8

FINANCIALIZATION AND INVESTMENT: A SURVEY OF THE EMPIRICAL LITERATURE

Leila E. Davis

Middlebury CollegeEconomics

1. Introduction

The 2008 financial crisis, beginning in the USA and spreading globally, drew the financial systems of advanced economies to the forefront of public awareness, and led to a surge of research on the size and role of the financial sectors of advanced economies. Importantly, however, this surge of attention comes on the coattails of a secular expansion in finance – across countries and by a range of measures – since the 1970s. In the USA, for which the most detailed data are available, financial sector growth is evident as a share of GDP, employment, total profits or outstanding financial assets (Krippner, 2005; Greenwood and Scharfstein, 2013; Montecino et al., 2016). Similar trends occurred outside the USA as well: Philippon and Reshef (2013) document growth in the income share of finance across a set of developed economies (the UK, the Netherlands, the USA, Japan and Canada), and Jordà et al. (2016) measure an international expansion in private credit relative to income in the second half of the twentieth century.

This growth in the size and scope of modern finance is increasingly summarized as financialization. Broadly, financialization is perhaps most commonly defined as the ‘increasing role of financial motives, financial markets, financial actors and financial institutions in the operation of domestic and international economies’ (Epstein, 2005, p. 3).1 Importantly, this expansion of finance is reflected not only in the size and scope of the financial sector, but also in the behaviour of nonfinancial actors and in nonfinancial outcomes (see Krippner (2005) for an early elaboration of this point). Thus, while precise definitions vary across analyses, the shared premise underlying accounts of financialization is that this expansion of finance is a critical feature of the post-1980 USA economy, with substantive implications for foundational economic relationships (Palley, 2007; Sawyer, 2013; Fine and Saad-Filho, 2014; Epstein, 2015).

A substantial branch of the literature on financialization analyses, in particular, the relationship between financialization and fixed investment. Striking shifts in the balance sheet structure of nonfinancial corporations (NFCs) point to the financialization of traditionally nonfinancial firms, and suggest links between various aspects of financialization and investment. These trends are most fully documented for the USA (see Davis, 2016), where a shift in portfolio composition towards financial assets (Crotty, 2005) is, for instance, often used to suggest that financial investments increasingly replace – or ‘crowd out’ – fixed investment. Concurrently, firm balance sheets reflect changes in the structure of external finance, including growth in both indebtedness and own-stock repurchases, particularly among large firms (Davis, 2016). There is, correspondingly, an expansion in financial profits earned by nonfinancial firms (Krippner, 2005), and also in payments by NFCs to financial markets (Orhangazi, 2008a).

An increasingly complex relationship between NFCs and the financial sector is, also, evident in that some large NFCs, arguably, increasingly resemble financial firms (Froud et al., 2006), and also in a growing ‘portfolio conception’ of the firm, wherein NFCs are viewed as bundles of assets rather than capital-accumulating enterprises (Crotty, 2005). These changes in firm behaviour have come with a slowdown in capital accumulation, despite rising profitability, pointing to an ‘investment-profit puzzle’ in which a declining share of profits is reinvested in physical capital (Stockhammer, 2005; van Treeck, 2008, 2009a; Gutiérrez and Philippon, 2016). As is discussed below, this puzzle may reflect, for instance, growing shareholder orientation, wherein NFCs increasingly focus on financial indicators of performance over firm growth and fixed investment (Stockhammer, 2004; Davis, 2017).

Building on these stylized facts, a growing literature finds that features of financialization are systematically related to investment. However, there remains lack of consensus on the primary channels through which this relationship occurs, and even on the direction of the relationship. An influential first wave of empirical research suggests a decisively negative effect of financialization on investment (Stockhammer, 2004; Demir, 2007, 2009a,2009a; Orhangazi, 2008a,b; van Treeck, 2008); this relationship is, similarly, reflected in a body of theoretical literature (Stockhammer, 2004, 2005; van Treeck, 2008, 2009a; Dallery, 2009). Conversely, however, Boyer (2000) considers conditions for ‘finance-led’ growth, and Aglietta and Breton (2001) emphasize the role of asset price inflations in capital accumulation. Skott and Ryoo (2008), furthermore, highlight sensitivity to the theoretical specification of the investment function (Harrodian or Kaleckian). Davis (2017) points to varied relationships between different features of financialization and firm investment rates in the USA, including a positive correlation between financial assets and investment, but a negative effect of shareholder orientation. Kliman and Williams (2014) contend, in contrast, that falling accumulation rates in the USA are wholly unrelated to financialization.

This paper surveys this literature on financialization and investment to take stock of where we are and what remains to be done. To understand the range of conclusions reached in this literature it is, first, important to recognize that the definition of financialization remains nebulous and often varies substantially across papers. This variance in definition has both advantages and disadvantages. On the one hand, financialization summarizes a broad, wide-reaching process of structural change, and there is no a priori reason to expect all aspects of this phenomenon affect investment analogously. A range of empirical indicators, thus, has the advantage of capturing different aspects of financialization. On the other hand, the term ‘financialization’ is often applied differentially across analyses despite an often-implicit pretense that the same phenomenon is analysed. As such, it is increasingly unclear what is meant when one concludes that ‘financialization’ does or does not depress investment.2 More specifically, within countries different empirical measures are used to draw different conclusions about financialization and investment, without clear reference to distinctions between the indicators used. Across countries, conclusions from one country – for example, regarding shareholder ideology in the USA – are sometimes also applied to other countries despite vastly different institutional settings. One contribution of this survey is, thus, a delineation of distinctions between studies that claim to otherwise study the same thing: ‘financialization’ and investment.

To understand the conclusions reached in this literature it is instructive to divide the literature into two parts. The first emphasizes financial flow-based indicators of financialization and changes in the relative stocks of fixed and financial assets, debt and equity on firm balance sheets. In the USA, for example, Orhangazi (2008a) finds that both increased financial payments made by NFCs and increased financial profits earned by NFCs are negatively associated with fixed investment, particularly among large firms. This analysis captures systematic negative relationships between fixed investment and growing income flows between NFCs and the financial sector. Notably, these results have been widely interpreted to imply that financial asset acquisitions ‘crowd out’ physical investment. In presenting this part of the literature, I emphasize, in particular, this possibility of crowding out. Importantly, more recent analyses do not find conclusive evidence of crowding out (Kliman and Williams, 2014; Davis, 2017) and, more generally, the literature emphasizing financial flows is characterized by variability in conclusions. This variability reflects, in part, differences in sample definitions and/or scope of analysis, but also points to a more general limitation of this branch of the literature.

In particular, while these financial flow-based indicators of financialization capture important changes in where profits accrue in the post-1980 USA economy they also raise further questions. These flows stem from firm decisions to acquire financial assets, or to borrow, repurchase stock or pay dividends. Thus, this expansion of financial flows, as well as changes in the structure of firm balance sheets from which these flows derive, raises the question of what has changed in NFC decision making – for example, in managerial objectives – such that a break in firm behaviour occurs specifically in the post-1980 period. Put differently, why has firm financial behaviour changed after 1980 such that investment rates have slowed? These determinants have important implications for understanding the relationship between financialization and investment. For example, the implication of higher leverage (with, correspondingly, higher interest payments) for fixed investment differs if firms borrow to exploit profitable fixed investment opportunities, to repurchase shares or to fund banking divisions (Davis, 2017). As the literature on financialization and investment expands, significant scope remains for identifying specific behavioural mechanisms underlying the stylized facts that summarize financialization, and for delineating differences in these behavioural stories across countries.

The second branch of the literature analyses shareholder orientation, which is the most fully developed behavioural explanation linking financialization to investment to date. Since the 1980s, the ‘maximization of shareholder value’ has become an increasingly dominant corporate governance ideology, particularly among USA firms (Lazonick and O'Sullivan, 2000; Fligstein, 1990; Davis, 2009). Shareholder ideology is, in particular, linked to changes in corporate strategy from one aiming to ‘retain and reinvest’ to one aiming to ‘downsize and distribute’ (Lazonick and O'Sullivan, 2000). Arising from agency theory, shareholder value ideology contends that closer alignment of managerial interests with those of shareholders – for instance, via stock-based managerial compensation – improves corporate performance (Jensen, 1986; Jensen and Murphy, 1990). The literature on financialization and investment, however, establishes evidence that shareholder orientation has adverse implications for firm investment, emphasizing both increased managerial attention to financial performance indicators like earnings per share (Stockhammer, 2004; Davis, 2017) and corporate myopia (Stout, 2012).

This paper, accordingly, surveys the literature on financialization and investment by introducing these two branches of the literature. The paper is organized as follows: Section 2 introduces definitions of financialization in the literature on financialization and investment. Sections 3 and 4 introduce the two main strands of the literature: increased flows between NFCs and finance, and shareholder orientation. Section 3, also, suggests limitations of analysing financialization and investment exclusively on the basis of financial flows and points to the importance of a behavioural understanding of financialization and investment. Section 5 concludes and suggests avenues for future research. Finally, a point about scope. The empirical literature on financialization and investment has, to date, focused disproportionately on the USA, reflecting in part the size and international dominance of USA finance and also that key mechanisms, like those related to shareholder orientation, are closely linked to country-specific institutions defining the degree of shareholder power. This survey follows this emphasis in the existing literature, but also introduces the literature exploring the relationship between financialization and investment in developing countries, which has focused largely on financial flows (Section 3).

2. Defining Financialization

All analyses of financialization that emphasize NFCs and investment underscore either an increasingly complex relationship between NFCs and financial markets, or stronger NFC orientation to financial performance targets. Orhangazi (2008a), for example, uses the concept quite broadly to ‘designate the changes that have taken place in the relationship between the nonfinancial corporate sector and financial markets’ (p. 3). Somewhat more narrowly, Lazonick (2013) emphasizes the financialization of corporate resource allocation, wherein companies are increasingly evaluated by measures like earnings per share, rather than by the goods and services produced.

However, specific definitions, and their empirical operationalizations, differ substantially. This variance in definitions – and also, more generally, the fact that financialization is an ambiguously defined term – has been widely noted (for example, Stockhammer, 2004, p. 721; Orhangazi, 2008a, p. 863; Skott and Ryoo, 2008, p. 827; Fine, 2013; Fiebiger, 2016). Nonetheless, there is little attention on the extent to which these conceptualizations of financialization do/do not overlap, or the degree to which different definitions explain different results in the literature. Accordingly, an important starting point for surveying the literature on financialization and investment is recognition and discussion of the definitions of financialization across the existing literature.

To highlight the main approaches to financialization in the literature on investment, Table 1 summarizes empirical definitions of financialization across this literature, focusing on empirical papers that analyse the financialization of the nonfinancial corporate sector and/or investment. In addition to econometric analyses of investment, Table 1 includes papers that do not explicitly investigate investment behaviour, but establish empirical evidence of financialization linked to the nonfinancial corporate sector (for example, Krippner (2005), which measures the financial incomes of nonfinancial firms). The summary in Table 1 calls attention to a heterogeneous set of changes in firm financial behaviour, including increased shareholder payouts and/or dividend payments, the rate of return gap between fixed and financial assets, and financially derived incomes. This range of definitions captures, on the one hand, that – as financialization reflects a broad process of structural change – it is inherently multi-dimensional. Different analyses should, therefore, emphasize different features of this broad process and, similarly, different features of financialization may affect investment behaviour differently. However, ambiguity in the definition of financialization also obfuscates distinctions underlying analyses of financialization and investment. In particular, varied empirical operationalizations of financialization imply that, as the literature on financialization and investment grows, it is increasingly unclear what is meant when one concludes that ‘financialization’ does/does not depress physical investment.

Table 1 Empirical Definitions of Financialization (Analyses of Financialization of Nonfinancial Corporations and/or Investment)

| Empirical Indicator of Financialization | Location and Time Frame of Analysis | Level of Analysis | |

| A. The asset side of the balance sheet & financial sources of income | |||

| Stockhammer (2004) | Interest and dividend income of the nonfinancial business sector (rentiers’ income), relative to sectoral value added. |

Germany (1963–1990) France (1979–1997); UK (1971–1996); USA (1963–1997) |

Aggregate |

| Krippner (2005, 2011) | Interest, dividends and realized capital gains on investments (portfolio income), relative to corporate cash flow. | USA (1950–2001) | Aggregate |

| Orhangazi (2008a)a | Financial profits (interest income and equity in net earnings), relative to the capital stock. | USA (1973–2003) | Firm |

| Demir (2009b) | Rate of return on fixed assets less the rate of return on financial assets (i.e. the gap between returns on fixed and financial assets)b |

Argentina (1992:2–2001:2) Mexico (1990:2–2003:2) Turkey (1993:1–2003:2) |

Firm |

| Kliman and Williams (2014) | Financial assets (‘portfolio investment’)c | USA (1947–2007) | Aggregate |

| Seo et al. (2016) | Financial assets | Korea (1990–2010) | Aggregate |

| Davis (2017) | Total financial assets (relative to total assets), and the financial profit rate (interest and dividend income, relative to financial assets). | USA (1971–2014) | Firm |

| B. The liability side of the balance sheet & financial payments | |||

| Orhangazi (2008a)a | Financial payments (interest payments, dividend payments, and stock buybacks) relative to the capital stock. | USA (1973–2003) | Firm |

| van Treeck (2008) | Interest payments and dividend payments, both relative to the capital stock. | USA (1965–2004) | Aggregate |

| Onaran et al. (2011) | Net dividends, net interest and miscellaneous payments (rentiers’ income), relative to GDP. | USA (1962:q2–2007:q4) | Aggregate |

| Kliman and Williams (2014) | Dividend paymentsa | USA (1947–2007) | Aggregate |

| De Souza and Epstein (2014) | Net lending of nonfinancial corporate sector (or reduction in net use of external finance) |

USA (1947–2011); UK (1991–2010); France (1971–2011); Netherlands (1980–2011); Germany (1995–2011); Switzerland (1995–2011) |

Aggregate |

| Seo et al. (2016) | Dividend payments | Korea (1990–2010) | Aggregate |

| C. Shareholder value orientation | |||

| Stockhammer (2004) | Interest and dividend income of the nonfinancial business sector (rentiers’ income), relative to sectoral value added. |

Germany (1963–1990) France (1979–1997); UK (1971–1996); USA (1963–1997) |

Aggregate |

| van Treeck (2008) | Dividend payments | USA (1965–2004) | Aggregate |

| Orhangazi (2008a)a | Financial profits (interest income, dividend income) and financial payments (interest payments, dividend payments and stock buybacks), each relative to the capital stock. | USA (1973–2003) | Firm |

| Mason (2015) | Corporate borrowing and shareholder payouts (dividend payments and stock repurchases) | USA (1971–2012) | Aggregate |

| Davis (2017) | Average yearly industry-level stock repurchases (relative to equity). | USA (1971–2014) | Firm |

aOrhangazi (2008b) defines similar indicators on the basis of aggregate data.

bThe empirical definition of financial profits varies by country. For Argentina, financial profits are measured as interest income; for Mexico, financial profits are defined by net foreign exchange losses (gains), financial income (loss, and income (loss) from other financial operations; for Turkey, financial profits are defined as interest income and other income from other operations (p. 323). See also Demir (2007).

cThe text of Kliman and Williams (2014) also reiterates a range of other possible indicators of financialization. The main text, however, most often refers to financialization in the context of ‘rising dividend payments and the growth of corporations’ portfolio investment’ (p. 67).

In addition to this heterogeneity, however, Table 1 also identifies three main approaches to measuring ‘financialization’. These approaches correspond to the main outline of this survey: the first two feature increased financial flows between NFCs and finance (Section 3), and the third emphasizes shareholder orientation (Section 4). In particular, one set of analyses emphasizes growth in the financial incomes of traditionally non-financial firms (Stockhammer, 2004; Krippner, 2005; Demir, 2007, 2009b; Orhangazi 2008a,b; Davis, 2017). Growth in holdings of financial assets (i.e. the stock of assets from which these financial profits derive) is, also, included in this category (see also Dögüs, 2016). A second set of papers highlights increased payments made to finance by nonfinancial businesses, including interest, dividends and/or stock repurchases (Orhangazi 2008a; van Treeck, 2008; Onaran et al., 2011; de Souza and Epstein, 2014; Kliman and Williams, 2014). Finally, a third set of studies aims to operationalize shareholder value orientation (Stockhammer, 2004; van Treeck, 2008; Orhangazi, 2008a; Mason, 2015; Davis, 2017); in some cases, these papers, also, equate financialization with shareholder value ideology. Note that Table 1 lists papers fitting into more than one of these three categories multiple times: for instance, Orhangazi (2008a) emphasizes aspects of financialization linked both to financial incomes and payments to finance.

At least two additional points fall out of this categorization. First, even within each subset of the literature there are meaningful differences in measures of financialization. For example, higher financial payments have been captured empirically by payments to creditors and shareholders (Orhangazi, 2008a); by dividend payments to shareholders (van Treeck, 2008); and by all shareholder payouts, including both dividends and repurchases (Mason, 2015). In the post-1980 USA these measures are qualitatively different: shareholder orientation is associated with a growing prioritization of shareholder payouts, and own-stock repurchases are consistent with the increasing prioritization of capital gains over long-term dividend growth (see Section 4). Second, the delineation between empirical indicators employed and the mechanisms that are emphasized is sometimes unclear. For instance, Stockhammer (2004), Demir (2007, 2009b) and Orhangazi (2008a,b) exploit, at least in part, similar indicators (an increase in financial profits/rentiers’ income). Across these papers, however, the interpretation of the relationship between this measure of financialization and investment differs in important ways: Demir suggests financial profits crowd out fixed investment; Stockhammer uses the indicator to explain changes in firm behaviour associated with shareholder value; and Orhangazi's interpretation incorporates elements of both.

In addition to the categories outlined in Table 1, two additional branches of the literature on financialization and NFCs can be identified. One emphasizes links between the international reorganization of production, global value chains and the financialization of USA firms (Milberg, 2008; Milberg and Winkler, 2010, 2013). Milberg (2008), for example, analyses an ‘offshoring-financialization’ linkage, wherein offshoring fails to generate dynamic gains in investment by USA firms because these firms increasingly purchase financial assets and repurchase stock, rather than (domestically) reinvesting higher profits. Fiebiger (2016), also, links financialization and ‘de-nationalization’ in production, pointing to a range of measurement issues arising in the context of expanded USA production abroad after the mid-1990s. Outside of these contributions, however, this branch of the literature remains relatively sparse, in part due to data limitations and, in particular, explicit links to investment remain to be drawn.

A final theme emphasizes volatility and uncertainty, most often in the context of financial liberalization in developing and/or emerging market economies (Demir, 2009a,2009c; Akkemik and Özen, 2014; Seo et al., 2016). Building on evidence that financial liberalization both increases macroeconomic uncertainty and increases firms’ opportunities to invest in financial assets, uncertainty and/or risk become key parameters mediating firms’ portfolio allocation decisions between illiquid capital investments and liquid financial investments (Demir, 2009b). Rising firm-level volatility also characterizes the USA experience over this period (Comin and Philippon, 2005); linking volatility and growth in firm financial asset holdings in the post-1970 USA, Davis (2017) introduces firm volatility into the investment function and captures a negative link between volatility and investment. The role of uncertainty and risk in mediating the relationship between financialization and investment remains, however, relatively underexplored. Existing evidence raises further questions about how firms’ portfolio decisions may be differentially impacted by idiosyncratic risk and macro-level uncertainty, as well as about differences in the responsiveness of portfolio allocation decisions to risk in developed and developing economies.

3. Firm Financial Behaviour and Investment

The first branch of the literature on financialization and investment analyses the consequences of secular shifts in the balance sheet structure of NFCs, and the financial flows derived from these balance sheet stocks, for fixed investment. This literature draws primarily on Keynesian and Minskian approaches, which emphasize the importance of financial factors in investment (Eichner and Kregel, 1975; Minsky, 1975; Skott, 1989; Crotty, 1990, 1992; Lavoie, 2014). The role of financial factors in investment is, however, also widely accepted outside of the post-Keynesian literature (see, for example, Fazzari et al., 1988).

This section follows the first two panels of Table 1 to introduce the main results in this segment of the existing literature. In each case, I first introduce the trends in the asset and liability sides of firms’ balance sheets, respectively, that motivate analyses of financialization and investment. This literature highlights systematic relationships between changes in firm financial behaviour and investment, but also raises questions for further analysis, not least because the existing empirical literature points to sometimes-contradictory conclusions. In some cases, different results undoubtedly stem at least in part from different sample definitions and empirical methods; instances of these differences are pointed to in the discussion below. In other cases, different conclusions reflect different empirical approaches to defining financialization. Finally, and most importantly from a conceptual perspective, these differences motivate a behavioural approach to financialization and investment in future research that, in particular, emphasizes determinants underlying changes in firm financial behaviour.

3.1 Financial Profitability and Financial Asset Holdings

3.1.1 Post-1970 Trends in Portfolio Composition and Profitability

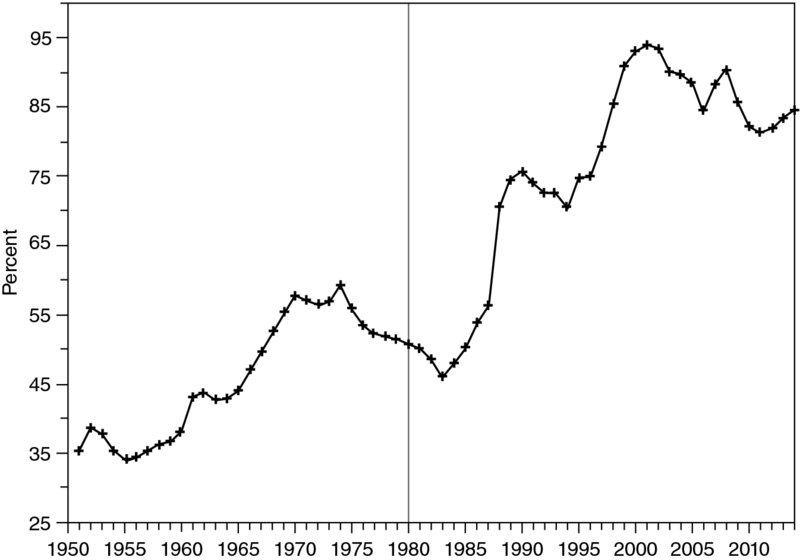

A first striking feature of the post-1970 period in the USA economy is secular growth in the financial asset holdings of the nonfinancial corporate sector. This portfolio shift is highlighted in Figure 1, which plots financial assets and fixed capital, each relative to sales between 1950 and 2014, in the median across USA NFCs. While both series are largely stable through the 1950s and 1960s, they diverge in the early 1980s; the ratio of financial assets to sales, in particular, climbs from approximately 25% in 1980 to 47.4% of sales in 2014. The firm-level decomposition in Davis (2016) indicates that this portfolio shift holds across firm size and industry, as well as when financial assets are normalized by other measures of firm size.

Figure 1. Fixed Capital and Financial Assets Relative to Sales (Yearly Median Across Nonfinancial Corporations).

Source: Compustat, author's calculations (reproduced from Davis, 2016).

Notes: The two series plot the across-firm yearly median of financial assets and fixed capital, each relative to firm-level sales between 1950 and 2014. Ratios are winsorized to account for outliers. Financial assets are defined as the sum of cash and short-term investments, current receivables, other current assets (less inventories) and ‘other’ investments and advances (Compustat items 1, 2, 68, 31, 32 and 69). The capital stock is defined as property, plant and equipment (Compustat item 141). Sales are drawn from Compustat item 12. The vertical line denotes 1980 to highlight the beginning of the period emphasized in the discussion.

Together with this expansion in financial asset holdings comes growth in NFC incomes from financial sources. Krippner (2005, 2011) documents growth in portfolio income (interest, dividends and realized capital gains) relative to corporate cash flow earned by the nonfinancial corporate sector beginning in the 1970s and accelerating during the 1980s; this ratio signals a growing ‘extent to which non-financial firms derive revenues from financial investments as opposed to productive activities’ (2005, p. 182). Orhangazi (2008a,b), similarly, highlights growth in NFCs’ financial incomes, documenting an increase in two specific sources of financial income – interest and dividend income – relative to internal funds after the early 1970s. Dumenil and Levy (2004a) document growth in French nonfinancial firms’ holdings of other firms’ stock, as well as corresponding growth in dividend income, thereby also accentuating ‘strong increases in financial revenues in relation to revenues linked to the main activity of firms’ (p. 118). Furthermore, while rentiers’ income most commonly refers to economy-wide private-sector financial profits (clearly a broader concept than the financial profits of nonfinancial firms), growth in rentiers’ income corroborates these trends, and also extends the evidence to a set of Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) economies (Epstein and Power, 2003; Epstein and Jayadev, 2005; Dünhaupt, 2012). Rising financial incomes are also identified as a key manifestation of financialization in developing and emerging market economies, where financial liberalization has been followed by pressure to maintain high interest rates to sustain capital inflows (Demir, 2009a,2009b; Bonizzi, 2013).

These financial cash flows should, furthermore, be distinguished from financial profit rates. As such, growth in financial asset holdings and financial incomes, also, raises the question of the rate of return earned on financial assets. Dumenil and Levy (2004b) find that financial incomes – net interest, dividends, holding gains on assets and profits due to the devaluation of liabilities by inflation – increase overall profit rates in the USA between the early 1950s and 1982. After 1982, however, the gap between measures of the profit rate that do/do not incorporate financial factors largely disappears. Accordingly, financial relations most significantly improve USA firms’ profitability at the beginning of firms’ portfolio reallocation towards financial assets. This point is corroborated by the firm-level financial profit rates in Davis (2016), defined as firm-level interest and dividend earnings relative to financial assets (p. 135). This financial profit rate is positive for the full post-1970 period, but does not trend upwards with the exception of a small increase in large firms’ financial profitability in the early 2000s (a period Dumenil and Levy's data does not include). Notably, the absence of a significant trend in financial profit rates is consistent with the fact that a large share of financial asset growth among USA firms is in highly liquid assets, yielding interest but not necessarily high returns (Davis, 2016).

It is, finally, important to note data limitations involved in measuring the total financial profits of nonfinancial firms. Total financial profits of NFCs include total interest income, dividend income (both from subsidiaries and affiliates, and other dividends) and capital gains (Krippner, 2005). Capital gains, in particular, include cash flows from net foreign exchange gains/losses, gains/losses from marketable securities and other short-term investments and gains/losses from sales of shares in other companies (Demir, 2009b). However, reporting requirements make it difficult to uniquely identify each of these income streams, such that total financial profits are difficult to document.

Thus, while Orhangazi (2008a), for example, documents a clear upward trend in two well-defined categories of financial income (interest and dividend income) at the sector level, this trend underestimates total financial profits both because it excludes other sources of financial income like capital gains (see Orhangazi, 2008a, p. 877), and because the Flow of Funds nets out within-USA within-sector holdings, such that dividends earned from stock of other USA NFCs are not included in dividends received (see Dumenil and Levy, 2004b, p. 102). Measurement issues arise in the firm-level data for the USA as well, in which it is neither possible to obtain a measure of capital gains nor to clearly identify all sources of financially derived income (see again Orhangazi, 2008a, p. 877; Davis, 2017). Notably, to measure capital gains at the sector level, Krippner (2005, 2011) uses (non-publicly available) Internal Revenue Service (IRS) data.3 It is, accordingly, important to take note of differences in the definitions of financial profits across analyses.

3.1.2 Do Financial Assets ‘Crowd Out’ Capital Investment?

An influential set of empirical papers emphasize this expansion in financial assets and incomes, and consider whether the portfolio shift towards financial assets has come at the expense of physical investment. This channel has come to be known as the ‘crowding out’ thesis (for this usage see, as examples, Teixeira and Rotta, 2012, p. 454; van der Zwan, 2014, p. 14). This possibility is first analysed by Demir (2007, 2009a) and Orhangazi (2008a,b) who hypothesize that an increase in financial profits generates a portfolio reallocation towards financial investments that, in turn, reduces investment rates. Following Tobin (1965), if the yields of two categories of assets differ, these assets are held in proportions depending on their relative yields (p. 768); imperfections in financial markets and risk-diversification strategies ensure that nonzero quantities of both assets are held. Therefore, when internal funds are limited, there is ‘substitutability of real and financial assets in portfolio balances’ (Demir, 2009a, p. 314), such that ‘increased financial investments could have a negative effect [on real investment] by crowding out real investment’ (Orhangazi, 2008a, p. 865).4

This hypothesis is consistent with a growing ‘portfolio view of investment’ (Demir, 2009b, p. 316), wherein nonfinancial firms with increased access to financial markets exploit the availability of relatively quick and high financial returns. All else equal, an increase in the rate of return on financial assets effectively increases the ‘hurdle’ rate NFCs must expect to earn on fixed capital in order to allocate funds towards fixed assets, thereby reducing fixed investment rates as firms allocate (limited) funds towards financial investments (Demir, 2009b). While Demir emphasizes emerging markets, Crotty (2005), similarly, argues in the USA case that a key dimension of financialization is a ‘shift in the beliefs and behavior of financial agents…. to a “financial” conception [of the nonfinancial firm] in which the NFC is seen as a “portfolio” of liquid subunits’ (p. 88; see, similarly, Fligstein, 1990). Uncertainty, furthermore, implies firms may prefer investment in liquid, reversible financial assets over irreversible fixed capital when financial assets offer higher or even comparable rates of return (Crotty, 1990; Tornell, 1990; Demir, 2009a). This point is important: an excess of financial over real rates of return is not necessary for financial profitability to reduce investment rates; instead, a decline in the gap between real and financial profitability or an increase in uncertainty may be sufficient to depress investment.

This hypothesis is most often tested empirically by introducing financial cash flows or financial profit rates into estimations of the investment function.5 The inclusion of financial profits into investment specifications is common across the literature on financialization and investment, whether directly via total financial earnings (Stockhammer, 2004; Orhangazi, 2008a,b; Demir, 2009c; Onaran et al., 2011; Seo et al., 2016; Tori and Onaran, 2017), the differential between rates of return on real and financial assets (Demir, 2007, 2009b) or the financial profit rate (Davis, 2017). Note that while Stockhammer's (2004) theoretical model concerns shareholder orientation (discussed in Section 4), the main empirical proxy for financialization – the interest and dividend income of the nonfinancial business sector – is closely tied to this section of the literature.

The empirical results in each of these papers point to a negative relationship between financial income and investment rates in some specifications or subsamples. This relationship is, perhaps, the strongest in Demir's (2009b) estimates for Argentina, Mexico and Turkey, which test whether an increase in the gap between real and financial profit rates decreases fixed investment. Demir finds a positive and statistically significant effect of this gap on investment, robust across specifications (p. 320). Orhangazi (2008a), similarly, finds a strongly statistically significant negative relationship between financial profits (normalized by the capital stock) and investment, although only among large firms. In fact, the relationship between financial incomes of the full sample of USA NFCs and investment is positive, albeit statistically insignificant. At the aggregate level, Stockhammer (2004) finds statistically significant evidence of a negative relationship between financial profits and capital investment in the USA and, in some specifications, also in the UK, but little evidence of a negative relationship in France or Germany. Notably, the statistical significance of this relationship disappears for the USA as well when also controlling for financial payments (Stockhammer, 2004, p. 735); these estimations that include both financial incomes and payments align with the statistically insignificant full-sample result in Orhangazi (2008a) and also the aggregate estimations in Orhangazi (2008b).6

Thus, while these papers point to a negative relationship between NFCs’ financial incomes and investment in some specifications, the results are sufficiently mixed to suggest that evidence of ‘crowding out’ is not clearly robust across contexts and specifications. As such, this literature raises questions about the necessary conditions for ‘crowding out’ to hold. Perhaps most importantly, the theoretical robustness of the predicted negative relationship hinges on the assumption that internal funds are limited. This assumption of limited internal funds excludes, however, two relevant cases: first, a case in which financial earnings augment a firm's available funds such that (some proportion of) these total funds may be allocated towards physical investment and, second, a case in which firms borrow to augment internal funds.

The first possibility is that financial earnings augment firms’ pools of internal funds, which can then be allocated in some proportion towards fixed or financial assets. Importantly, there is no a priori reason to expect these funds will be allocated entirely towards financial acquisitions, much less cause a further reduction in the acquisition of fixed assets. Demir (2009c), for example, finds that cash flows from financial investments have a positive effect on fixed investment in Turkey, although this positive effect is substantially smaller in magnitude than the (positive) effect of cash flow from operating profits. This result suggests that, in some circumstances, financial profits act as a dynamic ‘hedging mechanism’ that offer NFCs additional cash flow in subsequent periods, particularly in times of high uncertainty (p. 959). In other words, cash flows from financial investments may have a long-run positive effect on fixed capital investment. Notably, this analysis emphasizes financial cash flows; in contrast, Demir's (2009b) findings emphasize financial rates of return (i.e. financial profits per unit of financial assets), wherein a relative improvement in financial profitability relative to real profitability leads to a portfolio reallocation towards financial assets that depresses fixed investment.

In some contexts, however, financial profit rates may also complement ‘real’ earnings. Davis (2017), for example, presents evidence consistent with the negative predicted relationship between financial profit rates and investment above across all USA NFCs; however, firm size sub-samples point to a positive short-run relationship between financial profitability and investment for the largest quartile of firms.7 This result suggests possible complementarities between financial profits and the nonfinancial aspects of firms’ businesses that are only captured by the largest firms in the USA economy (Davis, 2017, p. 18). For instance, this result may corroborate examples of (large) NFCs’ expansion into the provision of financial services, including NFC provision of car loans and store-issued credit cards (Froud et al., 2006). These cases of captive finance not only generate financial profits, but also capture demand for a firm's nonfinancial output, thereby supporting fixed investment. This discussion, furthermore, suggests that – for firms able to capture these types of complementarities – a large differential between returns to lending and borrowing may not be necessary to generate NFC movement into financing activities.

Second, access to external finance (new borrowing) that augments a firm's pool of internal funds also implies that the acquisition of financial assets need not come at a trade-off with fixed investment.8 Because firms make investment and financing decisions subject to a finance constraint, decisions regarding uses of funds are interdependent with decisions regarding external finance. Notably, in the USA context, the post-1980 expansion of financial incomes and financial investments is concurrent with an expansion in gross debt on NFC balance sheets (see Section 3.2), suggesting that – at least at the sector-level – firms are not constrained in new borrowing. In this context, ‘crowding out’ – or what Kliman and Williams (2014) term ‘diversion’ of the share of profits invested in production towards financial uses – need not have taken place.

Kliman and Williams (2014), instead, contend that USA NFCs’ financial asset acquisitions were ‘almost wholly funded by means of newly borrowed funds throughout the entire post-World War II period’ (p. 77). While this conclusion is based on aggregate data showing the relative magnitudes of changes in financial asset holdings and liabilities, such that it is not possible to disambiguate what funds are used for what (only that, at the sector level, there are ‘enough’ funds to cover new financial assets out of new borrowing), this conclusion is also supported by the firm-level estimations in Davis (2017). Investment specifications that include NFCs’ outstanding stock of financial assets, in addition to the flows of income earned off these assets, point to a positive and strongly robust relationship between firm-level financial asset holdings and fixed investment (in the short-term, over time and across firm-size specifications). Thus, holding expected returns constant, ‘firms acquire financial assets – which ameliorate inherent risks of long-term and irreversible capital investments – concurrently with fixed capital’ (p. 20), similarly, suggesting that financial assets have not directly crowded out fixed capital investment among USA firms. Seo et al. (2016), similarly, find no evidence of a crowding out relationship between financial asset acquisitions and fixed investment in Korea.

Among firms facing constraints in access to external finance, however, the acquisition of financial assets may come at a trade-off with fixed capital investment. Thus, the fact that Demir (2009b) finds robust evidence of crowding out in emerging market economies is consistent with the expectation that credit rationing constrains a more significant set of firms in an emerging market context. Demir, furthermore, draws on these results to point to the persistence of capital market imperfections in Argentina, Mexico and Turkey, arguing that – despite predictions that financial liberalization should deepen capital markets and reduce agency costs, in turn, increasing capital market efficiency – there is no robust evidence of a reduction in credit rationing for these real-sector firms. In addition to highlighting the role of credit constraints, this discussion speaks to a broader point: namely, that the key mechanisms through which financialization is linked to changing investment behaviour are likely to vary across countries, in line with historical and institutional differences (see Lapavitsas and Powell, 2013; Seo et al., 2016; Karwowski and Stockhammer, 2017), as well as – within countries – both over time and by ‘types’ of firm (for example, those that are credit constrained versus those that are not).

3.2 Debt and Investment

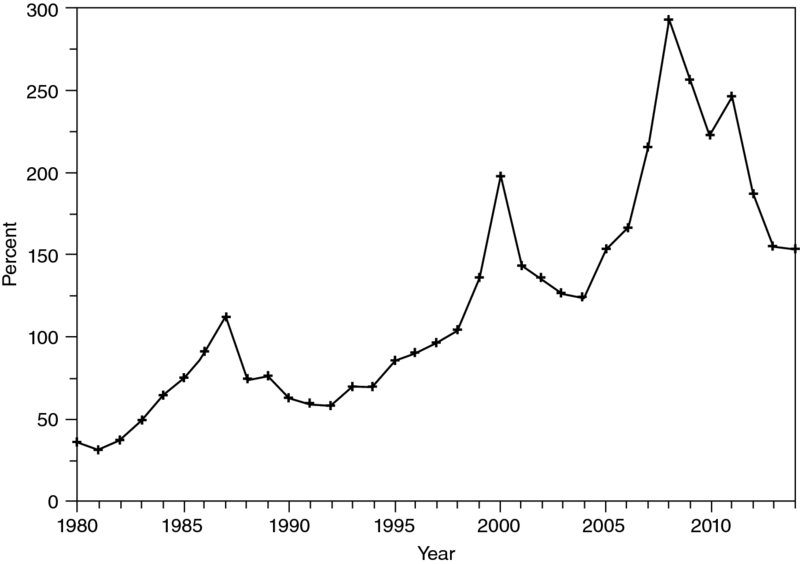

A dramatic rise in NFC (gross) leverage is, also, a key stylized feature of the post-1980 period in the USA economy that has been emphasized extensively in the financialization literature. This expansion of debt is evident both at the sector level (Palley, 2007), and also at the firm level among large corporations (Davis, 2016). Figure 2 plots the firm-level yearly means of total outstanding debt relative to total capital between 1950 and 2014 for the full USA nonfinancial corporate sector, capturing a dramatic expansion in debt over the post-1980 period. As indicated by the discussion in Section 3.1.2, new borrowing is closely linked to accounts of financialization and investment, particularly in the post-1980 USA economy. As a source of funds, new borrowing can be channelled towards three types of uses of funds: investment in fixed capital, investment in financial assets (or, analogously, saving) or ‘swapping’ debt for equity.

Figure 2. Gross Debt as a Percentage of Fixed Capital (The Across-Firm Yearly Mean of Nonfinancial Corporations).

Source: Compustat, author's calculations (series reproduced from Davis, 2016).

Notes: The series plots the across-firm yearly mean of total outstanding debt relative to the firm-level capital stock between 1950 and 2014. The ratio is winsorized to account for outliers. Debt is defined as the sum of current and long-term debt (Compustat items 34 and 142) Sales are drawn from Compustat item 12. The vertical line denotes 1980 to highlight the beginning of the period emphasized in the discussion.

Importantly, the financialization literature suggests a ‘de-linking’ between borrowing and physical investment in the post-1980 USA economy. Kliman and Williams (2014) contend, for instance, that borrowed funds are an ‘increasingly large source of the funds that drive the financialization process’ (p. 76), where ‘financialization’ refers to dividend payments and financial asset acquisitions. Using firm-level data, Mason (2015) points to a declining correlation between new borrowing and physical investment after the early 1980s. Similarly, the USA nonfinancial corporate sector's dependence on external borrowing for investment falls after the early 1980s, such that a declining share of sector-level capital investment is financed with external funds (de Souza and Epstein, 2014). De Souza and Epstein (2014), also, document similar trends for five European countries with major financial centres (the UK, Germany, the Netherlands, Switzerland and France). Notably, in Germany, the UK and Switzerland, this trend is sufficiently dramatic that the nonfinancial corporate sectors become net lenders of funds to the rest of the economy, reversing traditional patterns of inter-sectoral lending.

Given this ‘de-linking’, the literature on financialization suggests at least two possible reasons why firms (increasingly) borrow, without channelling these borrowed funds into traditional investment. First, a large – and growing – subset of the financialization literature suggests that growth in debt and shareholder payouts in the USA economy are linked (Dumenil and Levy, 2011; Kliman and Williams, 2014; Mason, 2015; Fiebiger, 2016). Of particular importance is the possibility that ‘financing for stock repurchases has been mainly from borrowing rather than from profits’ (Fiebiger, 2016, p. 355), such that debt increasingly replaces equity on NFC balance sheets. However, complete consideration of this channel also requires a discussion of shareholder value orientation, and is postponed to Section 4.

It is, second, plausible that (at least some part of) the expansion in borrowing is used to fund financial asset acquisitions. As discussed above in the context of crowding out, if financial asset acquisitions draw from borrowed funds, they need not come at a trade-off with fixed investment. Importantly, this point raises the question of why firms may borrow simply in order to hold more financial assets. Perhaps most notably, borrowing to fund financial asset acquisitions is consistent with the possibility that large NFCs are increasingly engaged in the provision of financial services. The clearest evidence of this possibility comes from case studies of large firms – like General Electric, General Motors and Ford – that have expanded their scope into banking activities (Froud et al., 2006). In the case that nonfinancial firms increasingly act like financial firms, their balance sheets structures should also more closely resemble those of financial firms (and, accordingly, be characterized by larger gross holdings of both debt and financial assets). More generally, however, this example indicates the importance of tying changes in NFC financial structure to behavioural changes, so as to disentangle, for example, the possibility that financial investments ‘crowd out’ capital investments, from the possibility that firms borrow to fund financial investments.

3.3 Behavioural Explanations of the Financialization of NFCs

As emphasized by this discussion, changes in firm financial portfolio and financing structure – as well as the financial flows that derive from these balance sheet stocks – are common across the existing empirical literature on financialization and investment. However, this discussion also highlights that the reasons why firm portfolio and financing behaviour have changed are important for disentangling the effects on investment. These financial flows stem from firm decisions to acquire financial assets, or to borrow, repurchase stock or pay dividends, and – accordingly – raise the question of why NFCs have changed their portfolio and financing behaviour over the post-1980 period such that these indicators rose in a dramatic and sustained way. Because firms make investment decisions subject to a finance constraint, the decision to invest is inherently interdependent with the decision of how to finance that investment, as well as with the decision not to allocate that finance towards another use – for example, to acquire financial assets or to finance (discretionary) shareholder payouts. As such, financial profits and NFC payments to the financial sector are both endogenous to the investment decision, and – as an explanation of the financialization of NFCs – cannot isolate what has changed in the post-1980 economy such that firms have changed their financial behaviour in a sustained way. Put differently, the interpretation of estimated coefficients drawn from reduced form relationships between flows of financial income and firm-level investment behaviour hinges on the theoretical basis of the investment function. Lack of clarity in the theoretical basis of the investment function, in turn, generates ambiguity regarding the behavioural and theoretical basis of estimated relationships.

As such, the implications of the same measure of financialization – for example, financial asset acquisitions – for investment differ if a firm acquires financial assets because they offer higher and faster rates of return than fixed assets, as compared to if a firm holds financial assets as part of a financial services division (wherein traditionally nonfinancial firms engage in borrowing and lending for profit). Similarly, an increase in NFC payments to finance due to higher interest payments (deriving from increased leverage) draws, on the one hand, on a firm's pool of available funds. On the other hand, however, higher leverage – and the corresponding increase in interest payments – is the result of a firm's decision to borrow in pursuit of some objective: for example, profits, targeting a stock price increase by financing repurchases, or covering rising interest obligations (Davis, 2017). Importantly, the implications for fixed investment likely vary with this objective. Borrowing to invest in an attractive capital investment project, for example, differs from borrowing to repurchase stock.

Similarly, while improved demand conditions may traditionally be expected to drive a portfolio reallocation towards physical capital, thereby reducing NFC holdings of financial assets, this expectation in fact hinges on the nature of a firm's activities. If, for example, a significant proportion of an otherwise ‘non’-financial firm's activities are financial (derived from the provision of financial services), and if the firm generates substantial complementarities between the financial and nonfinancial aspects of its business, the relationship between financial asset holdings and investment may instead be positive, as improved demand conditions could induce a firm's management to also expand the firm's financial services division. These examples speak to a broader point: continued research on financialization and investment requires development of a more complete behavioural narrative of why NFCs have ‘financialized’ – including changes in firm activities and managerial objectives that accompany this financialization process – to more fully elaborate the consequences for investment.

4. Shareholder Value Orientation

The primary behavioural channel analysed extensively in the existing literature, which links firms’ financial outcomes to changes in firm behaviour, emphasizes a shift in corporate governance norms associated with the growing entrenchment of shareholder value ideology (Lazonick and O'Sullivan, 2000; Davis, 2009). Arising out of the application of agency theory to firms, shareholder value ideology contends that agency problems between shareholders (owners) and managers lead to inferior corporate performance. The agency problem is argued to derive from moral hazard: managers may apply ‘insufficient effort’, undertake ‘extravagant investments’, pursue ‘entrenchment strategies’ to make themselves indispensable, or exploit expensive perks like private jets or box tickets to ball games (Tirole, 2006, p. 17). To mitigate this moral hazard, agency theory suggests specific mechanisms to better-align managerial and shareholder interests including a hostile market for corporate control (Jensen, 1986, p. 324) and stock-based executive compensation (Jensen and Murphy, 1990). While these mechanisms are designed to improve firm performance, the literature on financialization has linked changes in firm behaviour associated with growing shareholder orientation – and, in particular, increased managerial attention to financial measures of firm performance defined on a short-term basis – to declining fixed investment rates.

4.1 The Entrenchment of Shareholder Orientation in the USA Economy

The development of institutions supporting the maximization of shareholder value is particularly dramatic in the USA economy. Because these changes depend significantly on country-specific institutions defining the degree of shareholder power, it is, therefore, useful to specifically introduce the USA case. In the USA, these changes are summarized by a shift from the Chandlerian managerial firm of the initial post-WWII period – in which professional managers ran corporations with little shareholder oversight (Chandler, 1977) – to a ‘financialized’ or ‘rentier-dominated’ firm following the shareholder revolution (Stockhammer, 2004; Crotty, 2005; Mason, 2015). This ‘financialized’ or ‘rentier-dominated’ firm is characterized by a shift in managerial priorities towards an emphasis on shareholder interests and, in particular, the interests of short-term shareholders (Stout, 2012).

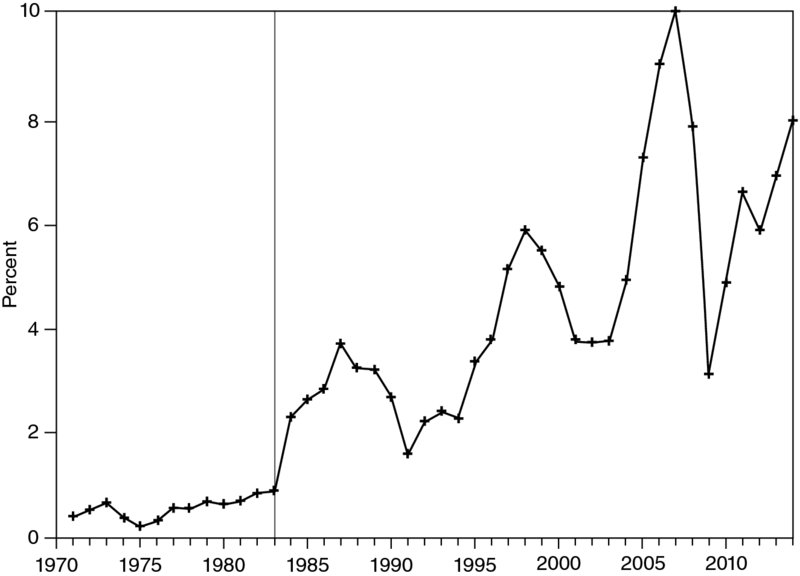

A wide-reaching set of institutional and regulatory changes over the post-1980 period – including growth in institutional investors, an expansion in stock-based executive pay, and regulatory changes encouraging stock buybacks – have supported this shift in corporate governance norms, encouraging attention to shareholder payouts and the ‘maximization of shareholder value’. First, the post-1980 period is characterized by significant changes in the structure of stock ownership, wherein institutional and activist investors increasingly dominate shareholding. Growth in the share of USA equities managed by institutional investors rises from 33% of total stock market capitalization in 1980 to 67% of by 2010 (Blume and Keim, 2012). Institutional ownership is, also, importantly, characterized by a shorter duration of stock ownership. Accordingly, stock market turnover has risen substantially over this period. Figure 3 highlights this increase in stock market turnover in the USA between 1980 and 2014; in this figure, the stock market turnover ratio is defined as the total annual value of shares traded relative to average market capitalization. Together with the expansion in institutional investors, increased turnover reflects a marked departure from the pre-1980 period – dominated by long-term household-level stockholding – towards increasingly ‘impatient’ stock market finance (Crotty, 2005).

Figure 3. Stock Market Turnover, USA Stock Market (1980–2014).

Source: World Bank, Stock Market Turnover Ratio (Value Traded/Capitalization) for United States, retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

Notes: This figure shows the total value of shares traded each year divided by the average market capitalization for this period.

The expansion of institutional investors, together with changes in Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) rules increasing the ease of communication between shareholders, has manifested in ‘shareholder activism, with large outsider investors publicly pushing management to increase payouts and adopt “value-enhancing” policies, pushing for seats on the board, sponsoring resolutions, and threatening to sell their shares en masse’ (Mason, 2015, p. 12). Crotty (2005) argues that this ‘impatient finance’ has contributed to growing emphasis on capital gains over long-term measures of firm performance and growth. Stout (2012), similarly, frames the expansion of institutional stock ownership in terms of the increasing power of short-term shareholders relative to long-term shareholders, generating ‘corporate myopia’ (p. 65). Short-term stockholding comes with a different set of incentives and, in particular, generates preferences for quick capital gains over long-term dividend growth. The rise of institutional and activist investors has, thus, arguably changed the constraints subject to which NFC managers operate, requiring greater managerial attention to stock-based indicators of performance.

Second, an expansion in stock-based executive pay directly affects managerial preferences by linking executives’ individual payoffs to the firm's stock performance (Lazonick and O'Sullivan, 2000). Frydman and Jenter (2010) document an upswing in stock option compensation in the early 1980s and emphasize, ‘The purpose of option compensation is to tie remuneration directly to share prices and thus give executives an incentive to increase shareholder value’ (p. 5; emphasis added; see also Lazonick, 2013). The expansion of stock-based executive pay has, notably, also been supported by tax code changes, including a 1993 amendment to the tax code (Code 152(m)) stipulating a $1 million cap on nonperformance-based pay, but no cap on ‘performance’-based pay. ‘Performance’ has, in turn, become increasingly synonymous with stock-price performance (Stout, 2012). Institutional investors have also been involved in the push for stock-based managerial pay (Lazonick 2009; Krippner, 2011). Hartzell and Starks (2003), for example, document that institutional ownership is tied to pay-for-performance sensitivity in executive compensation, where ‘performance’ again reflects stock price performance. A related change lies in a growing ‘market for managers’: whereas the initial post-WWII period was characterized largely by promotion within firms, an expanding ‘market for management’ has meant top management is increasingly likely to be brought in from outside the firm (Crotty, 2005; Kaplan and Minton, 2011; Mason, 2015).

These institutional changes are, third, supported by regulatory changes supporting own-stock repurchases. Of particular note is SEC Rule 10b-18, which first opened scope for (legal) large-scale repurchases by protecting managers from the threat of insider trading charges for targeting the firm's stock price (Grullon and Michaely, 2002; Lazonick, 2013; Davis, 2016). Further rule updates in 1991 and 2003 expand these safe harbour provisions, and shorten the waiting period between exercising and selling stock options (Lazonick, 2013; Davis, 2016). The dramatic post-1980 expansion in stock repurchases among USA corporations is closely correlated with these regulatory changes (Lazonick and O'Sullivan, 2000; Crotty, 2005; Davis, 2016). This secular expansion in repurchases is shown in Figure 4, which plots average industry-level repurchases across USA NFCs between 1970 and 2014; Figure 4 also indicates that this trend begins in 1983 (following SEC Rule 10b-18). Repurchase growth is accompanied by (more gradual) dividend growth; thus, total shareholder payouts exhibit secular growth after 1980, and dividends comprise a declining share of these total payouts over time (Grullon and Michaely, 2002). Importantly, own-stock repurchases clearly capture NFC emphasis on shareholder value. By repurchasing shares, managers increase stock-based performance measures (like return on equity, or earnings per share), for otherwise given profits. Thus, repurchases both appease institutional investors, and directly affect the part of executive pay comprised of stock-based instruments.

Figure 4. Gross Stock Repurchases Relative to Total Outstanding Equity (The Across-Firm Yearly Mean of Nonfinancial Corporations).

Source: Compustat, author's calculations.

Notes: The series plots the across-firm yearly mean of gross stock repurchases relative to the outstanding equity between 1971 and 2014. The ratio is winsorized to account for outliers. Gross repurchases are drawn from Compustat item 115. Total outstanding equity is drawn from Compustat item 144. The vertical line denotes 1983 to define the period after the implementation of SEC Rule 10b-18.

4.2 Shareholder Value and the Post-Keynesian Theory of the Firm

Growth in NFC own-stock repurchases, importantly, draws a clear link between shareholder orientation and changes in NFC financial behaviour associated with the financialization of nonfinancial firms (namely, increased shareholder payouts). In turn, shareholder value orientation has been linked to investment via changes in managerial objectives and/or the constraints subject to which managers make portfolio and financing decisions. The increasing entrenchment of shareholder value ideology has, first, been linked to firm investment behaviour via changing managerial objectives (Stockhammer, 2004; Davis, 2017). The rationale for analysing the impact of shareholder orientation on firm behaviour via changes in managerial objectives is perhaps most clearly reflected in the growing share of stock-based executive pay, which directly aligns managerial and shareholder interests. As such, managers are increasingly oriented towards short-term profitability – and, more specifically, stock-based performance indicators – such that managerial willingness to tie up funds in long-term irreversible fixed capital declines.

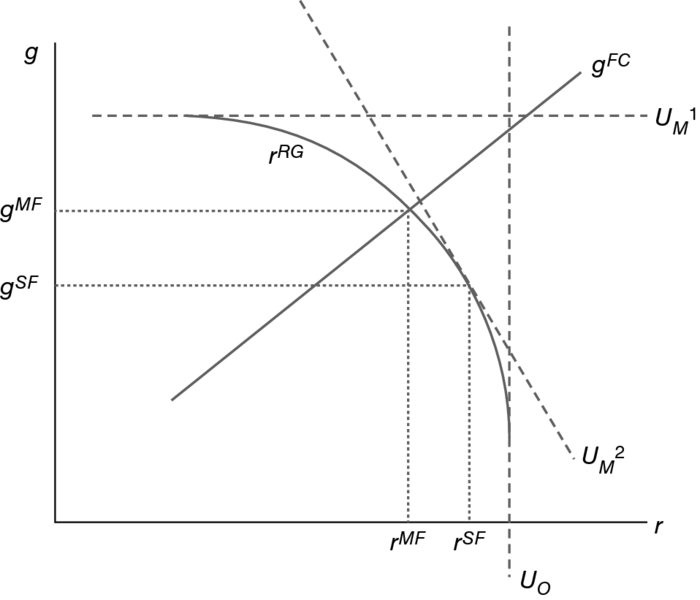

Building on the post-Keynesian theory of the firm in Lavoie (2014), Stockhammer (2004) develops a theoretical framework analysing the impact of changes in managerial preferences on investment, via a shift from ‘growth-maximizing’ to ‘profit-maximizing’ objectives. The investment decision, pictured in Figure 5, is determined by managerial objectives, the firms’ finance constraint (gFC), and the firms’ output expansion function (rRG) (Stockhammer, 2004; for additional elaborations of this framework see also Dallery, 2009; Hein and van Treeck, 2010; Lavoie, 2014). The finance constraint defines the maximum level of growth that can be financed by a given rate of profit. The output expansion frontier, in turn, defines the profit rate that can be achieved for a given investment rate (growth strategy). The firm is assumed to operate on the concave portion of the output-expansion function, such that additional investment harms profits – that is, there is a ‘growth-profit trade-off’.9

Figure 5. The Investment Decision in Stockhammer (2004).

Source: Adapted from Stockhammer (2004); r is the profit rate and g is the investment (growth) rate, gFC is the finance constraint; rRG is the growth-profit trade-off; Uo is the utility function of owners (defined as Uo = u(r)), and UM is the utility function of managers. With the shift from managerial capitalism to shareholder value orientation, managerial utility functions shift from UM1 = u(g) to UM2 = u(g,r). Investment declines from gMF (growth in the managerial firm) to gSF (growth in the shareholder-oriented firm), and profit rates rise from rMF to rSF. See Stockhammer (2004) and Lavoie (2014) for additional details regarding the theoretical framework.

The theoretical specification emphasizes the separation between ownership and control to introduce the possibility of divergence between managerial and shareholder preferences. Prior to the entrenchment of shareholder ideology, managers maximize firm growth (the investment rate), despite shareholders’ preferences for profit maximization. As such, managerial preferences are defined by U1M in Figure 5 (where U1M = u(g)), whereas owners’ preferences (UO) are a function of profits (r). As shareholder value orientation becomes increasingly entrenched, managerial preferences become increasingly ‘profit-maximizing’ (shown by the rotation to U2M = u(g, r)). As Figure 5 indicates, this increasingly ‘profit-maximizing’ managerial orientation, accordingly, drives a decline in the firm's investment rate (from the investment rate of the ‘managerial firm’, gMF, to the lower investment rate of the ‘shareholder-dominated firm’, gSF).10

Changes in firm financial behaviour associated with shareholder value – including, most notably, increased financial payout ratios – may, furthermore, change the position of the firm's finance constraint (Hein and van Treeck, 2008; Hein and van Treeck, 2010). In particular, the finance frontier rotates so as to further constrain the investment rate available to firms. Hein and van Treeck, (2010) contend that shareholder value orientation is, accordingly, associated not only with a change in managerial objectives, but also with a change in the firm's constraints as shareholders ‘compel firms to distribute a larger portion of profits’ (p. 210). Note, however, that an increase in distributed profits can also be understood as endogenous to the change in managerial preferences: namely, shareholder payouts increase and affect the position of the finance constraint because of the change in managerial objectives. As such, any changes in the position of the finance frontier are, in fact, also a consequence of changing managerial objectives. Furthermore, if shareholder payouts are financed, at least in part, through increased borrowing, this expansion in borrowing (reflecting additional finance available to the firm) can offset the shift in the firms’ finance constraint. Finally, Fiebiger (2016) contends that a concurrent shift in production from the domestic to the international sphere mitigates the extent to which the utility function describing managerial preferences rotates in the context of shareholder orientation; in particular, international fixed investment may, to some extent, have replaced domestic fixed investment.

4.3 Empirical Evidence on Shareholder Value and Investment

An empirical literature, also, provides econometric support for the hypothesis that growing shareholder orientation among NFC managers is associated with declining firm investment rates. This literature includes distinct approaches to operationalizing shareholder value orientation, which reiterate the bifurcation in empirical approaches to measuring financialization empirically shown in Table 1. In particular, some contributions rely primarily on NFCs’ financial payouts (Orhangazi, 2008a,b); others emphasize, more specifically, shareholder payouts (van Treeck, 2008; Mason, 2015); and still others equate shareholder orientation with increasing financial incomes (Stockhammer, 2004).

Stockhammer (2004) provides an early empirical analysis of shareholder orientation that extends the theoretical approach to the firm described in Section 4.2 to an empirical estimation of the investment function using aggregate data. The key empirical indicator of financialization is the rentiers’ income of nonfinancial business (interest and dividend income earned by nonfinancial business, at the sector level). This indicator is designed to capture the extent of managerial orientation towards financial profits. For the USA, Stockhammer finds a negative relationship between rentiers’ income and capital accumulation in most specifications, and concludes that these results provide preliminary evidence that financialization depresses capital accumulation (although it is important to note that the mechanism is shareholder value orientation and, thus, is one specific manifestation of financialization). Orhangazi (2008a), also, points to the possibility that the relationship between financial incomes and investment may be indicative – in part – of shareholder orientation, as higher financial profits can reflect ‘impatient finance’ (Crotty, 2005) and increased short termism (Orhangazi, 2008a, p. 868).

It is, however, important to note that there is not a direct mapping between the firm-level framework in Section 4.2 and the empirical analysis of this framework in Stockhammer (2004). First, by applying the firm-level framework to aggregate data, the empirical model excludes possible interactions between micro-level and macro-level outcomes. Skott and Ryoo (2008) note that, if each individual firm moves along its output-expansion frontier to a lower investment rate, aggregate demand falls. Thus, ‘an individual firm may face a perceived trade-off but this perceived trade-off does not extend to the macroeconomic level: changes in accumulation and financial behaviour affect aggregate demand and thereby the position of the frontier’ (Skott and Ryoo, 2008, p. 834). While this aggregation issue may not be vital for specifying the behaviour of an individual firm, it is important in the empirical extension of the firm-level model to the aggregate setting. Second, the theoretical framework emphasizes a distinction between profit-maximizing and growth-maximizing objectives; however, the empirical framework emphasizes a different distinction, between total profits and financially derived profits.

Furthermore, given the importance of increased payouts to shareholders in accounts of shareholder value orientation, the relationship between financial payouts and investment offers a more direct test of the effect of shareholder ideology on investment. Orhangazi (2008a) finds, first, a negative and statistically significant relationship between total NFC payments to financial markets (interest payments, dividend payments and repurchases), concentrated among large firms. As an explicit test of the relationship between shareholder orientation and investment, however, this approach is limited, given that total financial payments include payments to both creditors and to shareholders. In particular, shareholder orientation is plausibly identified with an increasing prioritization of shareholder over creditor interests, such that it is important to distinguish payouts to shareholders versus creditors. Notably, Davis (2017) finds an insignificant relationship (and a very small point estimate) between a firm's cost of borrowing and investment; the difference between the results in Davis (2017) and Orhangazi (2008a) suggest that the strength of Orhangazi's result captures payouts to shareholders rather than to creditors. Similarly, at the aggregate level, van Treeck (2008) includes interest and dividend payments separately in the empirical specification, finding a statistically significant negative effect of each variable on investment, but that the magnitude of the coefficient on dividend payments exceeds that on interest payments. Finally, given that buybacks are an increasingly important method of returning cash to shareholders, Mason (2015) points to the importance of combining repurchases with dividends to measure total shareholder payouts.

Departing from both financial-flow based indicators, Davis (2017) proxies shareholder value orientation by average industry-level repurchases, to capture the effect of increasingly entrenched norms encouraging managerial attention to stock-based performance indicators on investment. Both rentiers’ income and shareholder payouts are endogenous to the investment decision (and, as noted above, to the position of an individual firm's finance constraint), whereas average industry repurchases are plausibly exogenous to an individual firm. These results point to a negative relationship between average industry-level repurchases and fixed investment across all USA NFCs; furthermore, the magnitude of the estimate increases when focusing on the largest quartile of firms. Thus, holding all else equal in terms of expected profits, debt, and other financial variables, a ‘value’ maximizing firm invests less in fixed capital than a firm with traditional growth or profit-maximizing objectives. Furthermore, as is discussed above, a range of changes in financial behaviour are expected to accompany the increasing entrenchment of shareholder orientation including, notably, changes in debt and corporate borrowing. Mason (2015), for instance points to a declining correlation between borrowing and new physical investment, suggesting that – with a shift towards shareholder value maximizing objectives – firms increasingly take on external debt to repurchase outstanding stock, rather than to invest in new physical capital.

It is important to note that these mechanisms are highly institutionally contingent and depend substantially on institutions defining the degree of shareholder power in a particular economy. The analysis of shareholder orientation, therefore, offers a clear caution against applying institutionally specific features of financialization in cross-country contexts. If, for instance, one argues that rentiers’ income is indicative of growing managerial orientation to shareholder orientation, and this change in managerial preferences crowds out fixed investment, it is unlikely that this relationship between financial incomes and investment will also apply in economies where the degree of shareholder power is lower. Stockhammer's (2004) analysis speaks to this point: evidence of the effect of shareholder orientation on investment holds only in the USA and in some specifications in the UK, whereas France and Germany – both countries where the degree of shareholder power is lower – exhibit no such relationship. Analysing the salience of a link between shareholder orientation and investment in Korea, Seo et al. (2016), similarly, fail to find evidence of such a relationship.

5. Conclusions

This paper has surveyed the strand of the financialization literature that emphasizes fixed investment and capital accumulation. In this literature, there is growing consensus that certain features of financialization – in the USA context, most notably shareholder orientation and corporate short-termism – depress physical investment. Given the key role of fixed investment in economic growth, this literature raises important questions about the long-term macroeconomic effects of increased attention to short-term financial market-based indicators of firm performance in the USA economy. Notably, the possibility of economically meaningful negative links between financialization and capital accumulation is also echoed in a more recent mainstream literature that finds that, beyond a certain threshold, financial sector growth negatively effects GDP growth (Cecchetti and Kharoubi, 2012; Law and Singh, 2014; Arcand et al., 2015). Together, these results increasingly call into question a long-held tenet in mainstream macroeconomics: that more finance leads to more growth (Levine, 1997). Thus, as a largely heterodox literature on financialization has raised the question of ‘how big is too big?’ with respect to the size of the financial system (Epstein and Crotty, 2013), in the mainstream literature as well there is ‘an emerging notion: that there can be “too much finance”’ (Jordà et al., 2016, p. 32).