Sharing the Stars With Your Guests

That is the exploration that awaits you! Not mapping stars and studying nebula, however, charting the unknown possibilities of existence.

—Leonard Nimoy (actor)

The oldest stories ever told are those of the stars. We ceaselessly witnessed them throughout our tenure on planet Earth. Without fail, the stars made their grand entrance from the east, rising to the night sky’s zenith, then plunged into the western horizon. While they were aloft, we ruminated about their meaning and created our own. The quest of the astrotourist is both the exploration of the night sky and how the night sky has shaped the history of humanity.

A good place to begin is educating your guest on twilight and its three phases, civil, nautical, and astronomical twilight.

Figure 12.1 Golden Hour/Twilight Distinctions

Source: Image by Author

When the sun’s geometric center is 6 degrees below the horizon marks the threshold of civil twilight. In the morning, it begins at 6 degrees below and ends when the sun crests the horizon. In the evening, it starts at sunset and ends at 6 degrees beneath the horizon. Absent of fog or other atmospheric impediments, the brightest stars and planets can be seen as well as objects on the horizon or around you. Artificial lighting is unnecessary.

Nautical Twilight

When the sun’s geometric center is 12 degrees below the horizon marks the threshold of nautical twilight. The term originates with sailors still able to take reliable readings via prominent stars as the horizon is still visible even without the moon’s illumination. The outline of a terrestrial object will be discernable, with no atmospheric restrictions, but one’s detailed outdoor activities have limits without the use of artificial illumination.

Astronomical Twilight

When the sun’s geometric center is 18 degrees below the horizon marks the threshold of astronomical twilight. At this point, most casual observers would regard the night a wholly dark and particularly in an urban or suburban setting where light pollution is prevalent. The horizon is not discernable, and fainter stars and planets are visible with the naked eye. For a completely dark sky, the sun needs to be more than 18 degrees below the horizon to allow for the observation of galaxies, nebula, and other deep space objects.

Identifying one’s first constellation provokes the kind of exuberance we see in children who learn their first words; a new world opens up. It is a first step toward acquiring their “space legs” to navigate the celestial firmament that dutifully appears every evening. We have always looked to the stars to see what they portend and conceived adages as, “It is in the stars,” “star-crossed lovers,” or “my lucky star,” or want to know if one’s “star is rising.” The first star-sign astrology column began in 1930 and has captivated the attention of millions of readers across our planet.1 Astrotourists look for meaning in the tapestry of the night sky because it connects them to the universe. How is it possible to resist experiencing a convergence with the cosmic when infinity is spinning overhead? The stars have been a source of inspiration throughout time, and though much of it has been lost due to our urban lifestyles, it is being reawakened through astrotourism.

With the stars as a constant, we learned to navigate land and sea, giving us the means to spread our species. By studying the stars, the ancients knew how to foretell the seasons, animal movements, and civilizations sprung up. For some cultures, the stars informed them when the rains would come when it was time to shear the sheep, and in the case of Australia’s aboriginals when it was time to collect the emu eggs.

Cultures throughout time, bound by their relationship to the night sky, created their own unique stories. We experience the rotation of the earth, as the stars crest over the horizon, as it spins at speeds that would belie the gentle ride we experience. The earth’s surface at the equator moves at a speed of 460 meters per second—or roughly 1,000 miles per hour.2 As the constellations emerge from the darkness of the horizon, they bring with them the legends and myths that have endured throughout the ages.

In the early 1920s, the International Astronomical Union (IAU) decided upon 88 constellations officially recognized by all astronomers. The breakdown consists of 17 human or mythological characters, 29 inanimate objects, and 42 animals. Stories about the constellations are told worldwide, in a myriad of languages and by many cultures. The Greco-Roman astronomer Ptolemy named 48 of the 88 constellations we know today, with many already considered constellations by his forebears, like Leo the Lion. This constellation was one of the earliest names, and in one Leo myth, the lion and Hercules do battle. The marauding Nemean lion terrorized the countryside yet had a hide so tough it could not be harmed by any weapon known to man, leaving our hero to fight the beast with his bare hands.

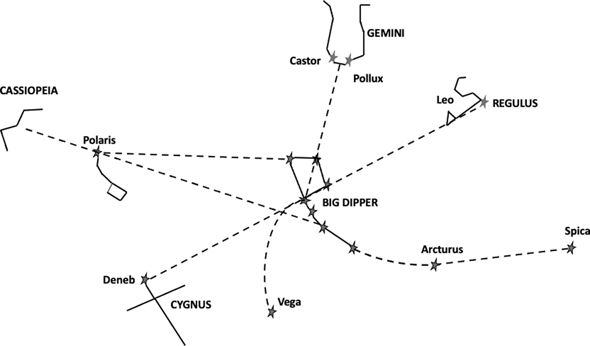

No matter where your travels take you or accommodate the astrotourist, the constellations are overheard with a completely different palette of stars in the southern hemisphere. The northern array was full of narratives from ancient civilizations, with some dating back 6,000 years ago. Historians have concluded that the Greek constellations originated in the Mesopotamian civilizations of the ancient Babylonians and Sumerians. Their stories, legends, and myths are full of monsters, heroes, villains, treachery, comedy, tragedy, and drama. To remember these nighttime narratives, constellations and asterisms became illustrations and mnemonics of the sky. An example is using the Big Dipper to locate other constellations in the sky and the prominent stars within each.

Figure 12.2 The Big Dipper as a Pointer

Source: Image created by Author

Story telling predated the written word and was shared to educate, entertain, instill values and morals, and preserve cultural identities. Stories are universal as they can bridge cultural, linguistic, and age-related divides. Stories are effective educational tools because listeners become engaged and therefore remember. Storytelling can be seen as a foundation for learning and teaching.3

Astrotourism is a global attraction and not based on a specific cultural underpinning. To see Angkor Wat, one has to travel to Cambodia and explore Amsterdam’s canals; one has to travel to the Netherlands. Traveling to a country is to experience their social and ethnic identities, and it is expressed through their folklore, art, architecture, and food. These accomplishments are an outgrowth of the country’s people, essence, and identity, but the stars’ stories predate modern civilizations by the millennium. Long before civilizations grew to become the countries we know today, people told stories about stars laid down by the ancients.

From 1989 to 2018, my company toured a theatrical production created to raise awareness of our night sky’s loss due to light pollution. There was an engagement in Rome, and upon entering the theater, the question was posed, “How old?” The house manager responded, “900.” Startled by the response, “This place is 900 years old!?” He answered, “No, it was built in 900.” “900 AD! This place is ancient!” To which the curator said, “No, in Rome, that is just old.”

Even in a city that can easily trace its history back 2,500 years, it is still a blink-of-an-eye on the clock representing our time on earth. Human’s connection with the stars began before language, writing, architecture, or pottery shards. Western civilization perpetuated the star myths of ancient Greece and those narratives are the ones we are most familiar with. They are far from the whole picture; like the night sky, we will never see all of it at once and the range is stellar.

The Lummi Tribe of the Pacific Northwest tells how Coyote liked to take out his eyeballs and juggle them to impress the girls. One day, while juggling, he threw one so high it stuck in the sky and became the star, Aldebaran. In Hawai’i, the demi-god Maui used his “Manaiakalani,” a magical fish hook (the tail of Scorpio) and with it caught the ocean floor. He thought he had an enormous fish on the line and reeled up the bottom of the ocean to the surface. His catch became the mountains of the new islands, resulting in the birth of Polynesia.

Though Western civilization’s constellations in the Northern Hemisphere were named after Greek myths, the planets were named after Roman gods, and Arabic cultures named the stars. For Western astronomy, most of the accepted star names are Arabic, a few are Greek, and some are of unknown origin. Typically, only bright stars have names.4 Many of the prominent stars known today are of Arabic origin as they bear names given to them during the golden age of Islamic astronomy (9th–13th centuries). The majority of stars’ names are related to their constellation, for example, the star Deneb means “tail” and labels that part of Cygnus the Swan. Others describe the star itself, such as Sirius, which translates literally as “scorching,” aptly named as it is the brightest star in the sky. Many prominent stars bear Arabic names, in which “al” corresponds to the article “the” and often appears in front, for example, Algol, “The Ghoul” (10th century).5

The intent here is to ignite the reader’s enthusiasm and imagination and gird them to familiarize themselves with the many tales of the night sky as it will become the content for your guest’s evenings under the stars. They have enthralled people for thousands of years and will stimulate the curiosity and entertain today’s astrotourist. There are numerous books on the subject, with some listed in the Resources.

The following story shows how various cultures over millennia used one star. Alpha Ceti is the Bayer classification for a star in the Southern Hemisphere. The Bayer classification was created by the astronomer Johann Bayer in 1603, who circulated a system identifying all the stars visible to the naked eye.6 More than a thousand years before Johann named it, it was called Menkar, or in Arabic, Al-Minkhar meaning “nostril,” and it is the part of the constellation Cetus, the sea monster. Perseus had to slay the monster to save Andromeda (also the name of a galaxy) and the other chief characters in the Perseus legend, Cepheus, Cassiopeia as well Andromeda, Cetus, and Perseus, all have their place in the night sky as constellations.7 The term cetacean derives from Cetus, which in Latin literally means, “huge fish.”

Three and half centuries later, the Star Trek franchise made reference to the same star Bayer name, in a 1967 episode “Space Seed,” and in the 1987 movie “Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan” but reversed Bayer’s designation to “Ceti Alpha V.” The reason this is mentioned is that it was one of the most iconic episodes in people’s memory of the Star Trek franchise and demonstrates the durability of star lore.

Given that most people, especially the adventure traveler and outdoor enthusiast, love whales and dolphins (there is constellation Delphinus, the Dolphin), they will be delighted to learn this interesting anecdote. Interestingly, Greek mythology gods did not place themselves into the night skies but were responsible for placing mortals into the heavens to memorialize their deeds, their treachery, heroism, and impart upon the generations to follow what it meant to live a stellar life. The references to the stars are with us still and will always continue to be written into our own stories and legends.

Millennials are fast becoming increasingly sophisticated travelers, less destination-oriented and more (authentic) experience-oriented. From Antarctica to remote parts of Newfoundland, it is the unique experience tourists seek and are sharing through social media. The search for eclectic adventures takes travelers of all ages to winter locations, no longer put off by the cold or even a barren winter landscape.8 A pristine nightscape, replete with the constellation’s mythological stories, makes their entrance from the east and their exit to the west. It is a unique and wondrous adventure that appeals to both today’s and tomorrow’s adventure traveler.

Australia has vast stretches of “Outback” that makes up about 6 million acres, bigger than several European countries.9 Australian Aboriginals can claim to be the oldest continuous living culture on the planet. Recent dating of the earliest known archaeological sites on the Australian continent—using thermo-luminescence and other modern dating techniques—have pushed back the date for aboriginal presence in Australia to at least 40,000 years. Some of the evidence points to dates over 60,000 years old.10 As old as the stories are about the constellations laid down by ancient Greece, compared to Australia’s aboriginal culture, they are embryonic in comparison. In Australia, one of the best-known Aboriginal constellations is the Emu. It is an exquisite spectacle that is more convincing and apparent than European constellations. In Ku-Ring-Gai Chase National Park is a rock engraving of an emu, and when the Emu in the Sky stands above her portrait, in the correct orientation, it is when real-life emus are laying their eggs.11

While most people easily identify Orion’s belt, their knowledge of who he was or how he got into the night sky is a mystery waiting to be revealed. This is just a single tale from one civilization at one point in time in the planet’s history. There are many legends and myths from various dormant cultures waiting to be shared again. As the tales of the stars come to life, they will give the astrotourist a rich, informative, memorable, and insightful experience as they learn about the constellations. They yearn for the relatable and subjects that broaden their horizon. Just as the “star-tales” of ancient Greece were a popular form of make-believe, our broad-based love of science fiction/fantasy is a way to connect travelers with the night sky overhead and spark their musings with what once was and what could still be.

The well-known constellations, begun by the Sumerians and adopted by the Greeks, was limited by what could be seen in the Northern Hemisphere. It was not until the 16th century, almost two thousand years later, when European explorers traveled south of the equator and were exposed to a categorically different night. For one, the constant of a North Star was gone; it would have been a wonderment for the sailors to see a night sky so contrary and polar to anything they knew, not unlike the first time astrotourist today. These new sightings and findings were grouped into new sets of constellations named after the new species they encountered, like Pavo the Peacock.

Figure 12.3 Emu in the sky (photo credit Barnaby Norris)

Here, a moment is taken to set some history straight. Johannes Bayer was accredited to the 12 new constellations included in his publication Uranometria in 16036. However, he made the star charts based upon the sailors’ discovery and navigators who made the journey years earlier. The First Dutch Expedition to Nusantara (Indonesia) was a sailing trip from 1595 to 1597. The navigator Peter Dirkszoon Keyser and some colleagues on the first Dutch trading expedition to the East Indies, known as the Eerste Schip Vaart12 (First Shipping). The observations made on the Eerste Schip Vaart had gone directly to the Dutch cartographer Petrus Plancius in Amsterdam. These stars, divided into the 12 new southern constellations, first appeared on a globe produced jointly by him and Jodocus Hondius in 1598. Hondius published revised versions of this globe in 1600 and 1601.13 The Dutch historian Elly Dekker has demonstrated that Bayer almost certainly copied the southern stars’ positions from these Hondius globes, as he had no original observations to work from.12

Between 1751 and 1754, the French astronomer Nicolas-Louis de Lacaille was stationed at the Cape of Good Hope and cataloged the positions of 9,766 southern stars in just 11 months. Unlike many of the larger, brighter constellations, which were chiefly based on mythology and legend, Lacaille chose to fill uncharted areas of the southern sky with new constellations representing inanimate objects—apparently a personal resolution he made to honor artisans by their tools and inventions. He is considered “the Columbus of the starry southern skies.”14

From the perspective of European astronomers and explorers, who put their stamp on the Southern Hemisphere’s night sky by naming groupings of stars into constellations, there were no legends or myths associated with them. Perhaps, because at this point civilization was living in the “Age of Reason” that began with Descartes and Newton, there was no space in space for fanciful myths and extraordinary stories to entertain and educate. “It looks like somebody’s attic!” was how Heber D. Curtis, director of the Allegheny Observatory, described Lacaille’s chart of constellations. Consider leaving it to your guests to fill in the back story of how the Pendulum Clock, the Artist’s Easel, or the Sculptor’s Chisel found their way into the night sky.

There is an endless number of night tales as told by the Navajo, Shoshone, Pueblo, Hopi, Zuni, Apache, Zulu, Tswana, Xhosa, Bedouin, Maoris, Innuit, Incans, Mayan, Aztecs, Chinese, Hindu, and the Bushman. Every place an astrotourist travels to, there is a lore to be re-told anew and will be illustrated by the stars that sweep overhead every evening.