2

Introduction to Behavioral Biases

Nothing in life is quite as important as you think it is while you're thinking about it.

—Daniel Kahneman

Introduction

In order to create your best portfolio, it is essential that you obtain an understanding of the irrational behaviors that you have—or be able to recognize the biases of others that may be involved in your investment decision-making process. Numerous research studies have shown that when people are faced with complex decision-making problems that demand substantial time and cognitive decision-making requirements, they have difficulty devising a rational approach to developing and analyzing a proper course of action. This problem is exacerbated by the fact that many consumers need to contend with a potential overload of information to process. Have you walked down the shampoo aisle lately? Way too many choices—how do you pick? And this is one of the easier decisions we face! When it comes to our money, it becomes even more complicated. For more meaningful decisions, people don't systematically describe problems, record necessary data, and/or synthesize information to create rules for making decisions, which is really the best way to make complex decisions. Instead, people usually follow a more subjective path of reasoning to determine a course of action consistent with their desired outcome or general preferences.

Individuals make decisions, although typically suboptimal ones, by simplifying the choices presented to them, typically using a subset of the information available, and discarding some (usually complicated but potentially good) alternatives to get down to a more manageable number. They are content to find a solution that is “good enough” rather than arriving at the optimal decision. In doing so, they may (unintentionally) bias the decision-making process. These biases may lead to irrational behaviors and flawed decisions. In the investment realm, this happens a lot; many researchers have documented numerous biases that investors have. This chapter will introduce these biases, which we will review in the coming chapters, and highlight the importance of understanding them and dealing with them before they have a chance to negatively impact the investment decision-making process.

Behavioral Biases Defined

The dictionary defines a “bias” in several different ways, including: (a) a statistical sampling or testing error caused by systematically favoring some outcomes over others; (b) a preference or an inclination, especially one that inhibits impartial judgment; (c) an inclination or prejudice in favor of a particular viewpoint; and (d) an inclination of temperament or outlook, especially, a personal and sometimes unreasoned judgment. In this book, we are naturally concerned with biases that cause irrational financial decisions due to either: (1) faulty cognitive reasoning or (2) reasoning influenced by emotions, which can also be considered feelings, or, unfortunately, due to both. The first dictionary definition (a) of bias is consistent with faulty cognitive reasoning or thinking, while (b), (c), and (d) are more consistent with impaired reasoning influenced by feelings or emotion.

Behavioral biases are defined, essentially, the same way as systematic errors in judgment. Researchers distinguish a long list of specific biases and have applied over 100 of these to individual investor behaviors in recent studies. When one considers the derivative and the undiscovered biases awaiting application in personal finance, the list of systematic investor errors seems very long indeed. More brilliant research seeks to categorize these biases according to a meaningful framework. Some authors refer to biases as heuristics (rules of thumb), while others call them beliefs, judgments, or preferences. Psychologists' factors include cognitive information processing shortcuts or heuristics, memory errors, emotional and/or motivational factors, and social influences such as family upbringing or societal culture. Some biases identified by psychologists are understood in relation to human needs such as those identified by Maslow—physiological, safety, social, esteem, and self-actualizing. In satisfying these needs, people will generally attempt to avoid pain and seek pleasure. The avoidance of pain can be as subtle as refusing to acknowledge mistakes in order to maintain a positive self-image. The biases that help to avoid pain and instead produce pleasure may be classified as emotional. Other biases are attributed by psychologists to the particular way the brain perceives, forms memories, and makes judgments; the inability to do complex mathematical calculations, such as updating probabilities; and the processing and filtering of information.

This sort of bias taxonomy is helpful as an underlying theory about why and how people operate under bias, but no universal theory has been developed (yet). Instead of a universal theory of investment behavior, behavioral finance research relies on a broad collection of evidence pointing to the ineffectiveness of human decision making in various economic decision-making circumstances.

Why Understanding and Identifying Behavioral Biases Is Crucial

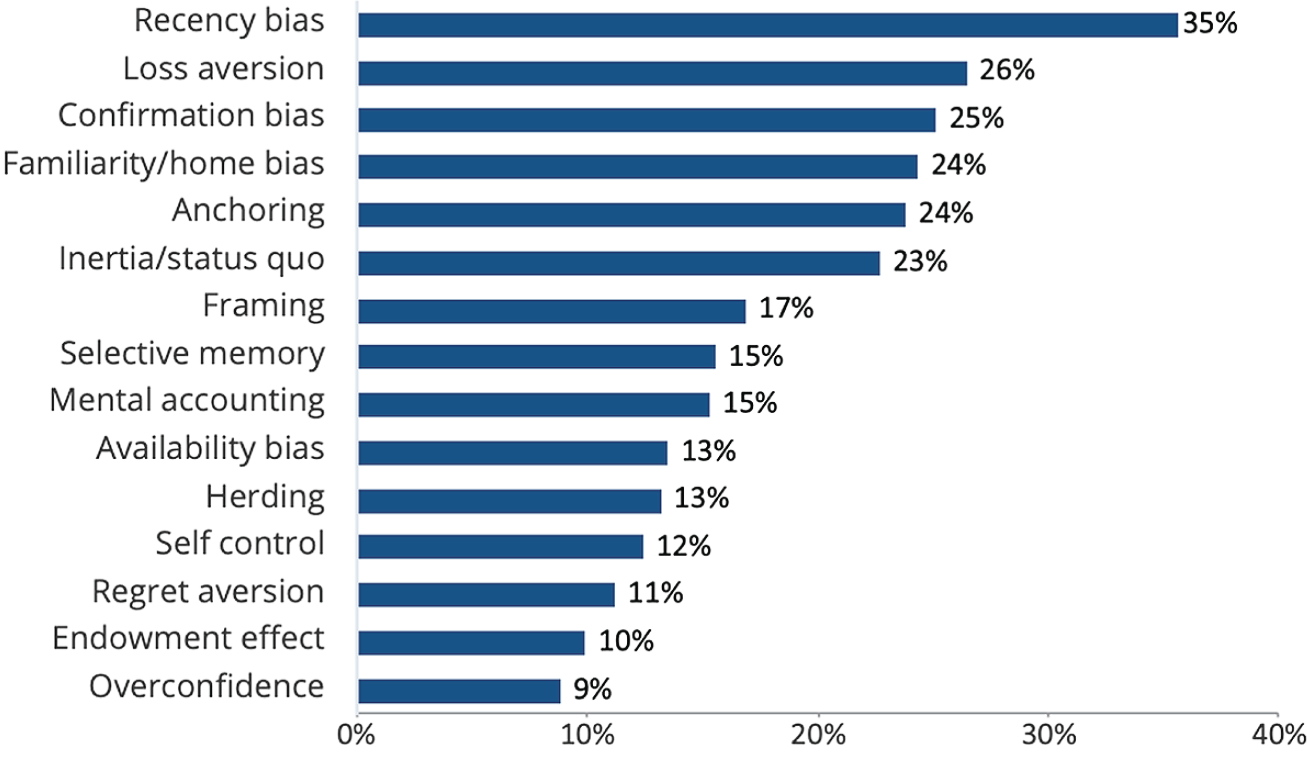

By understanding the effects that behavioral biases have on the investment process, investors may be able to significantly improve their economic outcomes and attain stated financial objectives. As noted in Chapter 1, during my 30+ year career advising clients, I have found that recognizing and managing the most frequently occurring behavioral biases is crucial to obtaining financial success. For many years I have had my “Top 3” most common behavioral biases—Loss Aversion, Confirmation and Recency biases. Coincidentally, a recent study by Charles Schwab confirms my Top 3, albeit in a slightly different order as can be seen in Figure 2.1 which illustrates how often financial advisors see each bias in the clients they serve. If you are short on time, and you want to only review the most common biases, skip ahead to the chapters containing Loss Aversion, Confirmation, and Recency biases.

Figure 2.1 Most Significant Behavioral Biases Affecting Client Investment Decisions 2019

Source: Charles Schwab

In my experience, simply identifying a behavioral bias at the right time can save investors from potential financial disaster. During my 30+, spanning numerous economic meltdowns, including but not limited to 1987 (my first year in the business), 1998, 2001, 2008–2009, 2018, and 2020, I've talked many of my clients “down from the ledge” and out of selling their risky assets at the wrong time due to irrational panic behavior. In fact, many of my long-time clients are now used to volatility and do not panic. They look at market drops as buying opportunities. This behavior-modifying advice has helped investors to reach their financial goals. In other cases, I was able to identify a behavioral bias or a group of biases and decided to adapt to the biased behavior so that overall financial decisions improved and the most appropriate portfolios were built—that is, one the investors could stick to over time. It is crucial for you to understand how you make decision to build the best portfolio for you. For example, some investors have a gambling instinct, or want to take risks with some of their capital. My advice in many of these cases is to carve out a small percentage of the portfolio for risky bets, leaving the vast majority of wealth in a prudent, well-organized portfolio. In short, knowledge of the biases reviewed in this book and the modification of or adaption to irrational behavior may lead to superior results.

How to Identify Behavioral Biases

Biases can be diagnosed by means of a specific series of questions. In this book, Chapters 3 through 22 contain a list of diagnostic questions to determine susceptibility to each bias. In addition, a case-study approach is used to illustrate susceptibility to biases is given with advice on how to build portfolios. In either case, investors who wish to incorporate behavioral analysis into their portfolio management practices will need to administer diagnostic “tests” with utmost discretion, especially at the outset of a relationship. When one becomes very good at diagnosing irrational behavior, it can be done without fanfare or much notice. As one gets to know their biases, better portfolio outcomes are the result.

Categorization of Behavioral Biases

In its simplest form, cognitive biases are those biases based on faulty cognitive reasoning (cognitive errors), while emotional biases are those based on reasoning influenced by feelings or emotions. Cognitive errors stem from basic statistical, information processing, or memory errors; cognitive errors may be considered to be the result of faulty reasoning. Emotional biases stem from impulse or intuition; emotional biases may be considered to result from reasoning influenced by feelings. Behavioral biases, regardless of source, may cause decisions to deviate from the assumed rational decisions of traditional finance. A more elaborate distinction between cognitive and emotional biases is made in the next section.

Differences between Cognitive and Emotional Biases

In this book, behavioral biases are classified as either cognitive or emotional biases, not only because the distinction is straightforward but also because the cognitive-emotional breakdown provides a useful framework for understanding how to effectively deal with them in practice. I recommend thinking about investment decision making as occurring along a (somewhat unrealistic) spectrum from the completely rational decision making of traditional finance to purely emotional decision making. In that context, cognitive biases are basic statistical, information processing, or memory errors that cause the decision to deviate from rationality. Emotional biases are those that arise spontaneously as a result of attitudes and feelings and that cause the decision to deviate from the rational decisions of traditional finance.

Cognitive errors, which stem from basic statistical, information processing, or memory errors, are more easily corrected for than are emotional biases. Why? Investors are better able to adapt their behaviors or modify their processes if the source of the bias is illogical reasoning, even if the investor does not fully understand the investment issues under consideration. For example, an individual may not understand the complex mathematical process used to create a correlation table of asset classes, but he can understand that the process he is using to create a portfolio of uncorrelated investments is best. In other situations, cognitive biases can be thought of as “blind spots” or distortions in the human mind. Cognitive biases do not result from emotional or intellectual predispositions toward certain judgments, but rather from subconscious mental procedures for processing information. In general, because cognitive errors stem from faulty reasoning, better information, education, and advice can often correct for them.

Difference among Cognitive Biases

In this book, we review 13 cognitive biases, their implications for financial decision making, and suggestions for correcting for the biases. As previously mentioned, cognitive errors are statistical, information processing, or memory errors—a somewhat broad description. An individual may be attempting to follow a rational decision-making process but fails to do so because of cognitive errors. For example, they may fail to update probabilities correctly, to properly weigh and consider information, or to gather information. If corrected by supplemental or educational information, an individual attempting to follow a rational decision-making process may be receptive to correcting the errors.

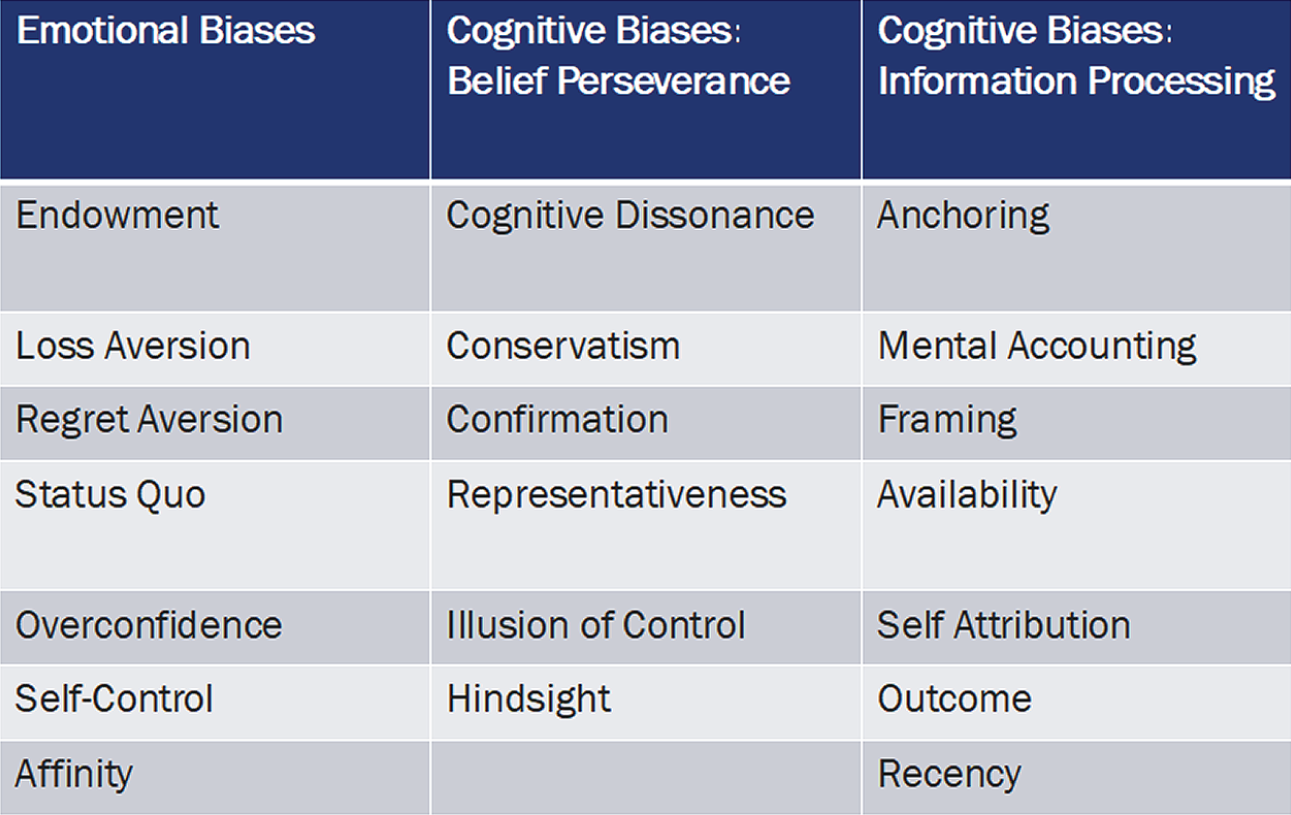

To make things simpler, I have identified and classified cognitive biases into two categories. The first category contains “belief perseverance” biases. In general, belief perseverance may be thought of as the tendency to cling to one's previously held beliefs irrationally or illogically. The belief continues to be held and justified by committing statistical, information processing, or memory errors.

Belief Perseverance Biases

Belief perseverance biases are closely related to the psychological concept of cognitive dissonance, a bias I will review in the next chapter. Cognitive dissonance is the mental discomfort that one feels when new information conflicts with previously held beliefs or cognitions. To resolve this discomfort, people tend to notice only information of interest to them (called selective exposure), ignore or modify information that conflicts with existing beliefs (called selective perception), and/or remember and consider only information that confirms existing beliefs (called selective retention). Aspects of these behaviors are contained in the biases categorized as belief perseverance. The six belief perseverance biases covered in this book are: cognitive dissonance, conservatism, confirmation, representativeness, illusion of control, and hindsight.

Information-Processing Biases

The second category of cognitive biases has to do with “processing errors,” and describes how information may be processed and used illogically or irrationally in financial decision making. As opposed to belief perseverance biases, these are less related to errors of memory or in assigning and updating probabilities and instead have more to do with how information is processed. The seven processing errors discussed are: anchoring and adjustment, mental accounting, framing, availability, self-attribution bias, outcome bias, and recency bias.

Individuals are less likely to make cognitive errors if they remain vigilant to the possibility that they may occur. A systematic process to describe problems and objectives; to gather, record, and synthesize information; to document decisions and the reasoning behind them; and to compare the actual outcomes with expected results will help reduce cognitive errors.

Emotional Biases

Although emotion has no single universally accepted definition, it is generally agreed upon that an emotion is a mental state that arises spontaneously rather than through conscious effort. Emotions are related to feelings, perceptions, or beliefs about elements, objects, or relations between them; these can be a function of reality or the imagination. Emotions may result in physical manifestations, often involuntary. Emotions can cause investors to make suboptimal decisions. Emotions may be unwanted by the individuals feeling them, and while they may wish to control the emotion and their response to it, they often cannot.

Emotional biases are harder to correct for than cognitive errors because they originate from impulse or intuition rather than conscious calculations. In other words, a bias that is an inclination of temperament or outlook, especially a personal and sometimes unreasonable judgment, is harder to correct. When investors adapt to a bias, they accept it and make decisions that recognize and adjust for it rather than making an attempt to reduce it. To moderate the impact of a bias is to recognize it and to attempt to reduce or even eliminate it within the individual rather than to accept the bias. In the case of emotional biases, it may be possible to only recognize the bias and adapt to it rather than correct for it.

Emotional biases stem from impulse, intuition, and feelings and may result in personal and unreasoned decisions. When possible, focusing on cognitive aspects of the biases may be more effective than trying to alter an emotional response. Also, educating the investors about the investment decision-making process and portfolio theory can be helpful in moving the decision making from an emotional basis to a cognitive basis. When biases are emotional in nature, drawing them to the attention of the individual making the decision is unlikely to lead to positive outcomes. The individual is likely to become defensive rather than receptive to considering alternatives. Thinking of the appropriate questions to ask and to focus on as well as potentially altering the decision-making process are likely to be the most effective options.

Emotional biases can cause investors to make suboptimal decisions. The emotional biases are rarely identified and recorded in the decision-making process because they have to do with how people feel rather than what and how they think. The six emotional biases discussed are: loss aversion, overconfidence, self-control, status quo, endowment, and regret aversion. In the discussion of each of these biases, some related biases may be discussed.

Figure 2.2 Categorization of Twenty Behavioral Biases

Figure 2.2 below is a roadmap for the 20 biases that you will be seeing in the upcoming chapters.

A Final Word on Biases

The cognitive-emotional distinction will help us determine when and how to adjust for behavioral biases in financial decision making. However, it should be noted that specific biases may have some common aspects and that a specific bias may seem to have both cognitive and emotional aspects. Researchers in financial decision making have identified numerous and specific behavioral biases. This book will not attempt to discuss all identified biases but rather will discuss what I consider to be the most important biases within the cognitive-emotional framework for considering potential biases. This framework will be useful in developing an awareness of biases, their implications, and ways of moderating their impact or adapting to them. The intent is to help investors and their advisors to have a heightened awareness of biases so that financial decisions and resulting economic outcomes are potentially improved.