The Evolution of Management Models

The Competing Values Framework

Organizing the Learning Process—ALAPA

Core Competency: Thinking Critically

Becoming a more effective manager and leader is a life-long process in learning to transcend paradox. A paradox exists when two seemingly inconsistent or contradictory ideas are actually both true. For example, the claim that "to be a good leader, you must be a good follower" is paradoxical because leaders and followers are generally thought to be engaged in opposite types of behaviors. It also seems paradoxical that so many books have been written about how to become a better manager when most people would agree that you cannot learn how to manage people by reading books.

The competing values approach to management outlined in this text is grounded on the idea that to be effective, managers must navigate a world filled with paradoxes. Managers are often called on to do things that at first glance appear to be mutually exclusive. For example, they must focus on the future at the same time that they pay attention to the present. Managers must meet the needs of their employees while pushing those same employees to do more with less to satisfy increasingly demanding customers ever more quickly. Managers must encourage innovation and risk-taking while ensuring the stability and continuity of the organization. In short, managers must embrace a diverse set of values that often appear to be contradictory. The competing values approach to management looks for ways to transcend paradox and redefine what is possible.

For most people, transcending paradox requires some serious rethinking of existing beliefs. We all have beliefs, and we all make assumptions about the right way to do things. This is certainly true when it comes to managerial leadership. Although our beliefs and assumptions can make us effective, they can sometimes make us ineffective (House & Podsakoff, 1994). When they do make us ineffective, it often is hard to understand why—particularly when those beliefs seemed to work so well in the past. We are not usually very experienced at examining our basic beliefs and assumptions. Nor are we very experienced at adopting new assumptions or learning skills and competencies that are associated with those new assumptions. Often it takes a crisis to stimulate such change. Consider the following case.

I have always seen myself as a man who gets things done. After 17 years with a major pharmaceutical company, I was promoted to general manager in the international division. I was put in charge of all Southeast Asian operations. The unit seemed pretty sloppy to me. From the beginning I established myself as a tough, no-nonsense leader. If someone came in with a problem, he or she knew to have the facts straight or risk real trouble. After three months I began to feel like I was working myself to exhaustion, yet I could point to few real improvements. After six months or so, I felt very uneasy but was not sure why.

One night I went home and my wife greeted me. She said, "I want a divorce." I was shocked and caught off balance. To make a long story short, we ended up in counseling.

Our counselor taught me how to listen and practice empathy. The results were revolutionary. I learned that communication happens at many levels and that it's a two-way process. My marriage became richer than I had ever imagined possible.

I tried to apply what I was learning to what was going on at work. I began to realize that there was a lot going on that I didn't know about. People couldn't tell me the truth because I would chop their heads off. I told everyone to come to me with any problem so that we could solve it together. Naturally, no one believed me. But after a year of proving myself, I am now known as one of the most approachable people in the entire organization. The impact on my division's operation has been impressive.

The man in the preceding case had a problem of real significance. The lives of many people, including subordinates, superiors, customers, and even his family members, were being affected by his actions. He was less successful than he might have been because of his beliefs about what a leader is supposed to do. For him, good management meant tight, well-organized operations run by tough-minded, aggressive leaders. His model was not all wrong, but it was inadequate. It limited his awareness of important alternatives and, thus, kept him from performing as effectively as he might have. Fortunately, this man was able both to rethink his beliefs and to alter his behavior to reflect a more complex and effective approach to management.

It turns out that nearly everyone has beliefs or viewpoints about what a manager should do. In the study of management, these beliefs are sometimes referred to as models. There are many different kinds of models. Although some are formally written or otherwise explicit, others, like the assumptions of the general manager, are informal. Because models affect what happens in organizations, we need to consider them in some depth.

Models are representations of a more complex reality. A model airplane, for example, is a physical representation of a real airplane. Models help us to represent, communicate ideas about, and better understand more complex phenomena in the real world.

A model that attempts to describe a social phenomenon represents a set of assumptions about what is happening and why. By giving us a general way of seeing and thinking about that phenomenon, the model provides us with a particular perspective about a more complex reality. Although models can help us to see some aspects of a phenomenon, they can also blind us to other aspects. The general manager mentioned previously, for example, had such strongly held beliefs about order, authority, and direction that he was unable to see some important aspects of the reality that surrounded him.

Unfortunately, our models of management are often so tied to our identity and emotions that we find it very difficult to learn about and appreciate different models. Because of the complexity of life, however, we often need to call upon more than one model. When we can see and evaluate more alternatives, our degree of choice and our potential effectiveness can be increased (Senge, 1990).

The models held by individuals often reflect models held by society at large. During the twentieth century a number of management models emerged. Understanding these models and their origins can give managers a broader understanding of behavior in organizations and a wider array of choices.

Our models and definitions of management keep evolving. As societal values change, existing viewpoints alter, and new models of management emerge (Fabian, 2000). These new models are not driven simply by the writings of academic or popular writers; or by managers who introduce an effective new practice; or by the technical, social, or political forces of the time. These models emerge from a complex interaction among all these factors. In this section, we will look at four major management models and how they evolved from the changing conditions of the twentieth century. Table I.1 at the end of this section provides a summary of all four models. The discussion below draws on the historical work of Mirvis (1985). Because exact dates are not critical for our purposes, we have used time periods of 25 years to simplify the discussion. Also keep in mind that although new models typically emerge in response to problems with earlier models, the emergence of each new model does not mean that old models were completely wrong and were forgotten. Rather, some aspects of earlier models are still very relevant. Just as important, many people continue to hold onto the beliefs and assumptions they developed using an earlier model, so their decisions continue to reflect the assumptions of that earlier model.

The first 25 years of the twentieth century were a time of exciting growth and progress that ended in the high prosperity of the Roaring Twenties. As the period began, the economy was characterized by rich resources, cheap labor, and laissez-faire policies. In 1901, oil was discovered in Beaumont, Texas. The age of coal became the age of oil and, soon after, the age of inexpensive energy. Technologically, it was a time of invention and innovation as tremendous advances occurred in both agriculture and industry. The work force was heavily influenced by immigrants from all over the world and by people leaving the shrinking world of agriculture. The average level of education for these people was 8.2 years. Most were confronted by serious financial needs. There was little, at the outset of this period, in terms of unionism or government policy to protect workers from the demanding and primitive conditions they often faced in the factories.

One general orientation of the period was Social Darwinism: the belief in "survival of the fittest." Given this orientation, it is not surprising that Acres of Diamonds, by Russell Conwell, was a very popular book of the time. The book's thesis was that it was every man's Christian duty to be rich. The author amassed a personal fortune from royalties and speaking fees.

These years saw the rise of the great individual industrial leaders. Henry Ford, for example, not only implemented his vision of inexpensive transportation for everyone by producing the Model T, but he also applied the principles of Frederick Taylor to the production process. Taylor was the father of scientific management (see Theoretical Perspective I.1). He introduced a variety of techniques for "rationalizing" work and making it as efficient as possible. Using Taylor's ideas, Henry Ford, in 1914, introduced the assembly line and reduced car assembly time from 728 hours to 93 minutes. In six years Ford's market share went from just under 10 percent to just under 50 percent. The wealth generated by the inventions, production methods, and organizations themselves was an entirely new phenomenon.

Rational Goal Model. It was in this historical context that the first two models of management began to emerge. The first is the rational goal model. The symbol that best represents this model is the dollar sign, because the ultimate criteria of organization effectiveness are productivity and profit. The basic means-ends assumption in this approach is the belief that clear direction leads to productive outcomes. Hence there is a continuing emphasis on processes such as goal clarification, rational analysis, and action taking. The organizational climate is rational economic, and all decisions are driven by considerations of "the bottom line." If an employee of 20 years is only producing at 80 percent efficiency, the appropriate decision is clear: Replace the employee with a person who will contribute at 100 percent efficiency. In the rational goal model the ultimate value is achievement and profit maximization. To ensure that those goals are met, managers are expected to be decisive and task-oriented.

Stories abound about the harsh treatment that supervisors and managers inflicted on employees during this time. In one manufacturing company, for example, they still talk today about the toilet that was once located in the center of the shop floor and was surrounded by glass windows so that the supervisor could see who was inside and how long the person stayed.

Internal Process Model. The second model is called the internal process model. While its most basic hierarchical arrangements had been in use for centuries, during the first quarter of the twentieth century it rapidly evolved into what would become known as the "professional bureaucracy." The basic notions of this model would not be fully codified, however, until the writings of Max Weber and Henri Fayol were translated in the middle of the next quarter-century. This model is highly complementary to the rational goal model. Here the symbol is a pyramid, and the criteria of effectiveness are stability and continuity. The means-ends assumption is based on the belief that routinization leads to stability. The emphasis is on processes such as definition of responsibilities, measurement, documentation, and record keeping. The organizational climate is hierarchical, and all decisions are colored by the existing rules, structures, and traditions. If an employee's efficiency falls, control is increased through the application of various policies and procedures. In this model managers are expected to be technically expert and highly dependable, focusing on coordinating and monitoring workflows for efficiency and effectiveness.

The second quarter of the century brought two events of enormous proportions. The stock market crash of 1929 and World War II would affect the lives and outlook of generations to come. During this period the economy would boom, crash, recover with the war, and then, once again, offer bright hopes. Technological advances would continue in all areas, but particularly in agriculture, transportation, and consumer goods. The rational goal model continued to flourish. With the writings of Henri Fayol, Max Weber, and others, the internal process model (see Theoretical Perspectives I.2 and I.3) would be more clearly articulated. Yet, even while this was being accomplished, it started to become clear that the rational goal and internal process models were not entirely appropriate to the demands of the times.

Some fundamental changes began to appear in the fabric of society during the second quarter of the century. Unions, now a significant force, adhered to an economic agenda that brought an ever-larger paycheck into the home of the American worker. Industry placed a heavy emphasis on the production of consumer goods. By the end of this period, new labor-saving machines were beginning to appear in homes. There was a sense of prosperity and a concern with recreation as well as survival. Factory workers were not as eager as their parents had been to accept the opportunity to work overtime. Neither were they as likely to give unquestioning obedience to authority. Hence managers were finding that the rational goal and internal process models were no longer as effective as they once were.

Given the shortcomings of the first two models, it is not surprising that one of the most popular books written during this period was Dale Carnegie's How to Win Friends and Influence People. It provided some much-desired advice on how to relate effectively to others. In the academic world, Chester Barnard pointed to the significance of the "informal" organization and the fact that informal relationships, if managed properly, could be powerful tools for the manager. Also during this period Elton Mayo and Fritz Roethlisberger carried out their work in the famous Hawthorne studies. One well-known experiment carried out by these two researchers, concerned levels of lighting. Each time they increased the levels of lighting, employee productivity went up. However, when they decreased the lighting, productivity also went up. They eventually concluded that what was really stimulating the workers were the attention being shown them by the researchers. The results of these studies were also interpreted as evidence of a need for an increased focus on the power of relationships and informal processes in the performance of human groups.

Human Relations Model. By the end of the second quarter of the century, the emerging orientation was the human relations model. In this model, the key emphasis is on commitment, cohesion, and morale. The means-ends assumption is that involvement results in commitment and the key values are participation, conflict resolution, and consensus building. Because of an emphasis on equality and openness, the appropriate symbol for this model is a circle. The organization takes on a clanlike, team-oriented climate in which decision-making is characterized by deep involvement. Here, if an employee's efficiency declines, managers take a developmental perspective and look at a complex set of motivational factors. They may choose to alter the person's degree of participation or opt for a host of other social psychological variables. Managers are expected to be empa-thetic and open to employee opinions; key activities include mentoring individuals and facilitating group and team processes.

In 1949, this model was far from crystallized, and it ran counter to the assumptions in the rational goal and internal process models. Hence it was difficult to understand and certainly difficult to practice. Attempts often resulted in a kind of authoritarian benevolence. It would take well into the next quarter-century for research and popular writings to explore this orientation and for managerial experiments to result in meaningful outcomes in large organizations.

The period 1951 to 1975 began with the United States as the unquestioned leader of the capitalist world. It ended with the leadership of the United States in serious question. During this period the economy experienced the shock of the oil embargo in 1973. Suddenly assumptions about cheap energy, and all the life patterns upon which they were based, were in danger. By the late 1970s the economy was suffering under the weight of stagnation and huge government debt. At the beginning of this period, "made in Japan" meant cheap, low-quality goods of little significance to Americans. By the end, Japanese quality could not be matched, and Japan was making rapid inroads into sectors of the economy thought to be the sacred domain of American companies. Even such traditionally American manufacturing areas as automobile production were dramatically affected. There was also a marked shift from a clear product economy to the beginnings of a service economy.

Technological advances began to occur at an ever-increasing rate. At the outset of the third quarter of the century, the television was a strange device. By the end of this period, television was the primary source of information, and the computer was entering the life of every American. At the beginning of the 1960s, NASA worked to accomplish the impossible dream of putting a man on the moon, but then Americans became bored with the seemingly commonplace accomplishments of the space program.

Societal values also shifted dramatically. The 1950s were a time of conventional values. Driven by the Vietnam War, the 1960s were a time of cynicism and upheaval. Authority and institutions were everywhere in question. By the 1970s the difficulty of bringing about social change was fully understood. A more individualistic and conservative orientation began to take root.

In the workforce, average education jumped from the 8.2 years at the beginning of the century to 12.6 years. Spurred by considerable prosperity, workers in the United States were now concerned not only with money and recreation but also with self-fulfillment. Women began to move into professions that had been closed to them previously. The agenda of labor expanded to include social and political issues. Organizations became knowledge-intense, and it was no longer possible to expect the boss to know more than every person he supervised.

By now the first two models were firmly in place, and management vocabulary was filled with rational management terms, such as management by objectives (MBO) and management information system (MIS). The human relations model, however, was also now familiar. Many books about human relations became popular during this period, further sensitizing the world to the complexities of motivation and leadership. Experiments in group dynamics, organizational development, sociotechnical systems, and participative management flourished.

In the mid-1960s, spurred by the ever-increasing rate of change and the need to understand how to manage in a fast-changing, knowledge-intense world, a variety of academics began to write about still another model. People such as Katz and Kahn at the University of Michigan, Lawrence and Lorsch at Harvard, as well as a host of others, began to develop the open systems model of organization. This model was more dynamic than others. The manager was no longer seen as a rational decision maker controlling a machinelike organization. The research of Mintzberg (1975), for example, showed that in contrast to the highly systematic pictures portrayed in the principles of administration (see Theoretical Perspective I.2), managers live in highly unpredictable environments and have little time to organize and plan. They are, instead, bombarded by constant stimuli and forced to make rapid decisions. Such observations were consistent with the movement to develop contingency theories (see Theoretical Perspective I.4). These theories recognized that the simplicity of earlier approaches went too far.

Open Systems Model. In the open systems model, the organization is faced with a need to compete in an ambiguous and competitive environment. The key criteria of organizational effectiveness are adaptability and external support. Because of the emphasis on organizational flexibility and responsiveness, the symbol here is the amoeba. The amoeba is a very responsive, fast-changing organism that is able to respond to its environment. The means-ends assumption is that continual adaptation and innovation lead to the acquisition and maintenance of external resources. Key processes are political adaptation, creative problem solving, innovation, and the management of change. The organization has an innovative climate and is more of an "adhocracy" than a bureaucracy. Risk is high, and decisions are made quickly. In this situation common vision and shared values are very important. Here, if an employee's efficiency declines, it may be seen as a result of long periods of intense work, an overload of stress, and perhaps a case of burnout. In addition to being creative and innovative, the manager is expected to use power and influence to initiate and sustain change in the organization.

In the 1980s it became apparent that American organizations were in deep trouble. Innovation, quality, and productivity all slumped badly. Japanese products made astounding advances as talk of U.S. trade deficits became commonplace. Reaganomics and conservative social and economic values fully replaced the visions of the Great Society. In the labor force, knowledge work became commonplace and physical labor rare. Labor unions experienced major setbacks as organizations struggled to downsize their staffs and increase quality at the same time. The issue of job security became increasingly prominent in labor negotiations. Organizations faced new issues, such as takeovers and downsizing. One middle manager struggled to do the job previously done by two or three. Burnout and stress became hot topics.

Peters and Waterman published a book that would have extraordinary popularity. In Search of Excellence attempted to chronicle the story of those few organizations that were seemingly doing it right. It was really the first attempt to provide advice on how to revitalize a stagnant organization and move it into a congruent relationship with an environment turned upside down. Like Carnegie's book, which focused attention on the previously neglected topic of the importance of people in organizations, In Search of Excellence addressed and made clear the most salient unmet need of the time: how to manage in a world where nothing is stable.

In such a complex and fast-changing world, simple solutions became suspect. None of the four models, discussed earlier and summarized in Table offered a sufficient answer, not even the more complex open systems approach. It had become clear that none of the existing management models was adequate. A new approach to understanding effective management was needed. It was during this period that the competing values framework, which serves as the organizing structure for this textbook, was first developed and tested.

Table I.1. Characteristics of the Four Management Models

Rational Goal | Internal Process | Human Relations | Open Systems | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Symbol | $ | Δ | ||

Criteria of effectiveness | Productivity, profit | Stability, continuity | Commitment, cohesion, morale | Adaptability, external support |

Means—ends theory | Clear direction leads to productive outcomes | Routinization leads to stability | Involvement results in commitment | Continual adaptation and innovation lead to acquiring and maintaining external resources |

Action imperative Emphasis Climate | Compete Goal clarification, rational analysis, and action taking | Control Defining responsibility, measurement, documentation | Collaborate Participation, conflict resolution, and consensus building | Create Political adaptation, creative problem solving, innovation, change management |

Climate | Rational economic: "the bottom line" | Hierarchical | Team oriented | Innovative, flexible |

As the twentieth century drew to a close, the rate of change rose to new heights. Longstanding political and business institutions began to crumble. The Berlin Wall came tumbling down. A short time later the USSR itself disintegrated. In the United States some of the most powerful and admired corporations seemed strong one day and in deep difficulty the next. In the new global economy nothing seemed predictable. This was exacerbated by the emergence of the Internet and e-commerce. In the meantime, employees with the right mix of competencies and abilities were in short supply. In 2000, a survey of executives' concerns ("Survey of Pressing Problems," 2000) indicated that the most pressing problems were the following:

Attracting, keeping, and developing good people

Thinking and planning strategically

Maintaining a high-performance climate

Improving customer satisfaction

Managing time and stress

Staying ahead of the competition

Maintaining work and life balance

Improving internal processes

Stimulating innovation

During the next ten years, the world continued to change. In 2001 the attack on the World Trade Center took us into the new world of constant terrorist threats. The emergence of China shifted how we looked at global business. The disaster on Wall Street, the near collapse of the banking system and general crisis in the world economy, turned corporate life upside down. In 2010, with its high rate of unemployment, it is hard to imagine that the number one concern in 2000 was attracting and keeping people.

Today executives ask us how they can manage in a world of volatility, complexity, and ambiguity. They want to know how to get cross-boundary cooperation as they seek to continually change their organizational culture. They are looking for ways to obtain employee motivation and loyalty in an environment where they cannot promise long-term job security. These questions reflect an underlying concern— the need to achieve organizational effectiveness in a highly dynamic environment filled with complexity, ambiguity, and paradoxical demands. The competing values framework is a time-tested, powerful tool that can assist managers as they grapple with these issues.

Complex situations require complex responses. Sometimes organizations benefit from stability, and sometimes they benefit from change. Often organizations need both stability and change at the same time. In contrast to earlier approaches, the development of the competing values framework did not assume that stability and change were mutually exclusive—an either-or decision. Eliminating that assumption was the key to developing an integrated model that focused on "both-and" assumptions, where contrasting behaviors could be needed and enacted at the same time (Quinn, Kahn & Mandl, 1994). This new, apparently paradoxical assumption, is at the heart of the competing values framework—an approach that views each of the four models as elements of a larger, integrated model. This book is organized around that framework.

At first, the models discussed earlier seem to be four entirely different perspectives or domains. However, they can be viewed as closely related and interwoven. They are four important subdomains of a larger construct: organizational effectiveness. Each model within the construct of organizational effectiveness is related. Depending on the models and combinations of models we choose to use, we can see organizational effectiveness as simple and logical, as dynamic and synergistic, or as complex and paradoxical. Taken alone, no one of the models allows us the range of perspectives and the increased choice and potential effectiveness provided by considering them all as part of a larger framework.

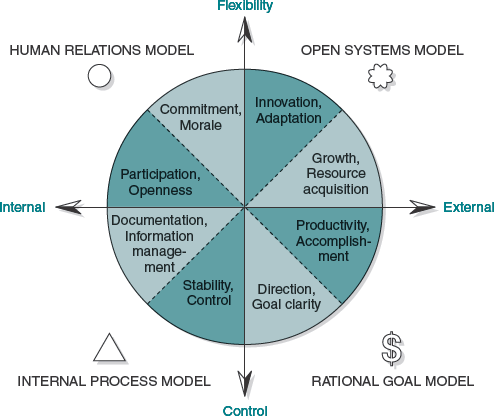

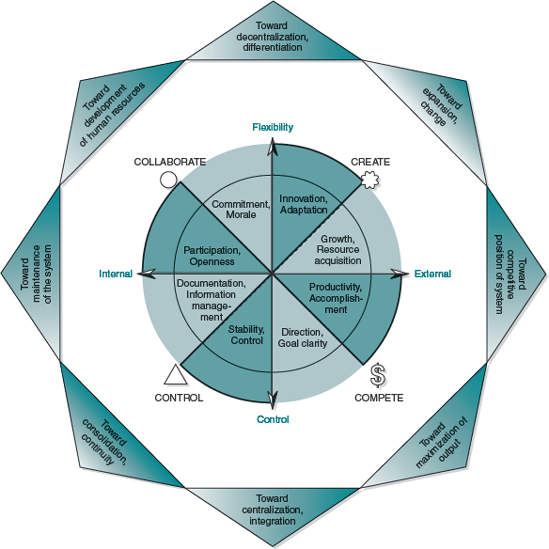

The relationships among the models can be seen in terms of two axes. In Figure I.1 the vertical axis ranges from flexibility at the top to control at the bottom. The horizontal axis ranges from an internal organizational focus at the left to an external focus at the right. Each of the earlier management models fits in one of the four quadrants.

The human relations model, for example, stresses the criteria shown in the upper-left quadrant: participation, openness, commitment, and morale. The open systems model stresses the criteria shown in the upper-right quadrant: innovation, adaptation, growth, and resource acquisition. The rational goal model stresses the criteria shown in the lower-right quadrant: direction, goal clarity, productivity, and accomplishment. The internal process model, in the lower-left quadrant, stresses documentation, information management, stability, and control.

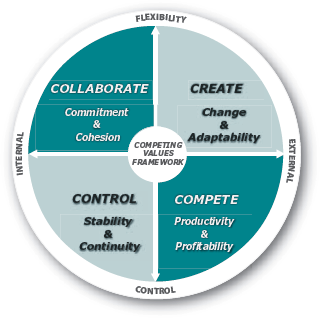

To translate these four theoretical models into management practice, we have labeled each quadrant according to the central action focus related to each model: Collaborate for the human relations model, Control for the internal process model, Compete for the rational goal model, and Create for the open systems model. We have also assigned different colors to each quadrant: yellow for Collaborate, red for Control, blue for Compete, and green for Create. Master managers do not view the world in terms of "black/white" or "either/or" and thus are able to engage in practices that support all four of these foci. Throughout the text we refer to the quadrants by either their associated action imperative or the related management model. Keep in mind, however, that these labels are just a convenient shorthand for referring to a complex set of interrelated activities associated with achieving the goals associated with different effectiveness criteria.

Figure I.1. Competing values framework: effectiveness criteria. Each of the four models of organizing in the competing values framework assumes different criteria of effectiveness. Here we see the criteria in each model; the labels on the axes show the qualities that differentiate each model. Source: R. E. Quinn, Beyond Rational Management (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1988), 48. Used with permission.

As can be seen in Figure I.2, some general values are also reflected in the framework. These appear on the outer perimeter. Expansion and change are in the upper-right corner and contrast with consolidation and continuity in the lower-left corner. On the other hand, they complement the neighboring values focusing on decentralization and differentiation at the top and achieving a competitive position of the overall system to the right. Each general value statement can be seen in the same way.

Each model has a perceptual opposite. The human relations model, defined by flexibility and internal focus, stands in stark contrast to the rational goal model, which is defined by control and external focus. In the first, for example, people are inherently valued. In the second, people are of value only if they contribute greatly to goal attainment. The open systems model, defined by flexibility and external focus, runs counter to the internal process model, which is defined by control and internal focus. While the open systems model is concerned with adapting to the continuous change in the environment, the internal process model is concerned with maintaining stability and continuity inside the system.

Parallels among the models are also important. The human relations and open systems models share an emphasis on flexibility. The open systems and rational goal models share an emphasis on external focus. The rational goal and internal process models emphasize control. And the internal process and human relations models share an emphasis on internal focus.

We will use this framework, which includes four different models of management, throughout the book to organize our discussion of different core competencies required for effective management. This integrated management model is called the competing values framework because the criteria within the four models seem at first to carry conflicting messages (Figure I.2). We want our organizations to be adaptable and flexible, but we also want them to be stable and controlled. We want our internal processes to be standardized and efficient, but we also want to be able to change and innovate so we can adapt operations to shifting external conditions. We want to value and respect employees as our most important resources, but we also want to establish plans and set goals that are likely to be very demanding. In any real organization all of these concerns are valid.

In contrast to earlier models of management, the competing values framework suggests that these opposing concerns can and should be addressed in real systems. Although we tend to think of these criteria, values, and assumptions as opposites, the competing values framework recognizes that they are not mutually exclusive. Rather than valuing one perspective over others and devaluing or discounting opposing perspectives, it is possible and, in fact, desirable, to perform effectively using the four opposing models simultaneously.

Figure I.2. Eight general orientations in the competing values framework. The eight general values that operate in the competing values framework are shown in the triangles on the perimeter. Each value both complements the values next to it and contrasts with the one directly opposite it. Source: R. E. Quinn, Beyond Rational Management (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1988), 48. Used with permission.

The four models in the framework represent the unseen values over which people, programs, policies, and organizations live and die. Like the pharmaceutical executive at the outset of this introduction, we often blindly pursue values in one of the models without considering the values in the others. As a result, our choices and our potential effectiveness are reduced.

To be effective in the long run, managers must engage in a variety of types of behaviors. As a convenient shorthand, we use the labels Collaborate, Control, Compete, and Create to refer to the different quadrants of the competing values framework and to represent the types of actions managers need to engage in. Keep in mind, however, that these four action imperatives are broad categories of behaviors and that the specific practices that managers must engage in will differ depending on the specific circumstances.

One of the key strengths of the competing values framework is that the model itself is flexible enough to accommodate change and still provides enough structure to help guide behavior. For example, Lawrence, Lenk, and Quinn (2009) recently used a sample of 528 managers to re-examine the basic structure of the competing values framework. Their findings supported the fundamental structure of the competing values framework that was originally reported by Quinn and Rohrbaugh (1983). When looking at specific measures, however, Lawrence, et al., found a greater emphasis on speed in the Compete quadrant and on ensuring compliance with policies in the Control quadrant than had been reported in earlier studies. These findings are consistent with the fundamental assumptions of the competing values framework and also make sense in light of changes that have taken place in the business environment over the past 25 years.

For managers, like everyone else, the world keeps changing. It changes from hour to hour, day to day, and week to week. The strategies that are effective in one situation are not necessarily effective in another. Even worse, the strategies that were effective yesterday may not be effective in the same situation today. Managers tend to become trapped in their own style and in the organization's cultural values. They tend to employ very similar strategies in a wide variety of situations.

The overall competing values framework, based on the four models described here, can increase effectiveness by helping managers expand their perspectives. Each model in the framework suggests value in different, even opposite, strategies. The framework reflects the complexity confronted by people in real organizations. It therefore provides a tool to broaden thinking and to increase choice and effectiveness. This, however, can only happen if three challenges are met. We must:

Appreciate both the values and the weaknesses of each of the four models

Acquire and use multiple competencies associated with each model

Dynamically integrate competencies from each of the models with the managerial situations that we encounter

When a person meets challenge 1 above and comes to understand and appreciate each of the four models, it suggests she has learned something at the conceptual level and has increased her cognitive complexity as it relates to managerial leadership. A person with high cognitive complexity regarding a given phenomenon is a person who can see that phenomenon from many perspectives. The person is able to think about the phenomenon in sophisticated, rather than simple, ways. Increased complexity at the conceptual level is the primary objective in most traditional management courses. Meeting challenge 1, however, does not mean someone has the ability to be an effective managerial leader. Knowledge is not enough.

To increase effectiveness, a managerial leader must meet challenges 2 and 3. Meeting these challenges leads to an increase in behavioral complexity. The term behavioral complexity was coined by Hooijberg and Quinn (1992) to reflect the capacity to draw on and use competencies and behaviors from the different models. Behavioral complexity builds on the notion of cognitive complexity and is defined as "the ability to act out a cognitively complex strategy by playing multiple, even competing, roles in a highly integrated and complementary way" (p. 164).

Several studies suggest a link between behavioral complexity and effective performance. In a study of 916 CEOs, Hart and Quinn (1993) found that the ability to play multiple and competing roles produced better firm performance. The CEOs with high behavioral complexity saw themselves as focusing on broad visions for the future (open systems model), while also providing critical evaluation of present plans (internal process model). They also saw themselves attending to relational issues (human relations model), while simultaneously emphasizing the accomplishment of tasks (rational goal model). The firms with CEOs having higher behavioral complexity produced the best firm performance, particularly with respect to business performance (growth and innovation) and organizational effectiveness. The relationships held regardless of firm size or variations in the nature of the organizational environment.

In a study of middle managers in a Fortune 100 company, Denison, Hooijberg, and Quinn (1995) found behavioral complexity, as assessed by the superior of the middle manager, to be related to the overall managerial effectiveness of the manager, as assessed by subordinates. In a similar study, behavioral complexity was related to managerial performance, charisma, and the likelihood of making process improvements in the organization (Quinn, Spreitzer & Hart, 1992). Lawrence et al. (2009) conducted further tests on the psychometric properties of measures of behavioral complexity in an instrument that was based on the competing values framework. They also demonstrated that higher levels of behavioral complexity as measured by a 36-item CVF Managerial Behavior Instrument were correlated with higher levels of managerial performance.

An Important Caveat about Organization Culture. Before we turn to more specific competencies for managers, it is important to note that what is considered effective performance by a manager in practice is likely to depend less on the prescriptions of management theory and research and more on the existing norms and values of that manager's particular organization. For example, if an organization has a strong culture oriented toward control, managers who seek to encourage creativity and innovation may find it difficult to be promoted, even though their ideas might be better for the organization in the long run. Fortunately, the competing values framework can be applied at the organization level to assess organization culture (Cameron & Quinn, 2006). Conducting an organizational culture assessment, which we discuss in more detail in Module 3, can be invaluable for managers trying to gain insight into their organizations.

The competing values framework integrates opposites. It is not easy to think about opposites. The failure to understand them, however, can hinder your development as a managerial leader. We will therefore begin by describing in more detail four broad action imperatives that managers face in their organization. We will then turn to the specific competencies that are associated with each action imperative. Finally, we will describe a process for developing each of the competencies at the behavioral level.

The competing values framework is helpful in pointing out some of the values and criteria of effectiveness by which work units and organizations are judged. As noted above, because these values and criteria of effectiveness often appear to call for different types of action by managers, we use the terms Collaborate, Control, Compete, and Create as a shorthand labels to refer to much more complex sets of activities.

Collaborate. The upper left quadrant of the competing values framework, reflecting the values of the human relations model, relates to the Collaborate action imperative (designated by the color yellow). Effectiveness in the collaborate quadrant depends on creating and sustaining commitment and cohesion. Collaborators are expected to encourage open and respectful communication from everyone, which requires first and foremost a deep understanding of and concern for others as well as oneself. Collaborators benefit the organization by mentoring and developing individuals as well as managing groups and leading teams. Perhaps most importantly, collaborators are expected to manage conflict in ways that encourage constructive conflict and discourage destructive conflict. Consider, for example, this description of a public manager who excels at the collaborate action imperative:

It is like any company. The finance people and the operations people are always at war. He brings people like that into a room, hardly says a word, and walks out with support from both sides. Same with subordinates—he brings us together, asks lots of questions, and we leave committed to get the job done. He has a gift for getting people to see the bigger picture, to trust each other, and to cooperate.

Control. The bottom-left quadrant of the competing values framework is associated with the Control action imperative (designated by the color red). Effectiveness in the control quadrant is based on establishing and maintaining stability and continuity. With respect to control, managers are expected to know what is going on in the unit, to determine whether people are complying with the rules, and to see whether the unit is meeting its goals. The complex nature of most organizations also requires that managers be able to work across functions, not just within their own unit. Planning and coordinating projects requires handling data and forms, reviewing and responding to routine information, conducting inspections and tours, and authoring reviews of reports and other documents. Performance must be measured for both efficiency and effectiveness, and feedback must be provided in timely and relevant ways. Managers who excel at control are often recognized for their extensive understanding of the most minute details of the organization, as seen in the following description of one manager.

She has been here for years. Everyone checks with her before doing anything. She is a walking computer. She remembers every detail, and she tracks every transaction that occurs. From agreements made eight years ago, she knows which unit owes equipment to which other unit. Nothing gets past her. She has a sixth sense for when people are trying to hide something.

Compete. The lower-right quadrant represents the Compete action imperative (designated by the color blue). Improving and increasing productivity and profitability is the central criteria of effectiveness for the compete quadrant. This requires that all members of the organization understand the mission of the organization and what they must to do to help achieve that mission. Managers focusing on the Compete action imperative need to have a thorough understanding of the external environment before they can develop an appropriate vision for the organization. To turn that vision into a reality, managers must communicate not only the broad vision but must also clarify expectations for employees through processes such as planning and goal setting, and designing and organizing work. Finally, the effective competitor must translate goals into actions with effective execution. Competing effectively in today's fast-paced environment requires a strong work ethic and the ability to take quick, decisive actions. Managers who excel at competing are expected to be task oriented and work focused. They are characterized as having high interest, motivation, energy, and personal drive. They are supposed to accept responsibility, complete assignments, and maintain high personal productivity. This usually involves motivating members to increase production and to accomplish stated goals. The following description exemplifies a manager who focuses on the compete action imperative:

She is everywhere. It seems as if she never goes home. But it is not just her energy; she is constantly reminding us why we are here. I have worked in a lot of organizations, but I have never been so clear about purpose. I know what I have to do to satisfy her and what the unit has to do. In some units around here, the employees really don't care; she has caused people to care about getting the job done.

Create. Finally, the upper-right quadrant of the framework reflects the values of the open systems model and is labeled Create (designated by the color green). Effectiveness in the create quadrant is evaluated based on the ability to adapt to change and acquire external support. All managers are expected to facilitate adaptation and change, of course, but this core competency is especially relevant in the create quadrant. Paying attention to the changing environment, identifying important trends, and fueling and fostering innovation are fundamental tasks for managers in the create quadrant. In addition, managers must build their power base and negotiate agreement before they can put their ideas into action. Consider, for example, this description:

In a big organization like this, most folks do not want to rock the boat. She is always asking why, looking for new ways to do things. We used to be in an old, run-down wing. Everyone accepted it as a given. It took her two years, but she got us moved. She had a vision, and she sold it up the system. She is always open, and if a change or a new idea makes sense, she will go for it.

As you think about the four action imperatives for managerial leaders described above, you may notice that these descriptions are as applicable to first-level supervisors as they are to executive-level managers of large organizations. The descriptions of the action imperatives are not tied to a particular level of organizational hierarchy or type of organization. Indeed, researchers and consultants have used the competing values framework to structure management education, development, and training programs for first-, middle-, and upper-level managers in a wide variety of public, private, and not-for-profit organizations in the United States as well as internationally (Ban & Faerman, 1988; Faerman, Quinn & Thompson, 1987; Giek & Lees, 1993; Quinn, Sendelbach & Spreitzer, 1991; Sendelbach, 1993).

Managerial responsibilities do, of course, vary across levels of organizational hierarchy. Common sense will tell you that the specific job tasks and responsibilities associated with the first-level manager related to the Create action imperative, for example, will likely be starkly different from those of the upper-level manager focusing on this same action imperative. In some cases, however, while the specific job tasks and responsibilities vary across levels of organizational hierarchy, some of the required competencies will remain the same. For example, all managers need to have good interpersonal skills and to have a high level of self-awareness (Kiechel, 1994). Similarly, all managers need to be able to develop plans and to adapt those plans when circumstances change. In this latter case, however, the scope and time frame of planning will likely differ, as will the steps of the planning process. Thus managers may need to learn different competencies to plan at different levels of the organization.

As managers are promoted from one level of the organization to the next, they need to identify which behaviors associated with the various action imperatives will generally remain the same, as well as which new behaviors need to be learned and which must be unlearned (Faerman & Peters, 1991). They must also understand how to use multiple competencies and perform in behaviorally complex ways as this may change from one managerial position to another. Similarly, human resource managers and those who are mentoring managers as they are promoted need to understand what the similarities and differences in managerial jobs across levels of organizational hierarchy are so that they can help these individuals to grow and develop as they make these transitions (DiPadova & Faerman, 1993).

The managerial competencies covered in this text and shown in Table I.2 reflect both management practice and theory. They are derived from two principle research studies conducted with practicing managers. More than 250 initial competencies were generated by mid-level and senior managers, administrators, union representatives, and scholars (see Faerman, et al. 1987; Lawrence et al., 2009 for details). In terms of theory, when the initial lists of competencies were analyzed, they clustered into four basic categories, consistent with the structure of the competing values framework. Some competencies may be less relevant to you in your current position than others. You may have responsibilities that require competencies that we have not covered but that clearly fit within the theoretical framework. That should not be surprising. In the final analysis, master managers cannot rely on simple checklists for success. Master managers must be able to step back, see the big picture, and then modify their strategies and actions according to the demands of the current situation. The four action imperatives and underlying theoretical models help us to organize our thoughts about what is expected of a person holding a position of leadership. The ultimate goal is for you to be able to integrate a diverse set of competencies that will allow you to operate effectively in a constantly changing world of competing values.

Table I.2. Key Competencies Associated with the Four Quadrants of the Competing Values Framework

Collaborate: Creating and Sustaining Commitment and Cohesion |

Understanding Self and Others |

Communicating Honestly and Effectively |

Mentoring and Developing Others |

Managing Grouns and Leading Teams |

Managing and Encouraging Constructive Conflict |

Control: Establishing and Maintaining Stability and Continuity |

Organizing Information Flows |

Working and Managing Across Functions |

Planning and Coordinating Projects |

Measuring and Monitoring Performance and Quality |

Encouraging and Enabling Compliance |

Compete: Improving Productivity and Increasing Profitability |

Developing and Communicating a Vision |

Setting Goals and Objectives |

Motivating Self and Others |

Designing and Organizing |

Managing Execution and Driving for Results |

Create: Promoting Change and Encouraging Adaptability |

Using Power Ethically and Effectively |

Championing and Selling New Ideas |

Fueling and Fostering Innovation |

Negotiating Agreement and Commitment |

Implementing and Sustaining Change |

A competency suggests both the possession of knowledge and the behavioral capacity to act appropriately using that knowledge. To develop competencies, you must both be introduced to knowledge and have the opportunity to practice your skills. Many textbooks and classroom lecture methods provide the knowledge but not the opportunity to develop behavioral skills and to reflect on the use of those skills.

In this book, we will provide you with both. The structure we will use is based on a five-step model developed by organizational scholars Kim Cameron and David Whetten. Rather than focusing on learning from a simple instructional approach of an expert giving a lecture, Whetten and Cameron (2010) recommend an instructional-developmental approach that includes an expert giving a lecture plus students experimenting with new behaviors. Each of the competencies covered in the text includes the five-steps of the ALAPA model, as described below.

Step 1: Assessment | Helps you discover your present level of ability in and awareness of the competency. Any number of tools, such as questionnaires, role-plays, or group discussions, might be used. In this text, we generally use brief questionnaires. |

Step 2: Learning | Involves reading and presenting information about the topic using traditional tools, such as lectures and printed material. Here we present information from relevant research and suggest guidelines for practice. |

Step 3: Analysis | Explores appropriate and inappropriate behaviors by examining how others behave in a given situation. We will use cases, role-plays, or other examples of behavior. Your professor may also provide examples from popular movies, television shows, or novels for you to analyze. |

Step 4: Practice | Allows you to apply the competency to a work-like situation while in the classroom. It is an opportunity for experimentation and feedback. Again, exercises, simulations, and role-plays will be used. |

Step 5: Application | Gives you the opportunity to transfer the process to real-life situations. Usually assignments are made to facilitate short- and long-term experimentation. |

When initially exposed to these components, students respond in different ways. Some appreciate the structure and invest themselves in the complete learning process. Others may feel that the Assessment exercises are unnecessary; they want to jump directly into the Learning. Still others may think that a particular Practice or Application activity isn't relevant to their current job or career aspirations. Although no textbook can perfectly meet the expectations and needs of every student, we have found that most students only fully appreciate the benefits of the activities after they have invested time in them. For example, after completing an exercise on assumptions about performance evaluations, one MBA student wrote, "I never realized my thoughts on performance evaluation until this exercise. [It] gave me thoughts about how I could change this process at my work." This type of reaction emphasizes the importance of reflection throughout the learning process. Reflection helps us move to a higher level of understanding. Research suggests that reflection can greatly enhance awareness of the impact of self-directed learning (Rhee, 2003) and improve skill development (Argyris, 2002). To encourage reflection, we include a brief comment after most of the exercises throughout the text.

In working with the ALAPA model, we discovered that the five components, and the methods normally associated with each component, need not be implemented separately. A lecture, for example, does not need to follow an assessment exercise and precede an analysis exercise; a lecture might be appropriately combined with a role-play in some other step. The methods can be varied and even combined in the effective teaching and learning of a given competency.

The next section uses the ALAPA model to introduce a competency that all students can immediately put into practice: Thinking Critically.

This assessment exercise has two parts. Please complete part 1 before moving to part 2.

Directions Part 1 | Think of a topic or issue or situation that you find very upsetting or frustrating. Do a little "ranting" on that issue. That is write some very strong and emotional statements about this issue or situation. You might begin with "One thing that makes me furious is__________. "Try to write four or five sentences. |

Part 2 | Now imagine that you need to "go public" with your feelings and opinions and convince someone else to share at least some of the intensity you feel about this issue. Is there anything in your ranting that you might convert into an argument a line of reasoning that another person might find legitimate? Read and discuss your sentences with a classmate. Talk about why you feel that some of your statements are not good raw material for public reasoning but others might be. |

Organizations want people who can "go public" with their ideas and reactions, quickly and concisely. When you have casual conversations with your friends, you don't always have to support your opinions with evidence. You can just express an opinion. But in the workplace you have to support your claims and proposals in a more systematic and concise way. It's one thing to say that you like the color blue; it's quite another to say that you prefer one brand of cell phone over another. In the first case you are simply expressing a preference whose grounds are wholly personal. Another person can "argue" that green is the best color, but the argument cannot be resolved by recourse to external issues. The preferences here are purely and completely personal.

However, in the second example, in which you state that you prefer this cell phone over another, the grounds for the claim you are making do not depend completely on your own taste. There are external factors you can discuss with another party. There are criteria of design, cost, convenience, and so forth that can be put on the table—"I like the smaller size and lighter weight of the Nokia phone; the user interface on the Nokia makes messages easier to read; the menu has fewer steps for manipulating the functions I use most often; the sound quality is better." True, some of these are personally experienced, but they are criteria that go beyond personal taste. They are shareable, and in some cases impersonal (cost, for example), grounds for having a preference or making a recommendation.

In this section, we examine the skill of thinking critically, which is the first step in formulating clear and compelling arguments. Developing critical thinking skills will improve the quality of your evaluations and increase the credibility of your recommendations.

Let's think for a moment about thinking itself as a learned human activity. In what ways has your formal education helped you to "think" more effectively? We're not asking about specific knowledge you've accumulated, but how your ability to handle ideas and marshal evidence has improved. Another way to pose the question is, "How has your formal education helped you to understand the events that you observe and the information you encounter in daily life?" We have asked this question of many MBA students. Here are some of the responses we have found most interesting and helpful.

My education has helped me "complexify" my thinking. I have learned that there are seldom simple, single causes for events. There are usually complex, multiple causes that drive events. As an undergraduate, I majored in history. I wrote my senior research paper on the causes of World War I. I can't tell you in one sentence what caused that war; but I can tell you what the contributing conditions were and what "trigger events" led to the outbreak of the war. That's what I mean by complex thinking rather than simple, black-and-white thinking.

Some of the tools I've gained from school have helped me approach things in a more systematic way. For example, my study of statistics has really helped me separate the single dramatic cases, the N of 1 examples, from patterns of events. The other day, as part of preparing to write a paper on healthcare policy, I watched a person on the C-Span TV network who was testifying before a congressional committee about the quality of healthcare. This person, who couldn't get some important surgery paid for by his HMO (health maintenance organization), had a heartrending story to tell. But I wanted to know how representative this example was. How many people have been in this situation? Is it a one-of-a-kind case, or is it typical? So often, the most dramatic data crowds out the more valid, less dramatic data.

I am a lot better at asking precise questions than I was before I went to college. Even in casual conversation with people, I can learn a lot more and contribute more to a conversation by asking good questions. When someone makes a statement like "I thought that movie was really lame," I follow up with a question like, "What makes you say that?" When someone says, "This book was stupid," I want to ask a question like "Was everything in the book stupid, or just part of it?" Sometimes people think I'm weird, but most of the time my questions make the conversations go better.

The students quoted above all realize that issues are often more complex than they at first appear, that the "facts" needed to make a rational decision are not always available to us, and that people often make decisions based on very thin or limited information. They also seem to understand that different people will not always agree on what a "fact" is in a particular case—or perhaps not agree on the meaning or significance of that fact.

The kind of attitude these students demonstrate is appropriate to the role of the manager. Managers spend a lot of time both presenting evidence to support their own ideas and evaluating evidence presented by others. Effective managers are effective thinkers. They don't have to be brilliant, but they need to approach evidence and data with both openness and some healthy skepticism.

When reasons are put together and presented to one or more people, they form an argument. We are using the term "argument" to mean a train of reasoning, not a quarrel or a disagreement you have with another person. An argument, in this sense, is a case we make for doing, or believing, or recommending something.

Effective managers are good at both framing their own arguments and reacting to the arguments of others. At any given moment, your task as a manager may be to react to someone else's recommendation or to make your own recommendation for doing something. For example, you might make the following suggestion at a weekly staff meeting: "We need to adopt this software application for tracking our financial data because . . ." What comes after that "because" is the support or the gist of your argument. Without that support, your suggestion or proposal would probably not carry much weight. Now, note that reasoning, or critical thinking, as we are describing it, is primarily a process not of creating ideas but of presenting and evaluating ideas and information. The task of the critical thinker is to make the best decision with the available information in a particular circumstance. The better you are at presenting your own cases and analyzing the cases others put in front of you, the more effective a leader you will be. We're now going to present some tools for mapping arguments and examining evidence clearly and efficiently. This approach to mapping arguments is based on An Introduction to Reasoning (Toulmin, Rieke, and Janik, 1984, pp. 1–59), which notes that most arguments, whether simple or complex, have three elements:

The claim or conclusion of the argument. The claim answers the question, "What's the point here?"

The grounds, or the facts and evidence that support the claim. The claim can be no stronger than the grounds that support it. The grounds answer the question, "What do you have to go on?" or "What leads you to say that?"

The warrant, or the bridge between the claim and the grounds. Sometimes this bridge is obvious; sometimes not. The warrant or bridge answers the question, "How does your claim connect to the grounds you've offered" (Toulmin et al., 1984, pp. 30—38). The warrant is the most subtle of the three elements of argumentation, but if you develop an understanding of it, it will prove a powerful tool for both creating and evaluating arguments.

The following example demonstrates how an implied warrant can be used. The argument is simple because only the claim and grounds are indicated:

I see smoke; there must be fire.

The claim here is "there must be fire." The grounds or evidence on which the claim is based is "I see smoke." Another way to say this is "I see smoke, so there must be fire." But the warrant or bridge that makes the connection between the claim and the evidence is not stated. The warrant is, of course, "where there's smoke there's usually fire." (Notice that the warrant has a qualifier to it: the word "usually." Sometimes there is smoke without fire.)

Now, examine the following train of reasoning. The elements in this argument are scrambled. Some of the statements below regarding a patient who was admitted to a hospital emergency room (ER) are warrants; some are grounds; one is a claim. All the other statements revolve around that claim. For each statement, indicate whether you think it is a claim, a ground, or a warrant.

_____ The patient complains of nausea, which has lasted for over 24 hours.

_____ The patient's examination shows pain and tenderness in his lowerright abdomen.

_____ The patient has a temperature of 101°.

_____ Appendicitis is often triggered by a viral flu infecting the gastrointesti-nal tract.

_____ The patient's pain has migrated over the past 48 hours from the center of the belly to the lower-right abdomen.

_____ The pain associated with acute appendicitis often "migrates" from the left side, or the midsection, to the lower-right abdomen.

_____ The patient is most likely suffering from acute appendicitis and should be X-rayed and prepared for surgery.

_____ The patient's history shows a bad case of viral flu within the past two weeks.

Notice that the warrants are the items that create a bridge between a factual observation and the one claim or recommended action in the list. In the list above there happens to be only one claim. Everything else is either a ground or a warrant. When experts communicate among themselves, they often leave out the warrants behind their reasoning because the warrants are understood. But when they talk to a nonexpert, they need to be more explicit. That means they have to spell out the warrants that connect the claims they are making to the grounds used to support those claims.

For example, a medical intern who had just examined the patient described above might say to the attending physician in the ER,

The patient has a temperature of 101, nausea for the past several hours, migrating pain and tenderness now settled in the lower-right abdomen. The patient says he has also had a recent case of viral stomach flu. I recommend we prep him for surgery on his appendix.

The attending physician might say, "Fine, sounds like an inflamed appendix to me." The warrants, all taken from clinical research, are already understood. But often we need to make our warrants explicit. As our colleague Allen Bluedorn says when teaching this model of reasoning, you need to "show your work" as you do on a calculus homework problem or a chemistry exam. If the attending physician wants to test the logic of the intern's diagnosis, he might ask a question such as, "How does the patient's recent case of the flu support your diagnosis?" The intern would then say that clinical research shows that a viral flu is often the triggering event in causing a person's appendix to become infected. The questions asked by the attending physician require the intern to show her work.

In argumentation, you show your work when you expose the bridges or warrants between the evidence you're presenting and the claim(s) that your evidence supports. When people have difficulty following our train of reasoning, the problem is often caused by our failure to make our warrants explicit.

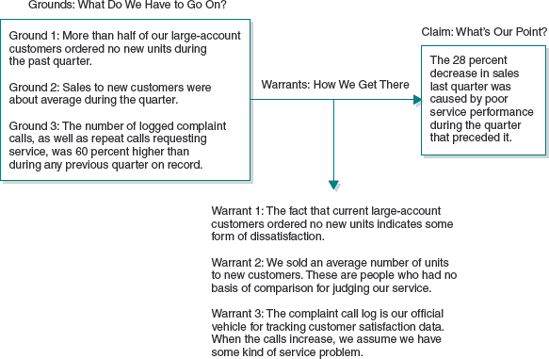

Let's see how we can use this model of argumentation to map some arguments that managers encounter in reports or meetings. Here's an example from a report by a sales manager in a manufacturing company.

We conclude that the 28 percent decrease in unit sales for this quarter was caused by a dramatic deterioration in the quality of service provided during the previous quarter.

The strongest evidence that poor service is the cause of the lower sales is the fact that more than half of our large, regular accounts ordered no new units during the quarter. These are the customers who have a history with our service—some benchmarks for tracking how our service stacks up over time. Now, they apparently have a reason to be dissatisfied and feel that service quality had declined.

On the other hand, sales to new accounts were about average during this quarter. These are customers who have had little experience with the quality of our service work. Further, we suspect that the quality of our service has dropped sharply, because the number of complaint calls recorded in the log, as well as repeat calls requesting service, is about 60 percent higher than during any other quarter on record.

This argument is pretty straightforward:

The claim is that a 28 percent decrease in sales last quarter was caused by poor service performance during the quarter that preceded it.

The grounds or evidence that the quality of service declined in the previous quarter is threefold.

Ground 1: More than half of our large-account customers ordered no new units during the past quarter.

Ground 2: Sales to new customers were about average during the quarter.

Ground 3: The number of logged complaint calls, as well as repeat calls requesting service, was 60 percent higher than during any previous quarter on record.

The warrants, or bridges, that tie the data and claim together are also threefold.

Warrant 1: The fact that current, large-account customers ordered no new units indicates some form of dissatisfaction.

Warrant 2: We sold an average number of units to new customers. These are people who had no basis of comparison for judging our service.

Warrant 3: The complaint call log is our official vehicle for tracking customer satisfaction data. When the calls increase, we assume we have some kind of service problem.

Notice how the author of the report supports his statement that the quality of service has "dramatically deteriorated." He alludes to an official piece of evidence, the service department's log book. Notice that while there is only one major claim, there are several grounds, or pieces of evidence, supporting the claim and a matching number of warrants connecting each ground to the claim. We can draw or map this argument as shown in Figure I.3.

As you work through the exercises in the rest of this text, apply what you have learned about claims, grounds, and warrants. For example, when assessing whether you are a team player (Module 1), recognize that your assessment is simply a claim—what grounds do you have to support that claim? By pushing yourself to provide, not just claims, but also grounds and warrants in the exercises throughout this text, you will continue to develop your critical thinking skills. This practice will also be valuable for improving related competencies such as communicating honestly and effectively (Module 1) and negotiating agreement and commitment (Module 4).

Objective | This exercise will give you more experience at analyzing arguments. | ||||||||||||||||||

Directions | The following exercise includes two arguments on the same topic. Your job is to read these arguments and analyze them in terms of their plausibility, validity, and persuasiveness.[a] This can be a group exercise or an individual task. If your instructor prefers to have you work as a group, here are guidelines for the process. | ||||||||||||||||||

Group Task | Break into groups of four. Two people should analyze one argument together, and the other two people should analyze the other argument together. Take 15 minutes to read and discuss the arguments, and then present your analysis to the other pair of classmates. Evaluate the arguments using the 7-point scale and the evaluation criteria below. | ||||||||||||||||||

Scale | Terrible 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Excellent

| ||||||||||||||||||

[a] From R. Petty and J. T. Cacioppo, Communication and Persuasion: Central and Peripheral Routes to Attitude Change. (New York: Spring-Verlag New York Inc., 1986), 54–55, 57–58. Used with permission. We wish to thank Allen Bluedorn of the University of Missouri for suggesting this exercise and for his helpful advice on teaching critical thinking. | |||||||||||||||||||

Argument 1

The National Scholarship Achievement Board recently revealed the results of a five-year study on the effectiveness of comprehensive exams at Duke University. The results of the study showed that since the comprehensive exam has been introduced at Duke, the grade point average of undergraduates has increased by 31 percent. At comparable schools without the exams, grades increased by only 8 percent over the same period. The prospect of a comprehensive exam clearly seems to be effective in challenging students to work harder and faculty to teach more effectively. It is likely that the benefits observed at Duke University could also be observed at other universities that adopt the exam policy.

Graduate schools and law and medical schools are beginning to show clear and significant preferences for students who received their undergraduate degrees from institutions with comprehensive exams. As the dean of the Harvard Business School said, "Although Harvard has not and will not discriminate on the basis of race or sex, we do show a strong preference for applicants who have demonstrated their expertise in an area of study by passing a comprehensive exam at the undergraduate level." Admissions officers of law, medical, and graduate schools have also endorsed the comprehensive exam policy and indicated that students at schools without the exams would be at a significant disadvantage in the very near future. Thus, the institution of comprehensive exams will be an aid to those who seek admission to graduate and professional schools after graduation.

Argument 2

The National Scholarship Achievement Board recently revealed the results of a study they conducted on the effectiveness of comprehensive exams at Duke University. One major finding was that student anxiety had increased by 31 percent. At comparable schools without the exam, anxiety increased by only 8 percent. The board reasoned that anxiety over the exams, or fear of failure, would motivate students to study more in their courses while they were taking them. It is likely that this increase in anxiety observed at Duke University would also be observed and be of benefit at other universities that adopt the exam policy.

A member of the board of directors has stated publicly that his brother had to take a comprehensive exam while in college and is now a manager of a large restaurant. He indicated that he realized the value of the exams, since his father was a migrant worker who didn't even finish high school. He also indicated that the university has received several letters from parents in support of the exam. In fact, four of the six parents who wrote in thought that the exams were an excellent idea. Also, the prestigious National Accrediting Board of Higher Education seeks input from parents as well as students, faculty, and administrators when evaluating a university. Since most parents contribute financially to their child's education and also favor the exams, the university should institute them. This would show that the university is willing to listen to and follow the parents' wishes over those of students and faculty, who may simply fear the work involved in comprehensive exams.

Reflection | The way that information is presented can have a significant impact on how that information is perceived. When crafting persuasive arguments, having solid grounds and warrants to substantiate your claim may not be enough if you are unable to convey your thoughts in a clear, compelling way. |

Objective | As we noted earlier, warrants connect your grounds to your claims and are often the most difficult part to establish when you first begin develop your argumentation skills. |

Directions | In groups of three to five people, practice supplying the warrant for each set of claims and grounds listed in the table below. More than one plausible warrant can be given for each set. There is no one, perfectly worded answer. The idea is to provide a bridging statement between the claim being made and the grounds provided to support that claim. |

Reflection | When listening to the claims made by others, it can be very helpful to apply what you have learned about argumentation. Sometimes, positions that sound reasonable when we first hear them, fail to hold up once we analyze them more carefully. |

Claims | Grounds | Warrant(s) |

|---|---|---|

Southwest Airlines will have a profitable year next year. | The nation's economic growth is predicted to continue at an annual rate of at least 3 percent over the next year. Southwest has enjoyed greater profits than any airline in North America for the past three years. | |