23

Staying on Target to Reach Financial Goals Is Hard

I'd like to live as a poor man, with lots of money.

—Pablo Picasso

When people have a big overarching financial goal that they are working towards there is no chance for immediate gratification. A long-term financial plan is something that's not going to be completed for a long time. That time is probably measured in years, or even in decades. And humans are not exactly patient. With the ups and downs of life and the volatility of the markets, the scale of years or decades is difficult to process and it's pretty easy to lose touch with your long-term financial goal. And if things don't get off to a great start, it may be very easy to just lose faith and potentially walk away or completely give up. Like reaching most goals, it's a one step at a time, one day at a time, one week at a time, etc. process. You can do it!

Intuitively most people know that saving money is a good thing but the desire for material goods and spending on services often overrides otherwise good instincts. Understanding why behavior is so difficult to control is actually quite simple—a lack of self-discipline driven by psychological and/or environmental factors—but solutions are often complex and illusory. In this chapter we start by examining some simple examples of self-defeating behavior, two of which are non-financial and three of which are financial examples. By doing so we can get a common understanding of the challenges of controlling behavior and emphasize the importance of why behavior must be carefully managed.

Non-Financial Examples of Self-Defeating Behavior

In order to get a clearer understanding of self-defeating behavior in the financial realm, it can be helpful to see examples of non-financial self-defeating behavior. The following examples are intended to be generic and purposefully not meant to bring negative light to anyone matching this description.

Example 1: The Yo-Yo Dieter

Everyone knows someone who is overweight and has tried on numerous occasions to lose weight but has not been successful. I'm not talking about the rare individual with such a severe problem that gastric bypass surgery or other drastic measure is needed, but rather the person who is 30 to 50 to 100 pounds overweight and systematically fails at weight loss. And I'm also not talking about the uneducated person who does not know the number of calories contained in food or the unhealthy effects of carrying around extra kilos. The people I am considering know that what they are putting into their bodies is what is making them overweight.

These unfortunate folks have often been traveling on a “yo-yo” or riding on a rollercoaster of diets—losing pounds then gaining pounds, gaining then losing, and back again. Through the dieting process, these people get educated on the calorie count of food and, by doing so, consciously know how much extra food is going into their bodies in terms of calories they eat per day. They also know that they don't eat enough fruits and vegetables (or none at all) or exercise enough (or not at all). Attempts at a “quick fix” are therefore attractive, however unsustainable these types of diet may be. We've all heard about diets such as all meat or no meat, or a host of others that work for a while but eventually fail as the “old behaviors” and the accompanying pounds come back. At some point these people just “give up” and say to themselves that they “can't do it” and go on with life with the extra pounds. There are a number of psychological and physiological reasons for overeating. Although the following list1 is targeted at women, and may not be completely exhaustive, it contains some key reasons why people overeat (and much of the information is applicable to men as well):

- Boredom—You eat when you're bored or do not have anything interesting to do or to look forward to. TV is a favorite pastime especially when you are alone at home and bored. When food commercials are running 200 images per hour into our cerebral cortex it is difficult not to be drawn toward the refrigerator. If food commercials are a trigger, watch nature shows or commercial-free TV.

- Feeling Deprived—You feel deprived of the foods you enjoy, which leaves you craving for them even more. Media's attitude toward emphasizing thinness as the ideal has led to restrictive dieting and avoidance of entire groups of foods. Unfortunately, because the foods we are urged to avoid are abundantly available, and food visibility and availability are powerful eating stimuli, restrictors often break the “plan” and eat forbidden foods. Once this happens, overwhelming guilt, followed by feelings of low self-esteem, motivate the individual to go on over-consuming the avoided food in an attempt to numb these negative feelings.

- Glucose intolerance—This is a physiological trigger. In a healthy body, carbohydrates are converted to glucose and a blood glucose level of ~60–120 mg/dl is maintained without thought to the dietary consumption of carbohydrate. In the glucose-intolerant population, carbohydrates are readily converted to glucose and the pancreas responds to this shift in blood sugar by secreting an excessive amount of the hormone, insulin. Insulin's job is to remove the glucose from the blood stream and help it to enter the body cells. If done properly, the blood glucose level returns to the normal range regardless of the amount of carbohydrates consumed. If this system is not working correctly, a quick rise in blood glucose occurs, followed by an over-production of insulin. The excessive insulin is not recognized by the body cells so it is unable to remove the glucose from the blood stream. The result is an increase in blood insulin levels, which has an appetite-stimulating effect. The person is driven to eat and, if simple carbohydrates are chosen, the cycle continues.

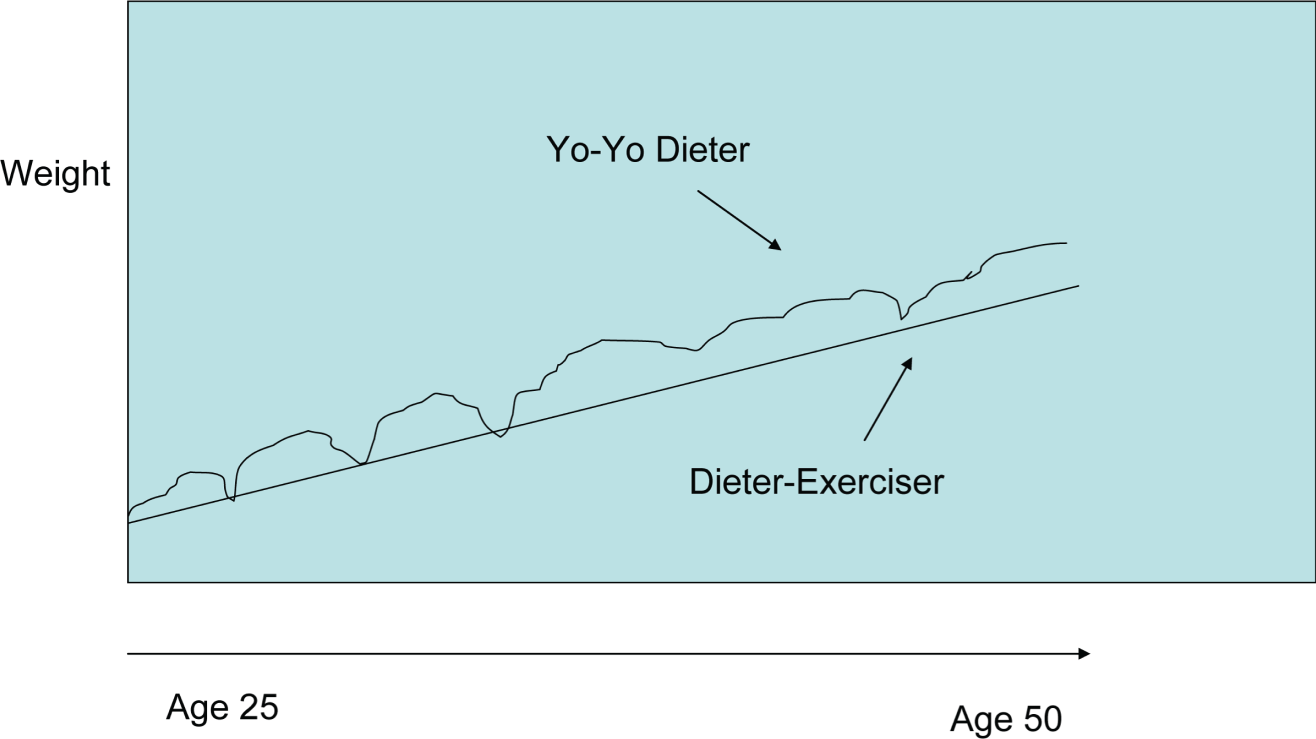

Figure 23.1 The Dieter-Exerciser versus the Yo-Yo Dieter

Other factors include a lifestyle that is constantly draining your energy, a desire for comfort, feelings of being overwhelmed, upset or hurt, and the big one—a lack of will power. Whatever the case, the basic facts are that there are too many people out there who know what they need to do to cut weight but cannot find the behavioral tools to succeed. This, naturally, is in contrast to the “dieter-exerciser” who eats right and exercises regularly and manages to get weight under control. It should be simple, right? For the record, I am a few pounds overweight myself and am guilty of several of the behaviors mentioned here … but the difference is that I am doing something about it. Because I realize I am in control of my diet and exercise and not the other way round. The following figure illustrates that as we age our weight is destined to go up (there are those who manage to keep it off their whole lives but not that many!) but if we can keep to a healthy diet and exercise, we will likely keep a more even weight gain and, if we do, we will likely weigh less than those who are on the roller coaster. Easier said than done! Figure 23.1 compares the Yo-Yo dieter to the Dieter-Exerciser.

Example 2: The Educated Smoker

Have you ever met a doctor or other health professional who is also a smoker? This one sort of astounds me. How can it be that a person who has devoted their lives to the health and well-being of others can treat their own body so carelessly? I can remember as a teenager, I would play sports with my friends in my backyard and witness my next-door neighbor, a doctor, chain-smoking on her porch. I knew even at that age the health risks of smoking and could not understand for the life of me why she smoked (I knew she had to know the risks involved.) Later, in her forties, I heard she died of lung cancer. This shocked me, but when I thought about it, I realized it shouldn't have come as a surprise. To this day, I still remember a poster in the hall of my middle school of an elderly, wrinkled, lifeless person holding a cigarette with the caption “Smoking is very debonair” across the bottom—which was meant to deter youngsters from smoking; it was shock treatment at an early age—and it worked. So how is it that a well-trained doctor, with full knowledge of the health risks of smoking, chain-smokes him- or herself to an almost certain death? As with the yo-yo dieter, there are psychological, as well as physiological, reasons why people who know smoking is bad still engage in the act. To name a few:2

For many people, smoking is a reliable lifestyle coping tool. Although every person's specific reasons to smoke are unique, they all share a common theme. Smoking is used as a way to suppress uncomfortable feelings, and smoking is used to alleviate stress, calm nerves, and relax. No wonder that when you are deprived of smoking, your mind and body are unsettled for a little while. Below is a list of some positive intentions often associated with smoking.

- Coping with anger, stress, anxiety, tiredness, or sadness

- Smoking is pleasant and relaxing

- Smoking is stimulating

- Acceptance—being part of a group

- As a way to socialize

- Provides support when things go wrong

- A way to look confident and in control

- Keeps weight down

- Rebellion—defining self as different or unique from a group

- A reminder to breathe

- Something to do with your mouth and hands

- Shutting out stimuli from the outside world

- Shutting out emotions from the inside world

- Something to do just for you and nobody else

- A way to shift gears or change states

- A way to feel confident

- A way to shut off distressing feelings

- A way to deal with stress or anxiety

- A way to get attention

- Marking the beginning or the end of something

The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) reports that people suffering from nicotine withdrawal have increased aggression, anxiety, hostility, and anger. However, perhaps these emotional responses are due not to withdrawal, but due to an increased awareness of unresolved emotions. If smoking dulls emotions, logically quitting smoking allows awareness of those emotions to bubble up to the surface. If emotional issues aren't resolved, a smoker may feel overwhelmed and eventually turn back to cigarettes to deal with the uncomfortable feelings.

Instead, when you smoke, the carbon monoxide in the smoke bonds to your red blood cells, taking up the spaces where oxygen needs to bond. This makes you less able to take in the deep, oxygen-filled breaths needed to bring you life, to activate new energy, to allow health and healing, or bring creative insight into your problems and issues. The bottom line here is that, once again, even though it is well known and documented that smoking is an entirely unhealthy activity, there are a myriad of reasons why people smoke. Self-defeating behavior is the culprit; intellectually, we know that smoking is bad. But somehow the will to stop just isn't there.

Financial Examples of Self-Defeating Behavior

Now that we have reviewed some non-financial examples of self-defeating behavior, we can now turn to behaviors that should be equated with poor investment performance but are repeated by investors month after month, year after year, cycle after cycle.

Number 1: The Return Chaser

One of the most basic of human investment instincts is to be “in the know” regarding the latest investment trend. How silly we feel when we are at a cocktail party or barbeque in our community and we join a conversation in progress about how your neighbor just made a killing on XYZ stock that participates in ABC hot industry. Why am I not participating in this money-making opportunity, you ask yourself? This occurred with Internet stocks in the late 1990s and then with real estate during the subsequent decade and now potentially with some social media companies.

At one time or another we have all seen someone who epitomizes this type of investor—or maybe this is our own behavior! These folks follow the latest trend, paying no attention to valuation and/or have no rational basis for making an investment and “jump in” without an exit strategy or plan to get out when a profit has been made—if one is ever made. The investment may go up but since no plan is in place, the investment ultimately turns sour and losses ensue.

As investors we must resist the urge to participate in such schemes and steer clear of these money-losing opportunities. Our own behavior is often the culprit and we need to overcome our natural instincts to participate in less-than-rational investment schemes—or at least have an exit strategy if the decision is made to participate. Later in the book we will look at individual behaviors that account for chasing returns as has been described here and devise strategies for overcoming these behaviors.

Number 2: The Overconfident Gambler

It is not uncommon to come across the type of investor who thinks they are smarter than the average market participant, who enjoys the thrill of trading in and out of the market (i.e., like the thrill associated with gambling) and is more often than not on the losing end of the trade (with the occasional win to keep them in the game). And, being on the losing end of the trade often causes even more of the gambling behaviors to kick in, so that they engage in the same risky trading behavior in an attempt to get back to even. This example is in contrast to the person who avoids such behavior (or keeps it to such a modest amount that it does not affect long-term wealth creation) and manages to save and invest over long periods of time to build wealth gradually. Notice a pattern here? This example is, of course, nearly identical to the yo-yo dieter in the non-financial examples presented in the last section. The dieter attempts to lose weight quickly on a regular basis only to gain it back. (In this case, it's the opposite—the person attempts to gain wealth quickly only to “lose it back.”) Figure 23.2 illustrates the overconfident gambler versus the opposite type of investor, who I will call the saver/investor. Both started at 25 and are currently 50 years old. Figure 23.3 extends out in time to show that there are still opportunities to change behavior even at mid-life.

Figure 23.2 Saver-investor versus the Over-Confident Trader

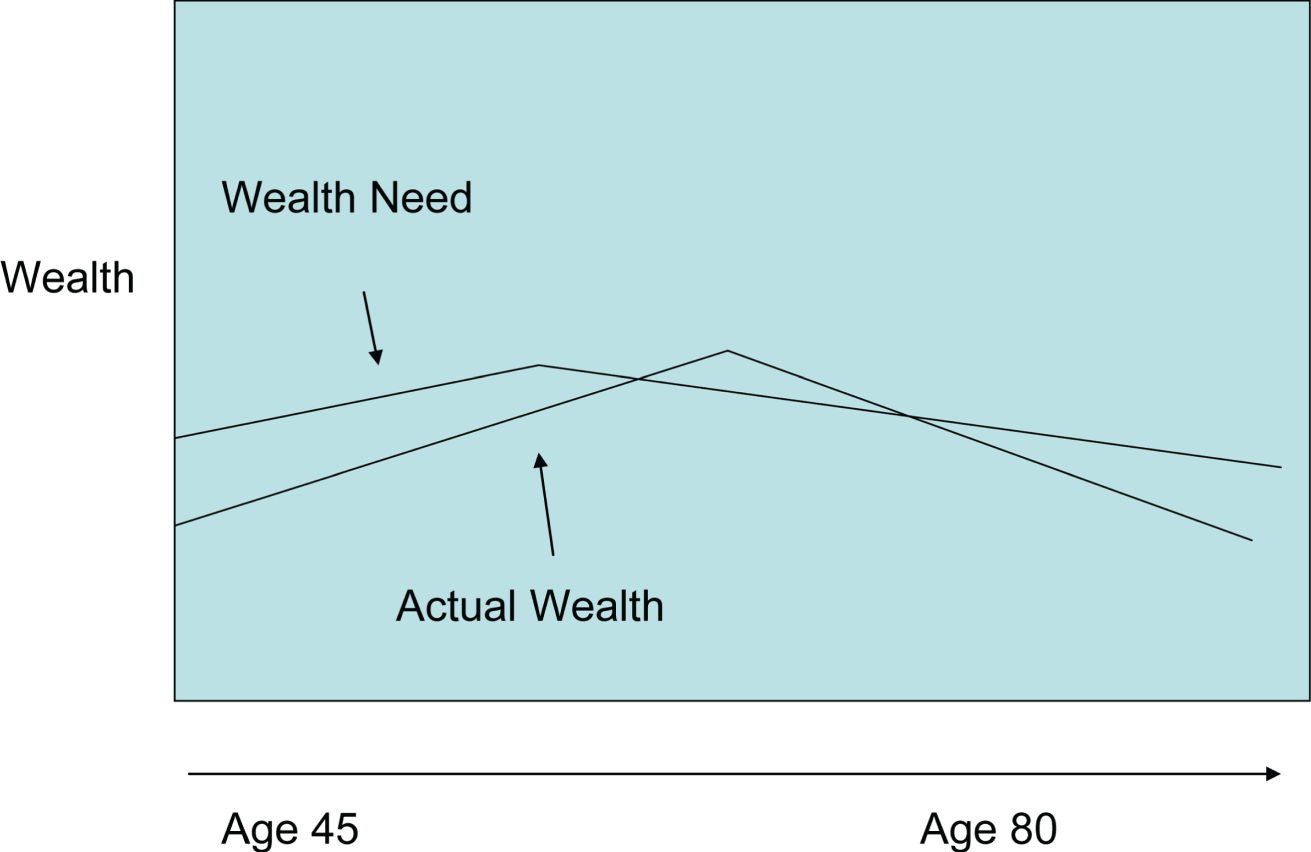

Figure 23.3 The Risk-Averse Investor

Naturally, this chart does not represent reality perfectly but you get the point: it's not hard to tell which kind of person you want to be. So, why can't we do it? The answer is we can, but we first need to identify the key factors that are rendering us incapable of engaging in good behavior.

Number 3: The “Too Conservative” Investor

Although not as common, there exists a class of investor that is too conservative in their thinking. They are afraid of losing money to a down stock market, whether through previous personal experience or not, that they simply won't accept any amount of risk. The failure with this approach is that people who cannot accept some amount of risk also risk outliving their money. The following diagram illustrates. Early into one's career, earning may not keep pace with the demand for funds, due to expenses like college and housing. At some point during mid-career, these expenses are hopefully surpassed by earnings and debt is reduced. The later in life, one's working career can end either voluntarily or not, and cash needs are surpassed by income. If one does not accumulate enough of a nest egg and invest it wisely, there can be a situation where one may outlive one's assets. This is demonstrated in Figure 23.3. Certain people in this situation intuitively know that they need to increase risk, but simply cannot take action to do it. They know concepts such as inflation and low yields on bonds but will not do what it takes to take the risk to build wealth.

Similarly, this chart does not represent reality perfectly but you get the point: You don't want to be in a situation where you don't have enough money as age increases. Taking risk in this case is advisable. In other cases, advisors spend a good deal of time talking people out of taking risk.

We have reviewed three very basic situations in which we have identified a type of investor. The intent was not to go into great detail but to provide situations in which it is difficult to control one's impulses toward a certain action or behavior. As we saw with the non-financial situations, people know they are taking actions that are not in their best interest. Similarly, in the financial examples, we saw that people can make financial decisions that are not in their best interest even when they know they should take a different path. In many other cases, people may not be aware of their irrational behavior and they need their advisors or other close relations to help them understand they are making mistakes.

Notes

- 1 Source: http://www.womenfitness.net/over-eating.htm

- 2 “Top 10 Triggers for Over-eating.” Women Fitness—A Complete Online Guide To Achieve Healthy Weight Loss and Optimum Fitness. Web. 05 July 2011. http://www.womenfitness.net/over-eating.htm.