4. The Biggest Ponzi Scheme in History: The Myth of Quantitative Easing

In 1920 the Boston Post contacted Clarence Barron, the founder of Barron’s, to investigate a man who claimed to be racking up remarkable gains for investors in an arbitrage involving the purchase of postal reply coupons in one country and their redemption in another. Charles Ponzi, the developer of the scheme, sought to convince investors that differentials in inflation rates between countries had created an opportunity for investors to purchase the postal reply coupons on the cheap in one country—particularly Italy, and redeem them in another—chiefly the United States, an arbitrage that Ponzi said would enable investors to grow their money by several fold if they invested with him. There in fact were differences between the price of postal reply coupons postage bought in countries outside of the United States and their redemption value, but there were substantial barriers preventing any actual arbitrage, including enormous logistical challenges having to redeem the coupons, which were of low denominational value. Ponzi birthed and perpetuated the scheme nonetheless.

Barron sought to expose Ponzi’s scheme, noting in articles that eventually brought the Post a Pulitzer Prize, that to support the claims that Ponzi’s investors had on the investments he had supposedly made for them that there would have to be 160 million postal reply coupons in circulation when in fact there were only 27,000. These and other questions led an angry and suspicious crowd to gather outside of Ponzi’s Securities Exchange Company, which was located in Boston on School Street, a very short street and the site of the first public school in the United States. Ponzi, who was famous for his deceptions, convinced many in the angry crowd to stay calm and leave their money with him, enticing them with little more than his charm, donuts, and coffee. It wasn’t the first time that investors would be misled by the potential for future profits and simple trappings. Donuts and coffee? Really? Is it this easy to get investors to part with their money? Yes, it seems.

From Donuts to Quantitative Easing (QEI and QEII): The New Profit Illusion

Charles Ponzi offered donuts to turn back a suspicious crowd of investors before his scheme was eventually found out. The Fed would need millions of donuts to sate the appetites of the literally millions of investors worldwide that hold U.S. Treasuries in what has become the greatest Ponzi scheme of all time: the creation of a scourge of debt so large that the Fed itself has had to purchase the debt to keep the scheme going. To do so, the Fed simply pressed the “on” button to its virtual printing press, crediting the account of the U.S. Treasury with the money it needed to perpetuate the Treasury’s endless borrowing. In the process, the Fed kept the demand for U.S. Treasuries deceptively high, drawing in many classes of buyers, including households, banks, pension funds, insurance companies, and, especially, foreign investors. Their combined purchases creates a profit illusion, with investors believing that they will continuously reap profits from perpetually falling bond yields and rising bond prices, just as they have had opportunity to do over the past 30 years, amid the great secular bull market for bonds.

It can’t last. At the Keynesian Endpoint, the Federal Reserve’s colossal bond purchases will likely, to the chagrin of millions of unsuspecting bond investors, bring about an end to the bull market in bonds. The Fed’s purchases have the sweet aroma of a freshly baked jelly donut, and many a bond investor has been drawn to its savory sugary taste. The whiff of rotten eggs is what investors should instead smell, but this is easily hidden with a nose pin, which the Fed places on the noses of each investor, with the goal of creating perpetual serendipitous moments that in the eyes of investors transform the rotten stench into something far more delectable. Ultimately, the stench of the Federal Reserve’s bond purchases will seep into the nostrils of investors all around the world when it becomes glaringly obvious that the Fed can’t possibly continue as the Treasury’s main source of demand for long. Moreover, Treasury investors will realize that the Fed’s purchases themselves create financial and economic conditions that are bad news for them primarily because the purchases confiscate their inflation-adjusted returns as well as the purchasing power of their dollars. Worse are the capital losses that investors in Treasury securities may incur from having bought into the Ponzi scheme at prices inflated by the Fed’s purchases, sort of like playing a game of hot potato and getting stuck with the potato when the Fed abruptly leaves the game.

The Intended Purpose of QEI and QEII

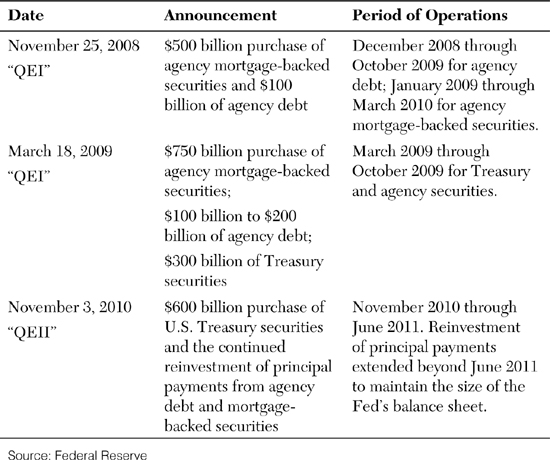

The ultimate intention of QEI and QEII differed from its initial intention, as shown in the language the Fed used to describe QEI, which was announced on November 25, 2008, and QEII, which was announced on November 3, 2010:

“QEI,” announced November 25, 2008: This action is being taken to reduce the cost and increase the availability of credit for the purchase of houses, which in turn should support housing markets and foster improved conditions in financial markets more generally.

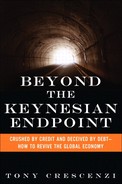

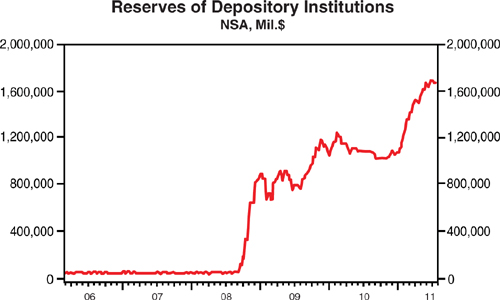

Just how effective was the Fed in supporting the housing market? Not much! This is evident in Figure 4-1, a chart that makes it blatantly obvious why there is such a striking difference between the way the Fed described the intentions of QEI and QEII.

Figure 4-1. Low mortgage rates failed to work their usual magic

Source: Census Bureau/Haver Analytics

“QEII,” announced November 3, 2010:

To promote a stronger pace of economic recovery and to help ensure that inflation, over time, is at levels consistent with its mandate, the Committee decided today to expand its holdings of securities.

The bottom line is that the Fed decided the best way to combat having hit the so-called “zero bound” on rates and ease financial conditions further was to endeavor to lower longer-term interest rates, which, in the Fed’s vernacular are those rates that are as short as one year and beyond, although it tends to mean two years and beyond.

Pocket Pickers

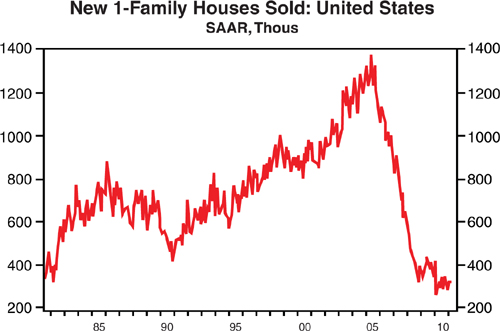

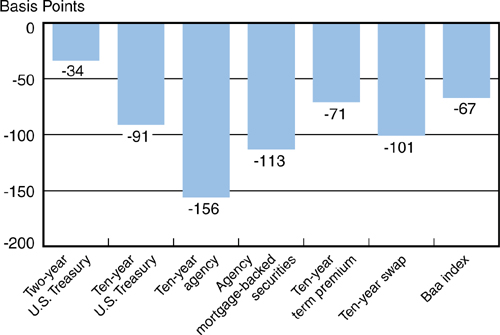

With the announcements of QEI and QEII and the purchases that would follow, the Federal Reserve in essence began to pick the pockets of Treasury bond investors throughout the world. To be sure, the purchases were as sweet smelling as a dozen jelly donuts when they began because they fattened the bellies of many investors who held them through the very substantial price gains that resulted from the sharp decline in Treasury yields (Figure 4-2).

Figure 4-2. Investors reaped big gains from big declines in Treasury yields

Source: Federal Reserve Board/Haver Analytics

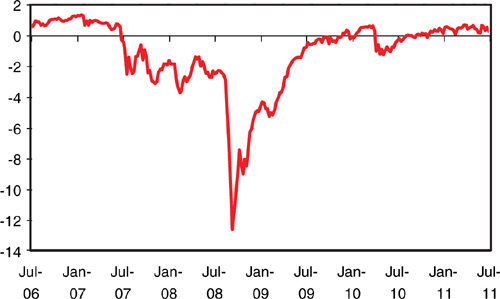

The problem, however, is that the Fed essentially robbed Peter to pay Paul, by pushing interest rates below the rate of inflation throughout much of the yield curve (as shown in Figure 4-3), by reducing the value of the U.S. dollar by pushing short-term interest rates below what investors could earn on investments in other currencies, and by increasing the supply of dollars in the world financial system.

Figure 4-3. Real yields on Treasury securities have plunged

Source: Federal Reserve. Bureau of Labor Statistics

Peter was the unsuspecting investor in Treasury securities drawn into the Ponzi scheme by the allure of ever-rising Treasury prices, as well as money market investors and fixed-income investors and savers who depend on interest income to either support or enhance their livelihood; Paul was everyone else invested in everything else.

How QEI and QEII Played Out

Table 4-1 shows the various announcements associated with QEI and QEII and the schedule of long-term securities purchases the Fed engaged in.

Table 4-1. Announcements by the Federal Reserve of Its Long-Term Securities Asset-Purchase Programs (LSAPs), aka QEI and QEII

Numerous studies and common sense tell us that the Fed’s large-scale asset purchase program (LSAP) drove interest rates lower across the fixed-income spectrum and in response lowered risk aversion substantially enough to drive investors into riskier assets and thereby loosen financial conditions. Figure 4-4 shows the cumulative changes in interest rates for various fixed-income instruments for eight “event days” associated with announcements of LSAPs studied by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.1 All told, the study by Gagnon, Raskin, Remache, and Sack suggest that the cumulative change for Treasury yields on days the Fed influenced expectations for the total future amount of LSAPs was a whopping 91 basis points, and the study doesn’t even include the effects of QEII when rates dropped very substantially in response to its voyage! An even larger footprint was left on agency securities and agency mortgage-backed securities.

Figure 4-4. Cumulative interest changes on baseline event set days

Sources: Bloomberg L.P.; Barclay’s Capital; Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

The decline in longer-term interest rates is the result of a decline in the so-called term premium for market interest rates, which is to say the extra yield that investors expect to receive over and above the average of expected future short-term interest rates for the many risks associated with holding a longer-term security, including the uncertain amounts of volatility, liquidity, and inflation that will occur over a longer-term horizon, in addition to numerous other uncertainties that can arise over time. The Fed’s impact on longer-term rates therefore resulted more from a decline in the term premium for long-term rates than from indications the Fed would likely keep short-term rates low for an extended period, which the Fed repeatedly said it would in the policy statements it delivered following its regularly-scheduled FOMC (Federal Open Market Committee) meetings beginning in March 2009. That month coincidentally marked the bottom of the stock market following the onset of the financial crisis.

The portfolio-balance effect on term premiums for longer-term securities resulted from the perceived reduction in risks associated with holding these securities as described by Tobin (1958, 1969).2, 3 The way it worked for the Fed is relatively simple: LSAPs removed a large amount Treasury, agency, and agency mortgage-backed securities from the secondary market, thereby reducing the amount of “duration,” or interest-rate risk, that the remaining holders of these securities had to bear for changes in market interest rates. In essence, the Fed reduced the amount of assets whose direction could be subjected to influences such as those from short-term oriented investors, leaving the remaining stock of assets to those more inclined to place a premium on the assets, including pension funds, central banks, and investment managers, for example, because these entities have an intrinsic need for duration owing to their varied needs for duration. A pension fund, for example, has longer-term liabilities it must attempt to match with assets, including fixed-income assets such as U.S. Treasuries. In this way, the Federal Reserve kept the game going, encouraging traditional buyers to continue buying by using its printing press to reduce the amount of longer-term securities in circulation.

The House of Pain: How Punishingly Low Rates Bolstered Stocks, Other Assets, and the Economy

The rebalancing effect resulting from the Federal Reserve’s large-scale asset purchase program stretched across the gamut of financial assets, resulting in a substantial loosening of financial conditions, as evidenced by the collective performance of corporate equities, corporate bonds, and other financial assets, which is summed up in the Bloomberg financial conditions index shown in Figure 4-5.

Figure 4-5. Bloomberg Financial Conditions Index. The Bloomberg Financial Conditions index combines yield spreads and indices from the money markets, equity markets, and bond markets into a normalized index. The values of this index are z-scores, which represent the number of standard deviations that current financial conditions lie above the average of the 1994–June 2008 period.

Source: Bloomberg

The movement into riskier assets that was encouraged by the Federal Reserve can be visualized by looking at a concentric circle, with the least risky assets at the center and the riskiest assets at the perimeter of the circle. Prodding investors to move out the risk spectrum to bolster the value of risk assets was a major part of the Fed’s strategy, and it was highly successful, with the riskiest assets outperforming other assets amid the Fed’s buying binge.

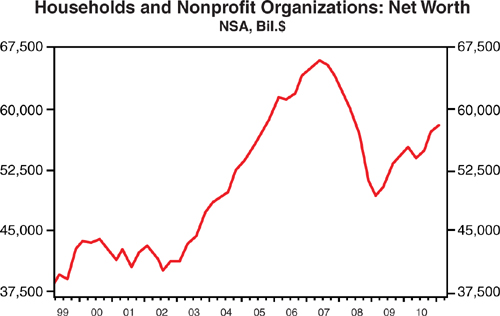

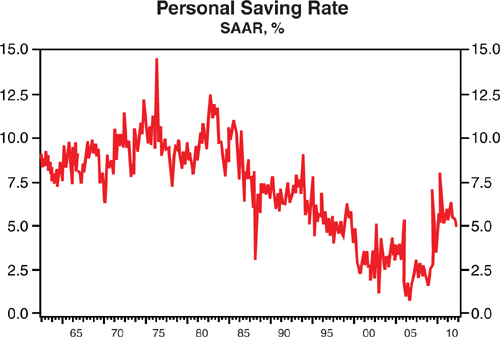

Gains in the value of financial assets helped restore a chunk of the $16 trillion in financial wealth that households lost during the financial crisis, thereby encouraging them to slow their effort to increase savings and instead do what they have cherished doing for decades: consume. These trends are shown in Figures 4-6 and 4-7.

Figure 4-6. Net worth of households and nonprofits

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis/Haver Analytics

Figure 4-7. Why save when your stock and home values are climbing? Prices never fall. Surprise! Yes they do.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis/Haver Analytics

Now, if you are thinking that the gains in wealth are funny money, you’re right because they resulted from the dual effect of the decline in term premiums for long-term assets and the migration of money out the risk spectrum, both spurred by the Fed’s printing press, which has nothing to do with ingenuity or innovation or gains in national wealth. Nor were the gains the result of any increase in the three so-called factors of production that facilitate output: land, labor, and capital goods. Land refers to not only the quantity of land available for output, but the many goods that can be derived from land, such as food, energy, and metals, among others. Labor includes both the quantity of people and their productive capabilities, their skill sets, attributes these days thought of as human capital. Capital goods refer to factories, machinery, tools, technology, and buildings used in the production of goods. Each of these factors of production has proven throughout history to be vital to building the wealth of nations, but they had nothing to do with the rebound in wealth in the United States following the wealth destruction that took place from the onset of the financial crisis. It was the Fed’s printing press that restored the wealth lost—wealth, mind you, that was previously built on debt. That last point is important because it suggests that the wealth that was destroyed should remain destroyed unless the decades of claims that originated as claims against future wealth are repaid and true wealth is built, either via increases in the factors of production or increases in the national savings rate, which can only occur if the U.S. eliminates it massive budget deficits and or increases its trade balance with the rest of the world by an amount larger than the size of its budget deficit.

The Biggest House of Pain of Them All: The Money Market

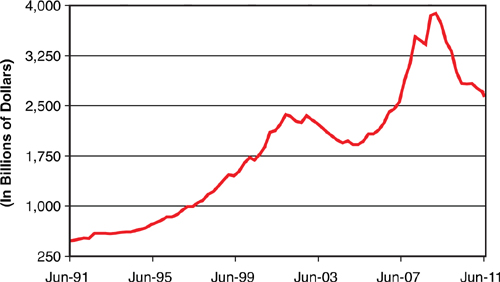

Much of the migration into riskier assets was encouraged by the Fed having created a “house of pain,” through not only a decrease in term premia for longer-term bonds, but also its zero interest rate policy, commonly known as ZIRP. The Fed mercilessly created an investment climate in the money market so punishing that it drove investors to seek refuge in other assets. This is evident in the exodus from money market funds that in 2009 resulted in outflows of $280 billion and a whopping $392 billion in 2010. Substantial outflows continued into 2011 (Figure 4-8). These outflows helped other asset classes to flourish, just as the Fed hoped.

Figure 4-8. Total amount invested in money market funds

Source: Investment Company Institute (ICI)

In addition to ZIRP, further downward pressure on money market rates occurred in April 2011 when the Federal Deposit Insurance Company (FDIC) began assessing fees on not just deposits, but also other liabilities, including repurchase agreements, or repo, the market by which banks exchange their securities holdings (usually Treasuries) for cash, at a rate close to the federal funds rate, the rate targeted by the Fed at between zero and 0.25 percent since December 16, 2008. The action significantly reduced the attractiveness of the $2.5 trillion repo market (the biggest segment of the money market) as a source of bank funding because it closed the arbitrage opportunity that banks since 2008 had taken advantage of by borrowing in the repo market at rates of around 15–20 basis points and then depositing the money at the Fed to earn the 25 basis points the Fed paid on excess bank reserve, thus netting the difference. For investors in repo, which include many of the nation’s top investment firms as well as money market mutual funds, the FDIC’s action was like salt in their wounds because they were already taking a pounding from the relentless increase in financial liquidity resulting from QEII, which was pressuring repo lower, like a steel roll sitting atop a pancake.

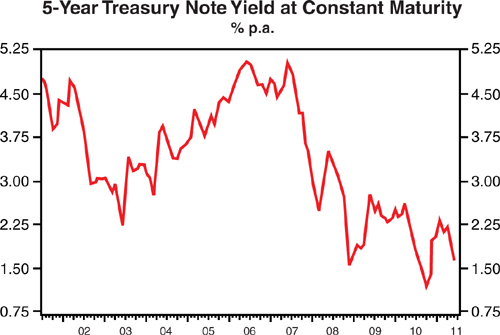

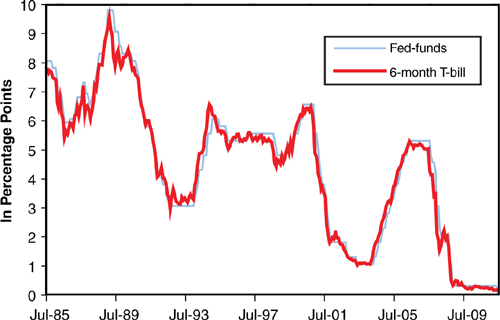

Needless to say, other money market rates such as those for T-bills, commercial paper, and certificates of deposit were also sitting beneath the steel roll, as they always do when the Fed is rolling it, because these rates are very closely tied to the federal funds rate, as shown in Figure 4-9. In other words, the Federal Reserve can at any time pick investors’ pockets through what to money market investors is a dastardly form of financial repression that forces them to receive rates of interest that are below the inflation rate—a negative real rate of return.

Figure 4-9. Money market rates closely follow the fed funds rate, which is controlled by the Federal Reserve.

Source: Federal Reserve

What the Fed and Yucca Mountain Have in Common and Why “Quantitative Easing” Is a Misnomer

History is laden with failed attempts at creating new money to shed debt. Greek tyrant Dionysius of Syracuse, now Sicily, at around 400 B.C. resorted to coinage debasement when his fortunes declined. Germany, of course, debased its currency before World War II, leading to hyperinflation. More recently, Zimbabwe printed massive amounts of currency, also leading to hyperinflation—I purchased trillions of Zimbabwe dollars on eBay for a few U.S. dollars! Such are the ravages of excessive use of the printing press.

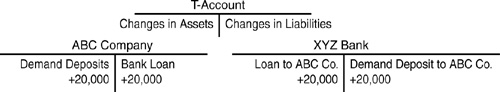

Debasement of indebted nations’ currencies depends importantly on the excessive creation of money. Today, the deleveraging process is preventing this from happening. This brings us to a critical point: By themselves, increases in the quantity of bank reserves resulting from central bank activities cannot boost the money supply; only banks can create money supply. To illustrate the point, let’s look at a sample T-account (that is, a basic two-column accounting table; see Figure 4-10) for a U.S. bank and its customer.

Figure 4-10. The rule of money creation: only banks can expand the money supply

ABC Company borrows $20,000 from XYZ Bank, which, like all banks, is an intermediary between the Fed and the public. Banks, in fact, are the only entities allowed to offer checking accounts.

As the T-account shows, the immediate effect of the loan is to increase total demand deposits by $20,000, but no decrease has occurred in the amount of currency in circulation. Therefore, by making the loan, XYZ Bank has created $20,000 of new money supply.

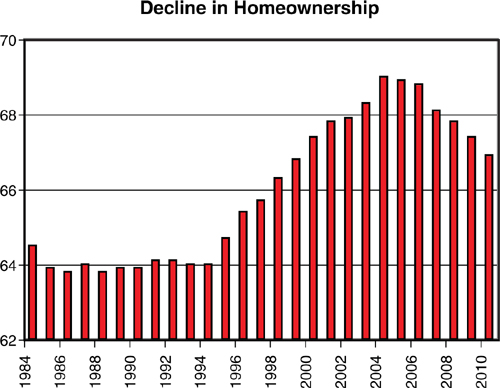

The ability of banks to create loans and thus boost the money supply is what worries those who focus on the quantity of reserves that the Federal Reserve has injected into the financial system. Roughly $1.5 trillion of excess reserves were injected into the U.S. banking system as a result of the Fed’s asset-purchase programs, which is about $1.5 trillion more than normal—banks typically would rather lend their excess reserves than leave them deposited at the Fed (Figure 4-11) where they earn next to nothing.

Figure 4-11. Banks are depositing their reserves rather than lending them.

Federal Reserve Board/Haver Analytics

In normal times, the banking system can turn one dollar of reserves into about eight dollars of new money supply because a bank can lend 90 cents on the dollar after putting 10 cents aside at the Fed for a reserve requirement. A bank on the receiving end of the 90 cents can lend out 90 percent of that, or 81 cents, and so on and so forth until presto: One dollar becomes eight dollars. This is why the monetary base, which represents the money, or reserves, injected into the financial system by the Federal Reserve, is called “high-powered money.”

Bank reserves in their enormous quantities therefore are toxic, but in the same way that nuclear waste is of no danger as long as it is tucked away either in Yucca Mountain or concrete casks, bank reserves are of no danger to fueling inflation as long as they are held at the Fed. This is why the term “quantitative easing” is actually a misnomer—no actual increase in the money supply resulted from the Fed’s creation of bank reserves because banks did not lend out the reserves. Only when the concrete cracks—when banks utilize their excess reserves and lend again—can the creation of reserves be called quantitative easing. When this happens and the money thus begins to seep out of Yucca Mountain, the Fed will begin to remove the toxins, eliminating the dangerous potential for excessive coinage, or so we hope.

Draining the Toxins

How will the Fed drain the toxins? Here is the expected sequencing:

1. Allow the run-off of agency mortgage-backed securities: Many of the mortgage payments made by American households go toward paying off mortgages held by the Federal Reserve in the form of mortgage-backed securities. As households pay their mortgages, rather than recycle those payments with the purchase of Treasury securities, the Fed will simply hold the money, essentially removing the money from circulation. This will amount to between $15 billion to $20 billion per month.

2. Conduct reverse repos: The Fed will conduct open market operations whereby it will lend securities to the nation’s primary dealers in exchange for cash. Primary dealers are required to participate in these operations, which will drain around $600 billion or so from the financial system.

3. Auction term-deposits through the Fed’s Term Deposit Facility (TDF): The Fed will offer term-deposits via an auction process whereby banks bid to earn a desired yield for deposits they keep at the Fed. The rate is generally up to a few basis points at most above the interest rate the Fed pays on excess reserves and hence attractive to banks. The TDF will drain approximately $200 billion from the financial system.

4. Raise interest rates: In an interest-rate targeting regime, the only way to alter the interest rate is to adjust the supply of money. The Fed will therefore have to drain reserves from the banking system in order to increase the cost of money.

5. Sell securities: Selling securities is last in the sequencing for a number of reasons. First, the Fed has no experience selling securities of the magnitude it must sell them this time around if it is to shrink its balance sheet. This means the Fed can’t be sure of the impact that its actions would have on both the financial markets and the economy. Second, the market’s capacity to hold mortgage-backed securities is almost certainly lower than it was before the Fed bought $1.25 trillion of them. Third, any sale of mortgage securities could weaken an already weakened housing market by boosting the cost of mortgage finance. Fourth, the Fed likely has no appetite for selling any of its assets at a loss out of fear of political backlash.

Let’s hope that when the money starts to seep out of Yucca Mountain that the Fed’s Geiger counters are both working properly and in use at the Fed. If not, we will have a serious inflation problem at some point. The most likely scenario is that the Geiger counters will work, be heard loud and clear at the Fed, and prompt a swift and effective response. Again, let’s hope.

Why $1.25 Trillion of Mortgage Buying Did Diddly for Housing

So far we’ve talked a great deal about how QEI and QEII affected economic and financial conditions. Let’s now talk a bit about how little it did for housing. Recall that when the Fed announced QEI in November 2008, it said it was taking the plunge to “reduce the cost and increase the availability of credit for the purchase of houses, which in turn should support housing markets and foster improved conditions in financial markets more generally.” Oh, yes, I forgot: QEI was for the housing market. Did it help? Not an iota. Let’s take a closer look at what happened. It offers lessons about the challenges indebted nations face at the Keynesian Endpoint, which require a reduction in debt and in the excesses built up in the real economy by indebtedness.

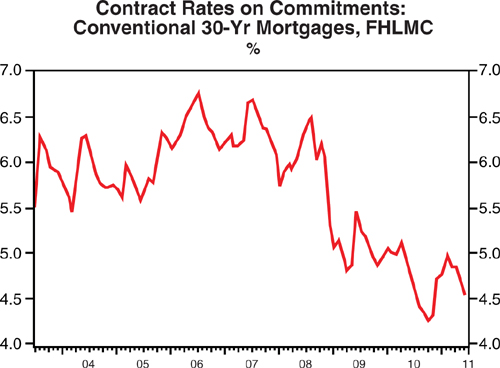

There are a number of reasons why the housing market did not respond to the decline in mortgage rates shown in Figure 4-12. One of these is the very sharp tightening of lending standards that occurred in response to the onset of the financial crisis. According to the Federal Reserve, the percentage of banks that tightened were tightening their lending standards increased to about 75 percent in the second quarter of 2008. The subprime market was essentially shut down, with almost no new subprime mortgages originated in the United States in the aftermath of the crisis. This contributed to a decline in the homeownership rate, which is shown in Figure 4-13.

Figure 4-12. Mortgage rates fell after the crisis. Housing languished nonetheless.

Source: Federal Reserve Board/Haver Analytics

Figure 4-13. Homeownership rate in the United States

Source: U.S. Census Bureau

No amount of Fed liquidity could make banks lend to subprime borrowers after they took such heavy losses from subprime mortgages. This is one of the lessons of the post-crisis policy response, the idea that liquidity cannot solve a solvency problem. It merely forms a bridge, and often it is a bridge to nowhere.

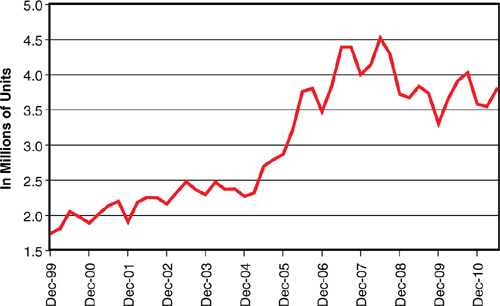

Liquidity and the cost of money are also of no use when there is excesses in the real economy that need to be worked off. The excesses arise from debt-led consumption patterns that can’t possibly be sustained without sufficient growth in real incomes and savings, including at the national level. These were lacking before the financial crisis began, and they remained barriers to the housing market’s recovery in its aftermath. Figure 4-14 makes clear that the massive amount of excess supply of homes presented a formidable challenge to policymakers hoping to revive the moribund housing market.

Figure 4-14. Number of existing homes for sale

Source: National Association of Realtors

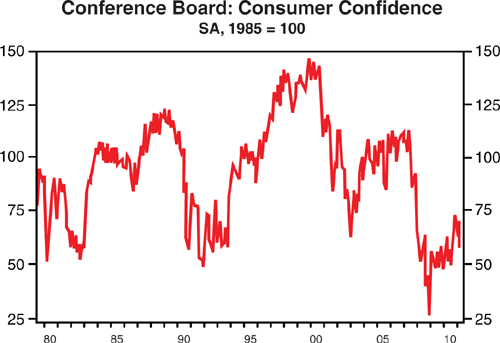

Confidence was also lacking in the housing market, and it, along with income growth, is one of the two market pillars. Figure 4-15 shows the miserable level of consumer confidence that resulted from the financial crisis. No amount of liquidity can make people feel better about buying houses when they are fearful about the future both for housing and the labor market.

Figure 4-15. Housing can’t bounce if consumers feel glum.

Source: The Conference Board/Haver Analytics

What Then Will Revive Housing Beyond the Keynesian Endpoint?

If the Fed and Washington can’t revive the housing market, how will it recover? The answer is to look beyond foreclosures and finance to demographics and construction. In doing so keep in mind this idea: People are born short a roof over the heads, and they eventually have to recover. So as long as the population grows and the construction of new dwellings stays below the household formation rate, empty space will fill up, and prices will eventually stabilize.

A population that grows 2.7 million persons per year at a time when construction is at a standstill will be sufficient over a few years to bring the single-family vacancy rate low enough to boost rents and—much later, home prices. This is not really a prediction—it is already happening. Any downturn in prices shouldn’t go far because the demographic influence will be too powerful, especially now that the U.S. economy has stabilized because household formation will increase—roommates will get tired of each other, and mama’s boys will finally move out of the house (although not in Italy, where mama’s boys stay at home far longer than seems normal!). Population growth of 2.7 million per year should result in about 1 million new households, a rate that far exceeds the pace of new construction, which is running under 500K per annum. (Some housing starts are actually replacement homes, which means the actual increase in the housing stock is running below the 500K annual rate for housing starts.) This will inexorably lead to a decline in the vacancy rate. So yes, the homeownership rate will decline, but so will the vacancy rate, which will boost rents and hence the value of those empty homes.

Housing will muddle through its inventory dilemma for as long as the economic recovery continues. Economic growth is important during this time to prevent any meaningful decline in home prices. Already about 25 percent of homeowners owe more on their mortgages than their homes are worth. A drop of another 10 percentage points could put another third of homeowners below water. The second-round effects of such a decline would be extremely damaging to the economy and spark another round of deleveraging economy-wide.

Who Will Buy Treasuries if the Fed Doesn’t?

QEI and QEII resulted in the purchase of about $2.5 trillion of Treasury, agency, and mortgage-backed securities, and in the first half of 2011 the Federal Reserve purchased nearly as many Treasuries as were issued by the Treasury Department. In other words, the U.S. government was heavily reliant upon the Fed to finance the U.S. government. This isn’t to say the Treasury would have been unable to fund itself if not for the Fed, but what it does mean is the Treasury would have been unable to fund itself at the interest rate levels it did.

It is therefore important to ask what will happen when the Fed stops buying, particularly given the vast amount of Treasury securities the U.S. must issue in order to fund itself. It certainly is a pickle.

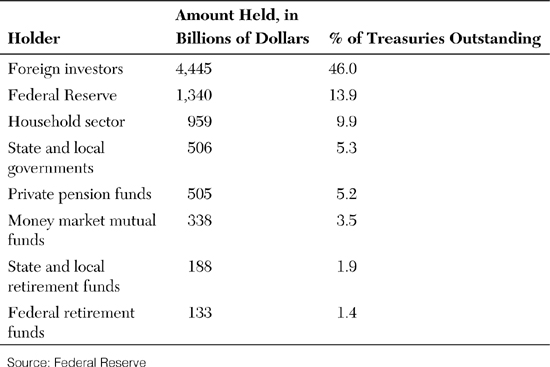

To answer the question, first consider who it is that owns Treasuries. Table 4-2 indicates quite clearly that the U.S. heavily relies upon foreign investors to fund itself, with foreign investors holding more than half of all U.S. Treasury securities outstanding. This cohort is therefore the most important and the one that Washington should be trying to please most. Yet, it’s not doing too well in this department because it has not done anything serious to tackle the U.S. debt problem. The inability of Washington to get its financial house in order puts the United States at serious risk of losing the confidence of foreign investors. If this happens, then the cost of borrowing will skyrocket in the United States, and the United States will be forced into austerity measures that will lower the standard of living for all Americans.

Table 4-2. The Major Holders of the $9.62 Trillion of U.S. Treasuries Outstanding as of March 31, 2011

Threats to the U.S. Dollar’s Reserve Status

Probably the biggest savior for the U.S. in terms of its ability to finance itself is the fact that despite all of the problems the U.S. faces, the U.S. dollar remains the world’s reserve currency, which means that more of the world’s transactions are conducted in dollars than any other currency. This provides an enormous amount of support to the U.S. dollar because it creates a large set of natural buyers, in particular, foreign central banks. Moreover, the United States is a superpower, and hence it is the world’s greatest power militarily, politically, and economically. The combination of these influences gives foreign investors confidence when investing in the United States.

Still, as ever present as these conditions have always seemed, the lines between the United States and other nations is blurring largely because of the ascension of other nations—China in particular. The root of this transformation is economic, but it is also political, with the rest of the world seen as having lost some of its confidence in the United States’ ability to lead following troubles in the Middle East.

On the economic front, the idea that investments in the United States are completely safe has lost some of its luster and is under threat. While the rest of the world is in the midst of a secular upswing, the United States is arguably in the midst of a secular downturn, brought on by an unwinding of the excess use of financial leverage, a lack of national savings, and large fiscal deficits.

In the past, investors did not question actions taken by the fiscal authority to assist the private sector. Times have changed. Today, investors have made sovereign credit risk their risk factor du jour. No longer are investors sitting ready with blank checks to underwrite fiscal profligacy. Like a banker, investors are asking themselves, “Would I rather lend money to nations such as the United States whose debt burden is worsening, or to nations where it is improving and in many cases already very low?” To many investors, including those in the United States, the answer is patently obvious.

For the United States, its hegemony in vital areas looks likely to be retained for quite some time, so any erosion of the U.S. dollar’s reserve status is likely to take many years, perhaps a generation or more. Where, for example, if not in U.S. dollars can the world house its roughly $10 trillion of international reserves? In the euro? Not likely given that Europe is also working through a sovereign debt dilemma. Investors can’t turn to China, either, despite its strong fiscal situation because China’s currency is not yet a free-market currency, and China has no bond market to house the world’s reserves.

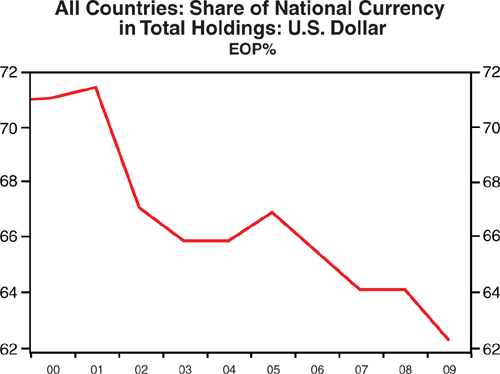

Central Banks Are Diversifying Away from U.S. Dollars

Although the U.S. dollar looks likely to retain its reserve status for quite some time, it has been losing its status slowly but surely for nearly a decade now, with more of the world’s reserves flowing to other currencies and into the real economy. For example, as shown in Figure 4-16, the U.S. dollar in early 2011 represented 61 percent of the world’s reserve assets, down from 71 percent ten years earlier. The euro during this time ascended from 20 percent of the world’s reserves assets to 26 percent. No speeding up of this trend is likely given Europe’s problems, but what is important to infer from these data is that they indicate the world has grown less confident in the United States, particularly now that it has reached the Keynesian Endpoint, because the United States can’t solve its problems by endlessly borrowing from the rest of the world.

Figure 4-16. The U.S. dollar is slowly losing its standing abroad.

Source: International Monetary Fund/Haver Analytics

Excessive U.S. Debts Will Drive Cash Flow Decisions Globally

The gradual loss of the U.S. dollar’s reserve status is driven by a conscious decision by the world’s central banks to diversify their reserve assets to not only minimize the risks associated with holding the currency of a heavily indebted nation—the United States—but to more closely align their reserves with trends in international trade, where the U.S. shares the stage with formidable players and is slowly seeing its influence erode. For example, China and Brazil in 2009 agreed to settle their trade invoices in their respective currencies bypassing the U.S. dollar as a means of settling trade between the two countries.

Facing losses from both a decline in the value of the U.S. dollar and low investment returns in dollar-denominated assets such as U.S. Treasuries, the world is actively seeking alternative investments. For example, China is investing in mining companies and commodities, and it is carving out shipping lanes, seeing these as better places to put their money. China knows that it will need commodities to produce goods it will sell to the world, so it seems it is making a surefire bet on its own future. It certainly seems a better bet than U.S. Treasuries.

Other nations are sure to follow China’s lead, recognizing that at the Keynesian Endpoint investments in indebted nations such as the United States, Japan, and those in Europe are unlikely to return as much as they used to. In this way, sovereign debt is likely to be a powerful influence that will the movement of global cash flows for many years to come.

It’s Time to Make the Donuts

QEI and QEII were necessary evils at a time when the U.S. financial system was on the brink, but they are unsustainable means of funding the U.S. government. Ultimately, the United States must own up to its past sins and let the deleveraging process play itself out. It can’t pretend that previous levels of demand can be restored simply by turning on the printing press at the Federal Reserve. The United States instead must recognize that only by increasing investment in its people, its land, and its infrastructure can it promote economic growth rates fast enough to justify consumption levels previously supported by a wing and a prayer—by debt.

For the Federal Reserve and the U.S. Treasury, it is time to make the donuts because there is a crowd standing outside, and although there is no wrongdoing to make them as angry as the crowd that stood outside of Charles Ponzi’s office before he was busted, they are just as anxious, and it is going to take a lot of convincing to get them to show up at the next Treasury auction and the one after that, and the one after that, and....