12

SOUTH–SOUTH AND NORTH–SOUTH ECONOMIC EXCHANGES: DOES IT MATTER WHO IS EXCHANGING WHAT AND WITH WHOM?

Omar S. Dahi

Hampshire College

Firat Demir

University of Oklahoma

1. Introduction

The term “South–South economic relations” captures a host of economic exchanges within the global South including trade in goods and services, capital flows, technology transfer, labor migration, and remittances as well as preferential trade agreements (PTA) and investment agreements and voting blocs within multinational institutions. For the most part, “South–South trade” is used as shorthand to capture all those modes of interactions and South–South trade and South–South economic relations tend to be used interchangeably. In much of the postwar period through the 1980s, South–South economic relations were a flashpoint for debate between supporters and critics of universal free trade, state-led development, and import substitution industrialization (ISI). The relatively scarce literature tended to focus overwhelmingly on the benefits or drawbacks of trade integration among developing countries.

The supporters’ rationale was the ostensible benefits for industrialization in the South. Prebisch (1959) had famously advocated the “enlargement of national markets through the gradual establishment of a common market” in Latin America to take advantage of specialization and economies of scale (p. 268). Myrdal (1956 p. 261) supported South–South integration to help the global South overcome the colonial legacy that biases them in favor of North–South trade.1 Linder (1967) had argued that similarities in consumer preferences, resource base, technological development, as well as institutions are likely to make South–South integration and trade more beneficial to Southern industrialization than North–South trade.

The critics on the other hand saw in South-South integration all that was wrong about ISI. According to Havrylyshyn and Wolf (1987, p. 158) if a Southern country “does a great deal of trade with other developing countries, the implication is that it has distorted its domestic prices.” South–South trade according to Deardorff (1987) and Havrylyshyn and Wolf (1987) was an attempt to recoup the losses from ISI. Given its inability to penetrate Northern markets due to the high cost and low quality of its consumer and capital goods, a large industrializer like Brazil would offload them to neighboring Paraguay due to preferential treatment. Amsden (1980, 1983, 1984, 1987, 1989), using her analysis of East Asian industrialization, countered these critics by arguing that much of South–South trade in capital goods was intra-industry and in intermediate products, most of which was not subject to preferential treatment. Moreover, she argued, South–South trade facilitated technology transfer and a “learning by exporting” in countries trying to climb the industrial ladder.

Research on South–South trade as an alternative remained relatively marginal throughout this period even when the structuralist literature on uneven development extensively critiqued North–South trade due to asymmetrical economic structures and patterns of specialization (Findlay, 1980; Darity, 1990; Dutt, 1992). As noted by Darity and Davis (2005, p. 154):

The role of government policy is not at the forefront of most of these [uneven development] papers. If we believe these processes operate and perpetuate international inequality, precisely how do we reverse them? Via industrial policy, South-South trade, South-South finance, autarky? Rarely does the formal literature on North-South trade and growth answer the question of how the world should be changed.

There is good reason for this lack. Research on South–South relations remained minimal because South–South trade and capital flows themselves remained relatively negligible throughout most of the postwar period. It was not until the 1990s that South–South economic relations took off and eventually brought the academic literature along with them. However, the post-1990s boom was fundamentally different from earlier ones. While most earlier studies focused on South–South relations under the ISI and the “old regionalism,” the rise in the past three decades has been under the neoliberal era and the “new regionalism” in which most countries of the globe have experienced significant trade and financial liberalization relative to the earlier period together with a simultaneous retrenchment of industrial policy.

Several themes emerge from this newly bourgeoning literature. First, South–South trade and finance is now a significant economic and political force for South countries as well as for the global economy. There is a near consensus therefore that South–South economic relations do matter and that they have the potential to have a significant developmental impact. Moreover, this impact may be positive or negative, that is, that it may help or hinder the long-term developmental goals of exchanging parties. Second, much of South–South manufactures trade is concentrated in high-technology-and-skill content, opening the door for potential long-run dynamic gains from trade. However, these gains are being increasingly concentrated within a small number of South countries. The global South is, in fact, splitting into two groups, which we refer to as the Emerging South and the Rest of South with very different outcomes. While there is evidence for gains through South–South trade, there is also evidence that the Emerging South is rising at the expense of the Rest of South. Finally, the South–South exchanges have expanded significantly to cover issues including financial flows and technology transfer, among other topics. The overall conclusion of this diverse literature is that while it does matter who is exchanging what and with whom, South–South trade is not a panacea for the development challenges in Southern countries. On the contrary, South–South exchange themselves may become a potential threat for development for some of the Southern countries.

The rest of the paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 provides a framework for situating the literature by reviewing the traditional targets of development as well as the benefits and drawbacks of integration into the global economy in both South–South and North–South directions. By establishing the general goals for development in the global South and the means to achieving those goals, we can better appreciate the debates in the academic literature on the relative merits of South–South and North–South trade. Section 3 provides a discussion on the definition of North and South and offers a statistical overview of South–South economic relations that also helps contextualize the debates within the literature. Section 4 introduces the theoretical and empirical literature on the relative costs and benefits as well as relative constraints and bottlenecks in South–South and North–South economic exchanges. Section 5 provides a discussion of the China in Africa debate that helps explain the complexities in South–South exchanges. Section 6 debates whether South–South is still a useful analytical category with the potential of uplifting developing countries as a whole. Section 7 concludes.

2. Economic Development and Global Integration within the Global South

In order to understand the evolution of the literature on South–South trade, it is necessary to anchor the discussion on the main question that the literature is responding to. The debate about South–South trade and its comparative merit relative to North–South trade is in essence a debate about economic development strategies within the global South. Linking South–South relations to trade was explicitly made by developing countries themselves starting with the Bandung Declaration of 1955 to the New International Economic Order of 1974 within UNCTAD to South–South coalitions such as the Like Minded Group within the World Trade Organization (WTO) (Dahi and Demir, 2016). Through those various initiatives, the majority of developing countries have declared the goals of development to be solving the problem of poverty, raising the living standards of their citizens, and achieving a level of economic independence to accompany political independence. This leads to two central questions: What kind of processes lead to achieving those goals, and how does integration into the world economy help or hinder those processes?

The answers to those questions have been at the core of debates within economic development and international economics fields over the past half-century. Though the debate itself is outside the scope of this paper, much of the literature reviewed here assumes that the engines of economic development and structural change within the global South emanates from increasing industrialization, technology-and-skills upgrading, as well as the development of effective institutions.2 Economists have long argued that there exists a positive relationship between industrialization and income growth (Leontief, 1963; Kaldor, 1967; Chenery et al., 1986; Murphy et al., 1989) though this relationship has not gone without critiques (Easterly and Levine, 2001). Technological upgrading and entering into knowledge-based economies are also shown to be engines of growth (Romer, 1990; Landes, 1998; Rodrik, 2007). Overall, there appears to be a consensus in this literature suggesting that what you produce and export matters for long-run development and growth.

Accepting the goals of development and the general means to achieving those goals leads to the key questions facing developing countries. What kind of barriers or binding constraints, internal or external, does the average developing country face in achieving those goals, and what may be the benefits or drawbacks from integration into the global economy? Internally, most developing countries found themselves in vicious cycles of low savings and capital investments, dependence on primary product exports, underdeveloped institutions, low levels of financial depth and high levels of capital market imperfections, as well as a variety of information and coordination failures. These internal constraints also shape the developmental potential of South–South versus North–South exchanges through adaptive capabilities, suitability of new technologies, transferability of skills and technology, and differences in demand structures. This is not to mention that many countries with extended experience with colonialism often had domestic vested interests in agricultural or natural resource extraction rather than in industrial development. Externally, the significant gaps that existed at the industrial and technological level were coupled by power and knowledge asymmetries, particularly as the United States and the United Kingdom wrote the rules of the game in the post-WWII era through the Bretton Woods institutions.

What then are the purported benefits of integration into the world economy? The mainstream orthodoxy since the 1970s has argued that integration into the world economy is the best path for development and growth and that inward orientation hurts development (Little et al., 1970; Krueger, 1977, 1997; Bhagwati, 1978; Michaely et al., 1991; Dollar, 1992; Harrison, 1996; Dollar and Kraay, 2004). Integration has many potential benefits. Openness, particularly in trade, allows countries to access advanced technology that facilitates the process of growth and structural transformation and helps overcome domestic market constraints, enabling the industrial sector to achieve economies of scale, among other benefits (Grossman and Helpman, 1991). Likewise, financial liberalization is expected to drive down the cost of capital (Henry, 2000), increase investment and growth (Bekaert et al., 2001, 2005), and lower financial constraints on growth (Rajan and Zingales, 1998).

In short, developing countries want to industrialize and upgrade their technological capacity, and integration into the world economy may provide them with the means to do so. Nevertheless, the question then becomes whether North–South or South–South economic relations particularly help or hinder achieving developing country goals. The rest of the paper traces the evolution of this debate.

3. Evolving Nature of South–South and North–South Exchanges

3.1 Where Is the South?

Defining the South and the North is not an easy task and the exact categorization of countries into one of these two groups partly depends on the research question at hand as well as the underlying assumptions for particular theoretical approaches. The countries of the South are usually defined as those developing (or underdeveloped/less developed/Third World/peripheral) countries in Latin America and the Caribbean, Africa, and most of Asia excluding Japan and Oceania, as well as transition economies. This makes the North defined as developed (First World/center/core/metropolis) countries including those in North America (except Mexico), Western Europe, Japan, Oceania, and Israel.

The critique that both the North and the South are composed of a wide range of countries with high levels of heterogeneity in their economic, social, and political structures as well as in their factor endowments, development policies, historical experiences, etc., is a valid one. Furthermore, these countries have a diverse set of interests and treating them as homogenous units may create a fallacy of composition.3 The literature we review is mostly aware of these objections and the North and South classification does not assume that countries are homogenous within each group. Rather, it is based on the stylized facts showing that similarities are more than differences within each group and that there are some fundamental differences between countries across these groups. Another issue is that the list of Northern club membership is a dynamic one even though there is strong hysteresis. Last, how much of this country heterogeneity needs to be emphasized depends on the research question. For example, differences in economic development trajectories of Southern countries for the last 30 years necessitate an additional distinction to separate Emerging South economies (i.e., Newly Industrialized Countries [NICs]/semiperiphery) from the Rest of South.

Notwithstanding these objections, we argue that the North versus South distinction is a useful one with some caveats, particularly regarding emerging market economies with fast-track industrialization and technology-and-skills upgrading. Using Occam's razor, we chose the definition with the least number of assumptions and have classified countries in three groups: the North (23 countries), the Emerging South (55 countries), and the Rest of South (157 countries).4 “The North” refers to the industrialized high-income countries. “Emerging South” refers to the more advanced and, at a minimum, partially industrialized countries of the South, most of them from what the World Bank refers to as the middle-income group, and a few from the NICs group. The term “developing,” in the true sense of the word, refers to these countries. “Rest of South” includes those Southern countries that are not included in the Emerging South category. Global South (or when we simply state, South–South), on the other hand, refers to all countries of Emerging South and Rest of South combined. We should note that while most countries of the global South are in this group, the majority of Southern population lives in Emerging South countries.

In our classification, we have taken into account countries’ incomes, production and trade structures, factor endowments, and human and institutional development, and have kept the group of countries constant over time. Allowing country switching between groups would create inconsistency as we would have to exclude countries that move up the economic ladder, and to do so would introduce a selection bias. Furthermore, moving the new graduates from the global South class would prevent us from understanding how these now-rich countries have become rich. The rule of thumb in these decisions, especially in applied research, is the timing of a particular country's move up (or down) the development ladder. The obvious examples are Argentina's downgrading from North to South in early 20th century and the upgrading of South Korea in late 20th century.

3.2 Stylized Facts on South–South and South–North Exchanges

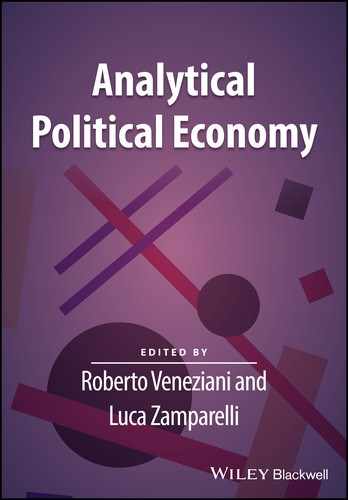

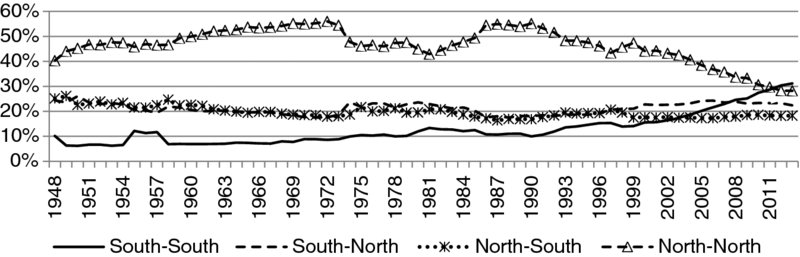

For most of post-WWII period, South–South trade remained marginal, fluctuating at around 10% of world trade in merchandise goods. Historically, an interesting feature of South–South trade is that it is concentrated in relatively sophisticated manufactures compared to South–North trade (Amsden 1989). Since early 1990s, South–South trade has grown substantially, reaching as high as 28% of world merchandises trade by 2013 (Figure 1).5 North–South and South–North trade, however, remained relatively stable, with a slight increase for the latter. The importance of South–South exports in total Southern exports has also increased substantially, reaching from around 20% in the 1950s to 60% in 2013. And yet, a majority of this, around 70%, is from trade between Emerging South countries. Likewise, more than 85% of South–North trade originates from Emerging South countries as seen in Figure 2.

Figure 1. The Share of South and North in World Merchandise Goods Trade, 1948–2013.

Source: IMF Direction of Trade Statistics (2014) and authors’ calculations.

Notes: South–South, South–North, North–South, and North–North refer to the share of each group of exporters in world merchandise exports.

Figure 2. Share of Emerging South within South–South and South–North Merchandise Exports, 1948–2013.

Source: IMF Direction of Trade Statistics (2014) and authors’ calculations.

Notes: Emerging–Emerging/South–South and Emerging North/South–North refers to the share of Emerging–Emerging country trade and Emerging North trade in total South–South and South–North trade, respectively. South–South/South refers to the share of South–South trade in global South exports to the rest of the world.

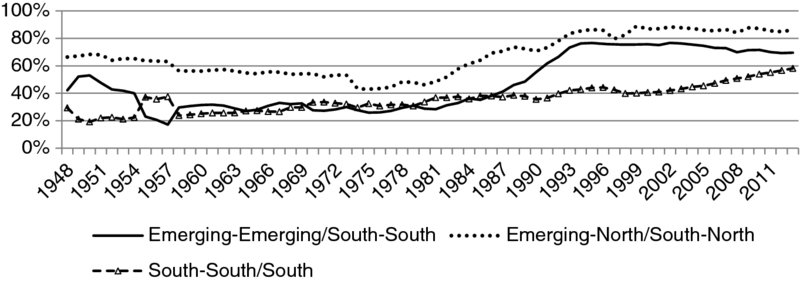

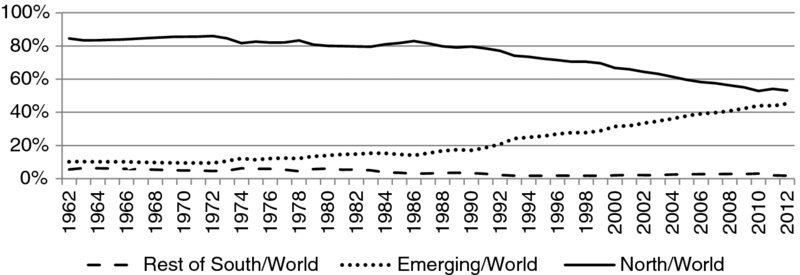

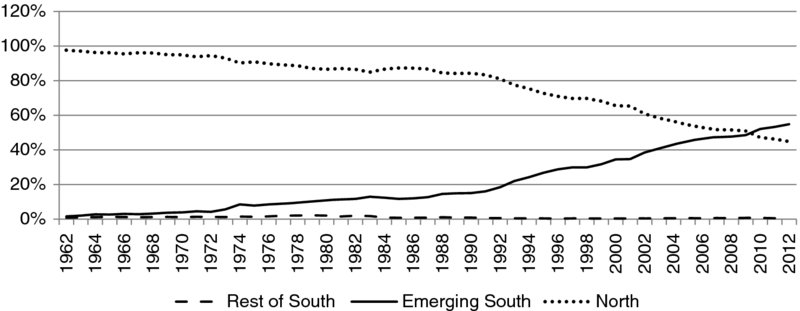

During this period, the production structures of some Southern countries have gone through a major metamorphosis, becoming more industrial rather than agricultural or natural resource-dependent. In fact, as shown in Figure 3, the share of Emerging South countries in world manufactures exports steadily increased from 10% in 1962 to 45% in 2012, while the share of the Rest of South countries remained negligible, fluctuating at around 2%–3% of world trade since the 1980s. The situation with high-technology-and-skill-intensive manufactures is even worse such that the share of Rest of South stayed at or below 1% and has never been more than 2% of world trade. Meanwhile, the share of Emerging South in world exports of high-skill goods increased from 2% in 1962 to 55% in 2012, surpassing the share of the North (45%) (Figure 4).

Figure 3. Share of South, Emerging South, and North in World Manufactures Exports, 1962–2012.

Source: MIT Media Lab (2015) and authors’ calculations.

Notes: Rest of South/World, Emerging/World, and North/World refer to the share of Rest of South, Emerging South, and the North in world manufactures exports.

Figure 4. Share of South and North in World High-Skill Manufactures Exports, 1962–2012.

Source: IMF Direction of Trade Statistics (2014) and authors’ calculations.

Notes: The definition of product classifications is provided in the appendix.

We see a similar trend in South–South financial flows even though they have remained negligible up until very recently, and this is reflected in the relatively minimal literature we have on the subject. In fact, before the 1990s, most of the South was in a state of financial autarky with regard to equity and private debt flows. Besides Southern countries emerging as a source of debt, equity of aid coincides with the rise of few Emerging markets after the 2000s (UNDP, 2013). In 2013, FDI inflows to the South amounted to 61% of global inflows (including both the North and the South), while FDI outflows from the South reached its highest level of 39% within global outflows. We discuss the financial aspect of South–South exchanges further in Section 4.4.

4. Theory and Empirics of South–South Trade and Finance

4.1 Static Theories of Trade

The traditional Ricardian and HOS (Heckscher–Ohlin–Samuelson) model approaches the issue of South–South trade with suspicion as it sees growing South–South trade coming at the expense of North–South trade. The static HOS model predicts that in countries with higher capital/labor ratios (i.e., the North), the relative cost of capital-intensive goods will be lower, while in countries with lower capital/labor ratios (i.e., the South), the relative costs will be lower for labor-intensive goods, reflecting the effect of factor endowments on each group of countries’ comparative advantage in international trade. Through specialization, the capital-abundant countries will export more capital-intensive products to labor-abundant countries and receive more labor-intensive products in return. If we considered factor endowments as skilled and unskilled labor, we would get the same outcome. Countries with higher skilled/unskilled labor ratios will export more skill-intensive products and import relatively lower-skill-intensive products. We should note that the static nature of the HOS assumes that international division of labor and specialization should be based on current factor endowments.

The HOS model was extended to account for the rise of the NICs (i.e., the Emerging South), so that they appear as middle countries (Deardorff 1987). Unlike the older theories, which assume two countries with two goods and two factors of production, this formulation assumes a three-country and two-good model where factor endowments lie on a continuum, with relative labor abundance on one end, and relative capital abundance on the other. A middle country is somewhere in between and imports labor-intensive goods from a less-developed Southern country (i.e., Rest of South) and capital-intensive goods from a Northern country. At the same time, the Emerging South country exports capital-intensive goods to the low-income Southern country and labor-intensive goods to the Northern country (Krueger, 1977; Baldwin, 1979; Khanna, 1987; Deardorff, 1987). Therefore, the Rest of South competes with the Emerging South in labor-intensive but not in capital-intensive products, while the North competes with the Emerging South in capital-intensive but not in labor-intensive products.

Static neoclassical trade theory treats the South–South trade in capital or skill-intensive goods as a result of misguided ISI policies, which distorted relative prices and caused allocative inefficiencies and welfare losses. Accordingly, those Southern countries that had failed to develop high-quality and competitive capital-and-skill-intensive products dump their lower quality and overpriced industrial products on other Southern countries. Thus, Southern consumers end up being penalized by being forced to buy low-quality refrigerators, televisions, machinery, or cars from their Southern partners, driven by trade diversion from the North (Diaz-Alejandro, 1973; Havrylyshyn and Wolf, 1987; Bhagwati et al., 1998; Panagariya, 2000). This critique of South–South trade is therefore also a critique of the ISI model in developing countries. The basic idea behind the ISI was antithetical to the static HOS model as it argued that industrial upgrading is not only possible but it is also desirable for less developed countries with low capital/labor and skill-intensity ratios.

4.2 Dynamic Theories of Trade

The development of neoclassical new trade theory starting with Krugman (1979) led to another wave of criticisms of South–South economic integration efforts. By then, it had become obvious that most world trade was between similarly endowed economies, that is, North–North rather than North–South, and it was intra-industry rather than interindustry, running against the predictions of the HOS theory. New trade theory introduced imperfect competition, including monopoly rights over new technology, increasing returns, differentiated products, and mobile capital, with special attention to intra-industry trade. Unlike the static neoclassical trade theory, the evolution of factor endowments, technology, skill intensities, and factor productivity has come to the center stage of trade analysis.

Compared to the neoclassical theory, heterodox trade and development theory had always focused on dynamic gains, or lack thereof, from international trade. Issues seemingly introduced by new trade theory, such as imperfect competition, increasing returns and endogenous technological change (together with surplus labor), were already a key feature of early classical development theory (Ros, 2001, 2008, 2013, ch. 2). While the heterodox macroeconomic literature on North–South and South–South trade is rich and diverse, the main debates on the subject mostly originated from the structuralist school.6 Therefore, we will mostly compare neoclassical trade theory with the structuralist and related literature in this section. In what follows, we will summarize the main points from the neoclassical and structuralist schools on South–South versus North–South trade, emphasizing the binding constraints and developmental effects of economic interactions that favor one over the other. We should also note that the division between the neoclassical and structuralist literature has increasingly become blurred as it is possible to find arguments for and against South–South trade from both schools.

4.2.1 Productivity Spillovers, Technology Frontier, and Adaptive Capabilities

One strain of neoclassical new trade theory argues that North–South trade integration is mutually more beneficial as it allows for exploitation of economies of scale, and faster adoption of newer and better technologies and skills, leading to skills-and-technology upgrading and productivity gains, which would not be possible under South–South trade. Otsubo (1998), for example, argue that only after the South has liberalized trade with the North and begun producing according to their comparative advantage (i.e., labor-intensive goods), will there be a chance for the expansion of intra-industry South–South trade. Schiff (2003), Schiff et al. (2002), and Schiff and Wang (2006, 2008) also suggest that the highest impact on Southern total factor productivity (TFP) comes from the North through trade-induced technology diffusion. That is, the potential for technology transfer is higher when the technology gap between the trading partners is larger. As the South is positioned further away from the international technology frontier, North–South trade offers a higher chance of technology diffusion than South–South trade. North–South trade integration is also suggested to accelerate vertical specialization or value-chain fragmentation, allowing for faster catching up with the North (Krugman, 1995). Thus, with regard to technological acquisition, Southern countries are to have a wider range of choices in the Northern technology market and therefore can adopt the best technologies with the least cost and effort. In this literature, as will be discussed further later, capacity and capability of technology adoption are seen as one and the same thing.

On the other hand, for other strands of this literature, the existence of a vast technological gap between the North and the South limits gains from North–South trade and prohibits expansion of intra-industry trade. As the gap is smaller in South–South direction, there is arguably a bigger potential for learning by exporting in more sophisticated manufactures. This view challenges the orthodox view about technology transfer. What is suggested here is the opposite of the earlier view: the closer two countries are in technological development, the more likely they are to benefit mutually from trade since the technology is more appropriate for local conditions, including consumer preferences (more on this in Section 4.2.2), production structures, resource bases, and institutions (World Bank, 2006; Caglayan et al., 2013; Dahi and Demir, 2013; Regolo, 2013; Bahar et al., 2014; Cheong et al., 2015; Demir, 2016; Demir and Hu, 2016).

On this issue, the new trade theory has converged to the older structuralist tradition, which made the exact same arguments in favor of South–South trade (Amsden, 1980, 1987; UNIDO, 2005). Particularly, because of its higher skill-and-technology intensity, South–South trade is argued to have dynamic long-run benefits (Amsden, 1980, 1983, 1984, 1987, 1989; Chang, 2002, 2000, 2001; Wade, 1990). Assuming that learning and other spillover effects are the highest in the production of higher skill manufactures, South–South trade therefore offers higher potential for long-term development as it stimulates greater industrial production and skill-and-technology upgrading. Besides, South–South trade offers more opportunities in intra-industry trade in industrial products than the North–South trade, which is interindustry, with the South exporting relatively lower skill-and-technology-intensive products.7 The importance of manufactured goods for industrial upgrading and growth was first raised by Kaldor (1967). While the classical development theory and the structuralist approaches have long argued that what you export matters for long-run development, which is seen as a dynamic process reinforced by sectors that enjoy increasing returns, neoclassical new trade theory, despite starting from different assumptions and often arriving at different policy conclusions, has increasingly recognized the importance of export structure and export diversification for skills upgrading and growth (Antweiler and Trefler, 2002; Imbs and Wacziarg, 2003; An and Iyigun, 2004; Hausmann et al., 2007).

Table 1 shows that while the share of medium-skill manufactures in intra Rest of South trade has been around 14%–24%, on average, in each decade since 1960s, it was around 2%–4% in Rest of South–North trade. The same is true for high-skill goods. For intra-Emerging South trade in medium and high-skill goods, we again find a similar pattern. During the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, for example, the share of medium-skill goods in intra-Emerging South trade was more than twice higher than in Emerging South–North trade. Table 2 supports these findings by showing the destination market distribution of medium and high-skill exports of Southern countries. During the Great Recession period of 2009–2012, for example, 35% of Rest of South high-skill exports were to other similar countries and 42% were exported to Emerging South countries. In fact, for most of the years between 1962 and 2012, more than half of Rest of South exports of medium- and high-skill goods were to global South countries, be that Rest of South or Emerging South.

Table 1. Share of High- and Medium-Skill Exports in Total Exports in Each Direction of Trade

| High-skill | South–South | South-Emerging | South–North | Emerging-South | Emerging–Emerging | Emerging-North |

| 1962–1969 | 2% | 2% | 0% | 1% | 2% | 1% |

| 1970–1979 | 2% | 1% | 1% | 2% | 4% | 4% |

| 1980–1989 | 3% | 1% | 1% | 4% | 9% | 8% |

| 1990–1999 | 3% | 2% | 1% | 7% | 18% | 17% |

| 2000–2008 | 5% | 2% | 1% | 8% | 28% | 22% |

| 2009–2012 | 7% | 1% | 1% | 10% | 27% | 21% |

| 1962–1969 | 14% | 13% | 3% | 6% | 8% | 2% |

| 1970–1979 | 15% | 6% | 2% | 13% | 14% | 5% |

| 1980–1989 | 18% | 10% | 4% | 20% | 20% | 10% |

| 1990–1999 | 15% | 10% | 4% | 29% | 23% | 16% |

| 2000–2008 | 21% | 8% | 4% | 29% | 21% | 20% |

| 2009–2012 | 24% | 9% | 4% | 30% | 23% | 22% |

Source: MIT Media Lab (2015) and authors’ calculations.

Notes: Skill-classification is based on Lall (2000). High-skill refers high-technology and skill-intensive manufactured goods. For product codes, see the Appendix. The values refer to the share of high and medium-skill goods in total exports within each direction of trade.

Table 2. Share of High- and Medium-Skill Goods in South–South Trade

| High-skill | South–South | South-Emerging | Emerging-South | Emerging–Emerging |

| 1962–1969 | 25% | 30% | 11% | 27% |

| 1970–1979 | 25% | 16% | 6% | 19% |

| 1980–1989 | 17% | 14% | 4% | 21% |

| 1990–1999 | 7% | 30% | 3% | 34% |

| 2000–2008 | 23% | 42% | 2% | 42% |

| 2009–2012 | 35% | 42% | 3% | 51% |

| Medium-skill | South-South | South-Emerging | Emerging-South | Emerging-Emerging |

| 1962–1969 | 24% | 28% | 17% | 38% |

| 1970–1979 | 35% | 22% | 17% | 31% |

| 1980–1989 | 23% | 26% | 12% | 32% |

| 1990–1999 | 9% | 44% | 9% | 38% |

| 2000–2008 | 22% | 44% | 9% | 35% |

| 2009–2012 | 24% | 53% | 9% | 43% |

Source: MIT Media Lab (2015) and authors’ calculations.

Notes: Medium-skill and High-skill refer to medium- and high-skill manufactured goods. The values refer to the share of high and medium-skill goods in each direction of trade as a percentage of total exports of these goods to all directions. The differences from 100 percent gives the shares of exports to the North.

Furthermore, being the technological laggard, the South is argued to be in a dependent relationship regarding the direction of technological change. Particularly, being at the technological frontier, the North controls the direction of technological innovation, which is conditioned by Northern endowments and preferences, making it more capital-intensive (Stewart, 1982; 1992, p. 81; Kaplinsky, 1990; Acemoglu, 2015). Thus, products produced by the North are biased against Southern preferences and are inappropriate in terms of production techniques and product characteristics, which the South accepts because of lack of alternatives. Conversely, South–South exports, which embody older technologies, might be more appropriate for skill and technology adoption, matching Southern production and demand structures as well as factor endowments and market size than Northern exports with cutting-edge technologies (Stewart, 1982; Chudnovsky, 1983; Amsden, 1984, 1987; Bhalla, 1985; Kaplinsky, 1990; Nelson and Pack, 1999). Environmental appropriateness, including climate conditions or land use patterns and soil fertility of a chosen technology, adds another dimension to this debate as large-scale versus small-scale production processes have different implications for resource-poor or environmentally risky Southern countries that lack the resources to guarantee environmental safety and protections (Schumacher, 1973; Atta-Ankomah, 2014). Akamatsu's (1962) “flying geese” made similar arguments about the rise of Japanese industrialization. The size of the market and scale economies also affects the choice of technology available to Southern and Northern producers (Stewart, 1982; Kaplinsky, 1990; He et al., 2012; Atta-Ankomah 2014). Therefore, technologies that are more suitable for Southern firms in smaller markets will not be necessarily available from Northern suppliers, whose capital goods are more suitable for large markets.

The assimilation argument of Stewart (1992) and Nelson and Pack (1999), among others, matches with what Lall (2000, 2001) refers to as the capabilities approach to technological change. Accordingly, developing country firms are constrained by imperfect knowledge of technological alternatives, and finding appropriate technologies is a difficult and costly process. Imported new technologies require creating new skills and know-how to master their tacit knowledge, which varies by the kind of technology in question. Learning costs and adaptive capabilities therefore create barriers for technology adoption and limit the ability of Southern firms to choose the best technology available from the North. Thus, national abilities, not comparative advantage in factor endowments, determine a country's ability to master and use effectively a given technology. The greater the gap in tacit technological knowledge required in the production processes, the smaller the possibility for technological acquisition and knowledge growth. Therefore, the adoption costs are an increasing function of the knowledge and technology gap between the importers and suppliers (Amsden, 1987, p. 133). It must be stressed that the relevant literature argues for targeted industrial policy in promoting technological development, whether through North–South or South–South exchanges as has been shown for the case of Costa Rica, Brazil, India, South Korea, and elsewhere (Salazar-Xirinachs et al., 2014).

More recent advances in neoclassical research also support these observations. Acemoglu (2001), 2002, p. 783, 2007, 2015) and Acemoglu and Zilibotti (2001), for example, argue that market size, the relative scarcity of factor endowments, including their elasticity of substitution, and skills scarcity bias the direction of technological change. The technologies developed in the North therefore will be inappropriate to the needs of the South as they will not correspond to lower capital and skill intensities in developing countries. Caselli and Coleman (2001) also show that the level of human capital development and industrial development level of importing countries influence technology adoption. In the industrial organization field, there is indeed a long literature exploring how the choice of technology is endogenous to firm, market, and consumer characteristics.8

Given the similarities in technological development, South–South trade therefore allows for easier technological innovation (Amsden, 1984, 1987; Lall et al., 1989; Lall, 2000, 2001). These production systems are also more likely to be labor-intensive, and thus, allow for a more efficient use of surplus labor in the South while lowering license costs (Pack and Saggi, 1997). Recent empirical work using case studies shows that developing country technologies might indeed fit better for local needs, demand structures, market size, factor endowments, and adaptive capabilities (He et al., 2012; Atta-Ankomah, 2014; Agyei-Holmes, 2016; Xu et al., 2016).

4.2.2 Preference, Demand, and Income Similarity

Another seeming convergence between the neoclassical and structuralist literature is the recent work on Linder's preference similarity theory on consumer demand, which provides support for South–South over North–South trade (Hallak, 2006, 2010; Fajgelbaum et al., 2015). Linder (1967) suggested that inventors, innovators, and entrepreneurs are stimulated by home demand as they develop products to fit home market tastes and preferences. Later, they export products to those countries with tastes and preferences similar to those at home. Thus, the reason why most Northern trade is with other Northern countries and why it is intra-industry is because of the demand structure: the incomes, tastes, and preferences of developed countries are similar, and therefore they buy differentiated but similar products from each other (Krugman, 1980). South–South trade may therefore fit the demand structure of Southern consumers better than North–South trade. Furthermore, because entry barriers are higher in South–South direction, be that because of higher trade barriers, transaction, and transportation costs, colonial-era distortions that favor Northern countries, language differences, or lack of trade financing and credit, Southern consumers buy inappropriate Northern goods that do not match their demand structures, reducing overall welfare.9 The South also loses in North–South trade as it cannot export products that it is most efficient at producing (Linder, 1967, p. 37).

Accordingly, there are differences in consumer demand structures in the North and the South as certain products have “high,” while others have “low”-income characteristics and preference structures (Copeland and Kotwal, 1996; Murphy and Schleifer, 1997; Hallak, 2006, 2010; Fajgelbaum et al., 2015). Lancaster's (1971) approach to consumer demand also argues that consumers desire certain characteristics of goods rather than the goods themselves. The perceived quality differences between Southern and Northern goods of the same type also create some friction between Northern and Southern consumer preferences. For example, while there is little evidence showing that Chinese leather bags or watches are of lower quality than Italian bags or Swiss watches, the price differences are significant, reflecting differences in consumer demand for Southern and Northern goods (Brucks et al., 2000; Fontagne et al., 2008). Loren and Eric (2016), for example, showed that despite a lack of quality differences, Chinese excavators are sold at a significant price discount to foreign competitors. Therefore, specialized products in South–South trade may be subject to smaller perceived quality biases than in North–South trade, allowing Southern producers a better chance of exporting.

Recent empirical work supports Linder's theses showing that the level of institutional and cultural similarity as well as closeness in incomes, endowments, technological, and preference structures between countries boost bilateral trade as well as the potential for economic convergence and spillovers through economic exchanges (Hallak, 2006, 2010; Demir and Dahi, 2011; Bergstrand and Egger, 2013; Dahi and Demir, 2013, 2016; Regolo, 2013; Bahar et al., 2014; Fajgelbaum et al., 2015; Cheong et al., 2015; Demir, 2016; Demir and Hu, 2016). Regolo (2013), for example, finds that endowment similarity between country pairs stimulates greater export diversification. Bergstrand and Egger (2013) also find that country pairs of similar economic sizes or capital and labor endowments are more likely to engage in bilateral PTA and investment agreements (BIAs) than others. Bahar et al. (2014) show that having neighbors with similar comparative advantage increases a country's export growth in similar products. Besides, they show that countries with more similar incomes, endowments, and population have more similar exports. Likewise, Hallak (2006, 2010) shows that income similarity increases bilateral trade flows between countries.

4.2.3 Economies of Scale and Market Size Asymmetries

Unlike the discussion in Sections 4.2.1 and 4.2.2, similarities in production and trade structures, consisting (arguably) of primary commodities, are claimed to make it harder to benefit from economies of scale in South–South trade. Faulty government interventions under the ISI through price distortions and errors in the choice of subsidized sectors as well as the geographical location of industrial plants are argued to lower the chances of economies of scale in South–South trade (Schiff, 2003). South–South trade integration is also suggested to have asymmetric effects on trading partners, conditional on their positioning in the industrialization ladder. More advanced Southern countries are more likely to reap larger benefits as they export their lower quality manufactured goods to other less-developed Southern countries. Therefore, weaker Southern countries are claimed to be better off in North–South than South–South trade. Because of economic power asymmetry, industries with the most dynamic development potential are also more likely to relocate to bigger and richer Southern countries, leading to their divergence from the Rest of South (Puga and Venables, 1997; Schiff, 2003; Venables, 2003).

4.2.4 Quality Upgrading

The quality of exported goods is shown to be endogenous to importer characteristics such as income levels or similarities in tastes and preferences. Through panel data on Mexican manufacturing plants, Verhoogen (2008) shows that more productive plants produce higher quality goods to penetrate Northern (particularly United States) markets. This is a stylized fact that was previously highlighted by the structuralist literature as well. Amsden (1989), for example, suggests that South Korean exports to the North enabled product quality upgrades. Hallak (2006), Bastos and Silva (2010), Manova and Zhang (2012), and Dahi and Demir (2016) find that export unit values, signaling product quality, increase with the income levels of importing nations, reflecting increasing consumer demand for quality with income. In fact, Manova and Zhang (2012) show that even the very same firms charge higher prices, reflecting higher quality, in richer country markets. One major implication of these findings is that North–South trade may provide additional benefits through productivity and quality improvements for Southern producers.

4.2.5 Uneven Development, Path Dependency, and Trade

While previously outside the scope of mainstream trade theory, there is now a bourgeoning neoclassical literature emphasizing the importance of initial conditions in explaining long-run differences in incomes and growth (Krugman, 1987, 1991; Lucas, 1988; Becker et al., 1990; Matsuyama, 1991). As Feenstra (1996) pointed out, the assumption of perfect international diffusion of knowledge is a necessary condition for the neoclassical convergence story to materialize. Without this assumption, the same models can lead to convergence clubs within but not between different groups of countries.

Furthermore, Northern colonial rule and slave trade are shown to have had significantly negative effects on bilateral trade, institutional development, democracy, income growth, human capital, trust, and income inequality within the South (Findlay, 1992; Acemoglu et al., 2001; Angeles, 2007; Bagchi, 2008; Iyer, 2010; Wietzke, 2015). Interestingly, the empirical neoclassical trade literature has long been aware of the effect of colonial past on trade as shown by the positive and significant colonial past dummies in Gravity regressions. However, most of these studies do not assume any interdependency between the rise of the West with the fall of the Rest, treating skill-biased technological and structural change in Northern economies as exogenous of their involvement in the South. Furthermore, learning-by-doing and induced-technological change, which have been the corner stones of endogenous growth and new-trade theories, have not been applied to North–South exchanges. As Acemoglu (2015: 456) noted “the orthodoxy …, which ignores the biased and localised nature of technological change, is still widespread in much of macro-economics.”

On the other hand, the structuralist school from its beginnings has questioned the premise that North–South trade is beneficial to all trading parties. Initially developed by Raul Prebisch, the structuralist literature argues that the South exports primary products and/or simple manufactures, in return, for advanced industrial products from the North and therefore remain in a constant state of underdevelopment.Unlike the arguments put forward in section 4.2.3, a rich literature from this tradition shows myriad ways in which North–South interactions create outcomes more favorable to the North, leaving the South in a dependent position to the North (Bacha, 1978; Findlay, 1980; Taylor, 1981; Dutt, 1986, 1987, 1989, 1990, 1992, 1996; Darity and Davis, 2005).

One strain of this literature argues that differences in income elasticities of demand for Southern and Northern goods generate uneven development given the international division of labor whereby the South produces primary products or low-end manufactures with low-income elasticities, while the North produces high-skill-and-technology-intensive goods with higher income elasticities (Prebisch, 1950; Singer, 1950, 1975). Endogenous technological change is also suggested to cause uneven development in North–South trade. The invention of synthetic substitutes for Southern primary goods, for example, is shown to turn the terms of trade against the South, thereby slowing its growth (Dutt, 1996).

The asymmetric nature of North–South trade is also analyzed through the engine of a global growth metaphor where increasing Northern growth moves the terms of trade in favor of the South, stimulating growth and capital accumulation in the South (Lewis, 1980; Taylor, 1981). However, given the structure of Southern and Northern exports, the North–South interaction is doomed to be uneven (Findlay, 1980, 1984; Taylor, 1981; Dutt, 1989, 1990; Darity and Davis, 2005; Ros, 2013, ch. 4). Furthermore, in this framework, Southern growth is always dependent on Northern growth and is not self-sustaining. For example, a positive technological shock in the South increases Southern productivity and growth, leading to an expansion of Southern supply of goods as well as Southern demand for Northern goods, both of which turns the terms of trade against the South. Falling terms of trade, in turn, lowers Southern foreign exchange earnings and profits, eventually slowing down its growth (Singer, 1950, 1975; Prebisch, 1950, 1959; Lewis, 1969; Dutt, 2012). Interestingly, WTO (2003) celebrated the increase in South–South trade in manufactures and financial flows, citing favorably Prebisch's hypothesis on declining terms of trade in the context of discussing the importance of manufactures for industrial growth. Furthermore, the World Bank (2008) pointed out that South–South trade can help reduce the South's growth dependence on Northern growth.

The earlier structuralist literature, however, did not suggest that South–South trade would reverse the asymmetric nature of North–South exchanges. In fact, there is nothing to stop the same dynamics from progressing within the South–South as long as there are the same type of asymmetries between Southern trading partners as is the case today between Emerging South and the Rest of South.

4.2.6 Entry Barriers

Finally, any assessment of the payoff matrix in trade by direction should hold that due to long-standing structural (colonial legacy and neocolonial ties) and policy factors (trade and nontrade barriers), South countries still do not have the same tendency or ease of trade by direction. South–South trade is subject to higher trade barriers, making it more difficult for firms to start exporting, survive and grow in Southern markets. Weak destination institutions, for example, increase entry costs and lower the entry, growth, and survival rates while discouraging firms from exporting to new markets (Anderson and Marcouiller, 2002; Belloc, 2006; Levchenko, 2007; Aeberhardt et al., 2014; Söderlund and Tingvall, 2014; Fernandes et al., 2016). Traditional trade barriers in the form of tariffs are also higher in South–South trade than North–South (Dahi and Demir, 2016). Therefore, North–South trade can offer more opportunities to Southern exporters than those in South–South trade.

4.3 Preferential Trade and Investment Agreements and South–North Exchanges

Asymmetries in bargaining power, knowledge, negotiating capacity, and retaliatory capabilities are argued to bias bilateral trade and investment agreements, favoring the Northern over Southern partners (Thrasher and Gallagher, 2008; Dahi and Demir, 2013, 2016). While these asymmetries are arguably also present in the South–South direction, the gap is smaller, allowing more policy space to developing countries to experiment with economic policies that are most suitable to their needs. An obvious reflection of such asymmetries is that four Northern actors, the United States, the European Union, Canada, and Japan, were responsible for 52% of all trade-related disputes filed at WTO between 1995 and 2015 (Dahi and Demir, 2016, p. 40). The share of low-income countries in total number of complaints was less than 7%, while the middle-income South countries accounted for 45% of the total during the same period (Dahi and Demir, 2016, p. 38). The case with investor-state disputes is no different. Dahi and Demir (2016, p. 47) report that between 1998 and 2014, global South countries were on the defending end 90% of the time, out of a total of 589 disputes filed though international investment agreements (IIAs). Of this number, more than 70% were brought by Northern investors against global South countries (with the remainder launched by other countries in the global South). The threat of a lawsuit works as a deterrent for the South not to employ policies that might be challenged by foreign investors, particularly in the face of exorbitant amounts of awards involved. That is why UNCTAD (2015: 125) argued that IIAs are not “harmless political declarations” and they, in fact, enable Northern investors to “challenge core domestic policy decisions … for instance in the area of environmental, energy and health policies.”

On the issue of trade diversion caused by PTAs, South–South trade is unlikely to be trade diverting from South–North as trade barriers are significantly higher in South–South than in any other direction (Cernat 2001; Kowalski and Shepherd, 2006; Kee et al., 2009; Medvedev, 2010; Dahi and Demir, 2016, ch. 4). Linder (1967) also suggested that the positive effects of South–South trade agreements are less ambiguous than those for the North, and even if they are trade diverting, they were still welfare enhancing as long as the diversion is from the North. Empirically speaking, the biggest trade enhancing effect of PTAs is found in South–South direction (Kowalski and Shepherd, 2006; Dahi and Demir, 2013; Behar and Cirera-i-Criville, 2013). Decreasing cost of intermediate goods imports from other Southern markets can also increase Southern export penetration in industrial goods in Northern markets (Fugazza and Robert-Nicoud, 2006).

As is consistently shown in the empirical trade literature, colonial-link variables almost always appear to be a significant predictor of bilateral trade flows. Therefore, Dahi and Demir (2013, 2016) suggest that PTAs may also be an indirect way of correcting for colonial linkages that distort international trade in favor of North–South direction.10 Obviously, South–South trade suffers from smaller number of such colonial distortions. Dahi and Demir (2013) also see South–South PTAs as a developmentalist tool because of their larger positive effect on manufactured goods exports than North–South PTAs. The international political economy literature on South–South integration also suggested that PTAs and BITs help diversify the alliances of Southern countries and facilitate a more flexible policy space against the Northern dominance in global economy (Hveem, 1999; Hettne, 2005; Doctor, 2007; Thrasher and Gallagher, 2008).

The significant increase in the number of South–South PTAs and BITs suggests that policy makers in the South are aware of their positive effects. The average annual number of new PTA pairs was 30 between 1958 and 1988, it increased to 267 between 1989 and 2013, and 75% of these agreements were in the South–South direction (Dahi and Demir, 2016). In 2013 alone, for example, 222 new country pairs signed PTAs, 66% of which were between Southern countries. Likewise, 88% of BITs were signed after 1990, reaching 3140 by 2015. Of those BITs signed since 1990, 56% were between Southern countries (Dahi and Demir, 2016, p. 47).

4.4 South–South versus North–South Finance

Unlike the extensive literature on trade linkages, theoretical and empirical work on South–South and North–South financial linkages is only very recent and is in much shorter supply. The main reason is the relatively more recent history of such exchanges, which started to grow mostly after the financial liberalization wave of the early 1990s. The data quality and availability issues are also more severe for financial flows than trade flows. Most existing work on the topic has focused on long-term capital flows as FDI differs significantly from other types of financial flows in its effects on productivity, capital formation, growth, and employment. Global FDI flows reached $1.8 trillion in 2015 up from $54 billion in 1980 and $205 billion in 1990 (UNCTAD, 2017a). Even more strikingly, an increasing percentage of these flows is now to and from the South, and increasingly within the South–South direction. While more than 80% (90%) of all inflows (outflows) were to (from) the North even back in 2000, almost 60% (40) of all were to (from) the South in 2014. Mainland China alone ranked number 3 in both FDI inflows and outflows in 2015. Furthermore, 8 of the top 20 host economies and 6 of the top 20 home economies were from the South in 2015. Within aggregate FDI flows to the South, South–South flows increased significantly, reaching around 63%–65% of all outflows from developing countries in 2010 (UNCTAD, 2011; World Bank, 2011). In the case of Africa, for example, 78% (44%) of all announced greenfield FDI inflows and 94% (88%) of outflows were in South–South direction in 2016 (2015). In Asia, 50% (52%) of all announced Greenfield FDI inflows and 82% (79%) of all outflows were in South–South direction in 2016 (2015) (UNCTAD, 2017b. pp. 45, 50).

Within the neoclassical framework, North–South capital movements, particularly FDI flows, facilitate technology transfer and productivity spillovers, allowing the South to catch up with the North. The predicted spillover effects include better technology, modern management techniques and managerial skills, R&D investment, and more experience in international markets as well as the possibility of learning by watching (Fosfuri et al., 2001; Fabbri et al., 2003; Navaretti et al. 2003; Almeida, 2007; Desai et al., 2008; Huttunen, 2007; Arnold and Javorcik, 2009). As the productivity and knowledge gaps are larger in the North–South dimension, so are the expected spillovers effects.

And yet, as discussed in Sections 4.2.1 and 4.2.2, institutional and cultural similarities as well as closeness in technological and preference structures between countries can affect the potential for spillovers and convergence through economic exchanges (Bergstrand and Egger, 2013; Regolo, 2013; Bahar et al., 2014; Cheong et al., 2015). Recent work on Linder hypothesis suggests that South–South FDI may offer some additional benefits over North–South FDI. Fajgelbaum et al. (2015), for example, show that countries with similar incomes and development levels are more likely to receive FDI from each other, given their similarities in consumer tastes and preferences. And yet, Demir and Duan (2017) find no evidence of positive productivity growth or convergence effects from bilateral FDI flows in South–South, North–South, South–North, or North–North directions.

Financial development asymmetries between trading partners can also contribute to the uneven pattern of development in South–North trade. Kletzer and Bardhan (1987), Rajan and Zingales (1998), Demirguc-Kunt and Maksimovic (1998), Beck (2002), Svaleryd and Vlachos (2005), and Hur et al. (2006) argue that credit-market imperfections cause differential comparative costs even with identical technologies and endowments and therefore industries that are more dependent on external finance such as those in capital intensive sectors grow faster in countries with better developed financial systems. In an extension of this work, Demir and Dahi (2011) argue and provide empirical support to the hypothesis that the comparative disadvantage of the South against the North in financial development can be alleviated in South–South trade where such asymmetries are smaller. As a result, a financially underdeveloped Southern country can have a better chance of exporting higher skill-and-technology-intensive products that are more reliant on external finance to other Southern countries.

South–South trade is also argued to be less sensitive to exchange rate shocks than South–North trade. Caglayan et al. (2013) suggest that because of lack of financial development as well as the original sin problem in the South, exchange rate shocks affect Northern and Southern exporters differently. In an extension of this work, Caglayan and Demir (2016) explore the effects of exchange rate changes on trade flows after controlling for the skill-content and origin/destination of products. They report that higher skill exports are the least affected product category from exchange rate movements, thus affecting Southern and Northern economies differently. Furthermore, they find that while South–South and South–North exports are significantly affected by exchange rate shocks, North–South exports are not.

Regarding South–South capital flows, recent empirical work suggests that Southern investors have a comparative advantage in operating in institutionally less developed and higher risk countries (Cuervo-Cazurra and Genc, 2008; Darby et al., 2010; Aleksynska and Havrylchyk, 2013; Demir and Hu, 2016). Therefore, this advantage can help Southern investors overcome their disadvantaged position in technology, operational and management capabilities, experience, internal and external financing sources, marketing, size, and colonial linkages (i.e., their lack of it), and enable them penetrate Southern markets (Dahi and Demir, 2016; Demir and Hu, 2016). Likewise, less developed Southern host countries can have less restricted access to foreign capital through Southern multinationals.

On the more critical side of the literature, increasing South–South financial flows is blamed for undermining Northern country efforts to improve Southern institutions as they have weaker institutions and conditionality requirements (Lyman, 2005; Economist, 2006; Graham-Harrison, 2009; Mbaye, 2011; Warmerdam, 2012; Strange et al., 2013). In contrast, North–South FDI is expected to improve Southern institutions as the Northern investors are endowed with better institutions than Southern ones (Mauro, 1995; Hall and Jones, 1999; Kaufmann et al., 1999; Acemoglu et al., 2001, 2005; Alfaro et al., 2008). Directly through conditionality requirements, such as anticorruption or better rule of law demands in PTAs and BITs, or indirectly through the demonstration channel, (i.e., the introduction of new methods of business practices), Northern investors can help improve institutional quality in the South (Kwok and Tadesse, 2006). Northern investors can also improve host country institutions through lobbying and exerting pressure on local policy makers (Dang, 2013; Long et al., 2015). Yet, Demir (2016) finds no evidence of positive institutional effects of FDI flows at the bilateral level in North–South or any other direction but reports some negative effects at the aggregate level for South–South flows.

Table 3 provides a summary of the literature on South–South and South–North exchanges in trade and finance that we discussed in Section 4.

Table 3. Classification of South–South Theories (Mainstream and Heterodox)

| 1. In favor of North–South trade and finance | |

| 1.1 Static Theories | |

| Diaz-Alejandro (1973), Krueger (1977), Baldwin (1979), Khanna (1987), Deardorff (1987), Havrylyshyn and Wolf (1987), Bhagwati et al. (1998), Panagariya (2000) | Allows for specialization, technology transfer, and comparative advantage. |

| 1.2 Dynamic Theories | |

| Otsubo (1998), Schiff (2003), Schiff et al. (2002), Schiff and Wang (2006, 2008) | Expansion of intra-industry trade. Increases TFP through faster and better technology diffusion. It also enables economies of scale. |

| Puga and Venables (1997), Venables (2003), Schiff (2003). | South–North is better for smaller/weaker Southern countries as they are disadvantaged in economic power and market size against larger Southern countries. |

| Krugman (1995) | Allows for vertical specialization/value-chain fragmentation |

| Hallak (2006), Bastos and Silva (2010), Manova and Zhang (2012), Dahi and Demir (2016) | Export unit values (product quality) increase in importer incomes, allowing for productivity and quality improvements. |

| Anderson and Marcouiller (2002), Belloc (2006), Levchenko (2007), Aeberhardt et al. (2014), Fernandes et al. (2016), Söderlund and Tingvall (2014) | Lower Northern entry barriers make it easier for firms to export, enter, diversify, survive, and grow. |

| Fabbri et al. (2003), Fosfuri et al. (2001), Almeida (2007), Desai et al. (2008), Arnold and Javorcik (2009), Navaretti et al. (2003), Almeida (2007), Huttunen (2007) | FDI spillovers through better technology, modern management techniques and managerial skills, R&D investment, more experience in the international markets, and higher possibility of learning by watching. |

| Lyman (2005), Kwok and Tadesse (2006), Graham-Harrison (2009), Warmerdam (2012), Dang (2013), Long et al. (2015), Mbaye (2011), | North–South FDI and financial flows improve Southern institutional quality through conditionality requirements, lobbying, and demonstration channel. South–South financial flows encourage rogue states and hurt institutional development efforts in the South. |

| 2. In favor of South–South trade and finance | |

| 2.1 Dynamic Theories | |

| Linder (1967), Hallak (2006, 2010), World Bank (2006), UNCTAD (2011, p. 42), Bergstrand and Egger (2013), Regolo (2013), Amighini and Sanfilippo (2014), Cheong et al. (2015), Bahar et al. (2014), Cheong et al. (2015), Fajgelbaum et al. (2015), Demir and Duan (2017) | Similarities in institutions, culture, endowments, production structures, preferences, incomes, and technological development increase bilateral trade and finance and boost facilitate economic convergence and spillovers. They also allow for easier technology adoption and enable Southern investors to address local consumer needs better. |

| Dutt (1989, 1990), Findlay (1980, 1984), Taylor (1981), Darity and Davis (2005), Lewis (1980), Taylor (1981), World Bank (2008), Ros (2013, ch. 4), | North–South trade causes dependent growth in the South. South–South exchanges allow for decoupling from Northern business cycles and increase global economic stability. |

| Cuervo-Cazurra and Genc (2008), Darby et al. (2010), Aleksynska and Havrylchyk (2013) | South–South investment flows can benefit from the comparative advantage of Southern investors in operating in institutionally less developed and more risky countries. |

| Amighini and Sanfilippo (2014), Demir and Hu (2016) | |

| Prebisch (1959), Akamatsu (1962), Amsden (1980, 1983, 1984, 1987, 1989), Fugazza and Robert-Nicoud (2006), Amighini and Sanfilippo (2014), Dahi and Demir (2013), Demir and Dahi (2011) | Higher skill and technology-intensive content of South–South trade allows for better skills upgrading and endogenous technological change. Allows for more export diversification and higher skill content in exports. |

| Amsden (1980, 1987), UNIDO (2005), Caglayan et al. (2013), Regolo (2013), Dahi and Demir (2013), Stewart (1982, 1992, p. 81), Kaplinsky (1990), Bhalla (1985), Nelson and Pack (1999), Schumacher (1973), Atta-Ankomah (2014), Lall (2000, 2001), Pack and Saggi (1997), Lall et al. (1989), Copeland and Kotwal (1996), Murphy and Shleifer (1997), Agyei-Holmes (2016), Atta-Ankomah (2014), Xu et al. (2016), He et al. (2012), Demir and Duan (2017) | The North controls the direction of technological innovation, which is conditioned by Northern endowments and preferences, making it more capital-intensive. Southern technologies are better fit for production and demand structures, resource bases, institutions, factor endowments, and market size in the South. They are more cost-effective and easier to learn, adapt, and upgrade. They are also more fit to consumer preferences. |

| Hveem (1999), Hettne (2005), Doctor (2007), Thrasher and Gallagher (2008), Kaplinsky (2008), Gallagher et al. (2012), Dahi and Demir (2013, 2016), UNCTAD (2015) | Smaller gaps in bargaining power, negotiating capacity, and retaliatory capabilities allow for more balanced BITs and PTAs and create more flexible policy space |

| Myrdal (1956), Kowalski and Shepherd (2006), Demir and Dahi (2011), Dahi and Demir (2013, 2016), Behar and Cirera-i-Criville (2013) | Higher trade and skill-growth effects of South–South PTAs |

| Caglayan et al. (2013), Caglayan and Demir (2016) | South–South trade may be less sensitive to exchange rate shocks |

| Brautigan (2009) | Chinese lending lowers corruption risk in Southern countries. |

| 3. Critical of North–South exchanges | |

| Singer (1950, 1975), Prebisch (1950, 1959), Bacha (1978), Taylor (1981), Dutt (1986, 1987, 1989, 1990, 1992, 1996, 2012), Findlay (1980), Darity and Davis (2005), Acemoglu and Zilibotti (2001), Acemoglu (2015) | Causes uneven development favoring the North through terms of trade changes, dependent growth, and skill-biased technological change. Hurts industrialization efforts by forcing South to specialize in primary and labor intensive goods. |

| Acemoglu et al. (2001, 2015), Iyer (2010), Wietzke (2015), Bagchi (2008) | Northern colonialism and slave trade had negative effects on institutional development, democracy, income growth, human capital, trust, and income inequality in the South. |

| 5. Critical of South–South exchanges | |

| Kaplinsky et al. (2007)), Jenkins (2009), Brautigan (2009), Gallagher and Porzecanski (2008, 2010), Giovanetti and Sanfilippo (2009), Adisu et al. (2010), Kaplinsky et al. (2010), Jenkins and Edwards (2006, 2014), Peters (2005), Jenkins and Peters (2009); Ros (2013), Cabral et al. (2016), Dahi and Demir (2016), Demir and Duan (2017), Shankland and Gonçalves (2016), Scoones et al. (2016) | South–South exchanges benefit Emerging South at the expense of Rest of South. Rise of China crowds out Southern exporters and cause primarization and deindustrialization. |

| Amanor and Chichava (2016), Cabral et al. (2016), Scoones et al. (2016), Demir and Duan (2017) | South–South technology transfer and adaptive capabilities are subject to same limitations as North–South exchanges. |

| Baah and Jauch (2009), Jauch (2011) | Chinese investments in Africa are neocolonial, focusing on resource extraction, and are antilabor and exploitative. |

| Mohan and Kale (2007), Mohan et al. (2014), Mohan and Lampert (2013), Demir (2016), Demir and Duan (2017) | The net effect of Southern investments in local economies depends on country characteristics. |

5. China and the Emerging South in Africa

The increasing importance of South–South exchanges in trade and finance is most visible in the China in Africa literature, which brings together the complex intersection of trade, aid, FDI, migration, and geopolitics. We dedicate a separate section here for several reasons. First, compared to other debates on South–South exchanges, interactions between China and various African countries have received particular attention in North America and Europe. In addition, China and Africa tend to represent opposite ends of the development spectrum, that is, a rising industrial power versus a relatively agrarian and primary good exporting region. Furthermore, on many development accounts, Africa appears as a net loser from the neoliberal period, while China appears as a winner. This makes investigating the outcome of their increased interaction particularly compelling. Finally, China in Africa best illustrates how the academic literature has evolved to allow for greater complexity in analyzing South–South interactions.

The earlier literature on the topic tended to be simplistic. As Ado and Su's (2016) survey argue, “research publications on the Chinese in Africa are mostly oriented toward findings that highlight a win-lose paradigm” (p. 42), underscoring the ideological bias in some of this literature, as is also pointed out by Power et al. (2012). Following Kaplinsky (2013), we classify the China in Africa debate by the levels of complexity of “China” and “Africa” as analytical categories that highlight the dynamism and the heterogeneity of country experiences involved therein. Particularly, we suggest three analytical categories: (a) China and Africa as two homogeneous actors whose interactions would either benefit or harm the other or both; (b) recognizing Africa as too heterogeneous and diverse to expect a unitary impact of Chinese presence, and to (c) a most complex approach, which recognizes that both China and Africa are heterogeneous with multiple actors, processes, and impacts. The articles surveyed here are classified accordingly in Table 4. The main benefit of this classification is that it reveals not just the fact that China–Africa engagement is complex but how it is complex.

Table 4. Selective Survey of China–Africa Literature by Complexity

| 1. Both China and Africa as homogeneous | |

| Brautigan (2009) | Chinese aid and investment is largely beneficial. |

| Alden (2007) | China as competitor, partner, colonizer: elements of all three, but large positive potential. |

| Busse et al. (2016) | Positive terms of trade impact, crowding out of African firms and no impact of aid and FDI on African growth |

| 2. Africa heterogeneous, China homogenous | |

| Kaplinsky et al. (2007)), Kaplinsky (2008), Adisu et al. (2010), Brenton and Walkenhorst (2010), Kaplinsky et al. (2010), Edwards and Jenkins (2014) | Channels of impact: trade, aid, FDI reflecting strategic, and political economy factors. China endangers manufacturing, governance, and institutional development, triggers resource-curse, crowds out domestic investment, and has limited local employment effects. |

| Jenkins and Edwards (2006) | Direct channels more important than indirect due to lack of export similarity between China and SSA |

| Aguilar and Goldstein (2009) | China in Angola increases Angolan engagement with international community and brings significant infrastructural investments. |

| Baah and Jauch (2009), Jauch (2011) | Chinese investments engage in neocolonial practices and labor exploitation. |

| Xu et al. (2016) | Positive effects of Chinese aid on technology transfer. |

| Atta-Ankomah (2014), Agyei-Holmes (2016) | More appropriate technology transfer through more labor-intensive, cost-effective, and profitable imported capital goods. |

| Cheru (2016) | Joint ventures of China in Ethiopia and the use of the country as launching pad for regional investments. |

| 3. Both China and Africa as heterogeneous | |

| Kaplinsky (2013) | Multiple actors in both China and Africa, indirect effects just as important as direct ones, and interaction contains both equalizing and unequalizing tendencies. |

| Mohan and Lampert (2013) | Labor exploitation and migrant worker integration varies by Chinese firm, country, institutional, cultural, and other factors. |

| Strauss and Saavedra (2009) | Ethnographic studies showing how cultural norms, structures, practices, critical engagements, and other interactions over time shape the China–Africa relationship. |

| Cabral et al. (2016), Amanor and Chichava (2016), Shankland and Gonçalves (2016) | Chinese and other Southern investment in Africa are subject to the same types of constraints and bottlenecks present in North–South exchanges. |

Source: Kaplinsky (2013) and authors.

As alluded to by Power et al. (2012), China's Africa presence is often interpreted by its Cold War era engagements, signified by the iconic Tanzania-Zambia Railway, built during 1970–1975, which contained several elements that were later erroneously considered as new in terms of China's current engagement in Africa. First, it was a massive investment, costing about $600 million dollars, more than the Aswan dam in Egypt had cost the Soviets. Second, it was efficiently and rapidly done. Despite containing 300 tunnels, 10 km of bridges, and covering a distance of 1860 km, it was completed in only five years and two years ahead of schedule. Third, it contained a large number of workers, many of whom were Chinese (of the 75,000 workers who worked on the project, 25,000 were Chinese, and the remaining were Tanzanian). These three elements: massive infrastructure project, efficiency in implementation, and the presence of Chinese laborers are common tropes covered by the later literature.

The first wave of the China in Africa literature was born in reaction to the overwhelmingly alarmist discussions in the West. Some, if not all, of this literature was excessively optimistic, highlighting the benefits more than potential risks (Alden, 2007; Mawdsley, 2008; Brautigan, 2009; Chan, 2013; Kachiga, 2013). Brautigan (2009) questions the “myths” on China in Africa by arguing that contrary to Western aid, Chinese aid and concessionary loans reduce the possibility of corruption and embezzlement in host countries as they are often contracted directly through Chinese companies. Likewise, Alden (2007) assesses China–Africa policy through three possibilities that are partner, competitor, and colonizer, and finds elements of each in this relationship. While he finds that Chinese presence provides significant infrastructural benefits, it may also undermine African local industrial development and hurt indigenous democratization efforts. Jenkins and Edwards (2006) examine the direct and indirect impact of both China and India on African development in both natural resource and textile sector and find only limited crowding out effect on African exports in third country markets.

Kachiga (2013) through case studies on Nigeria, Sudan, Angola, Zimbabwe, and South Africa illustrates both the unique aid and investment strategies of China and how they compare and differ from those of the West. Like Western aid, Chinese aid comes with conditionalities and expectations of strategic payoffs, including tying them to purchases of Chinese goods and services. Nevertheless, given China's principle of sovereignty and noninterference, Kachiga argues that China's aid more closely fulfills the meaning of the word than that from the West as African countries are freer to set their own priorities on spending aid money. Carmody (2013), focusing on the BRIC countries, also highlights the positive developmental effects of these countries’ involvement in Africa.

Kaplinsky et al. (2007)), Kaplinsky (2008), and Kaplinsky et al. (2010) provide a more critical and balanced analysis of China effect in Africa. Kaplinsky (2008) is a cornerstone of the second level of complexity of China in Africa studies and finds that China may be undermining industrial development in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) through two channels. First, increasing Chinese imports of natural resources turns the terms of trade against manufacturing.11 Second China's manufacturing growth is outcompeting African manufacturing, which has direct as well as indirect effects through third countries. For example, China's trade with the United States may help or hinder SSA exports to the United States. In addition, high saving rates of China help lower global interest rates and stimulate investment in SSA. Finally, increasing Chinese participation in international financial institutions may help relax their conditionality requirements imposed on SSA in aid flows given that China has now become a major donor for aid to the South (Gallagher et al., 2012; Strange et al., 2013).