CHAPTER 2

Developing Purpose, Mission, Vision, and Goals

Key Take Aways

This chapter focuses on the strategy development process for the pension fund on whose behalf investments are made. Defining a purpose and a mission, as well as explicating the values that matter are instrumental processes in shaping the investments that achieve the mission of the fund. What are the participants' needs, both in the short and the long run? How can the investments fulfil those needs? And if the participants' needs change, can the fund still provide added value, or is there a tendency to keep on going just because the organization exists? Is the mission broader than the purely financial interest of the beneficiaries? Does it include collective or societal goals? Trustees should have shared answers for these questions in the form of a mission statement before they move on to formulating strategic goals and using these to design the investment function.

A board that has taken the time to develop a strategic plan will be able to provide its pension fund and participants with direction and focus. A pension fund that does not have a clearly defined and implemented strategy will find that it is time and time again simply reacting in the face of financial, economic and regulatory developments; the organization will be trying to deal with unanticipated pressures as they arise, and will also be at a competitive disadvantage. Strategy development requires the board to carry out and take ownership of the following six steps to enable its effective implementation. Specifically, the board must:

- Define the purpose of the pension fund—why do we exist?

- Define the mission—in general, how do we realize the purpose; what is our ambition?

- Define the vision—what do we aspire to become and achieve in the next 5–10 years?

- Make explicit the values that the fund holds.

- Define the pension fund's strategic goals—how do we go from where we currently are to where we want to go?

- Facilitate and monitor the implementation strategy—develop a set of actions, measures and plans to achieve the formulated goals.

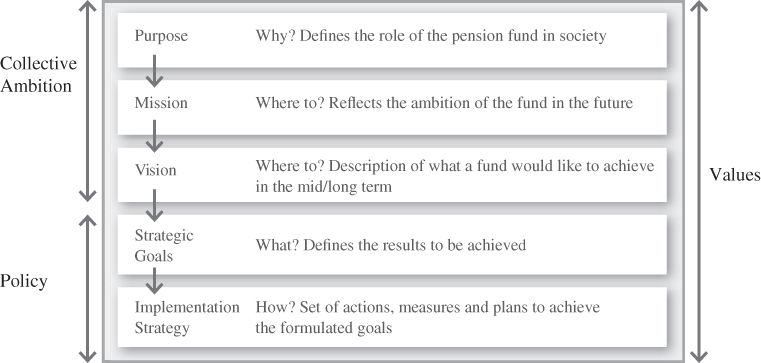

Exhibit 2.1 visualizes the six aforementioned steps of the strategy development process. One of the key messages of this chapter is that the way in which a fund invests may, and probably will, be influenced by its mission, vision and strategic goals. We will explore the formulation of purpose, mission, vision, and strategic objectives of the fund, as well as discuss how values are an integral part of the purpose and mission, and how they are vital for formulating the right strategic objectives. The main message is how the board can get the fund from where it is at the moment, to the place it wants it to be. Another key point is that defining and maintaining the purpose, mission, goals and strategy are important functions of the governing board—functions that cannot be delegated to staff or consultants.

EXHIBIT 2.1 The strategy development process.

An integral part of defining the mission and purpose is getting to grips with the actual activities of the fund. When quizzed, chances are that trustees will intuitively mention administration of pensions and investment of assets as the core of what constitutes a pension fund. While this is not wrong, it is also a narrow focus, and it helps for trustees to take a broader view. Understanding the generic functions of a pension fund will aid trustees in formulating its mission and strategy. For this reason, we have added a subsection to this chapter that considers these functions.

Values influence the mission, vision and strategy of a fund in a marked way, especially when investments are concerned. A pension fund has a specific DNA, which is related to its purpose and may reflect the industry it works for. For example, the pension fund for the Dutch airline KLM has a very different idea about the nature of risk from the typical investment professional—which is a reflection of what risk means in the airline industry. Another example is the Dutch health care pension fund PFZW, which does not invest in tobacco-related companies.

In order to be able to formulate effective strategic goals, the fund needs to understand where it currently stands and which forces will shape the future. This can be aided by carrying out a SWOT analysis to identify current Strengths & Weaknesses, and Opportunities & Threats from the external world. More information about this can be found in the Appendix.

THE FUNCTIONS OF A PENSION FUND

Developing a purpose and a mission requires in-depth knowledge of the true added value of pension fund organizations. After all, while it is true that consumers need pensions, it is not necessarily the case that they need pension funds. So, the question the board must ask itself is: What are the fund's key functions, those that matter most to the participants, and which add so much value that it makes sense to make those the basis for formulating the fund's purpose?

The activities of pension funds have changed and are still changing so rapidly that it is crucial to recognize and define the basic functions that remain stable, as opposed to the specific forms and organizations that will change with time and technology.1 The basic functions of a pension fund are:

- Pooling of contributions to reduce costs and gain access to more investable assets;

- Transforming assets in terms of risk, duration, denomination in order to earn risk premiums, and making sure that the level of investment risk is aligned with the participants' goals and risk appetite;

- Managing risk, to ensure that the fund invests in rewarded risks, and that unrewarded risks are mitigated or diversified;

- Acting as a delegated monitor on behalf of the members to make sure that the financial parties and transactions live up to their promise;

- Acting as a delegated monitor to support and guide the participants' financial choices;

- Transforming markets by helping savings and investments come together in an economy, creating financial returns as well as positive side effects.

The first function of a pension fund is pooling, which is one of its fundamental characteristics. In investment, economies of scale are advantageous: you pay less for the management and the running of a fund. A fund can thus afford more professional advice and gain access to a wider range of more specialized investment opportunities. Finally, pooling helps diversify participants' risks by widening the exposure to different assets and strategies. Pooling of funds from individuals provides a mechanism to facilitate large-scale indivisible undertakings, as well as the subdivision of shares in enterprises to facilitate diversification.

Pooling also provides access to new investment opportunities, improving the return/risk trade-off over time. Although costs have fallen in recent decades, transactions costs in securities markets, the bid–ask spread, and the minimum size of some investments still make it difficult for individuals to diversify optimally through direct securities holdings. One reason for this is that there are economies of scale in large transactions, partly based on the fixed costs involved. This means that individual investors do not have access to a wide range of investments, such as private equity, real estate, and infrastructure. Generally, the risk incurred if diversification is insufficient is not compensated by higher returns, because such risk can be diversified when one has the resources to do so.2 Historically, this meant that individuals either took excessive risks or were obliged to hold lower-yielding assets such as bank deposits. Pension funds can offer the opportunity to invest in large denomination and indivisible assets such as property, which are unavailable to small investors. Furthermore, they have the clout to negotiate lower transactions costs and custodial fees. Professional asset management costs are also shared among many participants and, as a consequence, are markedly reduced. The direct participation costs of acquiring information and knowledge needed to invest in a range of assets also decrease. In addition, the costs of undertaking complex risk trading and risk management are reduced (although the costs of monitoring the asset manager remain). All in all, pooling can help to maximize the pensions by making processes more efficient.

The second function of pension funds is transforming assets in terms of risk, duration or currency to earn risk premiums, while ensuring that the amount of investment risk is aligned with participants' goals and risk appetite.

Transforming assets is also a crucial function of a pension organization. Essentially, the board of a pension fund is entrusted with the task of transforming today's premiums into pension wealth and payouts in future decades. The consequences of these differing timescale requirements are resolved by asset transformation: the pension organization issues financial claims that in the future can be cashed in as pension payouts, which are more appealing to savers than holding on to the premiums or saving themselves. Pension funds must keep these pension contracts on their balance sheets until they expire: the contracts are generally non-marketable.

Any asset transformation can be unbundled into a combination of one or more of the following types of transformation: maturity, liquidity, denomination or country, and currency. Maturity transformation has the most far-reaching consequences for a pension fund and is usually defined as the asset-liability management (ALM) process. In macroeconomic terms, the maturity transformation relates to the difference in holding period preference between firms and individuals. An individual has compelling reasons not to offer their total amount of excess savings to firms. For example, they can have a precautionary motive for holding more money than required for current transactions in case of unforeseen events. In the case of a pension fund, the board has a responsibility to make sure that the assets are not underinvested, and carry the amount of risk that is in line with the longer-term ambition and associated risk appetite.

The third function of a pension fund is managing risk. It is plausible that, if a pension fund plans to transform risks, it only agrees to this if it expects to be rewarded. But the purchase of financial instruments for risk transformation, or entering into future financial commitments, can create unintended side effects. Investments in another country may carry a currency risk, as well as a country risk. A pension fund can opt to avoid unnecessary risk-taking, to share risks with participants, to transfer risks to other participants in the financial markets, or to absorb and direct the risk within the organization. Avoiding unnecessary risks requires good due diligence standards and/or portfolio diversification.3 For starters, a level of risk that is inconsistent with the desired characteristics or features of the fund needs to be avoided.

A pension fund can also shift the risks to other participants in the financial markets. For example, a pension fund that deals with payouts in the future is exposed to changes in interest rates. The risk can then be mitigated by means of derivatives such as interest rate swaps. If a pension fund gains no clear advantage from taking this risk, or if it is unable to absorb the risk, then this is an obvious step. Finally, the risks that the fund needs or wants to absorb remain. Participants with a customized pension scheme might have such specificity in their risks that the contract cannot easily be traded or sold to other market participants, and is therefore kept and managed on the balance sheet of the pension fund. One example is longevity risk. Investment risk can also be shared between different generations of participants to even out the peaks and troughs in investment returns and stabilize the pension outcomes of the participants.

The fourth function of a pension fund is being a delegated monitor in the financial markets on behalf of its participants. One problem that is faced by the individual participant paying pension premiums is the high cost of information collection. After the purchase of securities, participants need the progress of their investments to be monitored in a timely and comprehensive fashion. Failure to monitor their investments exposes them to agency costs, that is, the risk that the firm's owner or managers will take actions contrary to the promises made at the start or as stipulated in the covenants or agreements. This is especially relevant when the manager, as party to the financial transaction, has information the saver does not, or when one is an agent of the other, and when control and enforcement of contracts is costly.

One could view a pension fund as an information-sharing coalition and a delegated monitor who act on the depositor's behalf.4 Once the premiums are invested, further activities of the investments should be monitored, to at least ensure loan redemption. Any individual saver would have to devote a considerable amount of time and money in order to collect sufficient information to assess what the firm was undertaking, and would be better off if such monitoring were delegated and the transaction costs shared. The pension fund is the logical choice for delegation since it has more information than individuals about the firm invested in and can also put its experiences with other investments to good use. The pension fund can thus become an expert in the production of information, enabling it to sort out superior, rewarded risk from bad, unrewarded risk.

The fifth function is being a delegated monitor for the participants' financial choices. Anyone holding the responsibility for a pension scheme knows that employees need help. The responsibility for retirement funding is increasingly shifting either in part or almost entirely from the employer to the worker. Seeing that many employees may not be prepared for this undertaking, well-intentioned efforts to educate them have been under way. Plan sponsors and retirement plan service providers alike have spent vast amounts of time and money on participant education programs. As the literature shows, the rational capacity for making complex financial decisions about pensions, among other matters, is limited. Where this ends, people increasingly rely on mental shortcuts (or heuristics, as behavioral economists have called them). Unfortunately, this process leads to suboptimal retirement planning. A pension fund can act as a delegated monitor for the participants' financial choices, making them aware of when financial choices should be made, and providing information on how to make them. Depending on the board's or the regulator's vision, fiduciary duty could be extended to include helping participants to avoid behavioral biases, and promoting optimal choices.

Finally, the sixth function of a pension fund is to be a market participant. Pension funds have become sizeable players in the financial markets, a development that Peter Drucker signaled in the 1970s: they form large investment pools that can exercise influence on companies.5 From a macroeconomic viewpoint, a pension fund has a crucial role to play in transforming the savings of individuals into investments by companies, which in turn keeps the economy growing. Pension funds are financial intermediaries, similar to banks and insurance companies. Financial intermediaries bring together those economic agents with surplus funds who want to lend (invest), and those with a shortage of funds who want to borrow. In doing so, they offer the benefits of maturity and risk transformation. Financial intermediaries enjoy a related cost advantage in offering financial services, which not only enables them to make profit, but also raises the overall efficiency of the economy. As financial intermediaries, pension funds thus play a role in matching savings and investments in an efficient way, supporting the long-term welfare of the economy. In matching savings and investments, pension funds can target specific markets: they can select markets that are not functioning well, or they can create new ones. The former are markets where, for example, there is a lot of demand, but few suppliers. A pension fund could be well positioned to enter such a market due to its long-term horizon, increasing the supply/demand ratio in the sector and improving price-setting behavior.

All pension funds' purposes are, in one way or another, based on these functions. However, the focus and weighting differs widely, depending on the background of the industry the pension fund works in, the culture of its participants, and the culture of the board.

PURPOSE

A fundamental question for anyone becoming a trustee of a pension fund is: What is the purpose of the organization? This can be followed up by questions such as: Why is it here? What is its reason for being? What must it do to stay relevant?6

The answer to the first question may seem obvious—to make returns on investments in order to be able to pay out the promised pensions in decades to come. However, in these competitive times, this answer is not good enough. Earning investment returns is a necessary condition: without positive returns, a pension fund dwindles away and becomes insolvent over time. But this condition is not sufficient. Over time, pension funds have changed dramatically. In Western European countries, where they have increased enormously in size following decades of growth, funds are now being terminated, changed in scope, or merged with other funds. Sponsor covenants change, participants change and, by definition, pensions' needs therefore also change.

An integral part of defining purpose is thus getting to grips with what a pension fund actually does. Having a wider focus than simply administering pensions and investing assets will help with defining the purpose. The US pension provider TIAA, whose purpose is “to be the #1 provider of lifetime financial security for those who serve others”7 focuses on the delegated monitoring function, helping and assisting participants with information asymmetry. For the Norwegian Fund, the purpose is to “work to safeguard and build financial wealth for future generations.”8 This suggests a strong role for asset transformation and risk management—as well as for market transformation, given that future generations are named as the beneficiaries of its purpose. For another US provider, CalPERS, the purpose is to be “a trusted leader respected by our members and stakeholders for our integrity, innovation, and service.” Here, too, the delegated monitoring role is emphasized. In other words, understanding the function of a particular pension fund helps a board to formulate its purpose.

MISSION

There is a subtle difference between mission and purpose that trustees need to be aware of.9 A purpose is the fundamental reason for an organization's existence, an answer to the “why” question. A well-stated purpose is timeless, conceptual, and guiding in nature. Purposes are not a marketing slogan, nor should be made so. A mission is quite different. It is by definition achievable—to reach a certain target within a certain timeframe given specific resources. It is an answer to the “where to” question; or in what way you will fulfill the purpose. The board, working with its participants, has to define a mission to which all the members of the organization can commit. What might such a mission look like? We've chosen four examples:

- The London Pension Fund Authority's mission is “to provide an excellent cost-effective pensions service to meet the needs of our different customers.”10

- The South African Government Employees Fund's mission is “to ensure the sustainability of the fund; the efficient delivery of benefits; whilst empowering our beneficiaries through effective communication.”11

- TIAA's mission, “unchanged since 1918, is to serve those who serve others. Focusing primarily on institutions and individuals in the academic, medical, cultural, research and governmental communities, we offer solutions that help provide lifetime financial security and wellbeing on the best terms practicable, consistent with our nonprofit heritage.”12

- The Second AP Fund's mission is to maximize the long-term return on pension assets under management.13

Each of these missions has one or more elements making it possible to create tangible and strategic goals, whether in terms of the needs of the customers, the sustainability of the fund or—the most straightforward goal—the maximization of long-term returns. The task of the board of trustees is to position the organization in a robust way for different future environments—political, economic, environmental, and social—and with the slim resources available, to set up systems for monitoring trends and changes on a regular basis. Gathering and analyzing information related to future environments enables the board to develop informed decisions about future strategies.

An important element for trustees to consider in formulating the mission is whether they view their participants as investors or clients/customers. This distinction matters, because it guides the choices down the line: will the organization be modelled along the lines of a mutual fund, or more like an insurance company? Financial services such as life insurance and retirement annuities usually involve payments to the customer of specified amounts of money, contingent on the passage of time and events. The promised future services are liabilities of the firm, both economically and in an accounting sense. Since investors in the firm also hold its liabilities, the distinction between customers and investors is not always so clear. Merton14 argues that a distinction can be made:

- Customers who hold the intermediary's liabilities are characterized by their strong preference for the payoffs on their contracts being as insensitive as possible to the fortunes of the intermediary itself. Thus, a life insurance policy provides beneficiaries with a specified cash payment in the event of the insured party's death; a (nominal) pension policy provides regular cash payments from the predetermined retirement age onwards;

- By contrast, investors in the liabilities issued by an intermediary (e.g. its stocks, bonds, or mutual funds) understand that their returns may be affected by profits and losses. Their function is to allow the intermediary to better serve its customers by shifting the burden of risk-bearing and resource commitment from customers to investors. The investors expect to be compensated for this service with an appropriate return.

Formulating the mission of the fund requires knowledge of what the purpose of the fund is, as well as how the participants are viewed, so that the mission can be in line with them.

VALUES

Values are what support the purpose and mission, shape the culture, and reflect what the pension organization values. Values form the core of the identity of a fund. They can play an important role in binding the beneficiaries together and in the attraction of personnel. Pension leaders love to talk about values. They put them on the website, frame them, and proudly espouse them in media interviews. The notion of values has become so pervasive that it's hard to find any board that doesn't tout their importance.15 Formulating values makes sense for the pension fund on an organizational level, dealing with participants, and dealing with financial markets.

On an organizational level, boards that make the effort to articulate the values that are core to the participants and the pension fund can deal with potential inconsistencies that may arise at an early stage and in an open way. When pension funds articulate their values, many of them will probably share many of these. But chances are that when a combination of values stands out, or a particular value is accentuated, the board and organization has spent time considering this, helping the pension fund to differentiate itself from peers or competitors, often not just in product qualities, but also in cultural features.

When dealing with the pension fund's participants/customers, making values explicit matters. Values form the basis for the pension product, for example the way in which or the intensity with which environmental, social and governance (ESG) is integrated into the pension fund. In addition, defining values helps the pension fund align with its financial stakeholders: what sort of organizations and people would they like to be associated with, and what would they really like to avoid?

Pension funds almost always already have a set of values, even if they are not explicit. Therefore, it is important to discover these. Management author Jim Collins discusses the idea that organizational values cannot be “set” but should rather be unearthed.16 In other words, it would be a mistake to pick core values out of thin air and try to fit them into an organization. The average pension fund wants to “put the participant first,” or “be perceived as an organization with high integrity.” Formulating or adopting such statements without internalizing them may seem to be a short cut but it carries a long-term risk. A participant or employee could confront the boards with the values—especially if there is a disappointing outcome that is the result of explicit or implicit non-adherence to these same values by the board. And that is exactly what values are for: shaping the behavior of the fund. In this sense, values without consequences are not values at all.

Core values are neither “one size fits all” nor “best practices” in the pension industry. But you can hold the same core values as your competitors, as long as they are authentic to your organization, staff and participants. We have discussed why core values are important, as well as some strategies for defining core values. Below are several core values that have been developed by Government Pension Fund Global (GPFG)17 (the Norway fund):

- Excellence. We always strive to deliver: We are committed to a high degree of professionalism. Our investment philosophy based on diversification and specialization leads us to use various investment styles and strategies in a focused and consistent manner. Accuracy and thoroughness are at the core of our business culture;

- Integrity. We do the right thing: As individuals, we stand for honesty, integrity and loyalty. Recognizing the importance of reputation, we keep a modest profile as representatives of our organization. We have a culture characterized by openness, tolerance and accountability;

- Innovation. We encourage new ideas: In order to succeed we are willing to take risks and we have a corporate culture that embraces change. We encourage different approaches and views. Creativity and flexibility are vital for developing new investment opportunities and adapting to changing market environments;

- Team spirit. We work together as one team: As colleagues, we respect and support each other. We believe that cooperation and interaction creates a strong organization. We never underestimate the value of enthusiasm and a good sense of humor.

When a pension fund is in the process of defining its values, it has to overcome some challenges. It has to consider multiple sets of values, e.g. the values within the organization of the board, of participants, and of the investors; and determine whether there is tension between them and how this can be solved.

Participants share a set of values depending on the nature and homogeneity of the workforce. For several sectors, the unearthing of values is a straightforward process. Participants working in the healthcare sector are almost bound to share a desire to improve people's health and would like to see this reflected in the values of the fund. Similarly, participants in the metal sector's pension scheme find their working conditions important, and a teacher's pension fund would probably name values that embed the prospect of education and equal opportunities. Theoretically, the values of the fund should reflect those of participants. The board on the other hand needs to consider additional values:

- It has to consider that the participant base might well be too diverse to distill common values, in which case the board has to settle for the greatest common denominator;

- The board can interpret its fiduciary duty more broadly and is therefore inclined to incorporate values like paternalism: listening very closely to the participants' needs and wishes but resisting the temptation to follow up on all of them;

- As already discussed, some boards of trustees are also responsible for the pension delivery organization and have intimate knowledge of the values that exist there. There can be quite a discrepancy between what the investors feel is a good way of investing and the values of the members. This often leads to tension, for example when integrating ESG into the investment process. It is important to understand and tackle this tension.

Conceptually, the board's challenge can be pictured in Exhibit 2.2. The challenge is to manage the degree of overlap in a transparent way. The task of the board is to act in the best interests of the participants, but a situation may arise in which the participants feel that the board does not consider their values sufficiently. For example, it may be that participants have a very critical attitude towards investing in fossil fuel companies even though it could be in their best interests. This will lead to tension, which is not easily relieved. Other examples of “productive tension” could be the remuneration of the investment management organization, or the choice of publicly visible and controversial investments. The pursuit of ESG goals and investments that have little bearing on the characteristics and concerns of the participants is an example of too little alignment.

EXHIBIT 2.2 The different levels of alignment between board and participants.

Formulating a set of values leads to two follow-up questions that need to be considered: do they really guide choices; and what can the board do to make them credible and felt throughout the organization?

Values should guide choice, and at times this choice has a cost. In an article in the Harvard Business Review, management expert Patrick Lencioni writes, “If you're not willing to accept the pain real values incur, don't bother going to the trouble of formulating a values statement.”18 When values are formulated, the follow-up question could therefore be: “What do these values cost you?” This cost could be monetary or non-monetary, but more importantly, it implies that you have to be explicit about them. This has for example been the center of a debate ever since the late 1990s when funds focused on formulating values around participants and the community. From the 1990s onwards, trustees had begun integrating the value of socially responsible investing into the investment process. The difficult question was whether this value was something that could and should be framed as a choice that cost something. In this case, the choice of financial instruments is determined by the values that participants have—for example, would they agree with their pensions being invested in the weapons industry? Some funds framed it as an investment trade-off: would customers prefer an investment strategy that excluded certain investments and on paper led to a potentially suboptimal investment result, versus an optimal trade-off that would include some investments that disagreed with the customer's values?

VISION

The vision clarifies how, given the current situation and any future changes, the fund aims to become or remain fit for purpose in the future. A good vision should be stretched, but realistic: if it is too far from the current position of the fund, the people involved will lose faith and the vision will not be realized. There are two dimensions involved when formulating a vision. First, the amount of time you allow yourself to realize the vision. A good rolling horizon is 5–10 years. You need a certain horizon to be able to change in a strategic way, but on the other hand, who can or wants to look further than 10 years ahead? Second, the level of aspiration. In terms of this book, your vision could be that you want to increase your level of investment excellence over the course of the next five years. Normally, people will enjoy such aspirations as long as they are attainable.

STRATEGIC GOALS

The next step in the strategic formulation process requires the board to identify the performance targets for the clearly stated objectives. Strategy has many definitions, but generally involves setting goals, determining actions to achieve these goals, and mobilizing resources to execute the actions. A strategy describes how the means can be used to achieve the ends. Strategy can be planned (intended) or can be observed as a pattern of activity (emergent) as the organization adapts to its environment or competes. Intended objectives may include market position or position relative to the competition, quality of financial pension product, improved customer services, corporate expansion of the pension delivery organization, advances in technology, and increasing assets under management.

In order to ensure success, strategic objectives must be communicated to all the pension fund's employees and stakeholders. All members of the organization must be made aware of their role in the process and how their efforts contribute to meeting the organization's objectives. Additionally, members of the organization should have their own set of objectives and performance targets for their individual roles. When formulating strategic goals with one's sights on investing, we could differentiate between:

- Investment and financial goals. Along the lines of improving long-term pension and health benefit sustainability;

- Organizational goals. How to foster a high performance, risk-intelligent, cost-effective organization that adapts; how to maintain its strengths and address its weaknesses;

- Collective goals. There are many important collective goals for pension funds, such as good regulation, good corporate governance and disclosure, which will only be realized by collective action. These are goals to enhance the long-term efficiency and effectiveness of the pension fund and financial markets. Engaging in these activities is a choice that pension funds must make. The size of the fund, its ability to influence outcomes with the management of investments, and the pressure from stakeholders (government or lobby groups) determine the fund's ability to engage in these kinds of activities. We suggest that if possible it is worth contributing, to avoid becoming a free-rider, which may be a cost-efficient position, but also a mentally impoverished one to be in.

The full scope of the strategic goals of a pension fund is much wider, but this is beyond the scope of this book. Examples of this scope include how to communicate to participants, or how to apply the newest technology in fund administration, etc. We encourage trustees to delve deeper into this matter. Understanding a fund's function and purpose lays the foundation for the mission. By making your values and vision explicit, you enable an easier and more efficient path to realize your strategic goals, all in order to fulfil the fund's purpose.