Organizing Information Flows

Working and Managing Across Functions

Planning and Coordinating Projects

Measuring and Monitoring Performance and Quality

Encouraging and Enabling Compliance

Joining an organization gives us an opportunity to work toward significant outcomes that we could not accomplish individually. To make that opportunity a reality, members must find ways to coordinate their activities. Complete flexibility without any control would result in chaos.

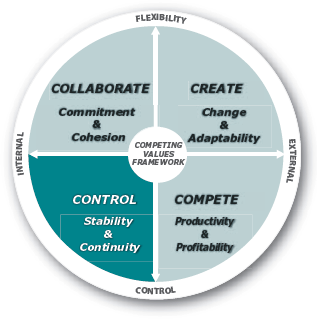

Organizational Goals. Just as commitment and cohesion are important for the success of organizations, so, too, are stability and continuity—the goals associated with the internal process model. Control is the action imperative of the internal process model based on the assumption that routinization will lead to stability and continuity. Key activities tend to be focused on internal issues and include defining responsibilities and measuring and documenting performance.

Paradoxes. While these activities are important, managers who create complex control systems often discover that excessive constraints on workers can paradoxically undermine the welfare of the organization. Similarly, an overemphasis on control also can result in getting the details right but failing to accomplish broader objectives. The paradoxical need to accomplish special projects while still completing day-to-day tasks is another challenge that managers focused on control must face. Perhaps the most common paradox associated with control, however, relates to the creation of bureaucratic red-tape. Over time, rules and procedures that initially increased organizational effectiveness later become impediments to performance.

Competencies. The five competencies included in this module are all valuable for contending with the paradoxes associated with control. They take into account the impact that people, as well as organizational processes, have on the stability and continuity of the organization. We begin with a discussion of organizing information flows. Information is the lifeblood of the organization, and managing information effectively is a critical aspect of a managerial leader's job. Next, we offer general guidelines for working and managing across functions and then go on to describe some specific tools that managers can use when planning and coordinating projects. Our fourth competency in this module, measuring and monitoring performance and quality, takes us beyond issues of process to consider the types of outcomes that organizations seek to achieve. Evaluating organizational outcomes has become even more complex in recent years, as social and political pressures have been applied to get businesses to think about more than just increasing the value of their stock. We conclude this module with the quintessential control question—how can managers encourage and enable compliance? We consider this question with respect to compliance with not only organizational rules and procedures, but also with legal and regulatory requirements for organizations.

New technologies have greatly increased the amount of information we receive and the speed at which requested information arrives. In the past we could write a letter, drop it in the mailbox, and then turn our attention to other things while we waited for a reply. Now, with fax machines, cell phones, laptops, and PDAs, responses can be immediate, pushing the work back onto our desks before we even have time to take a deep breath.

Back in 1997, David Shenk wrote, "Information overload has replaced information scarcity as an important new emotional, social, and political problem" (Shenk, 1997, p. 29). Since then, the problem has only gotten worse. In 2006 alone, the amount of digital data produced was equal to three million times the information contained in all the books ever written (Nordenson, 2008). It is no surprise then, that a recent survey of 650 professionals found that across 23 professions such as consulting, financial services, and education, 69.6 percent of respondents reported that they were overloaded by the amount of information they have to cope with related to their jobs (Davis, 2008).

Paradoxically however, even though managers have a smorgasbord of data at their fingertips, they also often claim to be starved for good information (Beard & Peterson, 2003). This apparent contradiction stems in part from our failure to distinguish between data and information. The term "data" refers to facts that have no particular context or organization and, as a result, data have no clear meaning. To make data meaningful, those facts must be organized and given context. It is in this way that data are translated into meaningful and, therefore useful, information (Beard & Peterson, 2003). To keep things simple in this text, we sometimes use the term "information" when it would be more accurate to say "data and/or information." Keep in mind, however, that if it isn't meaningful and useful, it really isn't information!

Russel Ackoff, an international consultant on managerial problem solving, says that a major problem confronting managers is too much irrelevant information. Managers are surrounded by data that do not tell them what they need to know but that demand attention anyway. Smart managers learn to watch the helpful data and ignore the irrelevant stuff. Less sophisticated managers drown in information anxiety. Richard Wurman, an expert on making information visually accessible, says, "Information anxiety is produced by the ever widening gap between what we understand and what we think we should understand. [It is] the black hole between data and knowledge. It happens when information doesn't tell us what we want or need to know" (Wurman, 2001, p. 14). See whether you identify with some of these symptoms of information overload as a student or employee:

Chronically talking about not keeping up with what's going on around you.

Nodding your head knowingly when someone mentions a book, an artist, or a news story that you have actually never heard of.

Assuming you must read every email you receive, regardless of who sent it.

Thinking that the person next to you understands everything and you don't.

Calling something that you don't understand "information." It isn't information if you don't understand it (Wurman, 1989, pp. 35–36).

The fashion of referring to virtually any kind of data as "information" emerged when we started using the word to describe anything that was transmitted over an electrical or mechanical channel (Campbell, 1982). The term "information" meant anything sent by any channel to any receiver, whether or not the receiver found it informative or interesting. "Information" has since become one of the most important terms in our society; however, much of the information we receive is really just unformed data.

We are inundated with bits and pieces of data, disconnected from any coherent picture, and yet we still feel guilty when we can't assimilate it. Information is probably best thought of as "that which reduces uncertainty." If the information we use is only adding to our uncertainty, it is probably data that have not yet been converted to information. Wurman (2002) suggests that most of us need to get beyond the anxiety of not knowing so we can begin to understand. He wants us to relax, feel less guilty about our ignorance, and begin to play with and exploit information instead of being controlled and intimidated by it. That is great advice, but how do we get to that point?

Today's managers are more harried than ever before, not only because of all the data coming at them from so many different sources, but also because many of them are now working without an assistant. Assistants have traditionally filtered a lot of information and transactions for managers, but many of these support positions have been eliminated from contemporary organizations. Thus, the individual manager has increasingly had to handle the channeling and managing of information. The bad news is that the problem of data overload is here to stay. The good news is that managers can become more efficient and effective if they learn and apply some tools and strategies for handling data inflows.

Good managers review all incoming data flows, but great managers are able to organize data efficiently, determine what information they need, and what information needs to be channeled to others. Great managers establish information management habits and systems that force them to do something quickly with every incoming piece of data, whether it is on paper, a digital recording, or an electronic message. Without a good system, you may not be able to wade through the insignificant stuff to find the information you need, when you need it. Managers need to set up and use a system that forces them to do something with every piece of paper that hits their desk and every email that appears in their inbox.

"Traffing," a method recommended by personal efficiency expert Stephanie Winston (Winston, 2004), is designed to end the inefficient practice of handling the same piece of paper many times. The same basic process can be applied to electronic messages, whether email or voice mail, which now make up the majority of most of the data inflows that inundate managers.

The metaphor of traffic control is wisely chosen because to control traffic, we have to give it places to go. Likewise, papers and emails have to be given a few basic routes or streams in which to flow. The list of items in front of you, all pleading for your attention, may be long; however, the number of choices you have for dealing with them is, fortunately, quite short. Winston's advice on Traffing gives you four options:

Toss papers into the wastebasket or recycling bin if they are not immediately valuable. Most of us are too conservative when deciding what to save. If you throw something out that you later discover you need, you can usually get another copy. For email, the electronic version of "tossing" is deleting.

Refer messages to other people (e.g., secretary, staff, colleagues). You should probably set up files for the people you most often refer things to. If you're not using routing slips, start immediately. You can usually save time by attaching a Post-it Note that briefly explains why you're referring the information. You can easily do the same for emailed messages and documents by forwarding them with an explanatory note.

Act by putting papers requiring your personal action (for example, writing a response letter or a brief report) in an action box or folder. These are the "hot" items you must act on before they get cold. In addition to placing documents in an "act" folder (physical or electronic). You should also record the action you need to take on your to-do list. The list is a very efficient reminder of things you need to act on. Plus, the act of putting them on the list will help you remember that you need to do them. Of course at some point, you will need to prioritize what is on your to-do list—we'll get to that topic soon.

File documents by indicating on the document itself the name of the file into which it should go. Put email that you need to save into folders. Put paper in a box or file labeled "to file." Even if you don't have an assistant who will file papers for you, it generally is more efficient to file papers on a periodic basis rather than getting up to file things while you are trying to clear your desk. Keep in mind that reading, in terms of this system, is a form of acting. If a document takes more than five minutes to read, put it in the "act" box. Don't let reading short-circuit your Traffing, or you'll never get the papers sorted. Make a clear distinction between Traffing and acting, and schedule time for doing both.

Traffing helps you wrap your mind around all the paper and messages you have to deal with and is an important step for dealing with data inflows. Even after tossing, referring, and filing, however, the number of items that end up in a manager's Action file is often overwhelming. Complicating matters further for managers is the fact that that they are frequently interrupted—the phone rings, a subordinate comes by to ask a question, a colleague stops off to see if you'd like to join him for lunch. Interruptions are difficult to avoid. The research firm Basex reported that "interruptions take up nearly 30 percent of a knowledge worker's day and end up costing American businesses $650 billion annually"(Nordenson, 2008).

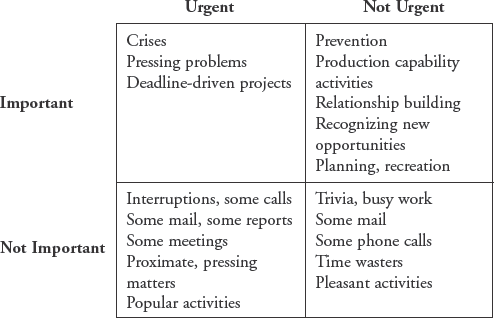

One approach to prioritizing suggested by Steven Covey in his book, The 7Habits of Highly Effective People is the Time Management Matrix (see Figure M2.1). Covey argues that we often fail to recognize the difference between Importance and Urgency and therefore allow ourselves to become bogged down in things that seem to be urgent, and we fail to devote time to what is important. Important action items are things that we need to act on related to our mission, values, and goals. Something is urgent when it requires immediate action. Because activities that are important have great significance or value, they often take a significant amount of time to complete.

Covey argues that in addition to avoiding spending time doing things that are not important, effective people also minimize the number of things that are important and urgent by spending more time doing things that are important but not urgent. As most of us have learned the hard way, tasks that are important but not urgent today, eventually become urgent as well as important if we do not attend to them.

Although people most often think about information flows in terms of the information that they receive, managers also have a responsibility to think carefully about the information that they pass on to others. Because we all suffer from information overload, effective managers must confront another paradox: employees don't want to be overwhelmed by unnecessary information, but they also typically do not want to be left out of the loop and be uninformed about what is happening in the organization. Deciding what information should be shared and what information need not be shared is not easy—but then, few things in management are!

One way to help you decide whether to forward an email or copy others on a message is to think about how a recipient using the Traffing method would be likely to respond to what you send. From a practical perspective, if it will just be Tossed, then you may want to leave their name off the list. Similarly, if you think a colleague will just Refer a request to someone else to do, you may be tempted to send it directly to the person who is likely to get the job. Politically, however, this could be a mistake—your colleague might think that you are trying to work around him, rather than realizing that you were just trying to save everyone some time.

Because email is such a common method for sharing important information, we offer a tool that can be used to compose your email messages. This tool can also be used for creating brief and concise voicemail messages for work and for personal use. By using this tool effectively, you can avoid confusing your customers, clients, and coworkers with unclear messages.

The OABC method was developed by William Baker, our colleague and a management communication professor at BYU's Marriott School of Management. Baker drills his MBA students on his OABC method for framing both email and voice-mail messages. This acronym stands for Opening, Agenda, Body, and Closing. The OABC method is a great antidote to the rambling and foggy messages that are sent out all over the world every day. This simple method requires you to make a very brief written or mental outline of the message. The outline of the message is usually best ordered in the following way:

Opening: A quick statement of greeting that sets a positive tone and also identifies you clearly, especially if you are a stranger to your audience. Even if you know the person well, it is often helpful to include your first and last name at the beginning of a voice mail to help the listener quickly put your message into context.

Example: "Hi, Chris, it's Karen Hooper. Great job on the presentation to the marketing group."

Agenda: An outline or map of what your message is about. Even brief messages usuallyneed a "frame" or border to go around them.

Example: "I have two things I wanted to share with you: The first is about the proposal to the Gartner Group, and the second is about a message I got from Kim Lee at the Ford Foundation."

Body: The "business" message itself, expressed in concrete and simple terms.

Example: "I think the proposal is solid, but it needs more work in the staffing section where we talk about our expertise in data warehousing. I'm attaching a document that gives you more specifics of what I think it should look like.

Second, Kim Lee at the foundation really needs us to have a representative at the awards luncheon. It's on July 17 at noon. Could you possibly attend in my place? I'll be in Toronto."

Closing: A concluding statement of what you want the person to do—who doeswhat by when?—and a cordial and efficient ending such as a simple thank-you.

Example: "Please look at the attachment and share it with the design team. I'll be back on Wednesday to discuss it with you. Also, please let me know by end of the day tomorrow if you can attend the luncheon, and I will call Kim myself from Toronto. Thanks. You've been a better teammate than I've been this week."

This message is more formal than one you might send to a coworker or friend whom you know very well. But notice that it's an easy message to "unpack." It has a pleasant tone, and it's coherent and complete. Chris knows exactly what Karen needs from him and when. Make a habit of using the OABC method in any message through any channel. We have used it with high-level managers and executives who have quickly added it to their toolkit. It can be applied to memos and business letters as well as to email and voice mail.

In addition to thinking about what information should be shared and with whom, it also is important to think about how best to share that information. Would a phone call be better than an email? Is this something that should be discussed face-to-face? Is a formal memo necessary? The answers to these questions depend not only on the content of the message but also on the characteristics of the intended recipient. Some people, for example, are much more responsive to voice-mail messages than to email messages. Some people avoid email and voice mail, preferring to stop people in the hallways when they see them to convey important information (not a method that we recommend!).

You also may discover that some people have trouble coping with emails that contain more than one topic. If Karen Hooper, in our example above, was sending an email to Chris and realized that he tended to focus only on the first topic in a message, she might want to send two separate messages, particularly because her first issue is something Chris is likely to take some time to get to, but he should be able to respond to the question about attending the luncheon immediately.

Messages can suffer from being too long and including too many issues, but they may even be more problematic when they are too short. The development of hand-held messaging technologies has resulted in the creation of a new "chat" language better suited to small screens. For example, in December 2008, Webopedia reported that there were over 1000 chat abbreviations. Unfortunately, often the same abbreviations are used to mean different things, depending on the online group that is using the abbreviation. O might mean Over, or Opponent to an online gamer, or "hugs" when used by friends (Text Messaging & Chat Abbreviations, 2010).

Unfortunately, as people become more and more accustomed to using these types of chat abbreviations, they have begun to filter into the workplace, where they can cause confusion. Therefore, although it may seem old-fashioned and cumbersome to those experienced in instant messaging, standard spellings are more appropriate for communicating in organizations.

Although changing technology has made it much easier to communicate across distances, there is no real substitute for face-to-face meetings, especially during the early stages of group formation. Box M2.1 talks about the importance of physical presence for building relationships.

Objective | This in-box exercise gives you a chance to analyze a typical pile of messages and documents that might appear on a manager's desk. | ||||||||||||

Directions | Imagine that, as the afternoon shift manager in a manufacturing plant, you have received the following documents during the previous few hours. Some are waiting for you in your email inbox. Others are physical documents resting in the in-basket on the corner of your desk. Using the Traffing method, first decide whether you would Toss, Refer, Act, or File these documents. For the items that you marked as Act, note whether they are Important and Urgent (I/U), Important but Not Urgent (I/NU), Not Important but Urgent (NI/U), or Not Important and Not Urgent (NI/NU). Then, rank the Act items in the order that you plan to do them. Don't worry, for the moment, that you lack contextual details on each of these items. Just do your best to think through how and why you would respond to each item. You may find it helpful to put your responses in a table like the one below:

After you have done this task on your own, your instructor may ask you to discuss and defend your choices in a small group. See how much agreement your group has in "Traffing." Disagreement is not uncommon in this exercise. People's choices are based on their assumptions about the situation, as well as their attitudes toward delegating responsibility and their own priorities, which reflect their personal values.

| ||||||||||||

Reflection | In the directions for this exercise, we told you not to worry about the contextual details. In reality, of course, context is very important for deciding the relative priorities of tasks. Taken out of context, a sign-up sheet for a blood drive might seem unimportant, but within the culture of a health organization or the Red Cross, that activity might take on much more importance as a symbolic act in support of the values of the organization. Similarly, although the shift manager may not need to do anything with the accident report, she may decide to file it rather than toss it. Why? Because symbolically, tossing the report might suggest a lack of concern for employee safety. |

Objective | The purpose of this exercise is to help you identify where you fit within your organization and how you are connected to other areas. Understanding how the different parts of your organization fit together can help you more effectively apply some of the other competencies that you are studying. For example, with regard to organizing information flows, understanding the overall organization structure will help you identify where you should seek information as well as where you should send information. |

Directions |

|

The formal structure found in most organization charts is often only a modestly accurate representation of how things actually work. Effective managers need to understand not only the official roles and responsibilities in the organization, but also need to recognize the informal networks that can help (or hinder) task accomplishment. |

More than 20 years ago, the authors of Made in America: Regaining the Productive Edge argued that to be successful in the global economy, U.S. companies needed to have greater functional integration and less organizational stratification because functional silos often result in inefficiencies in communication and coordination, the very functions that hierarchical structures were intended to support (Dertouzes, Lester, Solow & the MIT Commission on Industrial Productivity, 1989). Over the next 10 years, many companies attempted to heed that advice. Reengineering the Corporation by Michael Hammer and James Champy (1993) became a best-seller. Companies began to establish teams made up of specialists from different functional areas. These cross-functional teams became especially popular, in part because they did not require excessive disruptions to the existing organizational structure. The results of cross-functional teams, however, did not always live up to their promise. For example, a study looking at 93 research and new product development teams found that functional diversity, per se, did not improve team outcomes. It was only when external communication increased due to "having members with diverse backgrounds and areas of expertise and diverse contacts with important external networks of information" that benefits were realized (Keller, 2001).

Despite growing evidence that cross-functional teams are not a panacea, their use continues to grow, driven in part by the changing nature of work (Cross, Ehrlich, et al., 2008) New technologies that allow work to be done around the globe have become increasingly affordable. Companies have outsourced activities and depend on other organizations to do tasks that were formerly handed internally. These changes have resulted in additional flexibility and also resulted in additional costs that need to be accounted for and controlled. "Teams today are frequently formed and disbanded rapidly, distributed across multiple sites, and composed of members simultaneously working on myriad projects, with different bosses, competing for their attention. Further these teams' work increasingly demands substantial coordination and integration of specialized expertise within and outside of the team" (Cross, Ehrlich, et al., 2008).

As described in the next section, working in and managing these types of cross-functional teams poses new challenges compared to working in a traditional functional organization. An additional set of challenges is faced when working in organizations with potentially competing divisions, a topic we address in the subsequent section.

Following the principles of Adam Smith and Henri Fayol, organizations have traditionally organized work by creating departments that handle the different functions of the organization. When departments within a single organization are structured differently so that they can each approach their own task in a way that is most efficient for that particular department, we refer to this as differentiation. In traditionally designed organizations, differentiation is accomplished through the creation of specialized jobs and work units that are then organized hierarchically. Within this hierarchical system, labor is divided up so that individual contributors perform the organization's work. Consistent with this approach, performance-management and reward systems focus on the individual performer. Job evaluations and job descriptions clearly specify who does what and who reports to whom. Status differentiations are made clear by labels such as "labor" and "management," "bonus eligible" and "bonus ineligible," and so on. Organizational subunits typically consist of individuals with similar expertise performing similar tasks—engineers engineering, marketers marketing, and manufacturing experts manufacturing.

Although there is no question that differentiation can result in improved efficiency in many situations, it does have some negative consequences that result from employee self-interest. For example, employees concerned about their careers often become focused on moving up the hierarchy, rather than on adding value to the output of the organization. Because budget size and the number of people one manages are symbols of position and power, managers may make decisions that are more consistent with increasing their hierarchical control than in delivering products or services to a customer (Mohrman, 1993).

Even if all employees were willing and able to subordinate their own individual interests to the general interests of the organization (as Fayol's principles of management required), there would still be costs associated with differentiation. An organization that is differentiated as a consequence of its traditional structure will eventually need to coordinate or integrate the work that is being done across units. Differentiation and integration can be likened to the flexibility and control dimension in the Competing Values Framework—both are needed even though they may appear to be diametrically opposed.

Integration is primarily accomplished by processes inherent in the organizational hierarchy. Processes and procedures are standardized and formalized, specifying how the work is to be done and the sequence by which it is to proceed through the organization. Individual contributors are managed, directed, controlled, and coordinated by middle-level managers who receive strategic guidance from senior-level executives. These types of integrative processes work fairly well for relatively simple and static situations, but it has long been known that their effectiveness is limited in complex, dynamic, and turbulent environments (Galbraith, 1973). For example, in 1993 Mohrman argued that organizations had to simultaneously:

Achieve multiple focuses (on product, market, customer, and geography) without segmenting the organization in a dysfunctional way.

Align individuals and groups that are task-interdependent in a manner that fosters teamwork in pursuit of shared overall objectives.

Enable quick, low-cost, high-quality performance while responding to a highly dynamic environment that calls for ongoing change.

Respond to ongoing increases in competitive performance standards by learning how to be more effective.

Attract, motivate, develop, and retain employees who are able to operate effectively in such a demanding organizational environment.

Taken together, these goals pose several paradoxes for managers. How can we be focused if we are trying to address multiple sets of needs? How can we evaluate individuals when they are working in teams? How can we keep quality high while we are working faster and cheaper? How can we keep costs down if we are constantly changing standards? How can we find employees who will stay committed when the organization is constantly changing?

Because most people see paradoxes in terms of either/or decisions, it is not surprising that some organizations attempted to respond to these challenges by "throwing away their organizational charts in favor of ever-changing constellations of teams, projects, and alliances" (Dumaine, 1991, p. 36). Other organizations have attempted to manage these challenges within more traditional structures; some have gone back and forth, at times favoring cross-functional diversity and at times retreating to more specialization (Sapsed, 2005). Theoretically, incorporating cross-functional teams into a traditional structure can provide the integration solution to the need for integration in differentiated organizations, but like so many good ideas, this solution comes with its own set of challenges.

Parker (1994) identified a number of challenges for cross-functional teams, particularly those that are formed as a result of a need to respond quickly to competitive pressures. Lack of clear and consistent support from senior management can undermine the best efforts of any cross-functional team. One type of support that can be valuable is having a physical space for the team. Co-locating team members has symbolic, as well as substantive benefits. Cross-functional teams also suffer when all of the relevant functional areas do not become involved early in the process. Projects that start out in one functional silo and then try to add team members from other functional areas may end up with teams where there is a lack of trust. Cross-functional teams can also be hindered if the allocation of work across functions seems inequitable or is inefficient, or if decisionmaking processes are not clearly defined. With respect to product development teams, making sure that the team moves quickly based on customer input is often a challenge because team members are typically still engaged in working on tasks associated with their functional area. Despite all these challenges, cross-functional teams can be a valuable tool in organizations, if they are effectively managed.

What is needed is a set of processes and devices that are consistent with the complex and dynamic environment that the organization faces and that allow organizations to integrate and coordinate their efforts, regardless of the formal structure of the organization. In essence, managers today need to be able to create ad hoc structures that can both transcend and operate within a traditional organizational design. The guidelines below can be helpful in accomplishing that objective.

The guidelines below are derived from Dumaine (1991), Meyer (1993), and Parker (1994).

Clarify goals and charter and get team buy-in. The cross-functional team will generally take the formal charge from senior management, but the team must also feel ownership over the goals. In the Managing Groups and Leading Teams competency in Module 1, we discussed the importance of being committed to a common goal or purpose and indicated that this is the glue that holds the team together. Sometimes the cross-functional team will need to meet with senior management to negotiate the goal or to make sure that there is a shared understanding.

Seek to create a critical mass of leadership. While a single functional unit can generally get by with a single leader, most cross-functional teams cannot. If the ultimate purpose of cross-functional teams is to make optimal use of people from different functions, each of these functions must have a strong leadership voice. In addition, this is a good time to take advantage of team members' unique talents (Buckingham, 2005).

Hold the team and its members accountable for its performance. Once team members have bought into the goals, they must also buy into the process. Everyone must feel responsible for the team's performance. Team goals should be translated into clear short-term objectives and milestones that are constantly visible and in the forefront of everyone's thinking. While senior management should avoid micro-managing, they should hold the team to standards. When standards are not met, questions should be raised in such a way that team members feel supported rather than attacked.

Keep cross-functional teams as small as possible with critical functional representation. While the purpose of creating a team is to bring together a diverse set of perspectives, years of research on group processes shows that as group size increases, there is a loss of productivity that results from increased time devoted to coordination and communication. One estimate of productivity loss indicates that in groups with as few as five people, between 10 and 30 percent of team members' time is spent communicating with other team members about the task (Parker, 1994). Alternatively, if there is not sufficient representation of all functional areas from the very beginning, the team will not be able to perform effectively. One solution is to break up the large group into smaller groups, with each small group having representation in a central decision-making group. In addition to determining the optimal team size, finding the right mix of people is critical. If all functional areas are represented, but one team member cannot see the value of working on a cross-functional team, size will quickly become a secondary issue.

Provide the cross-functional team with constantly updated and relevant information and the authority to make decisions. If an organization is to make heavy use of cross-functional teams, it must essentially rewire the information system so that cross-functional teams have ready access to the information they need to do their jobs. Teams also need what was formerly assumed to be the prerogative of management: the authority to make decisions.

Train members in teamwork and process management. Operating in cross-functional teams with complex and fuzzy authority and reporting relationships necessitates that members know the core skills of teamwork. In Module 1, Competency 4, "Managing Groups and Leading Teams," we presented some of these core skills, including defining roles and responsibilities, using participative decision-making, and managing meetings. As was noted in that competency, teamwork does not develop naturally. There needs to be a conscious effort to develop as a team, and organizations must often be willing to make the investment to give people training in interpersonal skills.

Clarify expectations within and between teams. Each individual who is part of a cross-functional team has three responsibility perspectives: the team, the function, and the larger organization. Each of these should be clearly articulated before the start of the project. Moreover, leaders of cross-functional teams must have the ability to develop effective relationships with key stakeholders, including leaders of functional departments, senior management sponsors, and other resource people in the organization. The next competency in this module, Planning and Coordinating Projects, presents the notion of internal and external integration and suggests that regular communication with key project stakeholders is an important element of managing projects. This is even more true if the project is being carried out by a cross-functional team, where the definition of who is internal and who is external can become somewhat blurred. While it is clear that all organizations have multiple and often competing goals, these competing goals must not become a barrier to effective cross-functional team management. An organization will be able to use cross-functional teams effectively only if team members and others in the organization identify primarily with the larger organization and only secondarily with their functional units.

One step that is often useful here is the co-location of team members. That is, whenever possible, cross-functional team members should be located as close as possible, "in the same building, on the same floor, and in the same area" (Parker, 1994, p. 78). Physical proximity allows for more regular and more informal interactions. Co-locating team project members also sends a very clear message regarding the importance of the project.

Encourage team members to step out of their roles. As a corollary to the previous guide-line, we suggest that people must not only be willing to step out of their functional identity to "put on an organizational hat," they must also be willing to step out oftheir status or rank identity to allow for more optimal use of everyone's unique skillsand abilities. As noted in the second guideline, the increasing use of cross-functionalteams suggests that more and more, "leaders" on one project will be "followers" on the next. In sum, the most successful teams are ones that are able to manage the paradoxes that are associated with having clearly defined roles and responsibilities, while simultaneously expecting that everyone will step up when necessary to ensure that everything that needs to be done, is done.

Identifying the right members for a cross-functional team depends on a number of variables, as noted in the guidelines above. In addition to considering the technical skills of team members, however, it is also wise to consider their interpersonal skills. As we have seen, working effectively on a cross-functional team can be very challenging. The complexity of the task itself often pales in comparison to the political issues that tend to emerge when managing across functions. In these types of situations, it is helpful to have individuals on the team who are not only energetic themselves, but who tend to energize the people around them. Empirical research from the field of network analysis has identified a key variable "energizing relationships" (Baker, Cross & Wooten, 2003) that is worth considering when creating cross functional teams.

Most people have had the experience with working with someone whose enthusiasm, optimism, and vitality seem to charge up everyone around them. Intuitively, we know that these are the kinds of people whom we want working on important projects. Network analysis research confirms that intuition and goes further to suggest that the ability to develop energizing relationships "may be more important than occupying certain positions in an information or communication network" (Baker et al., 2003, p. 339).

Recent work on the concept of "lift" provides additional insights into the characteristics of individuals who may be likely to create energizing relationship. In their book Lift: Becoming a Positive Force in Any Situation, R. W. Quinn and R. E. Quinn define "lift" as "influence, an uplifting effect we have on others." This definition is consistent with Baker et al.'s concept of energizing relationships. The authors go on to identify four key thoughts and feelings that, when present, cause individuals to feel uplifted and to lift the people around them. Specifically, individuals feel uplifted and lift the people around them when they are:

purpose-centered — they have a purpose that is not weighted down by needless expectations [Compete];

internally-directed — they have a story of how their personal values will guide their actions [Control];

other-focused — they feel empathy for the feelings and needs of others [Collaborate]; and

externally-open — they believe that they can improve at whatever it is they are trying to do [Create] (Quinn & Quinn, 2009, p. 3).

As noted in the brackets after each factor above, these four key thoughts and feelings map directly onto the action imperatives in the competing values framework, a point we address in more detail in the concluding chapter of this text. Further information on the concept of "lift" also can be found at http://www.leadingwithlift.com.

Unfortunately, like the manager in the Analysis that follows, you will not always be able to choose the members of the teams with which you work. Fortunately, you can have much more control over your own thoughts and feelings.

ANALYSIS Errors in the Design?[5]

Directions | Read the paragraph below. It comes from a real situation encountered in one of the Big Three U.S. automobile manufacturers. Diagnose the errors that might have been made in managing across the various functional areas that were involved in designing the automobile. The total amount of electrical power in a vehicle is determined by the capacity of the alternator. The power must serve over twenty subsystems, such as the stereo, the engine, the instrument panel, and so on. These subsystems are developed and controlled by separate "chimney" organizations, and power allocations must be made for each subsystem. The problem was, in this vehicle program, when the requirements of all the chimneys and teams were added up, they equaled 125 percent of the capacity of the alternator. Keith, who had recently taken over as head of this vehicle program (which had made changes in direction and was behind schedule to begin with), called a meeting of the Program Steering Committee designed to resolve this conflict and reach a compromise. However, many of the chimney representatives who were members of the team came to this meeting with instructions from their bosses [who, incidentally, did their performance appraisals] not to make any compromises, but to make certain that their chimney "got what it needed" and "didn't lose out." After Keith presented the group with the problem and the need to reach a compromise solution, their response surprised him: "It's not our problem," they replied, "it's your problem." |

Questions |

|

Reflection | For people who have not experienced the type of situation described above, the story seems almost unbelievable—How could members of the same organization not recognize the importance of coming up with a vehicle design that would actually work? For far too many employees, however, this type of situation rings all too true. Consistent with a sociotechnical systems perspective, organizational structures and processes can result in inefficiency and even divisiveness if people do not understand and respect the interconnections among all functions in the organization. |

Objective | Many events require cooperation across different groups, but special issues often come into play when the groups involved are made up of volunteers. In this exercise you need to think not only about the task issues, but also the people issues given the volunteer nature of the groups who will be participating in the event. |

Directions | You are president of the University Students Services Association (USSA). USSA is a student-run organization that coordinates the activities of all other student-run organizations on campus. USSA monitors scheduling of all extracurricular activities, tracks consistency of student organization activities with university policy, and attempts to provide resource support whenever possible. In the past, each major university organization—such as Academic Support Services, the USSA, the Student Health Services, the Honor Society, and so on—conducted its own new-student orientation during the general orientation prior to the beginning of the fall semester. These orientations typically lasted anywhere from one to three hours and included speeches, presentations, videotapes, and workshop-type activities. For most organizational units, these orientations were seen as an opportunity to publicize the way in which they contributed to students' experience of university life. Organizational units spent a great deal of time, effort, and attention in preparing their individual orientations, because they felt it was important for students to learn about how they might take advantage of the services provided. Organizational units took great pride in conducting a professional presentation and paid close attention to the evaluations that students completed. In fact, there was something of an informal competition among the units, with each trying to be the most innovative in its presentation. This year the provost has decided to try a new approach, declaring that all student orientation sessions will be centrally coordinated and run over a three-day period during the first week of classes. You have been asked to head the team that coordinates this orientation. Your first task is to prepare a one-page outline of how you will approach this new responsibility. After you have completed the outline, respond to the process questions below. |

Process Questions |

|

Reflection | Planning, of course, is only the beginning. Before any plan can be implemented, people will need to be convinced to go along with the plan. This is where the competencies such as Championing and Selling New Ideas and Negotiating Agreement and Commitment (see Module 4) come into play. |

Objective | This exercise is intended to prime your thinking about effective project management by encouraging you to reflect on your past project experiences. |

Directions | Think about a project or event you have worked on, preferably one in which you had some leadership responsibility. (Note that having leadership responsibility does not necessarily mean that you were the sole project leader.) Think about the planning and coordination, and respond to the questions below.

|

Reflection | As we noted in Module 1 in the Managing Groups and Leading Teams competency, when a project is assigned there is often a tendency to try to skip over the planning and coordination tasks, and to dive directly into working on the project. Effective managers recognize that this is a mistake. Looking back at your prior experiences with project work gives you an opportunity to identify any points where planning and coordination broke down. As you read the Learning material for this competency, think about whether the tools and techniques described would have helped you to avoid those problems. |

World-class organizations must be adaptable and flexible to succeed. What worked yesterday may not work today. As we have seen in the competing values framework, flexibility needs to be balanced with stability. To be more flexible, improve performance, and prepare for the future, many organizations are coming to rely on nonroutine projects (Anatatmula, 2008). To balance that flexibility, projects are assigned specific objectives, starting and ending times, and a predetermined budget. In the end, financial stability depends both on identifying the correct projects from a strategic perspective (a topic we take up in Module 3) as well as on effective and efficient project management (Schmid & Adams, 2008). In this competency we discuss some tools that can be used when planning, directing, and controlling resources to meet the technical requirements, cost targets, and time constraints of a project.

Although projects were originally used primarily in the military and construction industries (Baltzan & Phillips, 2008), changes in the economy, heightened competition, increased complexity in organizational environments, and rapid technological changes have created ideal conditions for project teams to spread to other organizational areas. For example, human resource managers benefitted from using project management tools when Life Technologies Corp, a biotechnology tools company, was created as the result of a merger of two smaller organizations (Robb, 2009). Today, project management concepts are being applied in a diverse array of industries, including pharmaceuticals, banking, hospitals, law, state and local governments, and the United Nations (Kerzner, 2009).

Project teams are seen as an ideal approach to deal with the need to respond more quickly to changes in the turbulent business environment for several reasons. First, project teams are task focused, thus complementing the way many organizations allocate work—through tasks. Project teams also enable companies to engage the work through the use of cross-functional teams, as discussed in the previous competency in this module. Lastly, because project teams make use of resources borrowed from within the firm, and perhaps also from outside the firm, they are flexible and able to act and react quickly to change (Frame, 1999).

Harold Kerzner, one of the leading authorities on project management, summarizes the five different process groups included in the PMBOK® Guide from the Project Management Institutes as follows:

Project initiation

Selection of the best project given resource limits

Recognizing the benefits of the project

Preparation of the documents to sanction the project

Assigning of the project manager

Project planning

Definition of work requirements

Definition of the quality and quantity of work

Definition of resources needed

Scheduling the activities

Evaluation of the various risks

Project execution

Negotiating for the project team members

Directing and managing the work

Working with the team members to help them improve

Making adjustments

Project monitoring and control

Tracking progress

Comparing actual outcome to predicted outcome

Analyzing variance and impacts

Making adjustments

Project closure

Verifying that all of the work has been accomplished

Contractual closure of the contract

Financial closure of the charge numbers

Administrative closure of the paperwork

(Kerzner, 2009, p. 3)

In this competency, we focus on planning and monitoring; activities associated with the other three categories (initiation, execution, and closure) are addressed in other competencies in this text. For example, communication skills are considered one of the most critical skills for project managers (Henderson, 2008).

The various tools of project planning and project monitoring that we focus on for this competency are closely tied. Planning clarifies the work to be accomplished and sets priorities for task completion. Planning involves scheduling—establishing timetables and milestones for completion—and resource allocation—developing a budget that forecasts the amount of labor and equipment that will be needed. Alternatively, monitoring tracks progress to see whether the project is proceeding as planned. Is the schedule being adhered to? Are milestones being met? How likely is the project to be completed within, or even under, the projected budget? In the next two sections, we will present several key planning and monitoring tools. It should, however, be noted that the monitoring tools will be useful only if the planning has been conducted carefully, with sufficient attention to detail.

Project planning is not simply deciding on an outcome to be achieved. Project planning should make clear the path the project is expected to take as well as the destination. Consequently, the planning process should focus attention not only on the goals and objectives of the project but also on such issues as the technical and managerial approach, resource availability, the project schedule, contingency planning and re-planning assumptions, project policies and procedures, performance standards, and methods of tracking, reporting, and auditing (Badiru, 1993). It is thus evident that planning is far more complex than scheduling. Indeed, while scheduling is considered a key element of coordination, it is actually the last step of the planning process and depends on the existence of a precise statement of goals and objectives, accompanied by a detailed description of the scope of work. Below we present some of the key planning tools available to the project manager, with the order of presentation based on the order in which they are likely to be used.

Today, many of these tools can be found in project management software programs such as Microsoft Office's Standard Project 2007 and Enterprise Project Management (EPM) Solution. These types of products incorporate the basic planning tools discussed below and simplify planning, monitoring, and coordinating processes by integrating all data relevant to the project. For example, data associated with the Statement of Work and Work Breakdown Structure (discussed below) related to specific tasks, working times, schedules, deadlines, people, materials, machines, and so on can be entered into computerized templates. During the data entry process, the software can also provide prompts to help establish the order in which work needs to be completed if two tasks are dependent. As data on tasks, times, and schedule are entered, the computer can generate PERT and Gantt charts, as well as other types of reports. Because not every organization requires a full-blown project management software system, a variety of other programs have been developed to address users with different needs. One example is Basecamp, a web-based program available by subscription from 37signals. The program's "to-do list" feature is used to enter information traditionally found in the Statement of Work. Milestones and a time tracking feature are available to help monitor progress. Although Basecamp lacks the capacity to produce PERT and Gantt charts, its ease of use appeals to its clients. Because new project management software and features are constantly being developed, we do not attempt to provide instruction on how any particular program works. Rather, we focus on explaining the fundamental concepts upon which those programs are based.

The statement of work (SOW) is a written description of the scope of work required to complete the project. It should include a statement regarding the objectives of the project, brief descriptions of the services to be performed and the products and documents to be delivered, an explanation of funding constraints, specifications, and an overall schedule. Specifications should be included for all aspects of the project. They will be used to provide standards for determining the cost of the project. The overall schedule should be more general, including only start and end dates and key milestones.

The statement of work may also include brief descriptions of the tasks necessary for project completion as well as a description, where appropriate, of how individual tasks will be integrated into the whole. Alternatively, this information may be included in the work breakdown structure.

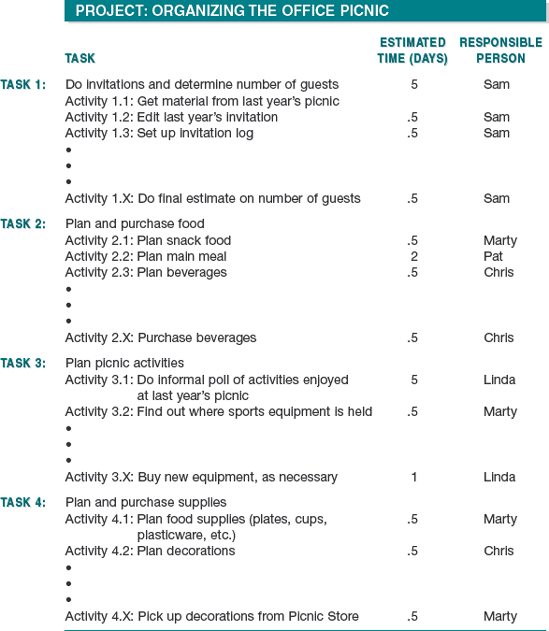

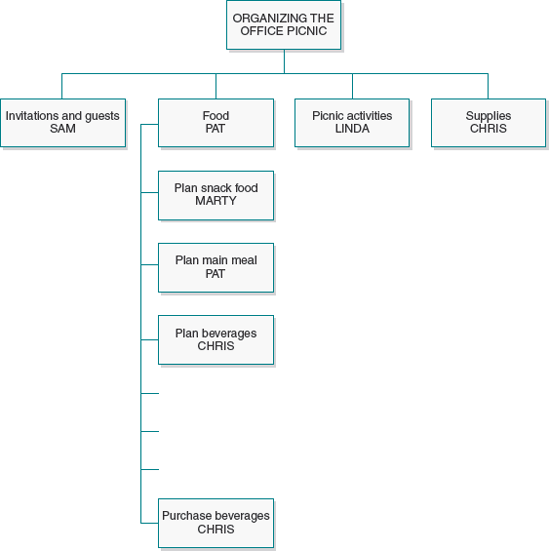

The work breakdown structure (WBS) shows the total project divided into components that can be measured in terms of time and cost. It may be presented in tabular or graphical form, or both (see Figures M2.2A and M2.2B). Whether in tabular or graphical form, the WBS divides the project into a series of hierarchical levels; in graphical form it resembles an organizational chart of tasks (rather than positions). The complexity of the project and the degree of control desired during project monitoring will determine the number of levels. Badiru (1993) suggests starting with three levels, with level 1 being the final or total project, level 2 being the major tasks or subsections of the project, and level 3 containing definable tasks or subcomponents of level 2. Again, if the project is very complex, the WBS should include additional levels, until the final level specifies discrete activities that can be examined in terms of the time and cost required to complete the activity.

At the final level, the work breakdown structure should include at least two pieces of information that are needed for coordination of effort: the estimated time to complete the activity and the name of an individual who is responsible for seeing that the activity is completed. Often a third piece of information, the estimated cost of completing the activity, is also included. This allows for better integration of cost and schedule information needed to monitor the project. When cost information is included, people refer to the work breakdown structure as a costed WBS. Time and cost estimates should be developed by the persons most knowledgeable about those specific activities. Thus, if project team members come from different functional areas, the project manager should likely consult with managers from those different functional areas before making time and cost estimates.

The WBS provides information on the estimated time of completion for each individual activity, but it does not indicate the order in which the activities can or will take place. It does not indicate whether Activity A must be completed before Activity B can proceed, or whether the two can proceed concurrently. When a project is fairly simple, these interrelationships are not difficult to discern, and a schedule can be constructed directly from the WBS by laying out the activities in the order in which they are to be carried out (see the section on Gantt charts, later in this competency). Alternatively, when a project is complex, it is almost impossible to construct a schedule before the interrelationships among the various activities are made explicit. Network diagrams are graphical tools for making these interrelationships explicit.

In the late 1950s, Program Evaluation and Review Technique (PERT) and Critical Path Method (CPM), were developed to help with project planning. PERT was introduced by the Special Projects Office of the United States Navy in 1958 as an aid in planning (and controlling) its Polaris Weapon System, a project that involved approximately 3,000 contractors. At virtually the same time, a similar technique, CPM, was introduced by the DuPont Company. The methods are very similar and essentially show the flow of activities from start to finish. Over the years, the two methods have essentially merged and people often refer to PERT/CPM diagrams and/or analysis. As project management computer software has become more sophisticated, other similar approaches have been developed that provide more accurate time estimates, but PERT and CPM are still traditionally used to introduce the basic network diagramming concepts (Dodin, 2006).

PERT/CPM diagrams allow the project manager to see the flow of tasks associated with a project by showing the interrelationships between activities. These diagrams allow the project manager to estimate the time necessary to complete the overall project given the interdependencies among tasks and to identify those critical points where a delay in task completion can have a major effect on overall project completion. In performing the PERT/CPM analysis, one assumes that all tasks or activities can be clearly identified and sequenced and that the time necessary for completing each task or activity can be estimated.

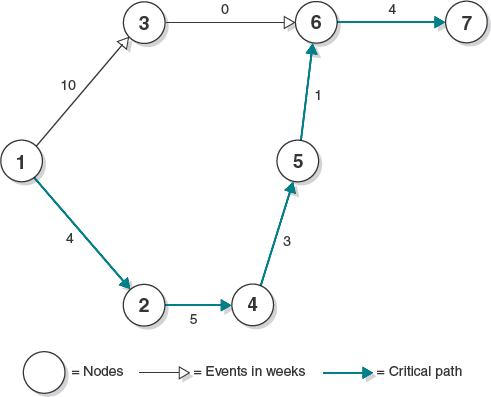

Figure M2.3 shows a simple PERT/CPM diagram. In the diagram, arrows designate activities. The circles at the beginning and end of the arrows are referred to as nodes; they designate starting and ending points for activities. These points in time, called events, consume no time in and of themselves. An activity is referred to as Activity i,j or Activity i-j, where i is the start node and j is the end node. Because of the way the diagram is constructed, the PERT/CPM diagram is sometimes referred to as an arrow or activity-on-arrow network diagram. Alternatively, activity-in-node network diagrams, as the name implies, place the activities within the node (usually drawn in boxes) and use the arrows simply to show the necessary ordering of activities. In activity-on-arrow diagrams the numbers along the arrows indicate the expected time for the activity to be completed. Although these numbers may come directly from the WBS, it is customary to calculate an expected time for activity completion (te), using a weighted average of an optimistic time (to), a pessimistic time (tp), and the most likely time (tm) using the following equation:

Note that Activity 3,6 has an expected time of zero weeks. This type of activity, called a dummy activity, is used to indicate that Activity 6,7 cannot begin until Activity 1,3 is complete.

The critical path is that chain of activities that takes the LONGEST time to proceed through the network. It indicates the least possible time in which the overall project can be completed, and it is the path that needs to be watched most carefully to ensure that the project stays "on track."

To identify the critical path, it is necessary to understand the concept of slack or float. In Figure M2.3, the critical path, 1-2-4-5-6-7, takes 17 weeks from start to finish. Note, however, that there is another path, 1-3-6-7, which only takes 14 weeks from start to finish. This means that Activity 1,3 could begin three weeks later than Activity 1,2 and the project would still be completed on time, assuming, of course, that the time estimates are fairly accurate. We then say that Activity 1,3 has a total float or slack of 3 weeks. While this is easy to see in Figure M2.3, it requires more effort when the diagram is more complex.

The first step in identifying the critical path is to identify the earliest start and finish times. Start at the first node of the diagram; this has an earliest start time of zero.

For the other nodes, the earliest start time equals the earliest finish time of the previous activity. For all activities, the earliest finish time is the sum of the earliest start time plus the estimated time of the activity.

Next, take the largest finish time for the last node and calculate the latest start and finish times by starting at the last node and subtracting the estimated time for completion of that activity from the latest finish time of the previous activity. To identify the critical path, make a list of latest finish times and earliest start times. Time available is then calculated as the difference between the earliest start time and the latest finish time. If available time is equal to the estimated time for completing the activity, there is no float, and that activity is on the critical path. Table M2.1 shows the calculations.

As indicated above, the critical path is important because it is that path that must be most closely monitored. It is the path for which there is no slack, and activities must begin and end on time in order for the project schedule to be met. Activities that are not on the critical path can begin any time between the earliest and latest start dates. The determination is usually made in accordance with the availability of resources, primarily human resources.

Because projects typically require trade-offs among cost, time, and quality, project managers often need to estimate different approaches to the project. Project-crashing analysis can be used to help estimate the trade-offs associated with expediting a particular project by reviewing the costs associated with reducing the amount of time to complete the tasks on the critical path by adding additional resources.

The ultimate purpose of project management is to obtain the most efficient use of resources while still achieving project objectives (being effective). Efficient use of resources can be a problem, however, if there are wide swings in resource needs. Even on carefully planned projects, there may be times when team members feel they can't get enough done as well as times when team members find they do not have enough to do (House, 1988).

Resource leveling is "the process of scheduling work on noncritical activities so that resource requirement on peak days will be reduced" (Kimmons, 1990, p. 79). Resources here refers to all project resources that are limited within a specified time period, including personnel, equipment, and materials; resource leveling is most often used to allocate personnel to different project activities. One approach to maximizing the use of people is to use the information from the WBS, together with the information regarding the amount of float, to schedule activities that are not on the critical path.

To determine the optimal use of resources, the project manager needs to begin by assuming that all activities will begin at their earliest start dates. Based on this assumption, the project manager can then draw a graph showing the required personnel, by job type (title), over time. This graph will show peaks, times when there is a great amount of work to be done, and valleys, times when there is less work to be done. Using the PERT/CPM diagram and the table that gives the float associated with each activity, the project manager can then level the resources by moving the start dates for some of the activities that have float to a later time (but prior to the latest start date). The process continues until the changes in personnel requirements from one time period to the next are minimized, that is, until the peaks and valleys are evened. Of course, this type of manual resource leveling is extremely difficult on large, complex projects. Fortunately, in 1986, the resource-leveling paradigm was revolutionized when Primavera Software, Inc. developed an automatic resource leveling tool (Nosbisch & Winter, 2006). Since that time, other automatic resource leveling tools have greatly improved the ability of project managers to deploy resources more efficiently.

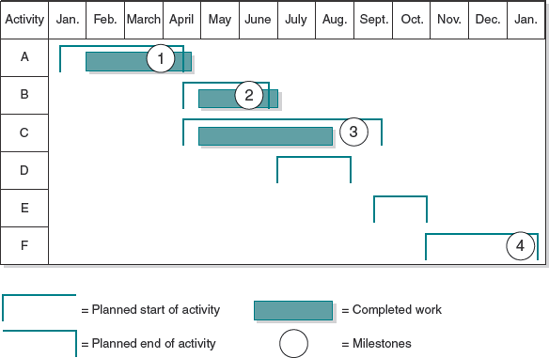

The most popular tool for visually displaying project activities across time is the Gantt chart, developed by Henry L. Gantt in the early part of the twentieth century. These charts are essentially bar charts that allow you to see at a glance how the different activities fit into the overall schedule.

A Gantt chart includes a timeline and a list of each of the major activities, grouped as they are in the work breakdown structure and sequenced as they are expected to occur as a result of the PERT/CPM and resource leveling analyses. The time line for the project is shown along the horizontal axis; the list of activities along the vertical axis. For each activity, a bar shows the time commitment (see Figure M2.4). The Gantt chart is most useful when each activity time is commensurate with the units of time drawn on the horizontal axis. That is, if the horizontal axis is drawn in terms of months, most activities should take at least two months. You can also identify specific milestones, or points of accomplishment, within each task by using a circled number within the bar. In Figure M2.4 the milestones could represent first drafts of status reports due at the end of the activity. While advanced project management software can be used to create Gantt charts, they can also be created in spreadsheet programs such as Microsoft Excel by using a stacked bar chart (Baltzan & Phillips, 2008).

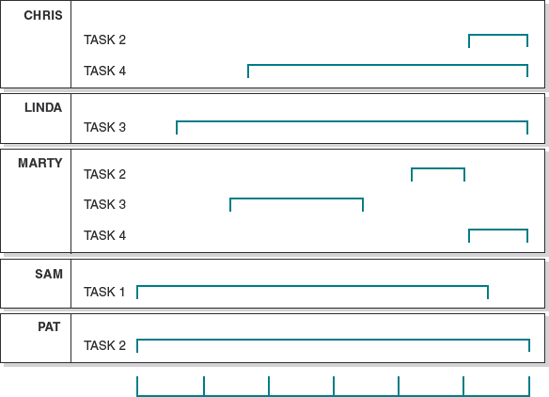

Specialized Gantt Charts. Once the Gantt chart is constructed, it can be used to integrate information about projected use of time with information about projected use of other resources. Two types of integrated Gantt charts are commonly used. The first shows personnel task assignments. By listing each individual along the vertical axis, followed by all of the tasks/activities to which that individual is assigned, the project manager can see at a glance which tasks/activities each person is assigned to at each time period of the project (see Figure M2.5). If the task distribution across individuals is uneven or if some individuals were mistakenly given too many work assignments during a single time period, this chart gives the project manager another chance to redistribute task assignments.

The second type of integrated Gantt chart is the Bar Chart Cost Schedule (not illustrated). This Gantt chart simply shows the projected cost of each activity below the bar showing that activity in the overall Gantt chart. This allows the project manager to have some sense of how much money is projected to be spent in each time period. It also allows the project manager to calculate the cost slope by dividing the cost of the activity by the duration of that activity (in whatever unit of time is being used). Thus, for example, if Activity A costs $4,500 and is expected to take three weeks to complete, the cost slope in dollars per week is $1,500. While this piece of information is not interesting in isolation, it becomes interesting when the project manager compares it to the cost slopes of other activities because it gives a sense of the relative cost of activities per time period.

Gantt Charts as Monitoring Tools. The Gantt chart is also a useful project monitoring tool. By using different colors or different symbols, the Gantt chart can help the project manager track how closely the project is keeping to the planned schedule. When a given task runs over the allotted time, the Gantt chart can be used to determine whether or not the schedule needs to be rethought. Figure M2.4 shows that Activities A and B ran over schedule approximately one week each, whereas Activity C was completed almost one month ahead of schedule.

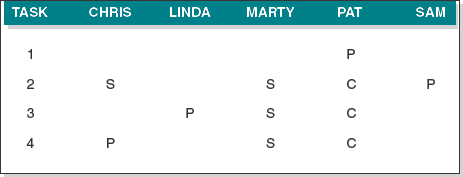

One final planning tool is the human resource matrix. As with the Gantt chart used to show the personnel task assignments, this matrix can be used to see whether workload is evenly distributed across individuals. The human resource matrix lists the tasks/activities along the vertical axis and the names across the top of the matrix (see Figure M2.6). For each task/activity one person is designated as having primary responsibility (P), and others may be designated as having secondary responsibility (S). Other designations can be also be added as needed. For example, one can label an individual as (C) if that individual needs to be consulted, or (B) if a person can provide backup, and so on. Project teams need to be able to adapt the project management tools to best meet their needs.

One advantage of this chart over the personnel task assignment chart is that it is clear whether or not time spent on the project is time in a leadership capacity. Further, it makes it clear at a glance whether someone has too many leadership (primary) assignments. Alternatively, while it tells who is assigned to which task/activity, it is not as informative as the personnel task assignment chart with respect to how much time is being spent during each time period by each person. Therefore, it is probably wise to use the two charts together for keeping track of how human resources are being utilized.

As indicated in the beginning of this section, monitoring is essentially keeping track of progress over the life of the project. There are four primary resources that need to be monitored: time, money, people, and materials. Monitoring involves looking at actual expenditures of resources, comparing actual with estimated, and, where necessary, deciding what adjustments need to be made in the work plan to accommodate discrepancies between actual and estimated.

In the previous section, we gave examples of planning tools that can be used in monitoring the use of human resources and time. Here we will focus on the project budget and time. Note that the tools provided here can be used to look at the total budget or at specific components of the budget, and so they are applicable to monitoring the use of human resources and materials as well.

Cost Variances. In monitoring the budget, the project manager is concerned with two types of information. The first involves the amount of money budgeted for the work to be performed (budgeted cost of work performed—BCWP) versus the actual cost of performing the work (actual cost of work performed—ACWP). The difference between the two quantities (BCWP—ACWP), called the cost variance, is an indication of how close the estimated costs were to actual costs, with a positive number indicating monetary savings and a negative number indicating a budget overrun. (Again, note that these variances can be calculated for the total budget or by category of expenditure.)

Schedule Variances. The second type of information involves the amount of money projected to be spent on the actual work performed during the time period (budgeted cost of work performed—BCWP) versus the amount scheduled to be spent during the time period (budgeted cost of work scheduled—BCWS). The difference between the two quantities (BCWP—BCWS), called the schedule variance, is an indication of whether the money is being spent according to the projected schedule. Here a positive number is an indication that the project is running ahead of schedule—that is, more work is being performed than was originally scheduled—whereas a negative number is an indication that the project is running behind schedule—less work is being performed than was actually scheduled. Alternatively, a negative number could be an indication that some work is being performed out of its scheduled sequence. Harrison (1992) suggests that schedule variance should not be looked at separately from the formal scheduling system; that is, this information should be examined in conjunction with the Gantt chart or PERT/CPM network diagram to determine the actual status of specific activities or milestones.

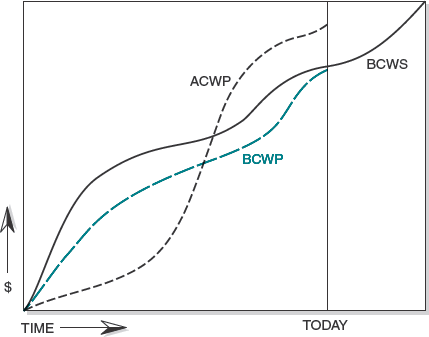

Cost and schedule variances can be examined graphically or in a table. To examine these variances graphically, the project manager needs to calculate at each time period a cumulative BCWS, BCWP, and ACWP. That is, for each reporting period (usually monthly) the project manager needs to calculate the total scheduled budget up to that time period (cumulative BCWS), the total projected budget for the work that has actually been performed up to that time period (cumulative BCWP), and the total budget actually spent up to that time period (cumulative ACWP). The three amounts are plotted at each time period along the vertical axis, with time across the horizontal axis. The points are then connected to make a smooth curve (see Figure M2.7). Note that the cumulative BCWS curve extends from the lower-left corner, where no money has been budgeted to be spent before the beginning of the project, to the upper-right corner, where all the money is budgeted to be spent by the end of the project. When the cumulative BCWP curve lies above the cumulative ACWP curve, then the project is running under budget. Alternatively, if the cumulative ACWP lies above the cumulative BCWP curve, the project is running over budget, and the project manager needs to understand why. Similarly, if the cumulative BCWS lies below the BCWP, then the project may well be running ahead of schedule. Alternatively, if the BCWS lies above the BCWP, then the amount that the project manager expected to spend up to that time period is less than the amount actually being spent, and the project may be behind schedule. In Figure M2.7, the project was initially running under budget but is now running considerably over budget. It was also initially behind schedule, but is catching up.

A performance analysis report presents cost and schedule variance in a tabular form. This report is usually generated on a monthly basis, although, depending on the complexity of the project, it could be done more or less often. The report includes two tables, one with information about performance in the current time period and the second with information about cumulative performance. The first table presents five pieces of information for each category of expenditure: the amount budgeted for this time period (BCWS), the amount budgeted for the work performed (BCWP), the amount actually spent in the current time period (ACWP), and the schedule and cost variance. The second table repeats this format, providing cumulative information.

Again, the project manager should be concerned when the performance analysis report indicates negative cost or schedule variances. In some cases, project variances may be related to scope creep—the expansion of the project requirements beyond the original plan due to small changes that are made over the course of time. Those seemingly small changes can add up to big differences in the scope of a project, so keeping track of them is essential. In some cases, it may be appropriate to renegotiate the terms of the project, so it is critical for project managers to have solid data to justify any request for changes in resource allocations or deadlines.

Objective | This exercise asks you to analyze the tasks in a project using the tools that we have discussed. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||