family could spend months and lots of legal fees trying to gain access to funds that they may need in the short term.

It would make sense and be relatively easy if you go back to the binder that I discussed in Chapter 6 and make sure that all your assets (including your checking account) are in joint ownership with your spouse or partner and that your listed beneficiaries are up to date.

Unwind Joint Accounts … Carefully

On the subject of joint checking accounts, I have heard a number of horror stories of surviving spouses’ automatically taking the deceased’s name off the account, only to then be locked out of the account. There’s no rush to make the name adjustment, so get to it when you have less on your plate and can check with the bank on the best way to go about it.

For retirement accounts, the standard advice is to roll over the deceased’s account into your own. But if you, the surviving spouse, are under 59½, withdrawals from the consolidated IRA will trigger a 10 percent penalty.

Better to consider an “inherited IRA,” which, if the deceased was younger than 70½, allows the surviving spouse to withdraw without penalty. Withdrawals must begin the year that the deceased would have hit 70½. (Check all this out with your accountant since things change—this is not meant to be financial advice.)