16

Emotional Bias #1: Loss Aversion Bias

Win as if you were used to it, lose as if you enjoyed it for a change.

—Ralph Waldo Emerson

Bias Description

Bias Name: Loss aversion bias

Bias type: Emotional

General Description

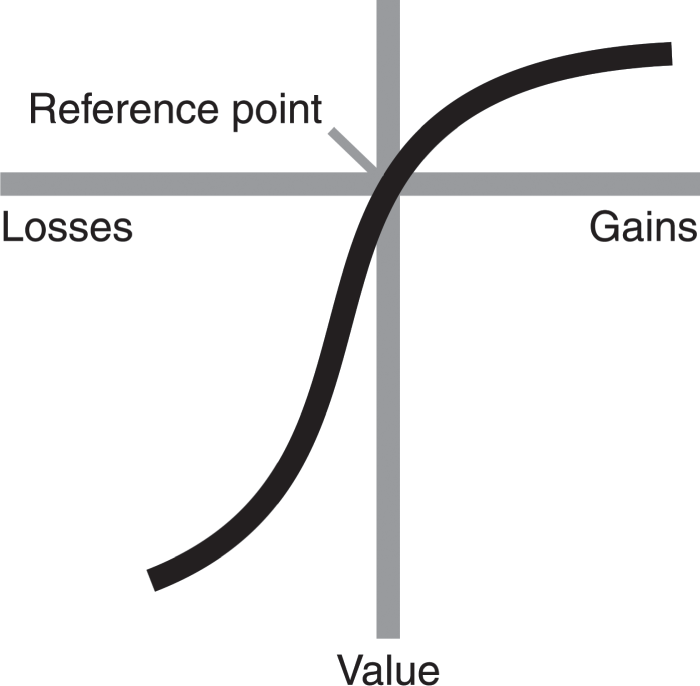

Loss aversion bias was developed by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky in 1979, as part of the original prospect theory,1 specifically in response to prospect theory's observation that people generally feel a stronger impulse to avoid losses than to acquire gains. A number of studies on loss aversion have given birth to a common rule of thumb: psychologically, the possibility of a loss is on average twice as powerful a motivator as the possibility of making a gain of equal magnitude; that is, a loss-averse person might demand, at minimum, a $2 gain for every $1 placed at risk. In this scenario, risks that don't “pay double” are unacceptable.

Loss aversion can prevent people from unloading unprofitable investments, even when they see little to no prospect of a turnaround. Some industry veterans have coined a diagnosis of “get-even-itis” to describe this widespread affliction, whereby a person waits too long for an investment to rebound following a loss. Get-even-itis can be dangerous because, often, the best response to a loss is to sell the offending security and to redeploy those assets. Similarly, loss aversion bias can make investors dwell excessively on risk avoidance when evaluating possible gains, since dodging a loss is a more urgent concern than seeking a profit. When their investments do begin to succeed, loss-averse individuals hasten to lock in profits, fearing that, otherwise, the market might reverse itself and rescind their returns. The problem here is that divesting prematurely to protect gains limits upside potential. In sum, loss aversion causes investors to hold their losing investments and to sell their winning ones, leading to suboptimal portfolio returns.

Example of Loss Aversion Bias

Loss aversion bias is one of the most common behavioral biases. Investors open up the monthly statements prepared by their advisors, skim columns of numbers, and usually notice both winners and losers. In classic cases of loss aversion, investors dread selling the securities that haven't performed well. Get-even-itis takes hold, and the instinct is to hold onto a losing investment until, at the very least, it rebounds enough for the investor to break even. Often, however, research into a losing investment would reveal a company whose prospects don't forecast a rebound. Continuing to hold stock in that company actually adds risk to an investor's portfolio (hence, the investor's behavior is risk seeking, which accords with the path of the value function in Figure 16.1).

Conversely, when the monthly statement indicates that profits are being made, the loss-averse investor is gripped by a powerful urge to “take the money and run,” rather than to assume continued risk. Of course, frequently, holding on to a winning stock isn't a risky proposition if the company is performing well; that is, profitable investments that the loss-averse investor wants to sell might actually be improving the portfolio's risk–return profile. Therefore, selling deteriorates that risk–return profile and eliminates the potential for further gains. When the increased risks associated with holding on to losing investments are considered in combination with the prospect of losing future gains that occur when selling winners, the degree of overall harm that a loss-averse investor can suffer begins to become clear.

Figure 16.1 The Value Function—A Key Tenet of Prospect Theory

Source: The Econometric Society

A final thought on taking losses: Some investors, remarking on losing investments that haven't yet been sold, rationalize that “It's only a paper loss.” In one sense, yes, this is true. Inasmuch as the investment is still held, a loss has technically not been triggered for tax purposes.

In reality, though, this kind of rationale covers up the fact that a loss has taken place. If you went to the market to sell, having just incurred a “paper loss,” the price you would obtain for your investment would be lower than the price you paid—effecting a very “real” loss indeed. Thus, if holding on to a losing investment does not objectively enhance the likelihood of recouping a loss, then it is better to simply realize the loss, get the tax benefit, and move on.

Implications for Investors

Loss aversion is a bias that simply cannot be tolerated in financial decision making. It instigates the exact opposite of what investors want: increased risk, with lower returns. Investors should take risk to increase gains, not to mitigate losses. Holding losers and selling winners will wreak havoc on a portfolio. Box 16.1 summarizes some common investment mistakes linked to loss aversion bias.

Am I Subject to Loss Aversion Bias?

These questions are designed to detect signs of emotional bias stemming from loss aversion. To complete the test, select the answer choice that best characterizes your response to each item.

Loss Aversion Bias Test

Question 1: Suppose you make a plan to invest $50,000. You are presented with two alternatives. Which scenario would you rather have?

- Be assured that I'll get back my $50,000, at the very least—even if I don't make any more money.

- Have a 50 percent chance of getting $70,000 and a 50 percent chance of getting $35,000.

Question 2: Suppose you make a plan to invest $70,000. You are presented with two alternatives. Which scenario would you rather have?

- Know that I'll be repaid only $60,000, for sure.

- Take a 50–50 gamble, knowing that I'll get back either $75,000 or $50,000.

Question 3: Choose one of these two outcomes:

- An assured gain of $475.

- A 25 percent chance of gaining $2,000 and a 75 percent chance of gaining nothing.

Question 4: Choose one of these two outcomes:

- An assured loss of $725.

- A 75 percent chance of losing $1,000 and a 25 percent chance of losing nothing.

Test Results Analysis

Question 1: People who are loss averse are most likely to select “a,” even though “b” offers a larger potential return on the upside.

Question 2: Increased initial endowment aside, this is basically the same question as Question 1. Most people, however, would probably select “b,” because most people tend to be loss averse. Loss-averse investors are willing to gamble and risk an even greater loss rather than to admit a loss (“a”). However, this isn't simply a matter of an unconditional penchant for gambling. Most investors (that is, loss-averse investors) prefer the assurance of breaking even over the opportunity to gain a profit in Question 1.

Question 3: The rational response is “b,” but loss-averse investors are likely to opt for the assurance of a profit in “a.”

Question 4: The rational response is “a.” Loss-averse investors are more likely to select “b.”

Investment Advice

Box 16.1 listed some errors that investors often commit when they are subject to loss-aversion bias. These corresponding strategies can be employed by investors who want to attempt to moderate loss aversion.

Get-even-itis. Beware: Holding losing stocks for too long is harmful to your investment health. One symptom of get-even-itis is that an investor's decision making regarding some investments seems to be dependent on the original price paid for that investment. One effective remedy is a stop-loss rule. You may, for example, agree to sell a security immediately if it ever incurs a 10 percent loss. However, it's best to consider an investment's normal, expected levels of volatility when devising a stop-loss rule. You don't want to be forced to sell if an investment's price is just exhibiting its customary ups and downs.

Take the money and run. Loss aversion can cause investors to sell winning positions too early, fearing that that their profits will evaporate otherwise. This behavior limits the upside potential of a portfolio and can lead to overtrading (which also reduces returns). Just as stop-loss rules can help to combat get-even-itis, it is often helpful to institute rules for selling appreciating investments. As with stop-loss rules, price-appreciation rules work best when tailored to reflect details related to fundamentals and valuation. The goal is to let gains run. Remember too that, in a taxable account, you should avoid paying taxes on appreciations as long as possible.

Taking on excessive risk. Loss aversion can cause investors to hold onto losing investments even in companies that are in serious trouble. In such a case, it may be helpful to educate investors about an investment's risk profile—taking time to evaluate items such as standard deviation, credit rating, buy/sell/hold ratings, and so on. The investor will then, hopefully, make the right decision to protect the overall portfolio and jettison the risky, poorly performing investment.

Unbalanced portfolios. Loss aversion can cause investors to hold unbalanced portfolios. Education about the benefits of asset allocation and diversification is critical, yet it may be insufficient if an investor holds a concentrated stock position with emotional strings attached. A useful question in this situation is: “If you didn't own any XYZ stock today, would you still want to pick up as many shares as you own right now?” If and when the answer is “no,” some leeway for maneuvering emerges. Tax considerations, such as low-cost basis, sometimes factor in, but certain strategies can be employed to manage this cost.

Note

- 1 Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, “Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk,” Econometrica 47 (1979): 263–291.