Chapter 10

How to Build a Balanced Portfolio

The Step-by-Step Process

To this point we have covered the conceptual framework for constructing a balanced asset allocation. In this chapter we roll up our sleeves and dive into a simple methodology for actually creating a balanced portfolio.

The Logical Sequence behind Efficiently Weighting Asset Classes

There are two decisions you must make to create a balanced portfolio. First, you must determine which asset classes to include. This decision will be based on identifying the economic biases of various asset classes. The mix should include a variety that covers all the major potential economic outcomes: rising growth, falling growth, rising inflation, and falling inflation. Much of the book thus far has been dedicated to this topic.

After you have established which asset classes are appropriate for your portfolio, the second decision will be how much to allocate to each. An understanding of the volatility of each asset class will be an important factor in this decision. The goal of this chapter is to provide a step-by-step process to help you determine the right allocation to each asset class.

The Ideal Portfolio for Each Economic Climate

The overall goal is to build a portfolio that is by and large indifferent to shifts in the economic environment. A helpful way to construct such an allocation is to first build the ideal portfolio for each economic climate. What is the best allocation for a rising growth environment? What is the ultimate mix for a falling growth period? What about rising inflation or falling inflation climates? What is the perfect mix during each of these economic outcomes?

Using the four basic asset classes we have covered, for the rising growth environment you would simply invest all your money in stocks and commodities. The reason is that these two asset classes are biased to outperform during such an economic environment. The other two assets covered in this book—Treasuries and TIPS—would likely underperform during rising growth. Note that you would own both stocks and commodities, as opposed to just stocks, because of the uncertainty about shifts in the inflation rate. Remember that we are isolating growth in this analysis and only considering the ideal portfolio during that climate. We would like to be agnostic to the direction of inflation, which can obviously rise or fall concurrently with a rising growth environment. If both growth and inflation were to rise, then commodities would probably do best. If growth rose and inflation fell, then stocks would be biased to outperform commodities. Given these conditions, you would own both stocks and commodities and feel relatively good that your portfolio would perform quite well regardless of the inflation outcome.

Conversely, during a falling growth environment, you would want to own Treasuries and TIPS for reasons opposite to those described above. Both of these asset classes benefit from falling growth, and regardless of which way inflation goes you are protected. The same analysis follows for a period of rising inflation (during which you'd own TIPS and commodities) and falling inflation (stocks and Treasuries). Table 10.1 summarizes the ideal portfolio in each economic environment.

Table 10.1 Ideal Portfolio for Various Economic Climates

| Economic Environment | Ideal Economic Portfolio |

| Rising Growth | Stocks and Commodities |

| Falling Growth | Treasuries and TIPS |

| Rising Inflation | Commodities and TIPS |

| Falling Inflation | Stocks and Treasuries |

Combining Four Economic Portfolios into One

Since the odds of any of the four environments transpiring are about fifty-fifty (since it is relative to current market expectations), it makes sense that you should construct a portfolio that balances your allocation among these four economic portfolios. More specifically, the goal is to achieve roughly similar exposure to each of the potential economic outcomes. These are the four environments that you want to protect yourself from, and you know the assets that you should own in each of these four economic climates. Since your objective is to achieve a similar exposure (roughly, not exactly) from each of the four economic portfolios, you need to factor in the volatility when deciding how much to allocate to each. This means that you need to own more of the lower-volatility asset classes and less of the higher-volatility asset classes. Table 10.2 provides the approximate volatility of the four asset classes. Note: for simplicity I am rounding the historical volatility for this exercise. The key in this process is the relative volatility of each asset class, so even if you used precise data you would ultimately reach a similar conclusion.

Table 10.2 Volatility of Asset Classes (1927–2013)

| Asset Class | Approximate Volatility |

| Equities | 15% |

| Long-Term Treasuries | 10% |

| Long-Term TIPS | 10% |

| Commodities | 15% |

The volatility of stocks and commodities has been similar from a long-term historical perspective. Likewise, long-term TIPS and Treasuries have fared alike over the long run. Furthermore, you should observe that the volatility of stocks and commodities is about 50 percent higher than that of long-term TIPS and Treasuries (again, precision is not required in this step).

In the previous chapter I shared a visual description of these relationships, which is repeated in Figure 10.1. The idea was to indicate the increased exposure to various economic environments by increasing the number of arrows in the economic boxes based on the volatility.

Figure 10.1 Factoring in Volatility

Two Steps to Balancing the Portfolio

There are basically two steps to the balancing process. First, you need to ensure that there is balance within the four portfolios for each economic environment (which I will call the economic portfolios). Second, balance will be required across the economic portfolios, such that each portfolio has equal impact on the total portfolio. You should think of balance in terms of providing similar exposure to the various economic climates.

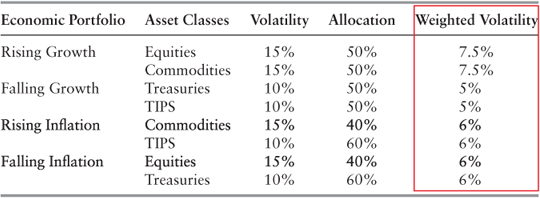

As described previously, exposure is merely a product of the volatility of each asset class and the allocation to each. I refer to this measure as weighted volatility. For each of the portfolios we have already defined two asset classes that perform best in that economic environment. The goal now is to identify a percentage allocation to the component asset classes within each economic portfolio, such that the weighted volatility of both asset classes is about the same. Table 10.3 demonstrates an appropriately balanced mix within the four economic portfolios.

Table 10.3 Step 1: Balance within the Four Economic Portfolios

The way to read Table 10.3 is to start from the far left and work your way right. Each of the four economic portfolios (one for each economic outcome) is listed in the first column. In the next column the ideal asset classes for each environment are displayed. Next, the approximate volatility of each asset class is provided. In the fourth column you will find the balanced asset allocation to each asset class within each of the four economic portfolios. For instance, in rising growth, there is a 50/50 split between equities and commodities because both asset classes have similar volatility. The fifth column provides the weighted volatility for equities and for commodities (50 percent of 15 percent volatility equals 7.5 percent weighted volatility). Thus, the rising growth economic portfolio is risk balanced since the weighted volatility of equities roughly matches that of commodities. Falling growth follows a similar logic because both Treasuries and TIPS have about the same volatility.

However, the other two environments—rising inflation and falling inflation—are a bit different. This is because the component asset classes within each portfolio exhibit different volatilities. In rising inflation, commodities are approximately 50 percent more volatile than TIPS. Thus, within this portfolio, TIPS should receive about a 50 percent greater weight than commodities in order to yield a similar weighted volatility between these two asset classes. Falling inflation follows a similar logic because of the mismatch in volatility between its component asset classes (equities and Treasuries).

The second step involves balancing across the four economic portfolios. Since you have already balanced within the four economic portfolios, you next need to do the same across each of the four segments. Using the same methodology of balancing by volatility, we determine the percentage allocation to each of the four economic portfolios that results in equal weighted volatility across the portfolios.

We begin by simply adding the weighted volatility of each asset class within each economic portfolio to come up with a total approximate volatility. For instance, in Table 10.3 the rising growth economic portfolio consists of 50 percent equities and 50 percent commodities, which yields a 7.5 percent weighted volatility to each asset class. By adding the two weighted volatilities we get about 15 percent total volatility in this economic portfolio (in reality, the total volatility is likely lower than a simple sum because of correlation benefits, but for the purposes of this exercise we are simplifying the process). Table 10.4 summarizes a well-balanced allocation breakdown across each of the four economic portfolios. You can tell the overall allocation across the portfolios is well balanced because the weighted volatility across economic portfolios (displayed in the far right column) is equal.

Table 10.4 Step 2: Balance across the Four Economic Portfolios

To come up with the final allocation to each asset class, you simply take the allocation to each of the four economic portfolios (20 percent to rising growth, 30 percent to falling growth, 25 percent to rising inflation and 25 percent to falling inflation) and break it down by asset class. This essentially involves combining step one with step two as summarized in Table 10.5.

Table 10.5 Putting It Together

| Asset Class | Economic Portfolio | Step 1: Asset Class % in Economic Portfolio | Step 2: % in Total Portfolio | Step 1 X Step 2 | Total Portfolio Allocation |

| Equities | Rising Growth | 50% | 20% | 10% | 20% |

| Falling Inflation | 40% | 25% | 10% | ||

| Commodities | Rising Growth | 50% | 20% | 10% | 20% |

| Rising Inflation | 40% | 25% | 10% | ||

| Treasuries | Falling Growth | 50% | 30% | 15% | 30% |

| Falling Inflation | 60% | 25% | 15% | ||

| TIPS | Falling Growth | 50% | 30% | 15% | 30% |

| Rising Inflation | 60% | 25% | 15% |

Table 10.5 should be read from left to right. The first two columns list each asset class and the economic environment in which they are biased to outperform. The third column lists the output of step one: balance within the four economic portfolios. For instance, equities, in step one received a 50 percent allocation in the rising growth portfolio and a 40 percent allocation in the falling inflation portfolio. The fourth column recaps the output from step two: balance across the economic portfolios. Rising growth got 20 percent in that step and falling inflation was allocated 25 percent. The fifth column in Table 10.5 is the product of step one times step two (50 percent times 20 percent equals 10 percent allocation to equities for the rising growth portfolio; the same output results for the falling inflation portfolio). The final column simply adds up the allocation in each asset class across the rising growth and falling growth buckets (10 percent plus 10 percent equals 20 percent total allocation to equities).

Using this methodology, we have constructed a balanced portfolio that consists of the following:

The Balanced Portfolio

- 20% Equities

- 20% Commodities

- 30% Long-Term Treasuries

- 30% Long-Term TIPS

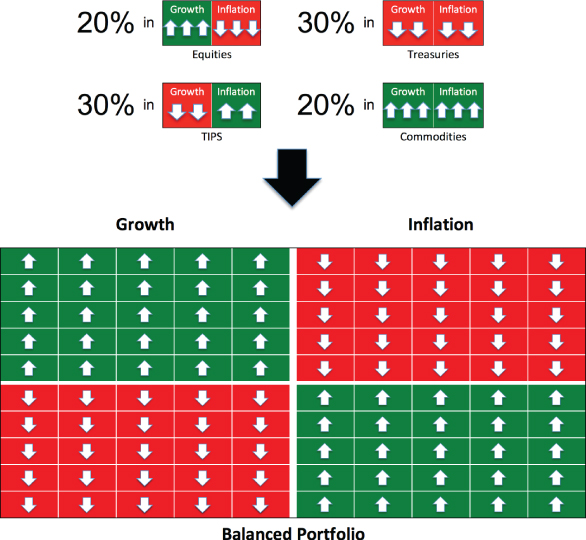

You can also view the balance that exists in this asset allocation through the box and arrows illustrations that we previously used. The total exposure to rising growth, falling growth, rising inflation, and falling inflation, as depicted in the boxes, is roughly balanced (see Figure 10.2).

Figure 10.2 The Balanced Portfolio

Don't forget that the goal of this exercise is to build an allocation that has roughly similar exposure to the different environmental drivers. That allows you to achieve a return that holds up more consistently in the face of different economic outcomes because no matter what surprise happens, there is always a portion of the portfolio that has a meaningful positive outcome. There is no need to be overly precise in setting these weights since the main benefit comes in moving in the direction of improved balance.

Not Exactly Risk-Parity

This general approach to weighting asset classes has come to be broadly known as risk-parity. The important distinction here is that risk-parity, as its name suggests, is merely focused on equalizing the risk of asset classes. Proponents of this strategy generally use many of the same asset classes as those used by more conventional asset allocation strategies and merely take the extra step of balancing the risk of each asset class. This is commonly accomplished by incorporating leverage for the lower-volatility asset classes and reducing the allocation to the higher-risk asset classes.

The missing element in many risk-parity strategies is an appreciation of the core reason to balance the volatility in asset classes in the first place. The focus should not be on balancing the risk, but on balancing the economic exposure of the portfolio. The reason is simple: It is the economic environment that is the fundamental driver of asset class returns and that is therefore the appropriate cause-effect relationship to emphasize.

For instance, it is common for a risk parity strategy to include a heavy allocation to equities and other credit sensitive asset classes such as corporate bonds. Since the asset classes used tend to perform similarly in various economic climates (most do well during rising growth and falling inflation and poorly during the opposite environments), the fact that the asset classes are risk balanced does not lead to strong portfolio balance.

Analyzing 60/40 through the Same Lens

In sum, the impact of an asset class on the portfolio's total return is simply a function of three factors:

- Its economic bias

- Its volatility

- Its weighting in the portfolio

If all you did was invest in 10 different asset classes that shared exactly the same economic bias, you might feel that you are well diversified because of the large number of holdings. However, when you go through the steps I have described to build a balanced portfolio, you will discover that it cannot be done. They all fit into the same categories, and therefore, regardless of the other two factors (volatility and weight), you don't have enough tools in your kit to create a well-balanced asset allocation. Also, consider a situation in which you had selected four asset classes with different biases but one was much more volatile than the rest. Perhaps one had high volatility while the others were low-volatility assets. That scenario would also make it challenging to build good balance because of the significant volatility mismatch. Finally, even if you have the appropriate asset classes with comparable volatility, you have to ensure that the weighting is appropriate in order to obtain similarly weighted volatility for the four economic climate portfolios. All three factors are equally deserving of your attention in this process.

The balanced portfolio framework presented here can be applied to any portfolio. Once you have determined the bias, the volatility, and the weight, you can assess the balance of the portfolio to the various economic environments. By observing the imbalance in a portfolio from the balanced portfolio perspective, you will be able to predict fairly reliably in which environments it will outperform and underperform. You obviously do not have to guess when it will do well or poorly, just under what circumstances these results are likely. You can also be sure that the imbalanced portfolio will suffer through long episodes of significant underperformance.

Taking the framework described here and applying it to the traditional 60/40 allocation will reveal some vulnerabilities of that portfolio. Table 10.6 applies the same framework just described to a combined portfolio with a 60 percent allocation to equities and a 40 percent allocation to core bonds. Importantly, note that the core bond portfolio is about half as volatile as the long-term Treasuries portfolio due to its shorter duration. This lower volatility actually hurts the balance in the combined portfolio because of its smaller impact during falling growth environments, as you can observe in Table 10.6.

Table 10.6 Using the Balanced Framework to See That 60/40 Is Highly Imbalanced

Table 10.6 considers the three key variables: economic bias, volatility, and allocation. Each portfolio (rising growth, falling growth, rising inflation, and falling inflation) is represented by one or both of the asset classes in the 60/40 portfolio. Each of these asset classes exhibits a certain volatility characteristic as summarized in the table. By combining the volatility and the allocation to that particular asset class, you can observe a weighted volatility for each portfolio. For instance, rising growth has a high weighted volatility relative to the rest because it is represented by equities, which have both high volatility and high allocation in the 60/40 mix. The only falling growth asset is core bonds, which have a low volatility. The medium allocation of 40 percent to this segment does not move the needle much in terms of weighted volatility because of the significantly lower volatility relative to equities. No rising inflation assets are included in this allocation so that portfolio has no representation. Finally, both equities and core bonds are biased to outperform during falling inflation periods so the entire 60/40 asset allocation benefits from this environment.

By putting all this together and observing the column highlighted at the far right you are able see how lopsided the 60/40 portfolio is. There is no exposure to rising inflation and very little to falling growth. Essentially, the portfolio should be reliably expected to perform well during rising growth and falling inflationary periods and very poorly in the opposite environments. Unsurprisingly, the actual results are consistent with this expectation. The wide range of historical returns during various economic climates was presented in Chapter 2. Since half the time negative outcomes dominate the environment, the 60/40 mix is biased to do poorly about half of the time. Clearly, this is not well balanced, despite popular belief to the contrary.

Viewed in terms of the boxes and arrows figures, as displayed in Figure 10.3, the imbalance in the 60/40 allocation is also easily observable.

Figure 10.3 The Imbalance of 60/40

Summary

Minimal data has been used thus far in this book. This was intentional, as my goal was to focus on the conceptual linkages rather than resort to a backfilled argument twisting historical results in favor of this approach. It is the logic that is most compelling, endures over time, and creates confidence about the reliability of the approach going forward. You should consider whether the thought sequence is reasonable and makes more sense than alternative approaches to building your asset allocation. Think about all the possibilities of the future economic environment and whether your current portfolio can withstand the potential shocks. The vast majority of portfolios would fail this simple test.