Chapter 2. How the Web Medium Has Evolved from Its Oral and Print Origins

On Media Determinism

Imagine if the only way to learn anything was to memorize an entire story based on a series of tone poems. Prior to literacy, that is how all knowledge was transmitted from one person to another. Consider the Homeric epic poems. The whole of the Iliad and the Odyssey are written like a series of tone poems to be sung. And that is how they were relayed for centuries before they were finally written down. With no text to rely on, there is no way one can remember what occupies thousands of pages of writing without the poetic structure of the stories (mnemonics). Lacking text, preliterate cultures developed elaborate mnemonic devices and embedded them into their storytelling. Because these mnemonic devices occupied so much of their minds, they did not have space for other kinds of thinking. The study of how the medium (such as oral, print, or Web) that you use affects what you can and can’t think about or communicate is called media determinism.1

1 Marshall McLuhan is famous for saying, “The medium is the message” (or massage). Roughly, what he means is that the medium one uses to communicate determines what one can communicate. McLuhan and his student Walter Ong pioneered a kind of language analysis that powerfully explains how human language works differently depending on the medium. McLuhan and Ong focused on the distinctive qualities of literate cultures to understand how literacy changes the way we think and communicate. They used sophisticated cultural and historical analysis to demonstrate that when a culture becomes literate, the nature of its stories changes.

Media determinism is the primary lens that we use in this book to study the differences between writing for print and writing for the Web. Most of this lens was developed by Marshall McLuhan and Walter Ong to study how human thinking evolved as our cultures evolved from oral to print. We extend this lens to look at how human thinking is changing as we move from print culture to Web culture. But before we talk about the evolution from print to Web, it is useful to consider the evolution from oral to print, if for no other reason than to engage the skeptical reader in examples of how the medium we use affects our thinking. When the reader is ready to accept the lens of media determinism, we can use this lens to view the transformation from print to Web.

There are countless ways in which a literate culture differs from a preliterate one. One very important difference is in the way the human brain works. If there is no longer a need to remember all the names and places and things people have done because they are written down, the mind is free to think in different ways. One important facet of literate culture is abstract thought. Instead of particular people, places and things, humans are free to think about kinds of people, places and things, and to develop classification systems and every manner of logic relating kinds of things. Philosophy, science, and mathematics require the signs and symbols of the written word. If you’ve ever tried to work out a complex math problem in your head, you understand the importance of symbols in the development of human thought.

It is tempting to see the transition from oral cultures to literate cultures as a matter of absolutes, as though one moment people thought in oral ways and the next moment they thought in literate ways. In fact, the transition is much more gradual. Literacy is not easily acquired by a culture. In western cultures, the transition from an oral culture to a literate one took place over thousands of years. Even in the twenty-first century, remnants of orality persist in a primarily literate culture. The popularity of lyricists such as Bob Dylan speaks to remnants of how humans’ brains were once wired, if nothing else, to augment our primarily literate understanding. Even today, print doesn’t supplant oral traditions; it augments them. With multiple choices of how to communicate, we can tailor our medium to fit the circumstance.

As our print culture becomes ever more a Web culture, we need to look at the differences between print and Web communication with a similar lens, just as we view the transition from oral culture to print culture. The similarities are striking.

• The move from oral to print was gradual, as is the move from print to Web. Web publishing has not replaced, and will not replace, the need for print. It merely augments print and provides a means for quicker information retrieval, among other things.

• The move from oral to print changed the way humans think, as does the move from print to Web. Consider the change in our thinking as we consume ever more numerous, smaller bits of information, made possible by Web applications such as Twitter.

• The move from oral to print had wide-reaching socio-economic implications, as does the move from print to Web. The printing press brought literacy to the masses for a narrow band of learning; the Web brings literacy to the masses for a much broader scope of human knowledge.

Showing these and other facets of the evolution of human media is a project for a whole academic discipline—not for this book. Our intent is not to delve too deeply into this discipline. But neither can we ignore its insights. What we provide instead is a small corner of the vast literature on the subject, one which is particularly illuminating in showing how media evolution affects the way we think and write.

Along the way, we will develop a view of Web writing effectiveness that isn’t just a how-to book on writing, but that helps you understand why our approach works.

Spaces between Words

The change from oral to literate culture in western societies was gradual, but not uniform. Some moments in this history created great earthquakes of change in human thought, and others, mere tremors. Of all the milestones in the transition from oral to print, one event in western history perhaps best helps us understand media distinctions and transitions: the invention of spaces between words. Other events were important, of course, but we focus on this one because it contains many of the features that we want to highlight in the move from print to Web.

Prior to the Scholastic period (beginning in the twelfth century A.D.), most texts contained no spaces between words. It is hard for modern literate people to understand what reading was like before there were spaces between words. Imagine looking at a line in which all the words flow together, and consider how difficult it was to read line after line of text printed in script. The only way to make sense of it was to read it aloud; if you tried to read it silently, you frequently made mistakes in slicing up lines of text into discrete words (see the sidebar explaining how the eyes cue into spaces between words to read text).

Because pre-Scholastic texts were read aloud, writers used the same mnemonic techniques that oral cultures use for their mythologies—meter, rhythm, and so forth. The primary value for the written word in those days was the lack of a need to remember Iliad–length oral passages. But the reader still needed to remember passages as long as a page in length before actually grasping the sense of the text. Consequently, readers’ thought patterns still had an oral character to them.

It was monks in the scriptorium who started inserting spaces between words. They did this for copying. It was a lot easier to copy text with spaces than without. The practice began in the ninth century in Ireland and spread across Europe over the next three centuries. Not until the twelfth century did the practice of uniform spacing become the standard across Europe. Though originally devised to ease copying, it soon had widespread effects on the way people read and understood content, and on how writers tailored their manuscripts for the reader.

Paul Saenger (1997) wrote the definitive work exploring the effects of spaces between words in the context of how the medium changed the message. He noted that

Whereas the ancient reader had relied on aural memory to retain an ambiguous series of sounds as a preliminary stage to extracting meaning, the scholastic reader swiftly converted signs to words, and groups of words to meaning, after which both the specific words and their order might quickly be forgotten. Memory in reading was primarily employed to retain the general sense of the clause, the sentence and the paragraph. Albertus Magnus, Thomas Aquinas, Roger Bacon, Duns Scotus, and William of Ockham, despite their divergent national origins, all wrote similar scholastic Latin remarkable for its clarity and precision of expression, which was achieved at the sacrifice of classical rhythm, meter, and mellifluous sonority. (Saenger 1997, 254–5)

The effects of using spaces between words were far reaching. By the thirteenth century, literacy and original writing blossomed, even before the printing press. Writing soon became a medium that enabled all kinds of expression not seen since the Greeks, such as grammar, logic, theoretical mathematics, and science (Saenger 1997, 202–5).

One important effect was the notion that it was now the scribe’s responsibility to make the text readable for the audience. Before then, literacy was an elitist activity that took years of leisure to acquire. It was a mark of this learning, and of breeding, if one could read text inscriptura continua (without spaces). It was therefore not the responsibility of the scribe to make the text clear; the scribe wrote as he or she deemed fit. If readers managed to decipher the text, they were worthy of its contents. As more and more writing became accessible, readers began demanding clarity, and writers who did not write with the reader in mind fell out of favor and out of our literary histories.

Another effect of using spaces between words related to the way libraries were set up. Prior to silent reading, libraries were constructed with carrels that kept the muttering of the scribe to a dull roar. Book and scroll retrieval were the purview of the librarian. And indexes at the back of books were nonexistent. But the construction of Scholastic libraries is much like the libraries of today, with open collections and central tables where readers can sit side by side without disturbing each other. Most books in these libraries contained back-of-the-book indexes. These libraries also included the first catalogues, “with alphabetical author indexes and special union catalogues representing the holdings of libraries in a city or region” (Saenger 1997, 263). For the first time, literacy included not just being able to decipher an individual text, but understanding the text in the context of a genre or collection. It is no surprise that the first modern universities were founded during the Scholastic period.

The invention of spaces between words was only one point in a string of developments that contributed to the maturing of the print medium. Because clarity became a value of writing with spaces, spaces between words opened literacy for the masses to understand. This ultimately ushered in the Renaissance (Eisenstein 1983). But the Renaissance was only truly made possible by the invention of the printing press. Parchment and vellum were expensive. Copyists were limited mostly to monasteries, and to private publishers, who charged a king’s ransom for a book. There was no practical way to get books to the masses until the printing press and the complementary Chinese invention of paper—which was as cheap as papyrus and as durable as parchment. Libraries rapidly expanded their collections. Publishers could produce books in enough quantity to drive the price per book down to a level affordable to the expanding merchant middle class. And institutions of higher learning began springing up everywhere, where middle class youth could gain their letters. These universities became the centers of new knowledge, organized by discipline—much as today’s universities are.

We won’t delve into all the effects of the printing press. Consult McLuhan and Eisenstein if you’re interested in those topics. But we do want to highlight how the printing press, together with such inventions as spaces between words, changed the reader/writer relationship. Prior to print becoming a mass medium, the practice of audience analysis was a lost ancient art (specifically, Aristotelian art). Scholastic readers had quite similar learning backgrounds in the scriptorium. The production of secular books was confined to the trades, which likewise had clear learning curricula. All learning was conducted in Latin, which was universally understood in Europe among learned people. So writing for the medieval reader did not require much audience analysis. One wrote on topics of interest, free from worrying about the reader, aside from conventional notions of clarity and grammar, which were relatively new at that time.

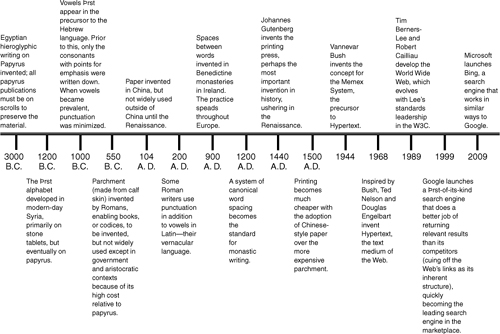

As print has evolved since medieval times, audience analysis has ebbed and flowed with the changing reader/writer relationship. Print became ever more a mass medium, spanning languages and cultures, incorporating many purposes outside of the practical sciences (such as literature), and branching out into other forms, such as newspapers and magazines. And effective writing evolved with it (Figure 2.2).

Figure 2.2. A timeline of media determinism.

Outside of literary art, writing for print as we encounter it today is first and foremost about understanding the discrete audience for which the publication is produced, and writing for that audience. Of course, you never really know your audience, which is a convenient fiction (Ong 1984, 177). But the fiction is based on facts or stereotypes about the readers of the publication. So writing for print must start with at least trying to understand your audience, and either addressing your writing to their known attitudes or invoking the audience to follow your prescribed path through a topic in the absence of such knowledge. Except in specialized circumstances, you really know very little about your actual print audience. That’s why writing for print often concerns itself with expressing interesting things in interesting ways and hoping your audience connects with it.

The point of this brief history of the print medium is to convince you that our communication is often affected by the medium we use. Some of the changes in the print medium—such as the invention of spaces between words—began as conveniences to save time or resources. But they had profound unintended effects on the way the print medium was used to communicate thereafter. These changed not only the practice of writing, but also the topics that writers explored, and the very way readers thought about those topics. The rest of this chapter, and the rest of the book, will delve into similar evolutions in the Web medium, which were perhaps developed as conveniences, but which are beginning to have profound effects on our communication, and on the topics we are able to communicate. In particular, how we write relevant content for a Web audience is as revolutionary as how writers needed to write for a print audience after the invention of spaces between words.

The Limits of Print Media and the Origins of the Web

Though print literacy opened the mind to new ways of thinking, it too is limited. Walk into a library and you will soon be overwhelmed by the amount of knowledge contained on its shelves. There is only enough time to consume a tiny portion of that knowledge. As the centuries of scholarship have advanced since the Scholastic period, the scope of what one can master has continuously shrunk. By the middle of the twentieth century, the advancement of new knowledge had become so specialized that people within related fields often couldn’t communicate effectively with one another.

In this environment, writing also became a relatively specialized task. Outside of the mass media, each periodical had a well-understood audience and purpose. An aspiring writer for one of these periodicals simply needed to read it long enough to understand the gaps in research and fill those gaps with prose that fit that periodical’s guidelines. Audience analysis was also relatively easy—the readers were the other authors who frequently published in the journal. If you had read an academic periodical long enough, you could form a good understanding of the audience based on the writers who published in it. But if you attempted to publish in a journal for a related field, you might have more trouble succeeding. It was as though each specialized journal had its own way of communicating in print. This stifled innovation, which needed good communication between practitioners in related fields.

In 1945, a visionary MIT professor named Vannevar Bush published an influential article in the Atlantic Monthly—“As We May Think” (1945)—proposing a way for science to transcend the limitations of print. Bush saw clearly the need for a radical new information system that could give researchers access to the work of colleagues in a fraction of the time and space required by the antiquated print journal. “There is a growing mountain of research,” Bush wrote. “But there is increased evidence that we are being bogged down as specialization extends. The investigator is staggered by the findings and conclusions of thousands of other workers—conclusions which he cannot find time to grasp, much less to remember, as they appear” (Bush 1945, 1–2). However, Bush’s proposed Memex system relied on antiquated technology, which had various limitations of time and space.2 So his vision was never realized in his lifetime. (He died in 1974.)

2 One such antiquated technology Bush refers to is stenotype, which provides a written record of speech. But speech is not an expressive medium for such things as conceptual, mathematical, or scientific findings, as McLuhan, Ong, and others pointed out repeatedly in the decades after Bush.

It was not until computers became reliable and economical tools with which to store and communicate information that hypertext was born. Ted Nelson and Douglas Engelbart credit Bush’s essay with the genesis of the idea for hypertext. And it wasn’t until various hypertext collections were connected by the Internet that the basic concepts of the Memex system began to take shape in the form of the World Wide Web.

The Web was developed by Tim Berners-Lee and Robert Cailliau in 1989 for a group of physicists associated with CERN in Geneva, Switzerland (Berners-Lee and Fischetti 1999). The idea was quite simple: provide a way to publish hypertext over the Internet collaboratively. The original purpose of the Web was to link communities of physicists in order to publish their work more quickly and efficiently than the static print journals could do. Berners-Lee’s original browser concept resembled current-day wikis more than Web pages, in the sense that the reader could edit and amend text just as much as passively read it. But that concept was replaced by a more secure Web experience because of the phenomena of hacking and online vandalism.

The reason for the Web’s success had already been summed up by Bush 44 years earlier in the Atlantic Monthly. He realized that in print, specialists published findings that interlaced, but without the connections ever being made. To use Bush’s words, “The means we use for threading through the maze to the momentarily important item is the same as was used in the days of the square-rigged ship” (Bush 1945, 2). Science had outgrown this mode of information sharing, and physicists were the first scientists to experiment with a new medium to meet their needs.

Because CERN was the largest Internet node in Europe, the Web became a global phenomenon in a few short years. It quickly burst out of its physics confines and into every academic discipline. Within five years of its widespread use in academia, corporations saw the vast potential of the new medium and began making commercial use of the Web. What followed was a series of refinements and standards efforts that enabled Web publishers to create vast searchable repositories of content on every imaginable subject. It also evolved beyond an immense interlinked library of hypertext to become a commerce engine and an agent of organizational and social change. Just as print evolved over the centuries, the Web continues to evolve to better meet the needs of information retrieval and sharing.

Print Content versus Web Content

We are in the midst of an accelerated version of the move from oral to print culture. In this case, we are moving from a static print culture to a dynamic Web culture. This new shift is changing the way we think. But because we are in the middle of it, we have a hard time objectively analyzing just how our thinking is changing. Also, it is a bit of a moving target: As Web change accelerates, it’s tough to encapsulate the whole of Web practice into a static medium such as this book. For that reason, we don’t seek to exhaustively show the differences between Web media and print media. Rather, we will focus on the salient features that contribute to the kind of seismic change like that of the invention of spaces between words—the sheer quantity of unstructured content at the fingertips of anyone who uses the Web.

The key facets of the Web that differ from print are as follows.

• Because the Web is so vast and complex, Web users scan content to determine relevance. They only read after they’re sure the content is relevant to them.

• Readers only determine that a page is relevant to them if it matches their use of the words on the page. If you use technical or figurative language that differs from audience expectations, they are likely to ignore your work, rather than reading it.

• Because users can land on a page from any number of starting points, especially search engines, you can’t assume that your audience has the background needed to understand your content. In a sense, it’s not your story, it’s the user’s.

• Because the Web includes a lot of bad information, Web readers are more skeptical than print readers. If you get users to read your content, you must provide clear evidence for it—preferably in the form of links to authorities on the topic.

• Web writing is not permanent. You could say it’s never finished. Because it’s relatively easy to update Web pages, Web users expect pages to do this regularly. And the Web medium gives the writer the ability to test how a page is performing and make adjustments to better target the audience.

There are many more differences between writing for print and writing for the Web. We will limit the discussion for the present purposes to these five salient differences.

Basic Information Retrieval on the Web

The most important cultural practice on the Web is that of scanning. Print readers have a relatively easy time finding the information they need. They can go to the library, which is organized in a very rigorous way to help them find information. Books are organized by genre, author, and title. Libraries have codes such as the Dewey Decimal System to help users find the exact match for the books they’re looking for. And they have computerized card catalogs, which are now nearly as sophisticated as search engines, to help them. So when readers find the books or periodicals they are looking for, they can begin reading confidently, without worrying about whether those items are relevant to their needs.

The main difference between a library and the Web is the lack of a standard organizational system for information on the Web. Numerous such systems have been tried, but none have become pervasive. The Web is like a library where everything is organized by publisher, and there are millions of publishers, who each produce information of all sorts. This is a vastly more complex universe than a library. Users typically find information using search engines on the Web, but unlike with a library card catalog, they can’t assume that the results of the search are relevant to them. Because the snippets of information that search engines display are so meager, users often must click through to the results to determine relevance. A large percentage of users won’t read a page’s contents until they scan it and determine that it is indeed relevant to their needs.

Because the Web is so vast and seemingly disorganized, Web users don’t often waste time reading. Suppose that a user enters a few key words into a search engine and gets pages upon pages of results. How does he or she decide what to read first? Typically, Web readers click results near the top of the first page of the search results, scan the pages to determine if they are relevant to them, and only after making that determination do they actually read. If a page doesn’t seem relevant within a few seconds, they click the Back button, or “bounce” off the page, back to the search results, and try another page. After bouncing off of three or four pages, readers become frustrated and will then refine their search strings to better match what is relevant to them. Jakob Nielsen (June 2008) shows that most Web users behave this way. There are outliers, but the common understanding is that you as a Web author have on average 3 to 6 seconds of scanning to demonstrate your page’s relevance to a user.

So the question is: How do you write for audiences that only give you a few seconds to determine if you’re worth their time? The answer to this question depends on the answer to another one: How does a Web audience determine the relevance of a page through scanning? We will cover that question in Chapter 3, which deals with how relevance is determined on the Web. But in order to answer the question about relevance, we must first understand features of the Web medium that differ from the print medium. Savvy Web users take advantage of these subtle features of the Web medium to help them determine relevance.

Meaning as Use on the Web

In print, writers typically define their terms up front, and use those definitions throughout a text or group of texts. In the common usage this is a matter of either using a conventional definition, or of modifying one to fit the need. These terms must fall within an acceptable range of language use in order to make sense. But print writers have control over how they use and define their terms, and they often use technical definitions for the sake of clarity. Readers must cede this control if they wish to continue making sense of what they read.

On the Web, the roles are reversed. Readers determine what they think a word or term means, and writers need to pay attention to this first and foremost. The writer is best served by keeping these conventional or community definitions in mind, because users will use them in their searches. Readers will tell you if your use of language deviates too much from the community usage. How? If you use terms for which users search in an unusual way, they will not find your pages relevant to them. And in many searches, they will find pages that clearly are not relevant. An obvious example is a search on “orange.” Novice users who search on such a generic term might get results for the fruit or the pigment. If they are shopping for orange paint, they will not find pages related to the fruit relevant to them. Or if the relevance is not clear from the snippet in the search result, users might click through to the wrong page. When this happens, they typically bounce back to the search results page and refine their search to something more promising, like “orange paint.”

Suppose that you use a term on a Web page in a way that deviates from its conventional use, in terms of search results. And suppose that you also do everything necessary to make your page rank highly for search engines when users search for that term, or keyword. Users will find your content; but they will fairly quickly find that it is irrelevant to them—they were looking for information related to the conventional use of the term. Thus, they will bounce back to the results page and never return.

Another likely scenario if you use a term unconventionally is that your page will not rank highly for that term in the first place, because the search engine algorithm will determine that it is not relevant to users searching on it. This will practically guarantee low traffic for your page. When you write for the Web, it is best to learn how your target audience uses terms and adopt their usage, rather than trying to coin terms or create technical definitions for common terms.

One way that print writers often try to make their writing interesting is to use clever puns and double meanings to spice up the language, especially in headlines. This might make for a more interesting read, especially in magazines and newspapers, but it will not help you reach your target audience. For example, an ESPN.com headline read, “Closing The Book.” The story was about the Cleveland Indians signing “closer” (a “relief pitcher” who pitches the last inning or two and “closes out” a baseball game) Kerry Wood to a free agent contract. Users searching for information on this story would not likely use the term “book” in their search queries; hence, searches might not find that story. Though the pun may make the writing more interesting, it defeats the purpose of having a story on the Web in the first place. This is one case where common print practices, such as using puns, do not translate well to the Web. It is better to have a lot of targeted traffic to pages that seem less interesting to the writer, than to have very little traffic to pages that might seem more interesting to him or her. Writing for the Web isn’t about what’s clever or interesting to the writer; it’s about what’s relevant to the reader. At least that’s the position that we take in this book.

Writing for Skeptical Web Readers

In part because there are almost as many publishers as readers on the Web (in the age of blogs and social networking sites), readers do not have the traditional sense of trust that they place in print media. Unless you happen to work for one of the few trusted sources on the Web, your Web writing must assume that the reader has to be convinced. It is not enough to simply state claims; you must also prove them. But since you have only a few seconds to demonstrate your trustworthiness to a reader who is scanning a Web page, your proof cannot be complicated. You can show your trustworthiness in other ways, though, such as by providing links to many complimentary resources, using short, punchy descriptive phrases. They themselves cannot prove your points, though; the resources must do this. But if you provide a nonthreatening environment that entices users to open the resources that show your site’s authority, you have a better chance of success than if you overwhelm them by trying to prove that authority before they’re ready.

Unlike with print, Web credibility must be earned. It takes time to develop regular visitors who trust you. And there are no shortcuts to credibility. But you can increase your chances by getting highly ranked by Google (or Bing) on your topic, which will draw users to your site. Because Google’s search results have credibility for users, they will likely give you the benefit of the doubt if they come to your site from Google. In keeping with this book’s theme, closing any credibility gap for your Web site is as much about writing for search engines as it is about writing for your audience.

Another approach that we highlight in this book deals with social media. Credibility on the Web is not assigned by individuals, but by entire communities of like-minded users. Getting these users to find and share your content with each other is the ultimate way to gain credibility on the Web. It starts with search optimization, but it continues with social media tactics that you can use to deepen your relationship with loyal readers. The ultimate goal is to become a hub of authority, so that credible members of your community will link to your pages from their sites. This not only enhances your credibility in the community, but it is perhaps the most effective way to improve your search ranking, especially for topics with a lot of competition. Having Web credibility takes time and effort, but if you follow the practices we outline in this book, you will get there eventually.

The Perpetually Unfinished Web Page

We mentioned earlier that the Web medium gives you an opportunity to understand your audience in ways you never can with print. Writing a book can seem like sending out a message in a bottle. You never know who will pick it up, read it, quote from it, and share it with colleagues. This forces print writers to form convenient fictions about who their audience is and how they will make use of the book. It also forces print writers to interest their audiences with elaborate literary devices that compel them to continue reading and follow the static information flow.

On the Web, you may not know who your audience is, but you can know how they use your information. Web metrics tools can tell you where your users came from, how long they spent on your pages, whether or not they bounced off them, and the paths they took through your pages if they stayed. If your users came from Google, you can also know what words and phrases they used to get to your pages. And if you let users make comments on your writing, you can get direct feedback.

Because it is easy to update an existing Web page, it is a common practice for Web publishers to adjust pages based on the information they get from these metrics tools. If a particular link is popular, perhaps you want to draw more attention to it. If another link is not at all popular, perhaps you want to find a different source to support your points. If users tell you they don’t like something, you can change it and thank them for the feedback. This kind of direct engagement with the audience allows Web writers to address them as real individuals rather than seeing them as convenient fictions.

Because Web publishers can treat their Web pages as dynamic, living documents that address their audiences better as time goes on, more and more Web users expect them to do this. Web audiences frown on stale content, and they will tell you this by not clicking on links and by bouncing if your content doesn’t interest them anymore. In those cases, it is your job to either update the content or take it down. Some sites provide archives to enable researchers to find bookmarked information. But your active pages can and should be tested and adjusted regularly.

Summary

We cannot emphasize strongly enough how different Web writing is from print writing. And as the Web evolves into an ever more social medium, writing for the Web is becoming as different from writing for print as writing in one language differs from writing in another. Translation from English into, say, German requires not only translating the words, but also transliteration into the culture of the German-speaking people in the target audience. In the same way, attempting to translate print writing into the Web medium requires a kind of transliteration into the culture of the Web users. For this reason, it is typically better to just write for the Web in the first place in order to appeal to the practices of Web readers. This chapter is a survey of the prevalent cultural practices of Web readers.

In a sense, the Web is a victim of its own success. Because it is relatively cheap and easy to publish information on it, writers for the Web must deal with several issues not yet seen in the print world.

• Web content is unstructured. The content itself must provide the structure. Because of this, Web users don’t read Web pages until they first discern whether the content is relevant to their needs. This differs from print content in the sense that the print world has many conventional ways of structuring publications, such as by author, by genre, or through the Dewey Decimal System. It is much less likely that readers will access an irrelevant publication from this structured system than that they will access an irrelevant Web page from a simple Web search.

• Meaning on the Web is determined by the reader rather than the writer. Because so many terms and expressions have multiple meanings, Web readers must first determine if the use of a term or expression on a page matches their expectation before deciding whether to read the content on that page or look for another page. This differs from print in the sense that authors of print publications can use their terms as they choose, while readers are required to conform their understanding to the authors’ meaning, within reason.

• On the Web, the writer is not in control of the story; the user is. Because the Web allows for all kinds of navigation paths determined by the user, the “story” could be a collection of content from multiple sources, authors and contexts. This differs from print media, in which the writer tells a story and leads the audience to follow that story, or information path. As a Web writer, you can’t assume that readers followed your prescribed navigation path to get to your content. For example, they might have landed directly on a given page from a search engine. So you must break information into small chunks and give users many ways to navigate to the ones that are relevant to them. And you cannot assume that your reader knows the contextual background information for a content module.

• Because results can be published quickly on it, the Web does not have the levels of quality control that print media typically have. For this reason, Web journals have not replaced print journals altogether in academia. And print will always occupy an important role for more permanent information. The editorial review of print journals tends to give them more credibility than publications created only for the Web. This means that Web users tend to be more skeptical than print users, although this is evolving as Web content governance evolves. But at the time of writing, most Web audiences do tend to be skeptical.

• Web writing is never finished. The writer gets the information to a certain minimum standard of quality, posts it, and begins watching the audience interact with it. Based on this interaction, the writer is expected to edit and update the content to better serve the audience.

These facts about the Web medium fundamentally change the reader/writer relationship and the concept of audience analysis at the heart of that relationship. Writing for Web readers requires surrendering control of the story and giving readers easy, clear paths to the information they seek. But it is not devoid of audience analysis. On the contrary, the Web lets writers tailor their content to the audience based on how the audience interacts with it. Even before publishing, Web writers can form a fairly accurate understanding of the word usage habits of their expected readers, based on information mined from search engine and social media usage. This book is about using that enhanced audience knowledge, which only the Web can provide, to create relevant content for your audience.