Animation is an entertainment medium like no other. It offers extraordinary flexibility, as each part of its process can be handled and controlled by the creator. It operates using a different (but recognizable) vocabulary from that of live-action film, enabling different forms of expression to exist in a space for an audience to engage with. As such, it permits new versions of worlds or environments for films, giving tremendous creative freedom for writers, artists, animators, directors, and producers to transport audiences to different dimensions of “reality,” which seem real but are in fact imagined.

This chapter examines the contribution that early planning and scriptwriting play in this creative freedom. It establishes how the preproduction phase of an animated project is planned, managed, and delivered by people with differing job roles in the production’s life cycle. It also explores the importance of scriptwriting—including different approaches and development—as one of the first possible starting points in preproduction.

Planning a script involves writing and rewriting as the outline plot begins to evolve.

The animation pipeline in preproduction

As outlined in the Introduction, the preproduction phase of the animation pipeline involves the exploration of scripts, visual and sound concepts, and ideas, and their testing through research in order to prepare material before filming and recording.

Preparing a tangible framework for this phase is essential, as this governs the budget, the scheduling of the technical pipeline arrangements, and the managing of the workflow arrangements of the crew in the studio. The hard work done at this early stage permits greater creative risks to be taken in preproduction. Careful planning allows animators, storyboarders, scriptwriters, composers, musicians, special-effects creators, and designers to fully explore the subject.

This creative freedom for concept selection and idea origination, development, and execution is crucial to the whole project, and a thorough grasp of the subject will positively affect the quality of the final output. Creating the right conditions for ideas to flourish is essential, especially those centered on the core animation properties of performance, movement, and narrative. Establishing a clear set of parameters is a key exercise in helping to plan, structure, and manage the project (see box opposite), and this good preparation and planning will almost certainly deliver the project on time and on budget—two essential considerations in the world of animation.

It is essential to ask the following questions, or variations thereof:

• Has the project been approved?

• Who is the project for and what is its intended outcome?

• Who is the target audience?

• Who is funding and/or supporting the work?

• Is there a budget and if so, what is it?

• Who controls the budget?

• What is the time frame in which the project needs to be conducted?

• How much time is allowed for research for the project?

• How is the time frame split between phases of preproduction, production, and postproduction?

• Who has responsibility for making final decisions?

• Is there sufficient scope in resources or budget for a crew?

• What should the crew be made up of?

• Who owns the project once the production is completed?

• Who is responsible for designing the content and style of titles?

• Are there any cultural, social, or philosophical issues with the proposed content that require legal clearance?

• Are there any special considerations that need to be given for audiences with particular needs and requirements?

• Who owns the rights for any associated materials that could be developed in the future?

• What happens if the project is canceled?

• How will the project be delivered?

• What is the broadcast format for the project?

• How will the finished animation be distributed?

• What technical and physical resources are available and are there extra funds available for this?

• Are there associated production values (material to be gained for documentary or promotional purposes) that need consideration?

Implicit in the planning process is the need to understand the variety of jobs involved in creating an animated project, what each job entails, and at what stage these roles operate, either independently, jointly, or collectively across the whole production. Members of the crew need to know and understand their roles from the outset. In a feature film or television series, roles are clearly defined and animators may often be hired by a studio to establish or supplement teams. In independent productions, an individual may undertake a number of roles simultaneously, depending on the size of the crew and the size of the budget, in order to see the production through from concept to completion.

The director is in charge of the production, including overseeing storyboarding, development, and production of the animated work.

An organized studio environment creates a productive and efficient workplace, even if the building was formerly a local bank, illustrated by Nexus Productions in London.

Preproduction:

Director—person in charge of the production, including overseeing storyboarding, development, and production of the animated work.

Producer—works closely with the director, supervising, and controlling the teams at various stages of production and postproduction to bring the project in on time and on budget.

Art director—responsible for the intrinsic look of the project and for communicating this vision to the production teams.

Film editor—works closely with other members of the core team to review and edit passages and combinations of prepared animated sequences so as to tell the story most convincingly.

Production supervisor—liaises with the director and producer to manage the project and ensure teams are prepared to pass and receive work through phases of production.

Supervising animator—works closely with the director and producer of the project and is a vitally important link between their vision and the animation team’s ability to create it.

Researcher—can work individually or as part of an organized team, unearthing contacts, investigating story leads, and collecting reference material for the preproduction and production teams.

Story:

Story supervisor—makes sure that the script or story is being followed, checking for accuracy with any factual events.

Story coordinator—provides the link between the storyboard artists and the supervisor.

Storyboard artist—responsible for problem solving, planning, and visualizing how early script ideas and concepts might be realized.

Animation:

Directing animator—sometimes known as “lead animator,” this is generally a senior animator who has experience of previous productions and is able to manage the collaborative team of animators.

Animator—an artist who understands the principles of imagined movement and creates multiple frames of images using various techniques.

Art:

Art manager—responsible for coordinating the smooth running of the animation art department.

Picture researcher—collects important contextual visual material to aid the art department in its creation of sets, props, and characters.

Conceptual artworker—brings initial ideas to life, working quickly to visualize concepts often while ideas are being verbally discussed. Designer and illustrator—work closely with the animators to design and create backgrounds, sets, and props to support the production.

CG painter and designer— a technical artist who works digitally to originate, develop, and enhance artwork for production, often using drawing tablets and working on screen.

Sculptor—an artist who translates two-dimensional drawings into usable and sometimes functioning three-dimensional forms, from maquettes to fully formed sculptural models.

Character designer—researches, originates, develops, and executes the design for characters in both human and object form.

Props designer—responsible for the creation of props that characters will use on set.

Set designer—responsible for the environment of the project; works carefully with the lighting designer and camera team to ensure sets are convincing but also accessible and functional in the production phases.

Layout:

Layout manager—receives approved storyboards, and is responsible for briefing and managing the layout artists so that they remain faithful to the spirit of the storyboards and the director’s vision.

Supervising layout artist/ designer—like the supervising animator, this is a role reserved for a senior member of the layout team who has experience of bringing conceptual artwork as stills and sequences to fruition in the layout phase of production.

Layout artist—responsible for developing the storyboard images into highly finished visuals and/or full camera-ready artwork, depending on the animation treatment chosen for the feature.

Set dresser—works closely with the set designer, ensuring that his or her vision is expressed through the variety and attention to detail of the chosen material properties of the set.

Editorial:

Editorial manager—takes control of the story, ensuring that there is continuity between script and artwork, pointing out inaccuracies, and bringing teams together to find solutions in the preproduction phase.

Assistant editor—supports the editorial manager in his or her role by acting on decisions taken and making sure the production teams communicate well with each other.

Editorial production assistant— provides administrative support for the editorial and postproduction departments of a studio.

Storyreel music editor—has the responsibility of ensuring that the initial sequential material is accompanied by a basic soundscape, which might be actors reading from scripts or a “rough cut” of a proposed soundtrack.

Camera Team:

Camera manager—takes charge of how scenes can be filmed by liaising with the director and the producer and communicating these decisions back to the camera team.

Supervisor—ensures that the camera manager’s instructions are followed in the studio.

Engineer—operates the cameras and ensures parity between the intended shots and what might be physically possible in the studio environment.

Technician—prepares, maintains, and services the cameras before, during, and after production to ensure a fully functioning set.

Calibrator—makes sure that digital monitors are calibrated at regular intervals to ensure consistency and parity in sequential work.

Production:

Production controller— responsible for ensuring that preproduction material is processed on time and on budget through the production process.

Accountant—ensures that the project is kept on budget by managing salaries, expenses, and remuneration for costs incurred in production.

Purchasing/Facilities manager— person charged with making necessary decisions and purchases to allow the project to come to fruition.

Production coordinator— supports the production controller by acting on decisions made and communicating these with the appropriate teams.

Production schedule coordinator— holds regular meetings with the production teams to review progress and coordinates changes to keep the schedule on track.

Marketing/Promotion coordinator—works with the production schedule coordinator to collect, review, and select supporting material from the project that can be used to market and promote the project ahead of its intended release.

Supervising sound editor— coordinates the various aspects of sound production.

Sound-effects editor—coordinates the gathering, appropriation, and implementation of sound effects used in the production.

Sound designer—includes all aspects of sound in an animated production not composed by musicians.

Sound editor—decides what sounds should be incorporated to support musical scores or interludes.

Computer Systems:

Computer system manager— oversees the digital technical production facility.

Hardware/Software engineer— operates and maintains computer hardware and software being used in the feature’s production.

Logistics—responsible for moving sets, props, and project materials in or between studios if filming is happening at another location.

Technician—provides technical support to the engineers by testing and repairing equipment and making sure all aspects of the technical production process work effectively.

Media systems engineer— responsible for the design, installation, and maintenance of the digital infrastructure underpinning computer-generated imagery (CGI) studio productions.

Modeling and animation system development—usually work as a team to develop software and hardware systems, either pre-empting or responding to technical issues that might arise or have arisen during the production process.

Postproduction supervisor— sometimes known as a “technical director,” this role ensures that the completed animation is produced and packaged for distribution.

Re-recording mixer—checks and mixes recordings of dialogue, sound effects, and scores to ensure parity between sound and vision.

Foley editor—named after the famous Hollywood practitioner Jack Foley, who was an early exponent of the art, the foley editor’s job is to decide what sound effects need adding in postproduction to artificially enhance an action, and to work with foley artists to achieve these effects.

Foley artist—a skillful job that requires a good ear for sounds and the ability to imitate them imaginatively through sometimes unconventional and unexpected devices.

Foley recordist—works with the foley artist to capture sounds that can be used to enhance effects not possible using conventional recordings.

Casting consultant—plays a pivotal role in understanding the director’s vision of what encapsulates the core credentials of each character that will require a voice to be cast, and acts as an important liaison between the studio and casting agents and actors.

Voice casting agent—represents actors whose voices are sought to read scripts and record dialogue for created characters.

Music:

Music editor—has the responsibility for compiling, editing, and synchronizing the musical score in production and ensuring that the musical sound landscape is correctly processed in postproduction.

Production sound mixer— member of the crew responsible for collecting all sound recordings, including deliberate and accidental sounds captured both in the studio and even on location that could later be utilized by the foley artists.

Music production supervisor— fosters the relationship between musical and visual parts of the production by selecting and licensing music used.

Orchestra contractor—works in a communication and enactment capacity in selecting orchestras that are able to perform musical scores, interludes, and anecdotes as directed by the composer or music production supervisor.

Recording assistants—create high-quality studio recordings of the orchestral and other musical works that will become part of the production’s score.

Dialogue recorders—capture sound recordings of actors reading parts for different animated characters.

Title Design:

Color timer/grader— responsible for re-grading film stock by altering, enhancing, or subduing its appearance using photochemical, electronic, or, more commonly, digital processes.

Negative cutter—works closely with the editor to cut film negative precisely to be identical to the final edit. Traditionally, the film is cut using scissors and repaired using a film splicer and film cement. In recent years, the arrival of digital intermediates means that the skills of the negative cutter have been used to lift selected takes from rushes and composited to reduce the amount of digital scanning required.

Title designer—is responsible for designing the opening and closing titles and credits for the production.

Distribution:

Distribution manager—works with other distribution networks, providers, and agents to negotiate international distribution rights to the production.

Distribution agent—works on behalf of distribution networks and media broadcast organizations to win contracts to show productions globally.

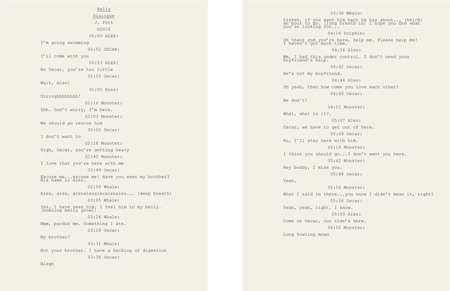

The simple but imaginative script for Skype enabled director Grant Orchard to play with visual and aural elements to illustrate the immediate and user-friendly nature of the product for consumers.

Scriptwriting

Animation as a form enables a multitude of ways of thinking about and describing narratives. It can bring historical and contemporary stories to life, embellishing and heightening our appreciation and enjoyment. In order to use animation as a storytelling vehicle, creators must decide where the root of content is to be found. A script is one starting point, but it is equally possible for some animated productions to exist without a script, the director instead preferring to use the storyboard as a visual scripting device, especially where there is no fixed dialogue or narration attached to a particular shot.

Although animation shares some of the narrative conventions of live-action film, such as the composition of scenes or the structuring of shots to tell stories or explain ideas, writing for animation requires some particular considerations that emerge out of the distinctive nature of the form itself. First, unlike live action, animation is not bound by the constraints of physical forces and limitations, such as gravity or conventional human movement. Second, the process of making an animated production is elemental. Sections are effectively pieced together and reviewed as a production grows, thereby granting flexibility to change the script to enable scenes or sections to be filmed, or edited, which can better explain a plot or idea. Understanding and appreciating that there are different approaches to writing for animated productions is important and the rest of this chapter examines what a script is, why it is written, and how it informs the production.

What is a script?

A “script” is a document that details the “plot” of an animated production in written form allowing a story to be told. Structurally, a script is broken down into smaller consecutive sections called “scenes.” Each scene outlines the main action chronologically, including fundamental details such as who is speaking and what figurative actions or gestures are accompanying their speech. It might also include details such as forthcoming actions, musical interludes, narration, or sound effects to support the storytelling. The script allows the director the opportunity to interpret the story by utilizing distinctive visual and aural processes and gives the producer a clear rationale about how the production will be finally pieced together for release and distribution. More broadly, the script enables an animator to plan how to dramatize actions detailed in each scene in preproduction, and to create these dramatic movements when the project goes into production.

British animator and illustrator Julia Pott created a simple script that permitted her to use animation to externalize bubbling internal emotional reactions in her animated film Belly (2011).

The script helps establish a rhythm and pace in telling a story or can explain an idea through particular events or “beats.” Creating a written rhythmic feel to the script is a highly individual process, and writers develop their own writing traits that allow them to specialize in different spheres of animated productions. Scriptwriters also originate and develop stories in certain styles, just in the same way that animators can utilize different visual production techniques and processes to elicit different responses from the target audience. Some scriptwriters prefer to write alone, while others like to bounce off story ideas and developments as part of a writing team.

In his book Scriptwriting (2007), Paul Wells proposes four different models of writing that are useful when thinking about the origins and development of an animated script: traditional scriptwriting for animation, studio-process script development, series-originator writing, and creator-driven writing and/ or devising. Each approach is valid, but will depend on the composition and working arrangements of the team involved with a project. Traditionally, scriptwriting for animation has involved the scriptwriter (or scriptwriting team working with a script editor) devising a textual script, using processes common to live-action scriptwriting for use in animated feature films or television series. More recently, a studio-process script development model has become more popular, where an in-house studio visual creative team develops a script in response to a brief or an idea, using supporting developmental tools and processes such as a storyboard, sketches, character designs, and animatics.

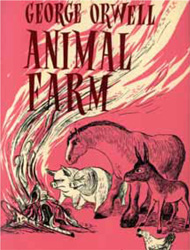

Working from George Orwell’s 1945 novel Animal Farm, the production team at Halas & Batchelor make decisions on how the text should be adapted for screen.

Other approaches include the series-originator writing method, where a “bible” is created by the production team for an animated series, containing central information regarding characters, storylines, and plots that can act as a core compendium for writers hired to work on the series but who perhaps will contribute ideas from a distance. Finally, the method of delivering a script using creator-driven writing and/or devising exists where an individual or a creative team develops material for independent productions using unorthodox methods, including bullet-pointed plot ideas.

As a general rule, a script is originated and developed by the scriptwriter (or writing team), together with a script editor, director, and producer, to explore ideas for the animated production. Developing a script involves constantly writing and revising the written approach. The finished script is known as a “treatment” and represents the culmination of a writing journey that continually originates, develops, executes, tests, and rewrites material until a satisfactory conclusion is reached, and which allows the production to take account of different directional, artistic, and technical points of view. Scripts can be developed for months or even years before being given the “green light” to go into production. They are increasingly used in animated feature films to help secure finance from outside investors in conjunction with a “pitch” (see pages 64–66) and are a vital bridge in attracting and securing the services of actors for voice-over recordings as the production progresses.

The script from director Chris Curtis’s A Day in the Life of an Audi Driver includes specific details regarding the commissioning client, running time of the advertisement, and format, as well as rhythmically breaking up sections of the script to provide a pace to the narrative.

The vocabulary and language of animation

The range of possibilities afforded by the medium of animation becomes particularly apparent when thinking about the vocabulary and language of the form. Animation can establish, utilize, and promote a particular vocabulary in addition to that found in live-action film, helping to better describe, and inform the audience of, ideas and plot lines. This vocabulary includes the use of exaggeration and transformation, symbolism, penetration, controlling the elements of speed and time, depicting histories and predicting futures, and portraying the invisible or unexplained.

Having the scope to exaggerate or transform narrative storytelling ideas through a process of highlighting and promoting them, allows the writer to control their impact. In animation this is a very useful tool as there is greater opportunity to accentuate or diminish actions, movements, and sequences. Similarly, the ability to use symbolism both permits the description of “invisible” forces, such as satellite tracking or waves of sound or heat, and focuses an idea for an audience—for example, a rising bump on the head of a character who has just been hit by an object, expressing obvious and tangible pain.

Chris Shepherd’s film, Dad’s Dead (2002), inventively uses a mixture of animation and live action, allowing the viewer to veer between reality and imagination by posing dark and subversive questions in an otherwise familiar environment.

The term “penetration” acknowledges the capacity of animated material to effectively delve into and hunt around particular objects—for example, a human eye—taking the viewer on an unexpected journey around and through the inner workings of the object to explain its structure and purpose. Of arguably greater magnitude still, the facility to control the speed and time of actions opens up huge possibilities for the scriptwriter, enabling centuries to be collapsed into a few seconds of footage, or split-second reactions to be drawn out, investigated, and explained. Depictions of unseen events, whether they are historical or have not yet happened, or are perhaps invisible or unexplained, are suddenly possible.

Animation also privileges a number of distinct linguistic conventions that can help writers create interesting concepts and explore different directions as the content unfolds. These conventions include the important and subject-specific elements of metamorphosis, condensation, anthropomorphism, fabrication, penetration, symbolism, and the illusion of sound (see box below). Each can be used individually or in combination, as a single occurrence or as a repeating cycle, the variance depending on the project being considered.

Animated language

Metamorphosis—the ability to enact some type of change from one property to another. The versatility of such changes can positively affect scenes, transitions, characters, and stories. For example, changes may be sudden or prolonged. It is entirely possible for one property to become multiple properties, or for one or more aspects of the original form to morph into new aspects but using the original form as a base, or to illustrate particular attributes in morphed form that were somehow hidden in the previous form.

Condensation—involves the economical use of narrative material to suggest or imply information, creating symbolic or metaphorical icons to trigger ideas or possible directions for the audience. Used in conjunction with visual material, this is an effective linguistic tool for exploring characters, scenes, and storylines.

Anthropomorphism—imbues inanimate objects, animals, and settings with human characteristics, giving them the ability to inhabit stories, display their personalities, and, crucially, to interact with each other using human communication attributes. For example, an old chair takes on the characteristics of an old man, his back bent, his joints creaking, and his voice breaking from years of wear.

Fabrication—alternative environments and figures can be constructed to facilitate the idea that a story or event is happening in a believable world.

Penetration—the ability to investigate subjects that are in some way prevented or excluded from being “seen.” This approach is often used in animated projects of a scientific or industrial nature as a way of explaining a particular medical procedure or the way something functions, as it is able to employ stylistic or symbolic interpretations and replicate or change elements to help the viewer understand the principles being explained.

Symbolism—writing for animation demands that creators think about the “visuality” of the form and how narrative motifs can have leading symbolic associations. Use of such visual motifs is important as they help an audience identify with, glean knowledge from, and understand the wider context of characters and situations, thus helping them to comprehend a storyline.

Illusion created by sound—used to support an action or as interludes to accompany more abstract narrative ideas as the production develops, sound acts as a vital ingredient in bringing a complete picture to the audience. Both “diegetic” sounds (dialogue or natural noise created by an action) and “non-diegetic” sounds (soundtrack, effects, and narration) heavily influence an audience’s appreciation of the production.

Approaches to scriptwriting

Unless a specific brief has been set requiring an answer, such as an advertising campaign promoting a particular product or service, the job of the scriptwriter is first to seek inspiration for the story. This can come from a rich variety of sources, including a writer’s own experience, observations, and ideologies, or from responding to facets of the experiences of others. These could include recollections, interpretations, dreams, or fantasies. Such starting points are known as the “premise” or “inciting incident” for a story, acting as a driving motivation for the production as a whole to be made.

In attempting to establish a narrative structure for the story, the scriptwriter must identify important contextual aspects, such as the history, geography, sociology, and duration of the piece. It is vital to introduce immediately a sense of when the story is occurring, where it is set, who is involved, and how long the story lasts, as all these factors directly affect both the following structure of the narrative and the wider context for the audience. Importantly, they also provide an early overview for the writer of the possibilities and limitations of the structure, establish “story laws,” and help define “logic” for the production more broadly. These laws are especially significant in an imagined world that does not conform to realistic conditions since given factors, such as jeopardy, need permission from the scriptwriter to exist. Allowing certain situations to occur, while refusing others, helps embed a conditionally defined logic that the audience can understand and relate to. These conditions serve to signal occasions where, for example, danger might lurk or fortunes could be sought, and have a pivotal role in developing a deep structural narrative because they permit the connected ideas of anticipation, suspense, and release that are crucial to storytelling and which ensure the audience is emotionally invested in the story.

Animation is often used in television advertising as a way of seeing how something works “inside,” penetrating the surface to reveal the inner life of the subject.

Premise

A premise manifests itself as a simple description of an outline for a story in literal form. Through a combination of the scriptwriter’s research, deliberation, and play around the broad subject or focused inciting incident, a collection of words and phrases becomes a more refined description, simply structured into the beginning, middle, and end of a story, which allows the formation of an animated narrative structure to emerge.

In his book Story: Substance, Structure, Style, and the Principles of Screenwriting (1999), Robert McKee suggests that narrative can be identified by some key structural components. For example, a story that explores a coming of age or a rite of passage can be identified as “maturation,” while one that follows the journey of how a central character or characters go from bad to good is classified as “redemption.” A story depicting how a central character, or characters, go from good to bad may be described as “punitive,” while a work that examines the struggle between knowing right from wrong and acting on those impulses can be regarded as “testing.” “Education” describes those stories that explore how characters “learn” to see a new direction, while “disillusionment” represents stories that explore how a character might be turned to having a very negative worldview.

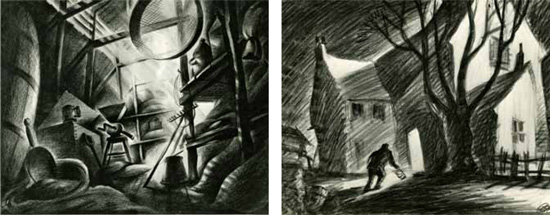

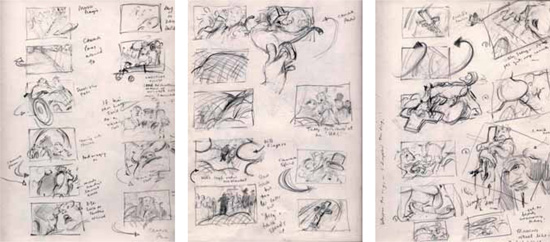

These early drawings for Animal Farm (1954) not only help visualize scenes, but also allow a sense of mood and atmosphere to be evoked that underlines the sentiment of the story.

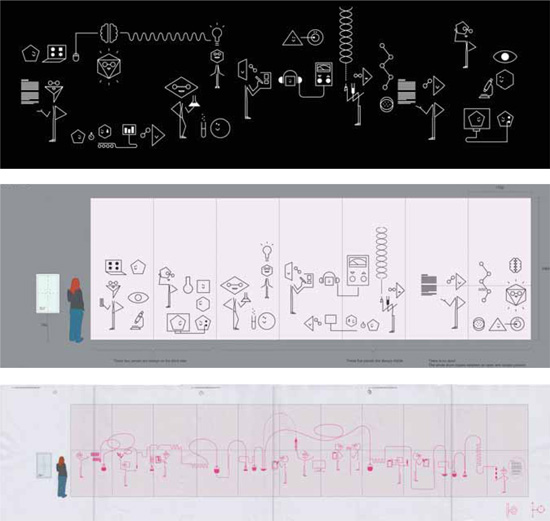

Grant Orchard employs a story frieze to lay out his animated exhibition design for the “Live Science” exhibit in London’s Science Museum.

Story ladders and friezes

There are simple visual and textual mechanisms, such as storyboards (see pages 75–81), to help writers quickly review and test the premise of a story. As animation is a highly visual medium, it makes sense for the writer to get used to seeing his or her ideas in rough visualized preproduction format. For example, a story ladder can be employed to review the main aspects of the plot before subplots or additional storytelling information is considered. Here, single panels are roughly drawn and contain brief written descriptions of plot developments. A story frieze performs much the same purpose, but is often displayed in a horizontal line or grid format.

Once a story has been decided, it then needs to be carefully constructed and tested so that all of the informative events link structurally toward a conclusion. This is known as a “plot.” In animation, the plot is often designed in tandem with the narrative structure, which is known as a “storyline” or “story arc.” Storylines allow the textual depiction of several characters involved in the story to be accommodated in parallel with plot events, while story arcs usually describe extended or ongoing storytelling in animated television series that may run over several episodes. Both storylines and story arcs offer a framework that supports the continuity and accuracy of the story, the latter helping the audience understand where the story was left and where it picks up in a subsequent episode as part of a bigger series of programs.

A plot is generally made up of a simple structure involving some or all aspects of exposition, rising action, conflict, climax, falling action, and resolution. The beginning of a plot opens with an exposition that introduces the key characters and settings necessary to tell the story for an audience. The plot develops through a rising action in which events occur that help the audience understand both the passing of time and the way in which the events are interlinked together. These events inevitably precede some kind of conflict, where problems between a character and other characters, environments, society at large, or even with themselves, are illustrated and amplified for the audience. This leads to a climax where these agitating factors combine to “peak,” perhaps exposing secrets or signaling struggles and conflicts, before receding through the falling action where the impact of the climax is reflected through characters or situations. A resolution can be achieved when a conclusion to the plot is attained, although some plots deliberately prevent this in order to keep a story open or alive. Resolutions allow an audience to release their tension or anxiety, whereas a non-resolution deliberately keeps an audience in a state of suspense.

British animator Joanna Quinn begins to outline a plot, using quick sketches to capture her ideas for framing scenes and also thinking about how to animate the unfolding story through transitions and camera moves.

Writers might consider using the following plot themes as useful starting points for creating their own animated material, or categorizing the work of others. Here are some examples of animated productions, or productions that use animated special effects, that illustrate the themes described:

Adventure—Alice in Wonderland

Ascension—Mulan

Descension—Avatar

Discovery—Magnetic Movie

Escape—Chicken Run

Excess—101 Dalmatians

Forbidden love—The Hunchback of Notre Dame

Love—Beauty and the Beast

Maturation—The Jungle Book

Metamorphosis—While Darwin Sleeps

Pursuit—Beep, Beep (Wile E. Coyote and Road Runner)

Quest—Jason and the Argonauts

Rescue—Belleville Rendez-Vous

Revenge—Coraline

Rivalry—Prince of Egypt

Riddle—2001: A Space Odyssey

Sacrifice—The Lion King

Transformation—Toy Story

Temptation—Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs

Underdog—Cinderella

Adapted from Lewis Carroll’s book of the same name, Alice in Wonderland (2010), directed by Tim Burton, is a lavish adaptation of this childhood adventure, complete with resplendent sets, unworldly characters, and a magical score composed by Burton’s long-time collaborator, Danny Elfman. © Disney

Genre in animation

We are used to going to see “action,” “horror,” or “romantic comedy” movies at the theater. These are examples of “genres,” which embody typical codes and conditions of a particular narrative structure that allow such a story to be told. For example, a film classed as belonging to a “science fiction” genre has visually “coded” objects, environments, and plots that help an audience identify key components and make vital associations. In this example, coded clues such as hostile aliens, weapons, and spacecraft, or environmental or motivational conditions such as travelers venturing into space or saving our world from calamity, are all established markers of the genre.

Scriptwriters often make use of an audience’s pre-existing knowledge of genres, and many animated feature films pay homage to film history through certain scene enactments, or by parodying visual gags and jokes. Many of the films from Aardman Animations rely heavily on such structural traits from well-known live-action films. An example is Chicken Run (2000), which heavily borrows scenes, situations, and even visual escape devices from The Great Escape (1963).

On a wider level it should be noted that some film critics have mistakenly categorized animation simply as a genre of film because of its strong association with children’s cartoons. Animation is a form in its own right that supports its own framework of genres that are being developed and redefined continually. They fall into seven distinct categories, known as “deep structures,” including Abstract, Deconstructive, Formal, Political, Paradigmatic, Primal, and Re-narration.

Categories of animated genres

Abstract—includes animated productions where a non-linear or nonobjective approach is adopted for subjects or themes, often connected with expressionistic attempts by the creator to explore outside traditional storytelling conventions. Works are often biased toward investigating the form of animation rather than using text as a foundation. The work of Norman McLaren neatly fits the abstract genre of animation.

Deconstructive—productions fitting this description involve displaying the reasons and methods of their construction for comic or critical effect. Animated cartoon works often fit this category as they openly portray narrative and visual methods derived from cartoon conventions of interpreting representational drawing.

Formal—works included in this category display a linear set of conditions and values that are consistent, enabling representative interpretations of a particular world to be imagined.

Political—these animated productions have the facility to incite and empower through the communication of a moral or ideological political agenda, expressed through a core or combined narrative and/or aesthetic direction.

Paradigmatic—animated productions that use pre-existing visual or literary sources as a foundation, such as adaptations of literary classics, children’s stories, or graphic novels. Such productions are often governed by rules that remain consistent throughout episodes and series.

Primal—includes animated features that explore such states as consciousness, dreams, and the “unknown.”

Re-narration—works that in some way reinterpret an established story or chapter of events from a different perspective, giving them a different viewpoint and possibly altering the emphasis placed on key moments.

Guilherme Marcondes’s stop-motion film Tyger (2006) actively involves puppeteers in the frame as a way of emphasizing the construction of the film.

Script development

Scriptwriters must balance the educational, informative, or entertainment demands of the premise of a story against the need to strike the right tone with the target audience. Using key principles and characteristics of the animated form is crucial to delivering this through the lifetime of the story, ensuring that the writing allows for the mixing of visuals, sounds, and motion to create the necessary desired dramatic, stylistic, and structural effects that convince the viewer. To do this effectively, a series of steps is taken by the scriptwriter as he or she attempts to build the framework for a story from the original inciting incident. These steps include a prose brief, a step outline, event analysis, and synopsis of the story.

Prose brief

With the beginning, the middle, and the end of the story agreed and written in note form, a “prose brief” can be established. This develops ideas for thematic topics to be covered in particular scenes and suggests where these ideas might occur in the overall telling of the story. A prose brief textually outlines key components of the story and provides a foundation for the writing team to build other related layers of narrative, decide where and how they want characters to be introduced, establish the viewpoint the story is written from, and so on.

Step outline

This is a useful device that breaks down a story factually into detailed chronologically numbered scenes. Each scene has a descriptive commentary that explains the main action that will occur and provides clear instruction about what effect this action has both on subsequent scenes and on the story at large. The outline is created by the scriptwriter or writing team and acts as an important guide for the preproduction team to signal and understand key actions in the story.

Event analysis

Using the step outline as an overall guide, the production of an event analysis provides a comprehensive checklist for the script supervisor or editor to spot gaps or inaccuracies in the script. The event analysis matches essential movements of action against specific plot developments and characters. This analysis in turn highlights pivotal movements of individual characters through the development of the narrative, signifying the desired outcomes and emotional responses required or expected from the audience.

The script supervisor or editor first checks the event analysis to ensure that a scene’s details—including locations, characters, and action—are adequately described and, if necessary, that they are consistent with other episodes in the series. Consideration is then given to how the scene helps develop the plot as part of the overall story. The script supervisor or editor looks for evidence that demonstrates how the central characters develop their involvement with the plot, creating the desired emotional feeling, and providing sufficient information for the audience to understand how the events contribute to their comprehension of the main storyline. At this point, the script supervisor should signal any inaccuracies, including stylistic deviations or descriptive omissions. He or she should also be mindful of suggesting ways to simplify the story if ideas are too complicated, or if they do not utilize the animation production possibilities open to the writer. For example, rather than writing overly descriptive dialogue, it is often easier for an audience to understand symbolic or metaphorical visual devices coupled with shorter narratives, as these resonate more immediately with a viewer.

Grant Orchard’s animated shorts for LoveSport premise actions around simple story events that trigger resulting actions, using simple visual and aural motifs with carefully chosen and customrecorded sound effects.

Synopsis

Written as an overview of the story, a synopsis aims to establish all of the necessary information about the intended production from a more distanced and objective perspective. In essence, it is written to provide clarity for the preproduction team, but is also useful in either attracting or reassuring creative partners or investors. The synopsis usually introduces the location or environment for the story, summarizes the plot, includes information concerning the central characters and their connection to each other, and illustrates the key events that help develop the story toward a conclusion for the audience. A typical synopsis is normally between six and eight paragraphs long.

Treatment

With the premise of the story set, the prose brief, story outline, event analysis, and synopsis completed and agreed, a “treatment” can be finally constructed. This will detail the story’s theme, plot, structure, and characters in a complete textual and possibly visual form. By this stage, the story will have been scrutinized several times by the script development team, editor, and writer(s) and will have undergone structural, thematic, and stylistic changes that better support the telling of the narrative. The treatment will explain the reasons behind the story and how it will unfold dramatically for an audience, and it will also incorporate elements such as key moments of action where the plot changes direction and pace. It is likely that the treatment will also have elements of sample dialogue to provide a feel for how the story will be told.

Analyzing a script

The finished script now holds core information about the project and needs to be checked and cross-referenced. It contains details of the storyline or story arc, settings and environments, scenes, characters, dialogue, sound effects, and points of action that will be visually rich, as descriptions will be written in such a way as to provide instructions for key details of the production to be interpreted by the preproduction team. This core information directly affects the next stage of the preproduction process for designers, animators, and voice-over artists. It is the director’s responsibility to ensure that meetings are conducted to read through the script, highlighting key areas that different crew members in the preproduction and production process need to take account of and prepare for. These might include specific technical requirements for the set to be able to adapt to scenic changes, or where emphasis will need to be placed when recording dialogue.

An important aspect that requires checking, regardless of the type of animated production, is running time. If a script has been written for a commercial, it must be aligned with the air time the commercial is to occupy. Similarly, an episode of a television documentary will have stipulations from the commissioners of the project regarding the running time of the piece. Inevitably, this means that the script must allow suitable “lead-in” time to the content and sufficient space to reflect on the material at the conclusion of the production.

Conclusion

With a script complete, the process can begin of originating visual material around the story and collecting the necessary research material (see pages 55–71) to support the delivery of the story or idea to an audience. The director also begins to look for voice-over actors who can convincingly carry off their interpretations of the dialogue required to help bring the animated production to life. In addition, the director must consider who to approach and brief to provide a musical score, act on discussions with members of the crew relating to sound and lighting effects, and approach special-effects studios as necessary (see pages 106–25).