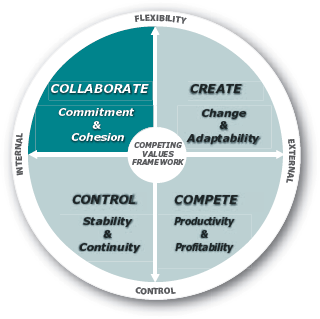

In this first module, we look at the human relations model, which focuses on commitment and cohesion. In building commitment and cohesion, we emphasize an internal focus and flexibility. That is, we are concerned about individuals and groups within the organization and the need to allow for flexibility in order to help employees grow and develop. When employees have opportunities to develop their skills and abilities, they can contribute more effectively to the organization's performance needs.

Organizational Goals. The human relations model has as its primary goal developing committed and involved organizational members. Here we assume that the best way to develop committed and involved members is to give them an opportunity to be involved in organizational processes. In order for employees to be involved, managerial leaders need to help employees see how their work fits into the work unit. Managers must also provide employees with feedback on how well they are performing. In addition, managers need to balance the needs of individuals with the needs of the work unit and to build cohesion among employees, while encouraging employees to express their individuality.

Paradoxes. In the Introduction to this text, we noted that paradoxes exist when two seemingly inconsistent or contradictory ideas are actually both true and that the competing values framework recognizes that managerial leaders are consistently faced with paradoxical situations. Some of these paradoxes emerge from competing demands that result from competing values across quadrants. For example, as we learn about the human relations quadrant, we are, by definition, highlighting aspects of the organization that emphasize flexibility and an internal focus. An overemphasis on internal aspects of the organization, however, can lead managers and employees to lose sight of the fact that the purpose of work organizations is to produce a product or deliver a service to external customers. Similarly, an overemphasis on flexibility can lead managers and employees to forget the value of maintaining stability and continuity in an organization.

In this module, we focus more on paradoxes that emerge from expectations within the human relations quadrant. As you examine each of the competencies, you will see that overemphasis on a particular value can actually lead to poor performance. For example, we believe that one of the most important competencies of a managerial leader is understanding oneself. Increasing one's self-awareness, however, should be understood as a starting point for developing one's capacity for personal growth and development, rather than as an end in itself. Thus, a paradox associated with learning more about yourself is that you increase your capacity to change and become someone new. A second paradox associated with the human relations quadrant emerges when there is an overemphasis on building commitment and cohesion by involving people in decision-making processes. Anyone who has ever been involved in a learning group, however, knows that groups do not always make the best or most efficient decisions. And when employees have opportunities to participate in decision-making processes, it virtually always takes longer than having one person make the decision. We thus need to be careful about not overusing work groups when a quality decision could be made by an individual. Finally, a paradox emerges from the fact that it takes time to develop any skill or ability. Thus, in trying to build the team's capacity in the long run, managerial leaders need to recognize that in the short term the team will be less effective and/or less efficient as individuals are given the opportunity to learn new tasks. As you work through this module and attempt to develop your competencies, keep in mind that effective performance will require you to transcend these paradoxes.

Competencies. The competencies associated with the Collaborate quadrant focus on how managerial leaders can be more effective in their interactions with others. We begin this module by emphasizing what some would argue is one of the most important competencies a managerial leader can possess—understanding self and others. To be effective, a managerial leader must be able to inspire others to action and so must have an understanding of how she is seen by others. Managerial leaders must also be able to monitor how they react to situations and determine the basis for this reaction. By developing this type of self-awareness, managerial leaders also develop their capacity to understand others in their organization. Our next two competencies, communicating honestly and effectively and mentoring and developing employees, focus on interactions with individuals and introduce some important ideas about effective communication that are useful not only in the workplace, but also in your relationships outside the workplace. We then address key issues associated with managing groups and leading teams. Working on effective teams can be an incredibly energizing experience, but ineffective teams can destroy motivation and jeopardize organizational success. Our last competency, managing and encouraging creative conflict, can be applied at both the individual and the group level and challenges the idea that conflict in organizations is bad and should always be avoided.

Unlike professionals who are only responsible for their own work, managerial leaders are responsible for bringing together the work of a number of people and creating a cohesive work unit. Being effective as a managerial leader thus not only requires individuals to be aware of their own strengths and weaknesses in terms of the specific work performed in the unit, but also to be aware of their work style and how they interact with others. It also requires individuals to become more aware that although all members of a work group have something in common, each individual is also in some way unique. Managerial leaders must learn about each employee's abilities, understand how employees' work styles may differ, and consider how each person contributes to the work of the unit and the organization as a whole. Managerial leaders must also consider how employees differ in their feelings, needs, and concerns. People react differently to different situations, and it is important for managerial leaders to be able to perceive and understand these reactions.

As a manager, you need to understand both the commonalities and differences among employees as a first step to understanding how people relate to one another in various situations. By being aware, you can better understand your own reaction to people and their reactions to each other. In the past two decades, many companies have begun to focus on helping managers develop their emotional and social intelligence (Goleman, 1995, 1998; Goleman, Boyatzis & McKee, 2002; Seal, Boyatzis & Bailey, 2006), which involves both intrapersonal competence (how we manage ourselves) and interpersonal or social competence (how we handle relationships). Research in this area has shown that emotional and social intelligence plays a particularly crucial role at higher levels of the organization, where managers spend the vast majority of their day interacting with others.

We begin this section with a focus on understanding yourself, sometimes referred to as self-awareness. The importance of having a good understanding of yourself and what motivates or influences your behaviors should be obvious. If you do not understand yourself, it is nearly impossible to understand others. Yet people often find it difficult to learn about themselves. One reason that people find it difficult to learn about themselves is because their friends and colleagues fear being honest because they think such honesty will create conflict or embarrass the other person. Jerry Hirshberg, founder of Nissan Design International, Inc., notes that people "have mixed feelings about hearing the truth." He states, "It's like a chemical reaction: Your face goes red, your temperature rises, you want to strike back." He labels this reaction "defending and debating" and argues that people need to fight back the tendency to defend and debate by "listening and learning" (Muoio, 1998).

While it may be difficult to receive negative feedback, there is strong evidence that managers with higher levels of self-awareness are more likely to advance in their organizations than those with low self-awareness (Dulewicz & Higgs, 2000). There are, of course, many different dimensions of yourself that you could learn about. For example, Peter Drucker (1999), one of world's foremost authorities on management and leadership, argues that in today's economy, people must be aware of their strengths, their values, and how they best perform. Robert Staub, cofounder and president of Staub-Peterson Leadership Consultants, asserts that "the golden rule of effective leadership [is]: Don't fly blind! Know where you stand with regard to the perceptions of others" (Staub, 1997, p. 170).

Goleman and colleagues' (2000; Goleman, Boyatzis & McKee, 2002) work on emotional and social intelligence identifies self-awareness and self-management as the two key dimensions of emotional intelligence. Within self-awareness, there are three subdimensions: emotional awareness, self-assessment, and self-confidence. Emotional awareness involves recognizing your emotions and how they affect you and others. Individuals who have emotional awareness know what they are feeling and why, and they also understand the connection between their feelings and their actions. Self-assessment involves knowing your strengths and limits and being open to feedback that can help you to develop. Individuals who develop this competence are able to learn from experience and value self-development and continuous learning. Self-confidence refers to an awareness of one's self-worth and capabilities. Individuals who possess self-confidence present themselves with a strong sense of self and are willing to stand up for what they believe in, even if their perspective is unpopular.

In addition to knowing about your emotions, your strengths and limits, and how others perceive you, it is important to know what motivates your behaviors—what influences how you will react in different situations. One major influence on your behavior is your personality. While no one always reacts in the same way under all circumstances, people do have a tendency to act and react to situations with some level of consistency. An individual's personality is generally described in terms of those relatively permanent psychological and behavioral attributes that distinguish that individual from others. The notion that personality is relatively permanent stems from the idea that personality is a trait that can change in adulthood but is mostly formed in childhood and adolescence. Thus, "individuals can be characterized in terms of relatively enduring patterns of thoughts, feelings, and actions . . . [that] show some degree of cross-situational consistency" (McCrae & Costa, 2008, p. 160). The concept of personality can thus be used to differentiate among individuals as well as to describe similarities among people with similar personality traits.

While there are many different approaches to understanding personality, two of these approaches stand out as being the most widely used in research and in organizational training and development seminars on individual differences in organizations. The first, the Five-Factor Model, is generally seen by psychologists as the most widely accepted taxonomy for studying personality (John, Naumann & Soto, 2008). The second, the Myers-Briggs Type Inventory, is based on the work of Carl Jung and is more popular in organizations for understanding differences in employee' work styles.

As the name would imply, the Five-Factor Model presents five factors, or basic tendencies, that researchers argue encompass most of what has been described as personality (McCrae & Costa, 2008). In the model, each factor is named for one of two ends of a continuum. Of course, most individuals do not fall at the ends of the con-tinua, although people are likely to have a tendency toward one end or the other. As you read the description of each of the traits, you might try to place yourself on each of the continua.

The first factor is referred to as neuroticism. Individuals who score high on this dimension tend to worry a lot and are often anxious, insecure, and emotional. Alternatively, those who score low tend to be calm, relaxed, and self-confident. The second factor, extraversion, has also been referred to as urgency and assertiveness. This factor assesses the degree to which individuals are sociable, talkative, and gregarious in their interactions with others versus reserved, quiet, and sometimes even withdrawn and aloof. The third factor, openness, also sometimes called intellectance, focuses on the degree to which an individual is proactive in seeking out new experiences. Individuals who score high on this measure tend to be curious, imaginative, creative, and nontradi-tional. Those who score low tend to be more conventional, concrete, and practical. Agreeableness, the fourth factor, focuses on the degree to which individuals are good-natured, trusting of others, and forgiving of others' mistakes, as opposed to cynical, suspicious of others, and antagonistic. Finally, conscientiousness is associated with individuals' degree of organization and persistence. Those who score high on this continuum tend to be more organized, responsible, and self-disciplined; those who score low tend to be more impulsive, careless, and perceived by others as undependable.

Interestingly, researchers have found inconsistent relationships between the five factors and various aspects of leadership. For example, some researchers found extraver-sion and agreeableness to be positively related, and neuroticism negatively related, to some aspects of leadership, particularly emergent leadership in a leaderless group, suggesting that when a group is formed with no explicit leader, the individual who is more extraverted, agreeable, and emotionally stable will likely emerge as the informal leader (Hogan, Curphy & Hogan, 1994). Other researchers have found conscientiousness to be the strongest predictor of leadership performance (Strang & Kuhnert, 2009). Regardless of which personality factors predict leadership performance, it is important for managerial leaders to be aware of their tendencies as they perform their work.

The Myers-Briggs Type Inventory (MBTI) is one of several personality assessment instruments based on Carl Jung's theory of psychological types. Jung noticed that people behaved in somewhat predictable patterns, which he labeled types. He noted that types could be described along three dimensions: introversion—extraversion, sensing-intuition, and thinking—feeling. Later, Katharine Briggs and her daughter, Isabel Briggs Myers, added a fourth dimension: judging—perceiving (Keirsey, 1998). Their assessment instrument is widely used in organizational workshops to help people understand the different work styles of people in a work unit.

The first dimension, introversion—extraversion, is similar to the Five-Factor Model's extraversion factor. It focuses on the degree to which individuals tend to look inward or outward for ideas about decisions and actions. Individuals who are introverted tend to be reflective and value privacy. Individuals who are extraverted tend to like variety and action, and are energized by being with people. The second dimension, sensing—intuition, focuses on what we pay attention to when we gather data. Individuals who are sensing types tend to focus on facts and details; they absorb information in a concrete, literal fashion. Intuitive types, on the other hand, tend to try to see the big picture and focus more on abstract ideas.

While sensing—intuition focuses on how we gather data, thinking—feeling focuses on how we use information when making decisions. Thinking types tend to decide with their brains, whereas feeling types tend to decide with their hearts. Thinking types use analytical and objective approaches to decision-making. Feeling types tend to base decisions on more subjective criteria, taking into account individual differences. The final dimension, judging-perceiving, focuses on approaches to life and thinking styles. Judging types are task oriented and they tend to prefer closure on issues. They are good at planning and organizing. Perceptive types are more spontaneous and flexible, and they tend to be more comfortable with ambiguity.

Because the underlying management models of the competing values framework reflect different assumptions about how decisions should be made, some organizational scholars have suggested that certain personality types may be more inclined toward some approaches to management than others. For example, individuals who score high on thinking are likely to prefer the rational approach to decision-making based on goals and objectives that is the hallmark of the rational goal quadrant. In contrast, individuals who score high on feeling are likely to be more comfortable with the human relations quadrant approach, which calls for more participative approaches. With respect to the data-gathering dimension, sensing types who want to see the facts and figures are likely to fit well in the internal process quadrant with its emphasis on measurement and control. Conversely, intuitive types who are more interested in the big picture may be more comfortable with the open systems approach, which argues for paying attention to what is going on outside the organization.

The four dimensions of the MBTI can be combined to create different combinations, such as extraverted—sensing—thinking—judging or introverted—sensing—feeling— judging. When you combine all four dimensions, there are 16 different personality types that can be identified. Workshops that focus on people's work styles tend to focus on the combinations because they can help people understand why people approach work tasks in different ways. You might think back to a situation where some people in the group jumped right into the task while others wanted to analyze the nature of the problem first. Puccio, Murdock, and Mance (2007) describe these differences as psychological diversity, which they define as "differences in how people organize and process information as an expression of their cognitive styles and personality traits" (p. 205). They argue that this type of diversity can have profound effects on the workplace and note that leaders who understand this type of diversity "are in a much better position to leverage their strengths and to find ways to compensate for their deficiencies" (Puccio et al., 2007, p. 205).

As noted above, research has shown that managers with higher levels of self-awareness are more likely to advance in their organizations. It is not, however, simply important to increase your self-awareness. Rather, effective managerial leaders use their self-awareness to identify areas of potential growth, that is, areas where they can become more effective. Seal, Boyatzis, and Bailey (2006) describe a process called "intentional change theory," whereby individuals can identify desirable, sustainable changes they would like to make by asking themselves a series of questions, starting with "Who do I want to be?" (p. 201). The answer to this question gives individuals a sense of their "ideal self." By then asking questions about how one's current strengths and weaknesses (real self) differ from one's ideal self, individuals can create an action plan, or what they label as one's "learning agenda."

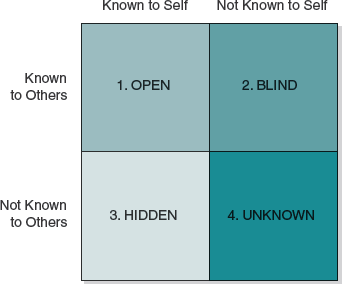

In the Assessment exercise, you had the opportunity to use self-reflection, as well as feedback from a partner to help you learn about yourself (real self). Here we present a simple but helpful framework that can help you to develop a more realistic picture of your real self. The framework was developed by Joseph Luft and Harry Ingham (1955), who named it after themselves, calling it the Johari window. As shown in Figure M1.1, it has four quadrants. In the upper left is the Open area, which represents the aspects of who you are that are known both to yourself and to others with whom you interact. In the upper right is the Blind area. Here are the aspects of you that others see but you do not recognize. In the lower left is the Hidden quadrant, sometimes referred to as the façade. These are the things that you know but do not reveal to others. Finally, in the lower right is the Unknown quadrant. Here are those aspects of who you are that neither you nor others are yet aware of; they exist but have not been directly observed, and neither you nor those with whom you interact are aware of their impact on the relationship. When they are discovered, often through deep self-reflection, their impact becomes an important place for personal growth.

The sizes of the four quadrants change over time. In a new relationship, the Open quadrant is small. As communication increases, it grows large and the Hidden quadrant begins to shrink. With growing trust, we feel less need to hide the things we value, feel, and know. It takes longer for the Blind quadrant to shrink in size because it requires openness to honest feedback. Not surprisingly, the Unknown quadrant tends to change most slowly of all because it requires people to be introspective and to explore things about themselves that are generally taken for granted. While it is can be a very large quadrant that greatly influences what we do, many people totally close off the possibility of learning about the Unknown quadrant.

As noted above, people sometimes use a great deal of energy in order to hide, deny, or avoid learning about themselves, particularly their inconsistencies and hypocrisies. When colleagues and employees sense that you are not open to feedback, they will avoid sharing important information with you. As a result, the Open quadrant begins to shrink, and the others begin to enlarge. When the Open quadrant increases in size, however, the others shrink. As a result, more energy, skills, and resources can be directed toward personal growth and development and the tasks around which the relationship is formed. This leads to more openness, trust, and learning, and positive outcomes begin to multiply. One way for you to show others that you are open to feedback is to systematically share information about yourself. Ben Dattner (2008) urges managers to provide their employees with a "Managerial User's Manual." He notes that the more you can tell your employees about what you value, what motivates you, and how you work, the more likely it is that you can create an open dialogue about how to work together. He also suggests that the manual should be an evolving document, and that managers should actively solicit input from colleagues and employees about the accuracy and usefulness of the manual. Table M1.1 provides some basic guidelines that can help you increase the size of your Open quadrant by asking for feedback.

Table M1.1. Guidelines for Asking for Feedback

|

|

|

|

|

The second two dimensions of emotional and social intelligence are social awareness and relationship management. Within the area of social awareness, the three subdimen-sions are empathy, organizational awareness, and service orientation. Empathy lies at the heart of understanding others. It involves "sensing others' emotions, understanding their perspective, and taking active interest in their concerns" (Goleman, Boyatzis & McKee, 2002). Leaders who are able to show empathy are able to put themselves in the position of others and see the world as others see it. While employees may not always agree with managers' decisions, they are more likely to trust managers who demonstrate an understanding of their reactions to organizational decisions.

One difficult part of practicing empathy is that some people are uncomfortable with expressing negative emotions in the workplace. That is, they believe that it is unprofessional to express fear, sadness, or anger in the work setting. The fact is, however, that individuals do react emotionally to situations, and the better a leader is at reading people's emotions, the more effective the leader will be at helping to resolve difficult issues and maintaining a more cohesive work environment.

What then can managers do to demonstrate more empathy? What steps can they take to help employees feel that managers are truly interested in their ideas and opinions, even if the final decision is not the one the employee would make? First, it is important to begin practicing empathy before there is a difficult situation. That is, keep in mind that empathy is more than understanding people's emotions; it also involves understanding those individuals' perspectives and concerns. Here, it is helpful to recall the quadrants of the Johari window and to remember that others also have Blind, Hidden, and Unknown areas. Managers who appreciate that employees and colleagues also have these three covert areas and are likely be defensive about them, can begin by encouraging those individuals to move information from the Hidden quadrant to the Open quadrant. That is, in the same way that trust increases when you provide others with a user's manual to help them learn more about you, you might encourage your employees (and colleagues) to also develop a user's manual in which they tell you about what they value, what motivates them, and how they work best. Of course, managers need to be sensitive and respectful of others' need for privacy and to recognize that their first reaction may be defensiveness. If, however, managers provide a role model of sensitivity, openness, and willingness to learn, and ask others for feedback, it is more likely that employees with reciprocate with the same.

Table M1.2. Empathic Listening: Feeling the Experience of Others

1.Emptying Oneself: Before you can engage in empathic listening, you must move away from your own problems and concerns. While your personal problems and concerns may be important to you, when you are engaging in empathic listening, you must remember that you need to focus on the other person's problems and concerns. |

2.Paying Attention: Listen carefully to what the person is saying, and remember that communication is more than words. What is behind the words? Are the words that are being expressed congruent with the individual's nonverbal signals? You can use reflective listening (see Competency 2 in this module) to see if there are things the individual is not saying. |

3.Accepting the Other Persons Reaction: Remember that you are accepting this reaction as the other person's reaction. You do not need to agree with this reaction; you simply need to assure the other person that you accept that this is how he understands the situation. Listen carefully for the feelings beneath the statement. |

4.Avoiding Judgment or Comparison: Once you have accepted the other person's reaction as valid, avoid comparing this reaction to your own or to other individuals' reactions. Do not try to suggest that the person should see this in another way or try to provide "the correct facts." |

5.Staying with the Feeling. If you have followed the first four steps carefully, you will likely feel some of the same emotions the other person is feeling. Experience that feeling. Determine what you can learn from truly feeling the experience of the other person. |

Second, it is important for managers to develop their ability to engage in empathic listening. Sparrow and Knight (2006) identify empathic listening as a type of listening that involves trying to understand the situation in the same way that the other person understands it and also trying to feel what she is really feeling. They indicate that there are five requirements for engaging in empathic listening: emptying oneself, paying attention, accepting the other person's reaction, avoiding judgment or comparison, and staying with the feeling. Table M1.2 summarizes these requirements for empathic listening.

Objective | The objective of this analysis is to give you an opportunity to analyze the behavior of others and discuss your observations in class. Because most people are not comfortable analyzing their friends and coworkers publicly, this exercise focuses on analyzing the behavior of fictional characters. |

Directions | Use the Johari window as a way to analyze the behavior of a character in a television program or movie as you watch it. You may want to watch with other classmates and compare your observations after you have developed your own ideas. |

1. Were there obvious instances of Hidden, Blind, and/or Unknown areas? If so, how would the course of events change if the character's Open area was larger? 2. Did any of the other characters attempt to make something in a person's Blind area known to them? If so, were they successful? Why or why not? | |

Reflection | Just as in real life, characters in popular television shows, movies, and books often behave in ways that either attempt to conceal their true feelings (Hidden areas) or reflect a lack of self-awareness (Blind and Unknown areas). Depending on the aims of the writers in fiction-based programs or the reactions of other cast members in reality shows, the results may be comic or tragic, and characters may end up enlightened or disbelieving. |

Objective | Increasing your self-awareness requires that you be open to receiving feedback. For many people, however, this is extremely difficult. Often, we tend to shut down and stop listening when someone is trying to give us constructive criticism. Defensiveness is natural, but can be costly— preventing us from learning more about ourselves and improving our personal effectiveness. The objective of this in-class role-play is to give you a chance to experience receiving negative feedback and to think about your responses to it. |

Directions | Your instructor will provide you with information for this role-play scenario. Working with a partner, one person should give feedback to the other person. After the first round of feedback, switch partners and have the people who previously gave the feedback receive feedback for the second round. |

Discussion Questions | 1. How did it feel to give negative feedback to another person? To receive negative feedback? |

2. Even though you knew that this was just a role-play, did you find yourself getting defensive orangry as you listened to the negative feedback? If so, why do you think that happened? | |

Reflection | Sometimes feedback is too vague to be helpful. Critical thinking skills can be used to develop feedback that is more effective. For example, rather than making a general claim such as "Tom has an attitude problem," describing specific examples of Tom's behaviors and demonstrating why those behaviors are causing problems in the workplace provides more clarity about what Tom needs to do to improve. |

Objective | Now that you have completed the first four steps of the learning process (assessment, learning, analysis, and practice), it is time to take what you have learned and apply it in the workplace and then reflect upon the results. |

Directions |

|

Reflection | Soliciting feedback is an important step in the process of understanding yourself, as well as improving yourself. As you continue to work through the competencies in this text, pay attention to your reaction to the different readings and exercises. If something strikes you as "trivial" or "a waste of time," ask yourself why you are reacting the way that you are. Sometimes we reject ideas because they conflict with our existing beliefs, and we don't take the time to think critically about whether our beliefs or the new ideas have stronger supporting evidence. |

Objective | The objective of this assessment is to provide you with insights into how you communicate differently with different individuals. Although every interpersonal relationship is unique, we can learn a great deal about our own communication patterns by observing how we communicate with different individuals and people in different positions. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Directions | Think about the communication patterns in two of your relationships—one that is very painful and one that is very pleasant—by assessing the degree to which each item listed creates a problem for you. Next, think about how your communication behavior varies in the two relationships and what areas of communication you might need to work on. Answer the questions by using the following scale. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Scale | Minimal Problem l 2 3 4 5 6 7 Great Problem

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Discussion Questions |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Reflection | Many people find it difficult to communicate with people with whom they have a negative relationship. Unfortunately, this can result in a downward spiral, as poor communication results in misunderstandings that may cause the relationship to deteriorate even further. In contrast, learning to communicate more effectively and practicing what you have learned may actually help improve negative relationships and strengthen positive ones. |

Interpersonal communication is perhaps one of the most important and least understood competencies that a manager can have. Arguably, it is at the heart of all the competencies you will encounter in this textbook. Studies consistently show that managers spend the majority of their time engaging in various types of communication—face-to-face, telephone, e-mail, teleconferences, memos, and presentations; organizational researchers see communication as central to the study of both managerial and organizational effectiveness (Tourish & Hargie, 2004). Knowing when and how to share information requires a very complex understanding of people and situations (Zey, 1991).

Communication is the exchange of information, facts, ideas, and meanings. The communication process can be used to inform, coordinate, and motivate people. Unfortunately, being a good communicator is not easy. Nor is it easy to recognize your own problems in communication. In the Assessment exercise you just completed, for example, you may well have downplayed your own weaknesses in communicating and rated yourself more favorably than you rated the other person in the painful relationship.

If, however, you practiced applying the critical thinking tactic described in the Introduction, identifying the grounds and warrants that support your claim, your assessment is likely to be more accurate than if you simply responded based on your initial impression of your behavior. Although most people in organizations tend to think of themselves as excellent communicators, they consider communication a major organizational problem and generally see the other people in the organization as the source of the problem. It is very difficult to see and admit the problems in our own communication behavior.

Despite this difficulty, analyzing communication behavior is vital. Poor communication skills result in both interpersonal and organizational problems. When interpersonal problems arise, people begin to experience conflict, resist change, and avoid contact with others. Organizationally, poor communication often results in low morale and low productivity. Given that organizing requires that people communicate—to develop goals, channel energy, and identify and solve problems—learning to communicate effectively is key to improving work unit and organizational effectiveness.

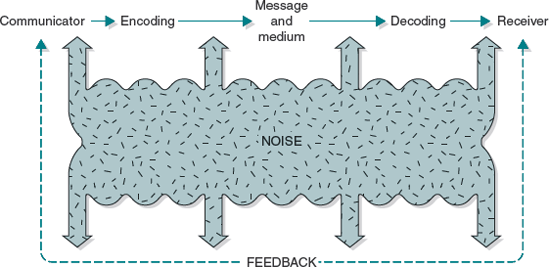

Whenever we attempt to communicate, the information exchanged may take a variety of forms, including ideas, facts, and feelings. Despite these many possible forms, the communication process may be seen in terms of a general model (Shannon & Weaver, 1948), which is shown in Figure M1.2. Although this model was developed over 60 years ago, it remains a useful tool for understanding how communication works and why it often fails.

The model begins with the communicator encoding a message. Here the person who is going to communicate encodes ideas into message, which is sent as a system of symbols, such as words or numbers. While you may not think of yourself as encoding your ideas when you plan to communicate, think about the differences between how you might convey an idea when speaking in class and how you might write that same idea in a paper, or the difference between a text message you might send to your friends to confirm when you are meeting and the e-mail you might send to your professor with the same message. The fact is, there are many things that influence how ideas are translated (encoded) into the message, including the urgency of the message, the experience and skills of the sender, the sender's perception of the receiver, and the sender's cultural expectations and experiences (Beamer & Varner, 2008). For example, in some cultures, a verbal agreement is enough to finalize a deal, while in other cultures a written contract is required. Moreover, each language has certain sayings and expressions that are unique to that language and sometimes difficult to convey to others from a different culture.

Figure M1.2. A basic model of communication. Source: Developed from C. Shannon and M. Weaver, The Mathematical Theory of Communication (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1948). Used with permission

Once the message is encoded, it must be transmitted through a medium (or channel) of some sort. A message, for example, might be written, oral, or even nonverbal. When choosing the appropriate medium, one consideration is the capacity of that medium to convey information, or what it often called the richness of that medium. Lengel and Daft (1988) developed a composite measure of richness based on how well the medium can deal with multiple pieces of information simultaneously, the degree to which the medium facilitates feedback, and the degree to which the medium allows for a personal focus. Based on this composite measure, face-to-face communication is considered the richest medium, whereas written communications, such as reports and general announcements, and formal numerical information, such as statistical reports and graphs, are considered the least rich. Lengel and Daft argue that one of the most important skills for a manager is to match the richness of the medium with the needs of the message, rather than merely using the richest medium available (see also Robert & Dennis, 2005). In recent years, newer technologies for mobile communications have been developed (e.g., Short Message Services for sending brief text messages and Multimedia Messaging Services for sending a variety of multimedia content such as photos and video) (Lee, Cheung, & Chen, 2007). As a result, managers have even more choices when selecting the most appropriate communication medium for their messages. For example, Paul F. Levy, the CEO of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, a major hospital in Boston, uses Facebook, Twitter, and a blog to communicate with his employees (Miller, 2009).

Once the message is sent and received, it must be decoded, which means that the person who receives it must interpret the message. Like the encoding process, the decoding process is subject to influence by a wide range of factors. Finally, there is a feedback loop between the receiver and the communicator. The feedback can take three forms: informational, corrective, or reinforcing. Informational feedback is a nonevaluative response that simply provides additional facts to the sender. Corrective feedback involves a challenge to, or correction of, the original message. Reinforcing feedback is a clear acknowledgment of the message that was sent. It may be positive or negative.

The model also includes the element of noise, which is anything that can distort the message in the communication process. As indicated in Figure M1.2, noise can occur at any point in the process. During encoding, a sender may be unable to clearly articulate the ideas to be sent. In the message, a document may leave out a key word. The medium used may have limitations, as when a voicemail system allows only a limited time for recording and cuts off the message before it is complete. Even if no problems occur earlier in the process, during decoding, the receiver may make wrong assumptions about the motive behind the message.

Effective interpersonal communication comprises two elements. First, individuals must be able to express themselves. They need to be able to convey to others what they are feeling, what they are thinking, what they need from others, and so on. Second, individuals must be good listeners. They must be open to truly hearing the thoughts and ideas that other people are expressing (Samovar & Mills, 1998).

Even if these two conditions are met, problems can occur because of characteristics of the situation. For example, the physical setting may be too hot, cold, noisy, or it may have other distracting features. In other cases, the situation might be inappropriate for the medium chosen. For example, in the movie, Up in the Air (Reitman, 2009), an organization discovered that firing people using a video meeting via computer was not as appropriate as meeting with people face-to-face. In contrast, some information should not be conveyed solely through face-to-face interactions. For example, most performance evaluations should be supplemented with a written document that includes an assessment of the prior period's performance, as well as expectations for the coming performance period. Also, oral presentations that include statistical analyses should be supplemented with charts and graphs. Similarly, formal messages may be inappropriate in settings that are highly informal, and informal messages may be inappropriate in a setting that is highly formal.

Here we list some barriers that reduce the effectiveness of interpersonal communication.

Inarticulateness. Communication problems may arise because the sender of the message has difficulty expressing the concept. If the receiver is not aware of the problem, completely inaccurate images may arise and result in subsequent misunderstandings.

Hidden agendas. Sometimes people have motives that they prefer not to reveal. Because the sender believes that the receiver would not react in the desired way, the sender becomes deceptive. The sender seeks to maintain a competitive advantage by keeping the true purpose hidden. Over time, such behavior results in low trust and cooperation.

Status. Communication is often distorted by perceptions of position. When communicating with a person in a position of authority, individuals often craft messages so as to impress and not offend. Conversely, when communicating with a person in a lower hierarchical position, individuals may be dismissive or insensitive to that person's needs. Similarly, a person may not be open to listening to the ideas and opinions of persons who are in a lower hierarchical position.

Hostility. When the receiver is already angry with the person sending the message, the communication will tend to be perceived in a negative way, whether or not it was intended that way. Hostility makes it very difficult to send and receive accurate information. When trust is low and people are angry, no matter what the sender actually expresses, it is likely to be distorted.

Distractions. If people believe that they can multitask while they are communicating, they may not be focused on the subject of the communication. For example, people may try to listen to a conversation while they are also listening to music or reading their e-mail. While this is especially true of the receiver, it can also be true of the sender. In addition, senders may create distractions by fidgeting while talking or looking away from their communication partner during a conversation.

Differences in communication styles. People communicate in different ways. For example, some people speak loudly; others speak softly. Some people provide a great deal of context; others get right to the point and are only interested in "the bottom line." Some of the many differences in communication style are attributable to personal characteristics, such as gender or cultural background. Misunderstandings can develop if people listen less carefully because they are distracted by or uncomfortable with another person's style of communication.

Organizational norms and patterns of communication. Communication barriers that stem from organizational norms and communication patterns may prevent individuals from asking questions or discussing difficult issues. For example, scheduling meetings with no time on the agenda for discussion is likely to stifle communication. Similarly, if every proposed change is routinely dismissed with "that's not the way we do things here," employees learn not to make suggestions.

When combined with the fact that individuals are often reluctant to engage in conflict, organizational norms that stifle communication can be extremely powerful barriers. As discussed in Competency 1 of this module, people have defenses that prevent them from receiving messages they fear. All people have some amount of insecurity, and there are certain things they simply do not want to know. Because people in organizations know this, they develop defensive routines (Argyris & Schön, 1996) in which they avoid saying things that might make the other person or themselves uncomfortable. Defensive routines are particularly likely to occur when discussing issues that relate to values, assumptions, and self-image.

Chris Argyris of the Harvard Business School refers to the thoughts and feelings that are relevant to a conversation but are not explicitly stated as "left-hand column issues" because of an exercise he uses to discover what they are (Senge, Roberts, Ross, Smith & Kleiner, 1994). Left-hand column issues include both the things people are thinking but not saying and the things they think the other person is thinking but not saying. You can think of left-hand column issues as things that are "left out" of the conversation. Argyris contends that organizations develop left-hand column issues that keep important issues from surfacing and being discussed. Instead of surfacing these issues, people work around them, avoid them, make things up, and say things they don't mean or believe. Often they go through these pretenses to avoid offending people or having to deal with a difficult situation. But when the list of "undiscussables" becomes larger than the list of "discussables," the organization begins to suffer. Trust erodes, and lots of covering up and avoidance make it difficult for people to improve their performance because they have no idea where they stand with one another. Important information is lost or kept concealed.

How does the left-hand-column exercise work? Imagine a conversation you have had or might have with a person at work. The person might be your boss, a coworker, or someone who reports to you. You could probably write down this conversation fairly easily, but before doing so, draw a vertical line down the middle of the paper. Now, in the right-hand column, write down the actual words spoken by you and the other person. In the left-hand column, write down the thoughts, feelings, questions, and concerns that you have but that you would not express out loud. Here's an example of such a conversation:

Left-Hand Column: What Is Thought (But Is Not Directly Communicated) | Right-Hand Column: What Is Said |

|---|---|

Terry: I don't want to wait any longer on getting this position filled. We've already waited too long as it is. | Terry: Have you had a chance to look at the memo with the list of candidates? If you have any questions or hesitations about who ought to be on the list, just let me know. I want you to be comfortable with the people we bring in to interview. |

Troy: I knew Terry wasn't going to add Michelle LaFleur to that list. We talked about it, and he knows I wanted her to be interviewed. | Troy: I think it looks pretty good. Have you gotten any feedback from the rest of the team? |

Terry: I know what he's thinking: "Does anyone else agree with me that LaFleur should be interviewed?" Why doesn't he just say it? That bugs me. | Terry: I haven't heard from anyone yet, but we've got three people out of town until Friday. They may get back to me before then on e-mail. I'd like to interview these people next week. Do you think that's possible? |

Troy: Right, another question from the guy who doesn't listen to my suggestions anyway. | Troy: I don't see why not. Let's move ahead with it. The last thing we want is to get stuck in a hiring freeze before we get someone in the door. |

Terry: I know Troy is miffed about this process. He gets frustrated because we don't follow his proposals, but he keeps putting unqualified people in front of us because he wants to work with them. He's always looking for friends instead of someone to get the work done. | Terry: I agree. Thanks, Troy. I think we're making progress. |

Clearly, these two people are not saying what they are thinking or feeling, but those feelings are influencing the "deep structure" of their behavior. The conversation on the surface is not as powerful as the silent conversation taking place beneath the surface, in the left-hand column. At the end of the right-hand column conversation that actually took place, both Terry and Troy feel somewhat dissatisfied, but neither one feels comfortable talking about the reason for their dissatisfaction.

People need to be trained to surface left-hand-column issues in ways that are positive and nonpunishing. They need to develop the skills to express their concerns in a way that helps the other person want to hear what they have to say. In the next competency, we will focus on mentoring and developing employees. In order to be able to perform this competency effectively, managers need to be open and honest with their employees. Effective managers also role-model these behaviors for their employees so that they can learn to be more effective at surfacing left-hand column issues.

Table M1.3. Rules for Effective Communication

1. Be clear on who the receiver is. What is the receiver's state of mind? What assumptions does thereceiver bring? What is she feeling in this situation? |

2. Know what your objective is. What do you want to accomplish by sending the message? |

3. Analyze the climate. What will be necessary to help the receiver relax and be open to the communication? |

4. Review the message in your head before you say it. Think about the message from the point ofview of the receiver. Do you need to clarify certain ideas? |

5. Communicate using words and terms that are familiar to the other person. Use examples andillustrations that come from the world of the receiver. |

6. If the receiver seems not to understand, clarify the message. Ask questions. If repetition is neces-sary, try different words and illustrations. |

7. If the response is seemingly critical, do not react defensively. Try to understand what the receiveris thinking. Why is he reacting negatively? The receiver may be misunderstanding your mes-sage. Ask clarifying questions. |

Of course, it is important to recognize that not all left-hand column issues should be communicated. In the conversation above, for example, it would most likely be helpful for Terry to explicitly state that he considered Michelle LaFleur but did not think that her qualifications fit the position. This might lead to a response from Troy that identified something that Troy had overlooked about Michelle. In contrast, it would not be helpful for Terry to say that he thought Michelle's only qualification was that she was a friend of Troy's, even if that was indeed how Terry felt.

Given the number and intensity of these barriers to effective communication, what should you know to help yourself to communicate effectively? First, you need to develop a few basic skills to express yourself more effectively. Table M1.3 gives seven basic rules for sharing your ideas with others. Most important, always keep in mind the old adage "Think before you speak." An effective speaker who communicates the wrong information can create far more problems than an ineffective speaker who struggles to convey the correct information.

Of all the skills associated with good communication, perhaps the most important is listening. The Stoic philosopher Epictetus, in The Golden Sayings, reportedly said, "Nature hath given men one tongue but two ears that we may hear from others twice as much as we speak." This is a good thought to keep in mind, but we should remember that listening is more than hearing what others have to say. Listening requires that we truly focus and try to understand what the other person is saying. Harris (2006) suggests that we should think of listening as having two dimensions: concentration and collaboration. Concentration involves focusing and attending to what the person is saying. Collaboration involves responding and providing feedback, letting the other person know that we are actively engaged in the conversation. When we define listening in terms of both of these dimensions, it becomes clearer that listening is a skill that we must develop, rather than one that we acquire as a by-product of how we hear.

Reflective listening is a tool that is based on empathy (recall Table M1.2), which helps us to experience the thoughts and feelings of the other person. In using empathy and reflective listening, instead of directing and controlling the thoughts of the other person, you become a helper who tries to facilitate her expression. Instead of assuming responsibility for another's problem, you help that person explore it on her own. Your job is not to talk but to keep the other person talking. You do not evaluate, judge, or advise; you simply reflect on what you hear. In fewer words, you descriptively, not eval-uatively, restate the essence of the person's last thought or feeling. If the person's statement is factually inaccurate, you do not immediately point out the inaccuracy. Instead of interrupting, you keep the person's flow of expression moving. You can go back later to correct factual errors.

The reflective listener uses open-ended questions, such as "Can you tell me more?" or "How did you feel when that happened?" Evaluative questions and factual, yes-or-no questions are avoided. Sometimes, it is simply helpful to mirror what the other person has said, but to turn it into a question that indicates that you want to hear more about that idea. The key is to keep the conceptual and emotional flow of expression. Instead of telling, the reflective listener helps the other person to discover. Here is an example of reflective listening to help illustrate how it works.

Kathie is the manager of the Training and Development Office in a large public agency. The office has 13 professional employees whose primary job is to conduct training for the agency and 2 secretaries. Allen is a relatively new employee who has been asked to develop new training on "Dealing with Crisis Situations." Kathie is having her first formal meeting with Allen since he was hired two months ago.

Kathie: Allen, I was wondering how you're doing on the new training program. I had originally hoped that during your first few months we would meet more often, but things have been very hectic. Are you moving along with the project?

Allen: Well, at first I felt like I was making good progress, but now I'm at an impasse. I'm just feeling frustrated.

Kathie: Can you tell me why you're feeling frustrated? Is there something about the project that isn't going right?

Allen: I guess I'm just frustrated with the assignment. I've gathered lots of information, but when I ask the others about what should be included, some say I'm putting in too much information, and others say there isn't enough time to practice the new skills.

Kathie: So are you feeling like you're getting different messages from different people?

Allen: Yes, and I'm not sure how long the training program is supposed to be. Is it a half-day program, a whole-day program, or a multiday program?

Kathie: Based on the information you have gathered, how long do you think it should be?

Allen: Well, I think it should be a two-day program, but I didn't think that I was responsible for making that decision. That's part of my frustration!

Kathie: I think I understand. Is part of your frustration that you're not sure which decisions you can make on your own and which you need to get approval from others?

Allen: Yes, that's exactly it. I'm not sure of what the rules are around here and how decisions are made.

To the first-time reader, reflective listening sounds very strange. Experience shows, however, that it can have major payoffs. Trust and concern grow with an ever-deepening understanding of interpersonal issues. More effective and lasting problem solving takes place, and people have a greater sense that their ideas are being listened to by others. In short, communication is greatly improved.

Reflective listening is not, however, a panacea. It is time-consuming to really listen. It requires confidence in one's interpersonal skills and the courage to possibly hear things about oneself that are less than complimentary. There is also a danger that the sender will get into personal areas of life with which the listener is not comfortable and for which a professional counselor would be more appropriate. It is, nevertheless, a vital tool that is seldom understood or employed.

Objective | This practice exercise is designed to help you enhance your ability to use reflective listening to surface left-hand column issues and clarify roles and expectations with another person—a boss, peer, or direct report. The two people in this case, Stacy Brock and Terry Lord, have gotten themselves into a box in their working relationship. They have already had one blowup, and they may have another if they cannot handle themselves effectively. Both need to listen to the other, both need some feedback, and both have things they need to say. |

Directions | Your instructor will provide you with a role description for either Stacy Brock or Terry Lord. Read the information carefully so that you are prepared to play your role from the perspective of your character. Your instructor may have some people role-play the situation in front of the class or may ask everyone to work together in dyads. After you have completed the role-play, respond to the following discussion questions. |

Discussion Questions |

|

Reflection | For many employees, performance evaluations are difficult conversations because they involve status differences. Both managers and employees may feel uncomfortable engaging in conflict with the other. If, however, the manager is able to use reflective listening effectively, a potentially explosive situation can turn into a very productive conversation where each can learn from the other. |

Objective | It is one thing to practice reflective listening in the classroom, but quite another to apply it in your daily life. The objective is this activity is to help you transfer what you have learned about reflective listening into a habit at work and at home. |

Directions |

|

Reflection | Techniques such as reflective listening are not difficult to understand, but mastering them requires repeated practice and reflection. The idea of keeping a journal about your experiences with reflective listening may seem time consuming at first, but it can provide specific ideas about where you need to increase your effort to develop your competence as an effective listener as well as more general feedback about how you are progressing in your development as a more effective communicator. The journal will also help remind you about the importance of practicing listening, in the same way you would practice any other skill you want to develop. |

Depending on your work setting, new employees may be expected to have a great deal of prior education or experience in the work performed in your organization, or they may be expected to learn much of their work on the job. Even within many work settings, some types of jobs may require individuals to have more knowledge and skills as they begin their work than others. For example, within a bank, most bank tellers do not know much about banking when they are hired, but are expected to have basic skills in communication and mathematics and to have a problem-solving orientation. On the other hand, when an individual is hired as a loan officer, he would likely be expected to be familiar with basic economic and accounting principles, understand marketing strategy and tactics, and also have good communication skills. Regardless of the knowledge and skills employees are expected to have when they are hired, your role as a managerial leader is to mentor and develop employees.

In a literal sense, mentor means a trusted counselor or guide—a coach. The term derives from a character in The Odyssey, the Greek epic poem written by Homer (Bell, 1996). In the poem, Odysseus asks a family friend, Mentor, to serve as a tutor and coach to his son, Telemachus, while he is off at war. In this section, we explore how managerial leaders can be more effective in mentoring and developing employees. We begin by examining formal organizational systems of performance evaluation and examine ways in which these can be structured to provide benefits to the employee, the manager, and the organization. We then look at mentoring and performance coaching as more informal processes that can be used to develop employees in an ongoing fashion. We conclude by looking at delegation as a means of developing employees' competencies and abilities by providing them with opportunities to take on more responsibility. While the primary focus here is on mentoring and developing employees, you should keep in mind that there are many other situations where you can apply the knowledge and skills presented here. For example, if you are a member of a club or community organization, you may have opportunities to mentor and develop others. Even outside of formal organizational settings, you may serve as a mentor to friends and family members.

In the Assessment exercise at the beginning of this competency, you chose between two options in eight pairs of assumptions about performance evaluation. In each pair of statements, answer a reflects traditional control values that provide the basis for most organizational performance evaluation processes. Evaluation processes that are based on these control values, however, are generally disliked by both managers and employees because they are generally associated with negative criticism (Jackman & Strober, 2003). Indeed, as you might expect based on your own experiences of being graded in school, performance evaluation is one of the most uniformly disliked processes in organizational America, as demonstrated by a survey of human resources professionals conducted in 1997 by Aon Consulting and the Society for Human Resources Management, which found that only 5 percent of the respondents were very satisfied with their organization's performance-management systems (Imperato, 1998). Since employees are not eager to hear criticism and managers fear negative reactions from employees, even to what managers see as constructive criticism, most individuals look on performance evaluation as a management process with little benefit to the organization, the manager, or the employee (Jacobs, 2009).

On the other hand, within the eight pairs, answer b reflects values rooted in involvement, communication, and trust. When performance evaluations are conducted within this perspective, they are not one-time, stand-alone meetings. Rather, from this perspective, performance evaluation is seen as part of an ongoing, multistage process that mixes the a and b views of the world by emphasizing both control and collaboration, and allows for regular feedback between the manager and employee.

Individual performance evaluations are a key component of an organization's comprehensive performance management system, a topic we return to in Module 3, where we will address how effective performance management systems translate the organizational vision into unit and individual goals. At the individual level, Grote (2002) presents a model of a strategy-based performance management system that includes four stages. The first stage, performance planning, begins a year before the actual performance review, and involves a meeting between the manager and the employee to discuss performance expectations for the next 12 months. Both the manager and the employee contribute actively to this discussion, which focuses on "the key responsibilities of the person's job and the goals and projects the person will work on" as well as "the behaviors and competencies the organization expects of its members" (p. 1). The discussion may also focus on specific development activities, such as attending a training workshop or webinar.

In the second stage, performance execution, the employee carries out his tasks and responsibilities, and the manager provides coaching and feedback on a regular basis. As you will see in the next section, coaching is generally seen as less formal than performance evaluation, but provides the foundation for that meeting. Grote suggests that the manager and employee should meet together midway through the year, and maybe more often, to discuss progress toward meeting goals developed at the performance planning meeting.

The third stage, performance assessment, involves gathering information on how well the employee has performed, and should begin a few weeks before the performance review meeting. The performance assessment should focus on how successful the employee was in reaching her goals, as well as how well the employee performed with respect to expected behaviors and competencies. Here, the manager may involve others in the organization who interact with the employee on a regular basis.

The final stage is the performance review meeting. At this meeting, the manager provides formal feedback on the employee's performance and suggests areas for development. During this session, you should be sure that your own objective is clear. Know what you want to accomplish. Get into an appropriate frame of mind (Krieff, 1996). Ask yourself how you really feel about the person and, most importantly, how you can really help the person. Few managers enter the process in such a frame of mind. Begin by making sure that the employee is also in an appropriate frame of mind. Remember that the performance evaluation will be most effective if the employee is ready to hear your feedback (Silberman, 2000).

Focus first on positive behaviors. If you have not already asked the employee to write a self-evaluation, ask him to list the things that he has done well; contribute to the list as much as possible. When you turn to areas that might need improvement, again ask the person to begin; in a supportive way, continue together until you agree on a list. At this point, you can use the skills discussed in the previous two competencies related to understanding self and others and communicating honestly and effectively and ask how you as a manager are contributing to this person's problems. For example, you might suggest going through the list and asking what you could do differently. As the person responds, use reflective listening to explore the person's claim in an honest way. Make commitments to change your behavior where possible. In doing so, you are modeling the behavior you would like the employee to practice and develop. After doing this, you might again go through the list and ask the employee what changes he might make.

Next, you should discuss the person's career development plan and what progress has been made with respect to the plan. If there is no such plan, one of the assignments should be to write a plan; you may need to help the person here. At the conclusion of the session, summarize what each of you might do differently during the next few months. After this, do an overall review, checking the employee's understanding of each action step. Do a final summary, and set a time for the next performance planning meeting.

While some organizations use the performance review meeting to begin the next cycle, Grote (2002) suggests that the next performance planning meeting should be held separately, but should build on the outcome of the performance review meeting. At that meeting, you should review the outcomes of the performance review meeting.

If your organization already has a system in place, you might consider its effectiveness from the perspective of employee growth and development. Does your current system consider employees' need for feedback? Does it encourage managers to engage in frequent conversations with employees during the time period from one performance evaluation to another? As noted above, managers should meet at regular intervals with each employee to provide specific feedback on employee performance and suggestions for improving performance. Table M1.4 provides some guidelines for giving feedback. While these guidelines are generally useful for both informal conversations and formal performance evaluation sessions, managers should recognize the differences between ongoing feedback and the performance review meeting. Bacal (2004) differentiates between the two by defining evaluation as focused on judging an individual's contributions, whereas feedback is more focused on "improving performance by making information available to the employee" (p. 146). To provide such information, managers need to make sure that they regularly observe the performance of employees and make notes of concrete incidents that can provide specific examples of both positive and negative behaviors.

Table M1.4. Guidelines for Giving Feedback

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In considering your organization's performance management system, you may also try to identify additional techniques for increasing employees' involvement, communication, and trust. For example, Jacobs (2009) argues that performance management systems should focus more on employees' perceptions of their work and suggestions for improvement than on the managers'. Of course, this would require that employees have access to other forms of feedback, either directly based on output or from others with whom they interact, such as colleagues or customers. Jacobs suggests that such a system helps develop employees to a greater extent because it gives them greater responsibility for their success. Even if the employee's perception does not drive the performance review meeting, you can ask the employee to prepare a written evaluation of her performance for you to read in advance of this meeting. By reading the employee's self-evaluation in advance, you can develop greater empathy and gain a better understanding of how this person sees her performance. In scheduling the session, be sure to set aside enough time to fully discuss the employee's self-evaluation and make sure that you have a private setting where you will not be interrupted. By allowing enough time and space to fully discuss the employee's self-evaluation, the session can become a learning opportunity for both yourself and the employee.

In the previous section, we examined the performance evaluation process and noted that it is generally disliked in organizations. One reason why performance evaluations are generally disliked is that managers and employees both tend to see the performance evaluation process as focused on control, providing managers with an opportunity to raise concerns about employees' poor performance. In contrast, the performance evaluation process also can be seen as focused on collaboration. From this perspective, the performance evaluation process provides an opportunity to celebrate an employee's successes and identify opportunities for new achievements in the future. In making suggestions about how to improve such systems, the focus was on finding ways to personalize the process and providing employees with more opportunities for input into the process. In recent years, there has been growing emphasis on two organizational processes that are designed to help employees grow and develop—coaching and mentoring. Both of these processes emphasize the one-on-one relationships between an employee and someone who is more experienced, either a coach or a mentor, and both emphasize the use of feedback as a tool for development.

Although the terms "coaching" and "mentoring" are often used interchangeably, many differentiate between the two, emphasizing that coaches tend to be the individual's direct supervisor, whereas mentors are often one or two levels higher in the organizational hierarchy and may even be in a different department or division. In addition, many organizations have formal mentoring systems, in which an individual is assigned a mentor, whereas coaching occurs when a trusting relationship develops between an employee and his supervisor so that the individual is able to grow and develop in his career and in the organization. In organizations that have formal mentoring systems, the focus of the mentoring relationship may be to help the protégé build his network within the organization, rather to provide feedback on specific work-related behaviors (Hughes, Ginnett & Curphy, 1999).

Gilley and Gilley (2007) identify a number of benefits of coaching to the individual, the manager, and the organization. Several of these benefits also occur when the relationship is with a mentor, rather than with a coach. For individuals, the greatest benefit is having the opportunity to develop to their fullest, which generally leads to greater job and career satisfaction. In addition, in coaching situations, individuals have the opportunity to work in a positive work environment. Managers also benefit from coaching; working with a more motivated and productive workforce energizes managers, which can result in further improvements to unit performance. In addition, Boy-atzis, Smith, and Blize (2006) argue that leaders who "coach with compassion" benefit because it reduces their personal level of stress. Finally, coaching benefits the organization, because there is better communication among managers and employees, as well as enhanced creativity in decision-making and problem solving, which ultimately leads to improved effectiveness and enhanced productivity.

The question then becomes: How do managers develop their skills and abilities as coaches? Gilley and Gilley (2007) identify four roles that coaches play: career advisor, trainer, performance appraiser, and strategist. Interestingly, these four roles bear some similarities to the quadrants of the competing values framework. Career advising has elements of the collaborate quadrant and focuses on being supportive and helping employees develop their self-awareness. As a trainer, the coach is more directive and takes on responsibilities associated with the control quadrant, focusing on specific information the employee needs to enhance her work performance. The performance appraiser is also directive, and takes on responsibilities associated with the compete quadrant, emphasizing goals and standards as a means to enhance performance results. Finally, the strategist focuses on developing employees using approaches associated with the create quadrant and is skilled at facilitating change. This suggests that to develop your capacity as a coach, you should develop your capacity to perform well in each of the quadrants and be flexible enough to switch between roles, depending on the needs of your employees. To better understand the needs of your employees, you especially need to build your capacity to empathize and understand your employees' perspectives. You also need to gain a strong understanding of their strengths and weaknesses so that you can encourage them to take on new tasks and responsibilities, as appropriate. In the next section, we focus on delegation as one approach to helping employees take on new tasks and responsibilities.

Most often, when organizational researchers examine delegation, they do so from the perspective of how it can help managers use their time more effectively. They note, for example, that managers who learn to delegate effectively provide themselves with additional time and thus are able to focus attention on more significant issues. By delegating tasks, managers can increase efficiency and productivity by ensuring that (1) the work is being done at the appropriate level and managerial time is saved for work that requires managerial attention and (2) employees are not waiting for managers to complete tasks that could be performed by others (Hughes, Ginnett & Curphy, 1999).