Foreword to the 2013 Paperback Edition

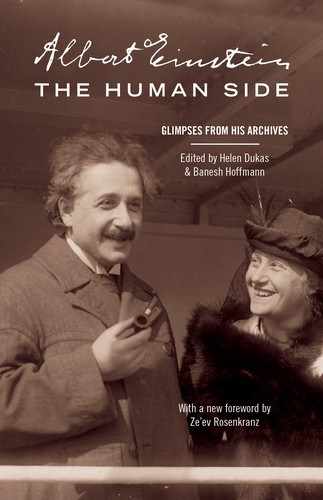

THIS little gem of a book, edited by Einstein’s longtime secretary Helen Dukas and his erstwhile collaborator Banesh Hoffmann, was originally published in mid-March 1979 to coincide with the celebration of that year’s centenary of the birth of Albert Einstein. Presenting over 140 excerpts from the great physicist’s writings and correspondence, the editors provide explanatory introductions to each individual passage. As described in their preface, the editors’ goal for the publication was to offer “a seemingly rambling sightseeing journey whose cumulative effect, we hope, will be a deeper and richer understanding of Einstein the man” (p. 4).

Undoubtedly, the editors succeeded in their enterprise. This book is a true labor of love. The excerpts from Einstein’s papers were selected with utmost care and consideration. Helen Dukas, who, like Einstein, hailed from Swabia in southern Germany, began working as his secretary in 1928 and continued to serve in that capacity until his death in April 1955. During her tenure, she was eventually adopted as a member of the Einstein household, fiercely defending the world-renowned celebrity from intrusive journalists and curious Princeton sightseers. After his passing, Dukas was the natural person to become the first archivist of Einstein’s personal papers and she also served as co-trustee of the Einstein Estate. The British-born mathematician and physicist Banesh Hoffmann joined the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton in 1935, and in 1938, Hoffmann collaborated with Einstein and Polish-born physicist Leopold Infeld on a classic paper on the problem of motion in general relativity. Dukas and Hoffmann had collaborated in the early 1970s on a highly successful biography of Einstein—Albert Einstein, Creator and Rebel—so they were ideally suited to produce the unique publication before us.

This book’s genesis is a story worth telling. One year prior to the 1979 Einstein centenary, former director of Princeton University Press, Herbert S. Bailey, contacted Banesh Hoffmann and asked him whether he was interested “in working on a small centennial volume containing excerpts from and translations of Einstein letters and the like of a humanistic nature.”1 Thus, the intention to focus on Einstein’s “human side,” his humanity, and his humanism was apparent from the very inception of the project. In regard to the structure of the book, Hoffmann informed Bailey that he preferred “a seemingly loose structure that would be somewhat analogous to that of a movement of a symphony, with an interplay of various themes that recur and expand in different keys.”2 Subsequently, Helen Dukas was called upon to co-edit the book with Hoffmann. There followed an intense exchange between the two in which they discussed issues of selection, placement, and translation.

The loose structure that Hoffmann had envisaged was clearly implemented by the editors. Rereading the book after several years, I was struck by how it resembled a jazz symphony in numerous suites. Major themes like Nazism, morality, philosophy, the nature of science, art, and religion, and the essence of being human weave their way through the volume, emerging, disappearing, and resurfacing again at different junctures. In their preface, the editors call the sections in the book “sequences.” There are actually twelve such sequences. Some of them are clearly dedicated to Einstein’s correspondence with specific individuals such as Queen Elizabeth of the Belgians or his long-time friend Otto Juliusberger. Others illuminate a defined topic such as psychoanalysis or music. What combines them is Einstein’s humanity which shines through many of the selected passages.

Hoffmann surmised there was no way of knowing whether a book would turn out to be popular but “I think we are well aware that this one might catch the public fancy.”3 And catch the public fancy it did. The first edition of 10,000 copies almost sold out completely in bookstores after merely two weeks at the end of March 1979. The book has never been out of print since it was originally published which clearly reflects its great popularity and continued success.

My professional association with Albert Einstein began twenty-five years ago when I was hired to work at the Einstein Archives in Jerusalem. As its curator, I benefitted greatly from the inspiring work Helen Dukas had carried out maintaining, organizing, and expanding Einstein’s personal papers from the mid-1950s to the early 1980s. As mentioned in the publisher’s preface, Dukas had compiled lists of “special items” throughout the many years she was the Archives’ loyal custodian. Reading this book and familiarizing myself with Dukas’ lists was of immense help to me in preparing exhibitions and publications for the Einstein Archives, and the lists proved particularly useful for me as curator. The passages included in this volume are the mere tip of the iceberg of the many items Dukas compiled. This book and Dukas’ lists also undoubtedly shaped my initial perception of Einstein. Most of all, I was struck by his deep humanism, his talented use of the German language, and his wry and witty sense of humor. Since then, naturally, my perception of Einstein has become far more complex. Nowadays, I am particularly fascinated by the internal contradictions in his personality, by the variegations in his points of view on many political and social issues, and by the juxtaposition between Einstein the private individual, Einstein the public figure, and Einstein the mythic icon.

Both as a private individual and as a public figure, Einstein’s humanism was expressed in its purest form by defining what it meant for him to be human. The excerpts included in this volume provide us with some of the answers to that question. Intriguingly, Einstein himself claimed there was no link between his scientific work and his pursuit of social and political ideals (p. 18). This statement is in tune with his defining the study of the laws of nature as a means to flee from the “merely personal.”4 However, as much as he wanted to evade dealing with the vicissitudes of life, he was acutely aware that he could not fully do so. Moreover, it became a concern of utmost importance to him to express his ideals for humanity and to define the guiding principles for human existence. In numerous instances throughout this volume, Einstein makes it quite clear that the most important factor in our humanity is our morality and ethical stance. To him, morality was an even more significant issue than the study of science (p. 70). This belief clearly grew stronger as he aged. Thus, he came to define being human in its noblest sense as our being moral and ethical creatures. A major part of that humanism was the belief in the universality of all human beings. And to uphold that universality, Einstein firmly believed that the individual needed to be protected by tolerance from imperilment by the state. On the lighter side, apart from his far-sweeping visions for humanity, this book also provides us with odd glimpses of how Einstein perceived himself. This volume reveals that Einstein could perceive himself both as “an old gypsy” (p. 32) and as “quite handsome” (p. 44). He also saw himself both as a “Jewish saint” (p. 63) and as “a loner” (p. 80).

If we relied solely on this book, we would form the impression that at times Einstein despaired only of certain individuals and societies (e.g., Nazi Germany), yet not of humanity in its entirety. However, that judgment would be a hasty one. Other sources reveal that Einstein often swayed between optimism and pessimism, hope and disillusionment, admiration and revulsion, in regard to the human race. Shortly after the outbreak of World War I, he confided to a close friend that he viewed humans as a “sorry species” for whom he experienced “a mixture of pity and revulsion.”5 A year later his distress in regard to the human race had persisted and deepened: “It seems that people always require a chimera for whose sake they can hate each other; it used to be religious faith, now it is the state.”6 The world war confirmed his disillusionment with humanity: “Reason is not a means for binding earthly humans together for any lengthy period of time.”7 And following many years of turbulence in interwar Germany, he remarked that “[i]t is people who make me seasick—not the sea.”8

The dichotomy established by Einstein between his scientific and his human side may have also motivated the editors to produce this book. One wonders why those involved in the project thought there was a need for a book which would emphasize Einstein’s human side. That motivation is not really made explicit in their correspondence. Did Dukas and Hoffmann surmise that Einstein, synonymous with 20th-century science, had become a suprahuman icon, who had transcended the realm of mere mortals? That is certainly a possibility. Were they concerned that in the few decades since his death his numerous political and social activities and interests had been consigned to oblivion by the general public? That is also possible. Both editors were intimately connected to Einstein and intensely protective of his public persona. Thus, their concept (and implementation) of revealing Einstein’s “human side” is presumably markedly different from how this would be handled nowadays. In our current era, the very phrase “human side” would be far more likely to pertain to Einstein’s private life—his relationship with his parents and with his sister Maja. It would cast light on his two marriages—to fellow student Mileva Marić and to his cousin Elsa. It would reveal his role as a father to his born-out-of-wedlock daughter Lieserl and to his two sons Hans Albert and Eduard and as a step-father to Elsa’s daughters Ilse and Margot. It would also touch on his many friendships and his numerous extra-marital affairs.

I think it is a fair statement that this volume also does not explore the limits of Einstein’s humanism. He was, to some extent, an elitist, supporting the idea to bestow “power into the hands of capable and well-meaning persons” (p. 88). His humanism was also curtailed by his belief that not all humans were of equal value: towards the end of World War I, he appealed to a brilliant young German scientist who was gung-ho to go off and fight for his country to stay at home and suggested that “this post of yours out there … be filled by an unimaginative average person of the type that come twelve to the dozen.”9 The limits to Einstein’s humanism could also extend to the inhabitants of entire nations and continents. In 1917, he stated that the Europeans do not deserve anything better than that their civilization will go under.10 And on his extensive trip to the Far East in 1922–23, Einstein fell in love with Japan and its culture. He used superlatives to express his admiration for the country and his Japanese hosts. In stark contrast, however, he repeatedly referred in his travel diary to the Chinese he encountered as being “lethargic” and “dense.”11 Einstein even went as far as occasionally employing pejorative biological terminology to describe his opponents in institutional conflicts. In his clash over the Hebrew University of Jerusalem he referred to some of its administrators as “downright vermin” and called the university “a bug-infested house.”12 Another clear limit to Einstein’s humanism was the manner in which he sometimes would refer to members of the opposite sex. There are numerous instances in which he expressed opinions which we would today undoubtedly term misogynistic. Claiming that we should not have the same expectations of women as we have of men due to “certain restrictive parts of a woman’s constitution that were given her by Nature,” Einstein could only muster lukewarm support for women obtaining a university education. According to his first biographer, he even went so far as to state that “[i]t is conceivable that Nature may have created a sex without brains!”13 Most poignantly, when his younger son Eduard was growing up and struggling with numerous ailments, Einstein stated that he “will never become a fully developed human being” and wondered whether “it would not be better were he to depart from the world before he really came to know life.” Einstein blamed the genetic disposition Eduard had inherited mainly on the child’s mother but also to a certain extent on Einstein himself.14

Should we then, in light of these less than pleasant examples of the limits to Einstein’s humanism, simply dismiss and discount his high-minded attempts to establish ethics and morality as the guiding principles of human existence? I do not believe so. To my mind, both his lofty ideals and his at times less than lofty views on specific individuals and social groups testify to the very humanness of Albert Einstein. Like him, we all live in the perilous no man’s land between our ideals and our prejudices. They are both the most authentic expressions of our “human side.”

Ze’ev Rosenkranz

1. Hoffmann to Bailey, 11 March 1978, Einstein Archives. I would like to express my gratitude to Barbara Wolff of the Einstein Archives for making this correspondence available to me.

2. Hoffmann to Bailey, 27 May 1978, Einstein Archives.

3. ibid.

4. Einstein, Autobiographical Notes, La Salle and Chicago: Open Court, 1979, p. 5.

5. Einstein to Paul Ehrenfest, 19 August 1914, The Collected Papers of Albert Einstein (CPAE), Vol. 8, ed. by Robert Schulmann et al. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1998, Doc. 34.

6. Einstein to Hendrik A. Lorentz, 2 August 1915, CPAE, Vol. 8, Doc. 103.

7. Einstein to Walter Dällenbach, 27 September 1919, CPAE, Vol. 9, ed. by Diana Kormos Buchwald et al. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004, Doc. 112.

8. Einstein to the Schering-Kahlbaum Co., 28 November 1930, Einstein Archives 48 663.

9. Einstein to Otto H. Warburg, 23 March 1918, CPAE, Vol. 8, Doc. 491.

10. Einstein to Heinrich Zangger, 13 February 1917, CPAE, Vol. 8, 297a in Vol. 10.

11. Einstein, Travel Diary to Japan, Palestine and Spain, 6 October 1922–12 March 1923, CPAE, Vol. 13, ed. by Diana Kormos Buchwald et al, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012, Doc. 379.

12. Einstein to Leo Kohn, 17 March 1928 [CZA/L12/147II].

13. Einstein quoted in Alexander Moszkowski, Einstein the Searcher. His Work Explained from Dialogues with Einstein. New York: E.P. Dutton & Co., 1922, pp. 79–80.

14. Einstein to Michele Besso, 9 March 1917, CPAE, Vol. 8, Doc. 306.