8

Scriptwriting as a pedagogy has been dominated for the past three decades by an obsession with three-act structure. A parallel perception that actually seeks a deeper structure, the journey of the hero, sources from the writings of Joseph Campbell. Before the dominance of these two approaches, Aristotle and his theatrical descendants focused upon the rising action of conflict organized into a narrative. The primary struggle of the protagonist and antagonist was the baseline of every story.

In the midst of all these activities applied to the understanding of screen-writing, genre was either a reference to style such as the visual stylization of a film noir or a particular narrative story form such as the gangster film that lent itself to visual stylization. The only other reference to genre was within literary theory. Northrop Frye in his seminal work, The Anatomy of Criticism, refers to large general categories of genre—comedy, tragedy, and romance. Within these general categories, he describes particular motifs and tropes, specific to the larger categories.

In this chapter, we suggest that genre is the missing link in the pedagogy of screenwriting. We also suggest that every film narrative fits into one genre or another and that there are two general categories of genre. The first, the classical genre, fits in the three-act structure, whereas the second, voice-oriented genres, does not. The latter grouping is discussed in Chapter 13 .

With regard to the classical genre, we’d like to suggest that the contemporary pedagogy of screenwriting is incomplete without consideration of genre. Genre is the meta-structure of the screenplay. It organizes premise, character, and structure. As the specific genre has its own character arc and dramatic arc, it is impossible to move the screenplay forward effectively until a determination of the genre of the narrative is made. It is the genre decision that tells the writer whether the character arc is positive or negative and whether enough plot is being used in the narrative’s dramatic arc. Until a genre is chosen, the writer can only stumble forward in the writing process. Choosing a genre, in short, is a critical decision that will enable the writer to progress his or her screenplay. Understanding genre enables the writer to choose the genre appropriate to his or her narrative.

The Progression of Screenwriting

A screenplay usually begins with a character, a situation, or an incident. A particular place or time period may equally incite the beginning of a screenplay.

Depending on the writer’s experience, a series of tropes may provide a general structure to the idea. Examples of such tropes might be the following:

- My first serious relationship.

- An adventure that turns bad.

- The workplace has its own rules.

- Avoid commitment at all costs.

- Good intentions are never enough.

- Ambition helps one and hurts many.

- Leaving home.

- My father the disappointment.

- Technology is a threat.

- I win the lottery.

From the above list, the writer decides whether he or she wants to explore a life lesson, apply a coming of age or loss of innocence matrix, focus on character, or focus on plot. The exploration of an ethical challenge or the nature of morality in a particular character, time, or place also avails to the writer the capacity to grow his initial idea.

The next narrative step is to populate the story with dramatically suitable characters and of course to decide upon a beginning, middle, and an end for the story.

Further informing the writer about the narrative is the answer to a series of self-reflective questions.

Why does this story grab my imagination?

What does it mean?

What would I like to say in this story?

The answers to these questions will move the story away from stereotype and hopefully toward creative uniqueness.

The next sequence in the screenplay’s evolution requires consideration of the nature of an audience’s relationship with the main character of the screenplay.

Is the main character likeable, sympathetic, and empathic?

How can the writer enhance these qualities in the main character?

Is there a structural intervention (the plot) that will strengthen the identification of the audience with the main character?

How can other characters including the antagonist be deployed to strengthen the audience’s relationship with the main character?

In relation to the story progression, another set of questions come into play.

Does the main character change in the course of the narrative?

Is there enough change to justify the anticipated length of the screenplay?

How is that change affected?

How substantial is a device, surprise, deployed in the screenplay?

Does that surprise enhance the rising action within the structure of the screen story?

The next consideration can be described as the positioning of the main character in the narrative. Ideally the main character should be positioned in the middle of the narrative. A double check on positioning is to pose the questions who is helping the main character and who is opposing the main character? Here too balance is important. If no one opposes the main character, does this flatten the dramatic properties of the screen story to this point? To turn this issue on its head, is there a premise operating for the main character in the screen story? The premise sometimes referred to as the spine or the central conflict of the screen story needs to be present throughout the screenplay.

One working definition of the premise is to consider two opposing choices for the main character. Love or money for Rose in James Cameron’s Titanic (1997); ongoing dishonor or regained honor for Frank Galvin in Sidney Lumet’s The Verdict (1983); selfishness or humanness for C.C. Baxter in Billy Wilder’s The Apartment (1959). A useful organization of the character population around the main character is to see one group representing option 1 of the premise and the balance representing option 2.

No dialogue has been written. A tone for the screenplay has not yet been determined.

It is at this fork in the narrative road that particular pedagogical strategies will focus on sharpening structure or defining the voice of the writer and planting it deep in the narrative or simply focusing on telling the story in as effective and engaging a way as possible. Any of these approaches will move the screenplay ahead possibly even to a reasonable conclusion. Our suggestion however is that the narrative journey will be faster and stronger if the matrix of genre is applied at this point.

The Benefits of Genre

There is no single genre that is meant for a particular story. Rather it is more useful to see genre as a series of potential pathways each taking the viewer on a different journey. There’s no one right journey. Each genre shapes the narrative differently. Knowing about genre will however help the writer make the choice best suited to tell the story the writer is trying to tell.

At its core, every genre positions a character in the story differently. Genre choice also influences the resolution of the story, the deployment of plot versus character in the story, and reflects a tone that enables the audience to believe in the narrative’s outcome. This must all sound terribly self-serving about genre’s importance in narrative. Genre is important; genre is the critical decision in the writing of the screenplay. It’s time to explain why.

The Character Arc

At the beginning of the screenplay, we join a main character at a critical moment in his/her life. For dramatic purposes, let’s call that critical moment a crisis. In the course of the screenplay, we are going to follow that main character and watch him/her adapt or change to meet the crisis. By the resolution of the screenplay, the main character will have changed either for the better or for the worse, depending on the genre. That change is enabled by a relationship or relationships. If the relationship is extremely central, we might call the character pushing for the change a transformational character. If that character is negative or powerful in their opposition to the main character and his goal, that character is the antagonist. Plot can also put pressure on the main character and force adaptation or worse. The character arc then is a reflection of how the character under duress (usually the main character) changes from the beginning to the end of the screenplay. Genre choice influences the critical moment, the beginning, the end, the nature of the character population, positive and negative, the degree of character change, and the credibility of that degree of change. Let’s turn to each of these points in the character arc and its shape, in turn.

The Critical Moment

An arrogant scientist decides to experiment upon himself resulting in a behavioral shift with self-destructive consequences in Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1933), a horror film. A self-defeating actor can never get an acting job, because he knows more than the director, in Tootsie (1985), a situation comedy. An unworldly naïf is asked to save the world from evil in The Lord of the Rings (2001), an action-adventure. A relentless and famous detective has an almost fatal heart attack while pursuing a killer in Blood Work (2002) a police story. An uneducated but ambitious young man arrives in the East to take up his rich uncle’s offer of a job, if he comes East, in A Place in the Sun (1951), a melodrama.

In a sense, the action of the main character in the critical moment of the screenplay points us, the audience to a particular resolution appropriate to the genre. The arrogant risk-taking of Henry Jekyll at the beginning of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde makes his later destruction very much in keeping with genre expectations.

In Tootsie, Michael’s arrogance as an actor who knows more than the directors auditioning him makes his decision to audition as a woman who becomes a very successful actor as a woman, very much in line with the clash of values, the source of comedy in the situation comedy.

Frodo’s naivety and goodness make him a less than likely superhero who can best the super-villains amassed against him and his allies in the action-adventure film The Lord of the Rings. It also makes Frodo appealing in a genre permeated by wish fulfillment rather than realism.

Here we come to an important point about genre. Blood Work and A Place in the Sun, a Police Story and a Melodrama, are genres whose credibility is based upon how realistic they are. Consequently their crisis points, where we enter these stories, has to be equally realistic. Frodo on the other hand is not a realistic main character at all. As action-adventure is all about wish fulfillment, the journey of Frodo from naïf (even his physical size is anti-heroic) to super-hero is at best a metaphor for the notion that goodness will always trump evil in the world, at best a wish if we look at the history of the past century.

Turning to the dark turn of events in Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, we see the cautionary tale in full flight. Fly too high and you will die. Accept the natural order or die. In the horror film, the nightmare dominates the form. Humans beware.

Resolution

Just as the critical moment in its relationship to the main character’s goal and nature will differ from one genre to another, so too will the resolution.

An insurance salesman flirts inappropriately with a client’s wife in Double Indemnity (1943). Whether he does so out of boredom or out of desperation, this critical moment starts him on the journey that will lead to his own destruction. Destruction of the main character is the resolution of the character’s arc in film noir.

The arc in situation comedy is far more hopeful. In The Apartment, the main character also works for a large insurance company. As we meet him, he is lending his apartment for a night to an insurance executive. He does so in the hope that the executive will enable his promotion within the company. His behavior is as ignoble as the main character in Double Indemnity. Nevertheless his fate is quite different. He chooses to become a better person, a more humane person at resolution. This positive ending is in keeping with the situation comedy just as the dark ending is the resolution audiences expect from film noir.

The resolution is more extreme in the action-adventure. Indiana Jones, a risk-taking archeologist, survives death at the critical moment of Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981). By its resolution, he has evaded hordes of Nazis, outfoxed an equally-clever archeologist, and essentially rescued mankind by preventing the Nazis and said rival archeologist from possessing the ancient all- powerful Ark of the Covenant. In short, Indiana Jones has become a superhero.

Of course this is an absurd outcome but very much in keeping with action-adventure film, a story form brimming with wish-fulfillment (as opposed to realism). The key point here is that it’s the genre choice that will determine whether a resolution is realistic, the outcome of wish, or the outcome of a nightmare.

The Nature of the Character Population

In general terms, the character population will be extreme in genres of wish-fulfillment such as the action-adventure film and in genres of the nightmare such as the horror film and the film noir. In the more realistic genres such as the melodrama and the situation comedy, the character population will be realistic, as recognizable as a neighbor, a friend, or family.

More specifically, the character population is determined by their service to the premise. Another variable that will determine the character population is the tone of the film. The lighter the characters are, the more enabling they are for the main character. The more intense dark or powerful they are, the greater the threat to the main character and his/her goal.

To illustrate genre differences in character population, we turn to four films, two thrillers, a melodrama, and a situation comedy. Because all are realistic genres, the character populations have to be credible and realistic.

Steven Frear’s Dirty Pretty Things (2001), written by Steven Knight, is the story of Okwe (Chiwetel Ejiofor), an illegal immigrant in London from Nigeria, trying to make his way. He works with West Indians, Yugoslavs, and Turks; his best friend is Chinese, and his primary employer is Spanish. The character population with the exception of two British immigrant officials is immigrants, strangers in this strange white land, London. The plot surrounds the exploitation of immigrants. They sell their vital organs for British passports. Formerly a doctor in Nigeria, Okwe because of his illegal status is doubly exploited as a doctor and as an illegal.

Aside from making the point that all these immigrant groups, legal awaiting legality or illegal, all live on the margins. All are also either victims or perpetrators in this world of immigrants. Senay (Audrey Tatou) is a Turkish national, not allowed to work but working as a cleaner in a hotel, to make her way. Juliette (Sophie Okonedo) is a black prostitute. Guo Yi (Benedict Wong) is a legal immigrant working in a morgue as an attendant, to make his way. All share status and support with Okwe.

Jan (Sergi Lopez), manager of the hotel where Okwe, Juliette, and Senay work, is the antagonist who runs the sale of illegal organs business. He is Spanish, powerful, and the clear antagonist for Okwe and the other illegals. But he is not alone. A sweatshop employer elicits sexual favors from Senay to keep a job. British immigration officials hunt down Senay relentlessly, as if she were an animal rather than a woman from Turkey seeking to improve her life.

The point here is that the character population aligns with the premise (does an illegal have to act illegally to become legal?) around the issue of personal behavior vis-à-vis others, ethical or exploitative. And in keeping with a central motif of the thriller—can an ordinary person (Okwe) in unusual circumstances (illegal status) overcome a powerful antagonist whose goal is to use him up?

Guillaume-Canet’s Tell No One (2006), a thriller, is based on American Harlan Coben’s novel. The screenplay is by Canet and Philippe Lefebre. The critical moment is the murder of Alexandre Beck’s (Francois Cluzet) wife Margot (Marie-Josee Croze). Eight years later, he has not recovered from the loss but finds himself the prime suspect in her murder. Unless he learns why/ how/if she died, he will suffer the fate of the accused and convicted. The narrative concerns itself with the consequences of his becoming the prime suspect and the unfolding of the search for the real killer if his wife is indeed dead. She is not and he is not.

The character population is principally three groups—the family and friends of Margot and Alexandre. This is widely interpreted to include a gangster, Bruno, whose son is a patient of Alexandre. The second group is the investigators—police and lawyers who are working to prove or disprove Alexander’s guilt. The third group is the actual perpetrators of the attempt to kill Margot and now to kill Alexandre. They represent the true harmers in the narrative.

Tell No One has an unusually large character population. Canet weaves it tight by including “guilty” people among the friends or helpers. Margot herself, her father (a police captain), Alexandre’s sister, Margot’s best friend have participated in deceiving the main character Alexandre. But each has deceived out of love for the main character or to protect him.

The antagonist, Senator Neuville (Jean Rochefort) has enlisted criminals to act on his behalf and to punish Margot for the death of his son, years earlier. The son, a sexual predator and violent character, was killed because of his violence toward Margot years earlier. Alexandre learns of his history only in Act III.

The character population in Tell No One is trying to either protect or harm Margot. Alexandre just happens to be the husband. In her absence (death or disappearance), he becomes the target. To survive, he needs to understand and escape the rush to judgment by the police and the rush to murder on the part of the senator’s cohorts. Protecting or harming becomes the rationale for the character population in Tell No One .

What is notable about the character population in both the thrillers is the presence of a powerful antagonist who essentially drives the plot. A second feature of the character population is that even those characters who are helpers to the main character play a key role in endangering the main character. Margot in Tell No One and Senay in Dirty Pretty Things as they face the ultimate threat to their lives force the main character to save them, thereby posing the greatest level of threat to the main character.

This immediately differentiates them from the situation we find in the Melodrama. After the Wedding (2006), Susanne Bier’s film, has no true antagonist and only a modest plot.

Jacob (Mads Mikkelson) is a childcare worker in an orphanage in India. He is called back to Denmark to secure desperately needed funding for the orphanage. The benefactor Jurgen (Rolf Lassgard) invites Jacob to the wedding of his daughter. There Jacob meets his former girlfriend once more, now Jurgen’s wife, and at the wedding, the bride announces that Jurgen is not her real father.

In short order, Jacob discovers he is the girl’s real father. What will he do? His situation is complicated when he learns Jurgen is dying of cancer. The premise for Jacob is to stay in Denmark or to return to India. The first option represents responsibility and the second idealism.

The character population in After the Wedding flesh out the stay or go options. In Denmark, Jacob’s daughter, his former girlfriend, and Jurgen are important, as is his daughter’s husband. In India, the primary character is Pramod, a young boy who Jacob has raised from infancy.

Although the daughter’s husband Christian misbehaves, there is no real antagonist here. Jacob’s struggle is an internal struggle. In this sense, he is his own antagonist. Because there is very little plot, the character population is much smaller than in the thriller.

Lucas Moodysson’s Together (2000) is a situation comedy set in a commune in 1975 Stockholm. Goran, the de facto leader of the commune, has a sex-obsessed girlfriend whose quest for orgasm trumps her relationship with Goran. He believes in open relationships in principle. He is after all an open-minded male. The narrative opens when his conventional sister, Elisabeth, and her two children leave her physically abusive alcoholic husband Rolf. Can Elisabeth change for the better by living in the commune? Can the commune survive its internal stresses and contradictions? This is the narrative as well as the source of the comedy in Together .

The character population of Together divides among the membership of the collective and those outside it. Inside the collective, the characters are deeply unhappy. Goran’s girlfriend Lena is always betraying him. Lasse’s ex-wife Anna lives in the collective now as a lesbian. He has not recovered from the breakup. Klas, a gay man, longs for Lasse. Eric, a banker’s son, angrily embraces doctrinaire Marxism. None of these characters are happy hippies.

Among the conventional characters, Elisabeth and Rolf and their two children struggle with the consequences of alcoholism in their family. Both sets of characters are struggling with the everyday problems of life essentially relational breakdown and human experiments in different belief systems to help them cope with those problems.

Moodysson uses a larger than average character population to drive home his belief that unhappiness is more often than not the human condition. There is no plot here, and there are no real antagonists. In this sense, the title of the film is ironic. In the film, we at last see the enemy and discover that the enemy is us. Here the large character population fleshes out Moodysson’s premise in a mixture of funny and sad. In this particular genre, the character population flesh out the premise and realistically struggle with each other and themselves.

The degree of character change in the screen story also varies with genre. More specifically, if we look at Okwe’s change in Dirty Pretty Things and Alexandre’s change in Tell No One, both thrillers, we notice that by the resolution both have survived and are happy. But on a deeper level, both are the same people they were when we met them at the critical moment. This is typical of character change in the thriller.

In the case of Elisabeth and Goran in Together, a situation comedy, and of Jacob in After the Wedding, the character change that takes place is altogether deeper. The values of the character and their belief systems have faced a challenge, and in each case, those beliefs are either confirmed or modified. Notable is that in each case, the character has changed. Whether something has been lost or gained, the depth of challenge and change for Elisabeth, Goran, and Jacob is significant and deep. It’s also emotionally wrenching. This too is more typical of character change in the melodrama and in the situation comedy. And we speak here only of character change among three realist genres. Character change is far greater in genres of wish fulfillment and of the nightmare. Because those genres are more extreme in narrative as well as character, they require a degree of belief suspension that simply doesn’t operate in realistic genres. The point here is that genre choice dictates all the characteristics of the character arc mentioned here, and they differ from genre to genre. Deciding on the genre of a screenplay consequently is one of the more important decisions the writer will make.

The Dramatic Arc

The romantic comedy is dominated by progress of a particular relationship. Boy meets girl, or boy meets boy, or girl meets girl. After these two very opposite natures meet, we follow the course of the relationship. The resolution accentuates that relationship’s success. The dramatic arc of the romantic comedy is the course of the relationship.

Every genre has a distinct dramatic arc that differentiates one genre from another. The dramatic arc in the sports film is the career of the main character. The dramatic arc of the gangster film is also a record of the career of the gangster, but it has a rise and fall shape ending in the destruction of the gangster, whereas the sports film focuses primarily on the rise.

The dramatic arc of the police story follows a crime-investigation-apprehension shape. The dramatic arc of film noir follows the progress of a relationship, but it’s far from the romantic comedy. It’s a bad relationship that will lead to the destruction of the main character. A subplot is the crime that proves the main character’s love; it’s the nail in the main character’s coffin. The dramatic arc of the thriller is a chase that tends to work out well for the main character. The dramatic arc of the horror film is a chase as well, but its outcome is not a good one for the main character.

The dramatic arc of the melodrama and the situation comedy are shaped by a particular sort of power struggle. In both, the main character is a powerless person seeking power from the power structure. The main character may be a young person in an adult world, a woman in a man’s world, a minority character in a majority world, a gay person in a heterosexual world. The positioning of the main character and the goal of empowerment characterize the dramatic arc of the melodrama and the situation comedy. In the situation comedy, the main character tends to succeed in their goal; the result is more mixed in the melodrama.

The dramatic arc expands in its ambition in genres of wish fulfillment. It’s nothing less than good and evil in the action-adventure with good embodied in the main character and his or her cohorts and evil embodied in the antagonist and his or her cohorts. The struggle takes on a moral character in the Western and a more particular struggle between humanity and technology in the science fiction film. In all cases, there is an epic quality to the nature of the struggle in the dramatic arc. Clearly all these stories of wish fulfillment are intended to make their audiences feel better just as genres of the nightmare in their particular dramatic arcs are intended to unsettle their audiences. Here, the key is that the dramatic arc of each genre will differ from that of other genres.

What else needs to be said is that writers will often layer in a melodrama dramatic arc to emotionalize the screen story and to reach out more deeply to its audience. To be more specific, the main character in Lawrence of Arabia, T.E. Lawrence, is a bastard son of a lord in the class-driven upper ranks of the British army. He feels himself to be an outsider. The power he acquires is as the leader—mastermind of the Arab revolt during World War I. That war in the deserts of the Middle East is the plot of Lawrence of Arabia .

Similarly Clarice is positioned as a powerless character in Silence of the Lambs. She acquires power in this police story by killing Buffalo Bill. Lisbeth Salander is a powerless marginal person in the thriller, Girl with the Dragon Tattoo. She acquires power by revenging herself against men who have abused her and by helping Mikael Blomkvist in the plot to find other abusers/killers of women in the Vanger family. In each of these films whether a war epic, a police story, or a thriller, the dramatic arc has been elevated by the addition of a melodrama frame for the main character. Think of it as the deployment of two dramatic arcs in a single screen story. In each case, the melodrama layer has deepened the impact of these films on their audiences.

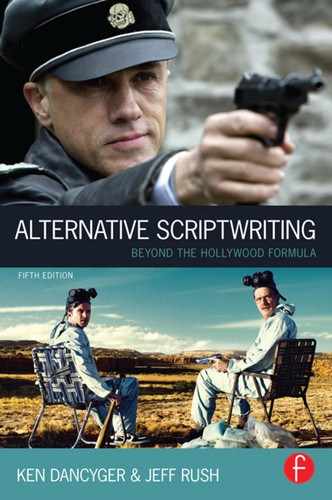

This same principle is what is operating in the great television successes of the past decade. From The Sopranos to Breaking Bad to Downton Abbey to Deadwood, the use of deeper melodrama dramatic arcs for a number of the characters have complemented the gangster film arc in The Sopranos, the heist film arc in Breaking Bad, and the morality tale arc in Deadwood, making these films deeper experiences in the gangster film, the heist film and the Western, respectively.

But each of them begins in a genre. Writers can take the narratives deeper or remain within the classic genre frame. The richness of each however begins with an appreciation and application of a specific genre. That’s the why of it.