Chapter 2

Your Portfolio is Not Well Balanced

Good balance is particularly important in today's uncertain economic climate given the wide range of potential outcomes. Most investors probably agree with this argument, considering the current atypical economic environment and the considerable central bank response. Indeed, printing massive amounts of money and resorting to other unusual stimulative measures are not activities that we are used to seeing. Both the state of the economy and the reaction to conditions are undeniable signs that we do not live in normal times.

Consequently, most investors would reasonably wish to hold a well-balanced mix of asset classes. In fact, most investors (including you, most likely) feel that they already do own a well-balanced portfolio and are appropriately positioned for the present uncertainty. That disconnect is the topic of this chapter. You think your portfolio is well balanced, but it is not.

What Is Good Balance?

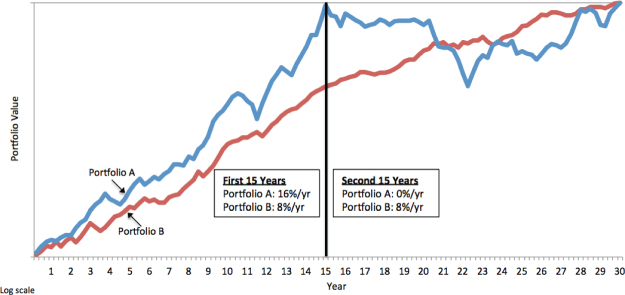

Let's begin with the definition of good portfolio balance. What does it mean to be well balanced? Most significantly, you should consider the return pattern of the portfolio over a very long time period. The return stream should be as steady as possible and should certainly not fluctuate considerably through time. Consider two portfolios that have achieved the same returns over a 30-year time frame: Portfolio A and Portfolio B, as depicted in Figure 2.1.

Figure 2.1 What Is Good Balance?

Portfolio A performed very strongly during the first 15 years and was roughly flat the ensuing 15-year period. In contrast, Portfolio B ultimately earned the same return but through a far more consistent path by delivering a similar return in both halves of the 30-year time frame.

If the two portfolios produced the same returns over the 30-year period, why should you care which you own? The reason has to do with the stability of long-term returns and the risk that you enter at an inopportune time. Let's take a 15-year investment time frame, which most would agree is long term. If you happened to invest during the right 15-year period, then you would have been very happy with Portfolio A. However, if you were unfortunate enough to have guessed wrong and had bought that portfolio during the wrong 15-year period, then you would have been quite disappointed with the outcome.

Compare the timing risk involved with Portfolio A to that of Portfolio B, which achieved the same average annual return over the same 30 years. However, this mix was able to maintain tighter dispersion from the average over time. Clearly, this is a more desirable allocation since the odds of earning close to the average are substantially improved. Even if you guess wrong and buy at the worst time, you still achieve success with Portfolio B. In this example, Portfolio A is clearly poorly balanced, whereas Portfolio B is well balanced.

These two examples may sound extreme and you may feel that they are an unrealistic comparison. You might contend that in real life the outcomes can't be that spread out. After all, 15 years is a long enough time frame to smooth out the short-term volatilities of markets and the economic climate. Favorable periods are followed by bad spells, and the cycle is repeated multiple times throughout a 15-year history such that more normal results are far more likely with any portfolio. Although this widely held viewpoint sounds reasonable, it is not reality and is not supported by actual historical results. In fact, the so-called extreme examples I provided above are far more realistic and representative of past returns and future probable outcomes. The main point to remember is that you should strive to build an asset allocation that is positioned to achieve relatively stable returns through time rather than one that is highly dependent on picking the right period in which to invest. When I encourage investors to hold well-balanced portfolios, this is the ultimate objective to which I am referring. Stable returns through all long-term time periods is what we should all strive to achieve.

The Conventional Portfolio Is Not Balanced

If your objective is to construct a portfolio mix that is expected to earn steady returns over time, then the next logical discussion point is an analysis of how the conventional portfolio fits within this context. Is the conventional portfolio well balanced? A 60/40 asset allocation (60 percent stocks and 40 percent bonds) has long been considered a balanced portfolio by most investors, professional advisors, and other experts. This mix sounds balanced because it invests in both stocks and bonds, two asset classes that are materially different from one another. One is highly volatile (stocks) and offers attractive long-term expected returns, while the other (bonds) provides stability and lowers the volatility of the total portfolio. Conventional theory posits that bonds earn less but are needed to lessen variability in returns, and stocks earn more but are far too volatile to be held alone. The balance comes from owning both. Further, since stocks earn more than bonds—the theory continues—investors should own more stocks than bonds if they have the luxury and patience to hold on for the long run. The more risk they want to take, the more stocks they should own. This is the normal thought process that has led to a conventional asset allocation mix of 60/40.

The problem with this conclusion is that a 60/40 portfolio is not only imbalanced, but it is exceedingly out of balance and much more akin to the extreme example described above. Table 2.1 lists the returns of the 60/40 asset allocation over long-term bull and bear market cycles since 1929. The return is broken down into two parts: the return of cash and the excess return above cash. Combining the two provides the total return, which is the actual return you would have experienced. Your focus should be on the excess returns above cash because that is the return you earned for taking risk. You could have just held cash and received the yield without taking any risk. The average excess return above cash of this allocation has been 4.1 percent per year since 1929, but actual experience is highly dependent on picking the right long-term period in which to invest. You would have performed much better than 4.1 percent less than half the time and much worse during the other periods.

Table 2.1 Annualized Return by Long-Term Cycle

| Period | 60/40 Portfolio Excess Return | Cash | Total Return |

| 1929–1948 | 2.2% | 0.5% | 2.7% |

| 1948–1965 | 8.4% | 2.3% | 10.8% |

| 1965–1982 | −2.3% | 7.5% | 5.2% |

| 1982–2000 | 9.2% | 6.5% | 15.6% |

| 2000–2013 | 2.7% | 2.1% | 4.8% |

| Avg. All Periods | 4.1% | 3.8% | 7.8% |

Source: Bloomberg and Bridgewater Associates.

Further observe returns for the past four decades as shown in Table 2.2. During the 1970s, and from 2000 to 2010, the 60/40 portfolio performed miserably, returning less than cash. This represents a period covering roughly half of the past four decades! I am not referring to short time periods, but rather considerable lengths of time that are certain to leave lasting adverse consequences if mismanaged. Conversely, the 1980s and 1990s produced outsized returns in the completely opposite direction as both stocks and bonds earned strong results. It should be clear at this point that the example offered at the outset of this chapter was not merely an attempt to make a point by resorting to hyperbole. It was a statement of fact that should be taken very seriously and not quickly dismissed as an unlikely scenario.

Table 2.2 Annualized Return by Decade

| Period | 60/40 Portfolio Excess Return | Cash | Total Return |

| 1970–1980 | –0.9% | 6.8% | 5.8% |

| 1980–1990 | 5.3% | 9.6% | 14.9% |

| 1990–2000 | 8.9% | 5.3% | 14.2% |

| 2000–2010 | –0.5% | 2.9% | 2.4% |

| Avg. Four Decades | 3.1% | 6.1% | 9.2% |

From a simple review of historical results, it is obvious that a conventional asset allocation is not well balanced. I have already established that the key attribute of good balance is the achievement of stable returns over time. Clearly, the 60/40 mix has not passed this simple test, as it has delivered great returns for long periods and terrible results over other extended time frames. Putting it all together, about half the time you'll love it and half the time you'll hate it. This bipolar set of outcomes is hardly representative of good balance.

Why Is It Not Balanced?

An asset allocation of 60/40 is not balanced largely because of the particular characteristics of the two asset classes used. Stocks are highly volatile, whereas bonds are not. This may not seem like a big problem, particularly since according to traditional methodologies that is the precise reason for the inclusion of these two asset classes. The total return of the portfolio is dependent on the returns of the two asset classes during each period. For instance, if stocks earn 10 percent and bonds earn 5 percent in one year, then the total portfolio that has allocated 60 percent to stocks and 40 percent to bonds will achieve an 8 percent return during that year. If stocks earn 20 percent and bonds earn 0 percent, then the total return will be 12 percent. If stocks lose 20 percent and bonds earn 5 percent, then the portfolio's value will decline by 10 percent. Table 2.3 lists the excess return of the 60/40 portfolio for each calendar year since 2000. The returns of the stock and the bond component are provided as well.

Table 2.3 Calendar-Year Excess Returns 2000–2013

| Year | Equities | Bonds | Total 60/40 Portfolio |

| 2000 | –17.8% | 5.0% | –8.7% |

| 2001 | –15.3% | 4.4% | –7.4% |

| 2002 | –24.0% | 8.5% | –11.0% |

| 2003 | 27.8% | 3.0% | 17.9% |

| 2004 | 9.2% | 2.9% | 6.7% |

| 2005 | 2.4% | –0.8% | 1.1% |

| 2006 | 9.9% | –0.7% | 5.7% |

| 2007 | 1.0% | 1.9% | 1.4% |

| 2008 | –38.3% | 3.3% | –21.7% |

| 2009 | 26.9% | 5.8% | 18.5% |

| 2010 | 15.3% | 6.4% | 11.8% |

| 2011 | 1.9% | 7.8% | 4.2% |

| 2012 | 16.0% | 4.1% | 11.2% |

| 2013 | 32.2% | –2.1% | 18.4% |

* Periods of underperformance for equities and 60/40 asset allocation are bolded.

Notice that the returns of stocks are all over the place, as can be expected. This is what it means to say that this asset class is highly volatile. It can do very well or extremely poorly and tends to produce returns year-over-year far away from its long run averages. Bonds, on the other hand, are much less volatile. Thus, their return stream ends up much closer to their long run average over shorter time frames. This is why the average return is lower than it is for stocks. If that were not the case, then investors would opt to own bonds over stocks since they could get the same return for less risk.

The key observation that should be drawn from Table 2.3 is that the total return of the portfolio is almost entirely dependent on whether stocks have performed above or below their average return. Since bonds are not very volatile, their results have little impact on the total portfolio. A bad period for bonds is not far from its average, just as a good period is not that far above it. Since stocks are so much more volatile than traditional bonds used in conventional portfolios, the total portfolio's success is highly correlated to the returns of stocks. When stocks do well, the total portfolio outperforms its average and when stocks suffer through downturns (highlighted in bold in Table 2.3), the total portfolio experiences underperformance.

To make matters worse, investors own more of the highly volatile asset class—stocks—relative to less volatile bonds. This results in poor balance because the impact of an asset class on the total portfolio is only dependent on two factors: (1) how volatile the asset class is, and (2) how much of the total portfolio is weighted toward it. For example, a portfolio that is 90 percent allocated to stocks and only 10 percent to bonds is obviously poorly balanced. This is because the 90 percent is very volatile and the 10 percent is not. However, a 60/40 mix is not much better. By overweighting stocks relative to bonds (60/40 still has 50 percent more stocks than bonds), investors are effectively and unknowingly putting all their eggs in one basket. It should actually go the other way. The more volatile asset class should get a lesser weight to make up for the fact that it is more volatile. The less volatile segment should receive a higher allocation so that its impact on the portfolio matches that of the higher-volatility asset class. At this point, I just want to introduce this sort of thinking for portfolio construction. In later chapters I will discuss this crucial concept in much greater detail. For now, you might consider adjusting the way you think about the portfolio construction process to one that incorporates an understanding of the importance of asset class volatility on portfolio balance. Most critically, this insight is often missing in the conventional approach to asset allocation.

Although most investors mistakenly believe 60/40 is well balanced, the reality is that the traditional 60/40 allocation is 99 percent correlated to the stock market! This is a fact that has been observed since 1927 over short and long time periods. This means that the success of the 60/40 portfolio is nearly entirely reliant on how the stock market performs. You can clearly see this in Table 2.3 by comparing the success of 60/40 year by year to outperformance and underperformance of equities during the same periods. This basic, undeniable attribute of the 60/40 portfolio is perhaps the single biggest oversight in investing today. Indeed, most professional investors are not aware of the extremely high correlation between a portfolio that is widely considered to be balanced and the stock market.

This imbalance is why a 60/40 portfolio can go through very long periods of underperformance, as exhibited in Table 2.1. The stock market can experience long stretches of severe underperformance, which directly leads to poor results for the 60/40 mix (which is 99 percent dependent on a good stock market return). This obvious observation has existed for nearly 100 years and will likely continue to hold true in the future.

Another important reason that the conventional 60/40 allocation is imbalanced is because its construction completely ignores the economic bias inherent in each asset class. As it turns out, both stocks and bonds are biased to do well during falling inflation climates. Therefore, 60/40 predictably does well when inflation is falling and poorly in the opposite environment. This topic will be covered at great depth later in the book.

The Flaw in Conventional Thinking

The historical results make it obvious that 60/40 is imbalanced. However, the key takeaway should be to recognize that the core issue is that the traditional thought process used to develop the conventional asset allocation is highly flawed. This is the key oversight. After all, the historical results could certainly have been different and will undoubtedly vary in the future. You can, however, learn about the issues with the thought process that led to the conventional allocation and emphasize less the actual results. Such an analysis is more likely to lead you to make improvements in how you build portfolios to give yourself a better chance to achieve long-term success.

The flawed conventional thought process is as follows: Stocks offer a higher expected return than bonds. Because they are riskier, it is reasonable to expect that the relationship between higher returns and risk will hold over time. According to the theory, it follows that the longer the time horizon investors have, the more they should allocate to the higher returning asset class (stocks). Bonds are only there to provide stability, since their returns are inferior to those of stocks over the long run. Thus, the longer the investment period, the more the investor can afford to live with ups and downs. Assessment of the appropriate asset allocation ratio is often based on factors such as the investor's age, cash flow needs, and emotional risk tolerance. Are you someone who can ride the roller coaster without emotion or are you more prone to selling at the first downturn? This combination of factors results in a portfolio that scales up and down from a starting point as low as perhaps 30 percent stocks for conservative investors, to as much as 75 percent stocks for those with more aggressive temperaments.

You should note that nowhere in the aforementioned traditional thought process is there a thought to how the volatility of the asset classes impacts the total portfolio's return stream. Moreover, there is no attention paid to the economic bias of the asset classes in the conventional approach. The emphasis is entirely on the returns of the asset classes. The only consideration of volatility is the fact that bonds are less volatile than stocks and so have a place in a portfolio merely to help achieve a lower total portfolio volatility than that of one with 100 percent stocks.

This distinction is critical. If your thinking follows conventional logic, then you are likely to end up with a portfolio as imbalanced as the traditional 60/40 mix. However, if you are trying to construct an asset allocation that is more balanced and less dependent on the success of the stock market, then you should contemplate adopting a different mind-set.

A New Lens

Instead of automatically following others, first consider viewing the crucial asset allocation decision through a new lens. Stocks have a higher return than traditional bonds because they are prepackaged to contain higher risk. You do not have to accept this prepackaged product, as you have the ability to make modifications. For instance, you can simply add leverage to a low-risk, low-return asset class such as bonds to achieve a similar return as that from stocks. This is available to you because the risk-to-return ratio for most asset classes is roughly similar. If it were not, you could simply use leverage to achieve a superior risk-return ratio. For example, if stocks offered an average return above cash of 6 percent with 20 percent volatility, and bonds provided a 3 percent return with 10 percent volatility, then you could simply double your bet on bonds by using leverage to create a similar risk-return tradeoff as stocks. You may not want to do this because of your views on the future of bond returns today, but the opportunity exists nonetheless and should be part of the analysis.

Alternatively, you can simply own twice as many bonds as stocks to neutralize the impact of volatility in the portfolio. If bonds earn half as much as stocks, then you can own twice the allocation to equalize the net effect. Finally, with bonds in particular, you can simply lengthen the duration in order to increase volatility. Longer-dated bonds are more volatile than shorter-dated debt securities and can help better balance the portfolio. I will dig into much deeper detail on these topics in later chapters. At this point, the key insight you should understand is that there are easy fixes to the prepackaged asset class limitation. Before moving to the next chapter, try to start thinking about constructing a balanced portfolio using this different perspective.

The new lens involves thinking about an asset class not as something that offers returns, but as something that offers different exposures to various economic climates. Each asset class reacts in a predictable and logical manner to various economic environments. Each asset class offers a bias to different economic conditions and each is predisposed to contain a certain level of volatility. It is these characteristics that you can emphasize in your attempt to construct a well-balanced portfolio.

Summary

Given today's unique economic climate, there is great need for strong balance in portfolios. However, the vast majority of portfolios are not well balanced. This can be seen by simply observing the makeup and long-term history of the conventional 60/40 allocation, which many investors and professionals consider to be balanced. The assumption that 60/40 is well balanced, when deeply analyzed and when incorporating a longer-term data set that includes various economic climates, is clearly not supported by history. Perhaps most believe that there is nothing that you can do to minimize exposure to the markets' inevitable ups and downs. This conclusion is simply misplaced.

In the next chapter, I discuss what truly drives asset class returns over time. The concepts that will be introduced next are designed to set the core fundamental underpinnings to help you see investing through a new lens. Through this new viewpoint, the flaws in conventional logic will become much more apparent and a novel approach to building a truly balanced portfolio will appear more logical.