Ilike you; here’s my money!”

It’s not quite that easy, but those six words describe a condition and a result that often go together in sales. This principle is called the liking-agreement heuristic or balance theory (Stec and Bernstein, 1999), and it’s as dependable as cold weather and pure, drinkable water at the Canadian Rockies’ Athabasca Glacier.

Research shows that if a prospect likes you, your chances of inking the deal are far better than they would be if he or she felt neutral or outright disliked you. Although this makes perfect sense, when we understand exactly why it is so, we can use the principle to our advantage.

When a prospect has limited information about a product, cues become a primary source from which to formulate impressions, especially for relatively inexpensive items that do not require deep thought. In a study conducted by Wood and Kallgren (1988), those who knew the least were more compelled to process through the “disagree if the communicator is unlikable” heuristic.

Of course, it takes more than simply telling someone to like you or greeting a prospect with a big toothy smile, a firm handshake, and some cheery words to get her to like you. Developing rapport is a learned skill that comes easy to some and is terribly difficult for others; some people are naturally likable. Others are naturally, er, unlikable.

Did you ever meet someone and find that you were instantly comfortable with that person? In contrast, some people—for some weird reason—make you cringe with discomfort? Why?

Some people you can talk to as if you’ve known them your entire life. With others, being in their presence for five minutes feels like an eternity. There are dozens of factors at play, and many of them are occurring at an unconscious level. Unless they’re pointed out, they go completely unnoticed. They consist of subtle behaviors, movements, speaking patterns, and preferences that together project ease, discomfort, or powerful self-confidence. Some body movements inspire trust, whereas other actions cause you to withdraw or even make your skin crawl.

It’s challenging! With so many different kinds of people exhibiting different kinds of behavior and using different speaking and communication styles, all driven by a continually changing river of different thoughts and perceptions while they try to express themselves, how the heck can you build rapport or at least get on a level communication playing ground, let alone get them to like you?

I began studying Neuro-Linguistic Programming (NLP) in the late 1980s and was trained directly by Richard Bandler, Robert Dilts, Judith DeLozier, Todd Epstein, and John LaValle. I was personally certified by Bandler for his Design Human Engineering (DHE) and Train the Trainer programs.

NLP is an interesting topic, and although the three therapists whose work it was derived from—Milton H. Erikson, Virginia Satir, and Fritz Perls—were widely recognized as effective with patients struggling with all kinds of personal, psychological, and relationship issues, it also has considerable application outside of these important therapeutic areas. And while I haven’t personally verified all of its many claims, I can confidently say that when it comes to NLP’s findings and guidance regarding interpersonal communications, it’s right on the money.

My beliefs about NLP are as with many other things in life: there are elements of it that if properly employed can be useful and beneficial. For example, NLP’s prescriptions for rapport building are sound because they’re based on the commonly accepted idea that people for the most part tend to like people who are like themselves. Makes sense, right?

Enter the American anthropologist Ray Birdwhistell. In a 1970 study, he discovered that words account for only about 7 percent of human communication, tone of voice accounts for 38 percent, and body positioning and posturing deliver a whopping 55 percent of the meaning we convey during in-person (as opposed to telephone, text-ing, e-mail, etc.) conversations.

Do the math and you’ll see that 93 percent of what we communicate to others—and receive from them—happens unconsciously. This means that when you’re talking, you’re conveying a lot more than the words that are shooting out of your mouth. For example, your words might be saying, “Oh, I’m so sorry your mother is sick,” yet the 93 percent of the meaning of what you’re communicating through your tone and body language might be saying, “It’s about time that conceited hag kicked the bucket.”

As another example, consider poor Joe. Not being aware of the critical 93 percent of his communication, he asked his supervisor for a raise, saying, “Hey, boss, I really think I deserve an increase because not only do I love this job, I put my heart into it every single day. I work late and on weekends. I complete all my reports on time and always do my best to cut costs and boost productivity. I even defend you and your policies when others shoot them down.”

Although they’re short on specifics, facts, and figures (asking for a raise is a sales job first and foremost, and you should never forget that), Joe’s words pose no problem. However, his unspoken communication unconsciously appended the following to the end of his pitch: “Uh, I don’t believe a word I’m saying here and I’m, er, kinda nervous right now, but I thought I’d give it a shot anyway … uh, whatever.”

Do you see what this 93 percent of your communication could mean to your sales efforts? You may think you’re conveying a perfectly acceptable presentation packed with benefits, loaded with features and facts, and injected with just the right amount of emotion. You pull out the fancy sell sheets. You whip out the flipchart. Your fingers are performing Cirque du Soleil maneuvers across your iPad. But unfortunately, your untrained 93 percent is having the same effect as pouring two-part epoxy into your prospect’s wallet.

The result? Those credit cards aren’t coming out. But why? Because you’re focusing solely on your 7 percent: your words. Even though those words may be great, your body is saying, “Don’t trust me. Do you believe what I’m saying? I sure don’t.”

Is this really possible? Could the way you’re moving your body be throttling your potential to close more deals? Could it be that while you’re busy blaming your product, your sales manager, the economy, the weather, your leads, your lousy breakfast, and perhaps a few dozen other things, your number one problem is the way your body parts move?

Huh? The answer, of course, is yes. Salespeople never give it a second thought. They don’t even know about their unspoken 93 percent. But now you do. (Aren’t you glad you’re reading this book?)

Listen: this isn’t an NLP book, but I can give you a crash course in NLP rapport-building techniques that you can start using during your next sales presentation. The more rapport you have with your prospects and customers, the more you’ll sell. It’s as simple as that.

As with most things, the more you practice, the better you’ll get. At first you may feel conspicuous. You may think that your prospects know you’re using a technique to help you gain the upper hand. If you’re entirely artless and obvious about it, they may. However, when used subtly, these prescriptions typically evade detection. It’s similar to learning to speak a new language and then practicing by talking to native speakers. You often feel that the native speakers think that you’re “doing” something rather than simply talking. But all they hear are the words, not everything that’s going on in your mind.

Building Rapport with the Techniques of NLP

The whole idea is called pacing, and it’s defined by NLPers as a method used by communicators to quickly establish rapport by matching certain aspects of their behavior with those of the people with whom they’re communicating. Pacing consists of matching and mirroring and, once rapport is established, transitioning into leading so that the prospect follows.

Researchers at the Boston University School of Medicine studied videos of groups of people conversing. They observed a natural and unconscious coordination of movements, including head nodding, eye blinking rates, and arm and finger motions. Further monitoring revealed that the individuals who matched one another’s movements developed far deeper and obvious levels of rapport that were empirically demonstrated on EEG monitors by brainwave patterns that spiked at the exact same times. Amazing, no?

Okay, let’s discuss matching and mirroring. NLP teaches that to cause your “subject”—or prospect in our case—to like you, you change aspects of your physiology so that the subject unconsciously perceives you to be like him or her. In effect, the subject’s brain thinks, “Hmmm, this person does just what I do. I perceive more similarities than differences. He or she is similar to me.”

When I refer to matching, I’m talking about literally copying your prospect’s body language, posture, breathing, facial expression, voice tone and tempo, and representational predicates, which I’ll explain next. Mirroring consists of reflecting your prospect as if he or she were your mirror image. If she raises her left arm, you raise your right, as in a mirror image. Although it is more difficult to keep outside of conscious perception, mirroring can result in deeper levels of rapport. Matching, by contrast, is less rigorous. For example, the subject might scratch her right arm, and in response you might scratch your left arm. You have copied her movement, but not symmetrically.

Let’s look at an example of how this plays out. Imagine you’re pitching Fred on your new line of designer chocolates that you want him to start stocking in his candy store. You’re both sitting comfortably in Fred’s office, and you show him an exquisite assortment of candy boxes that look more like fine jewelry boxes. We’re talking gorgeous gold foil, silver ribbons, Victorian-era graphics of stately looking statues and architectural elements, a precisely cut sheet of parchment paper separating the lids from the candy, and a small antique-white, deckle-edged note card explaining the painstakingly laborious handcrafting required to produce these world-class chocolates. Heck, no wonder the stuff sells for an insane $90 a pound!

Fred doesn’t know you, but he agreed to meet because you promised him a chocolate windfall. The candy he now sells, by comparison, is garbage, and since his shop is in a neighborhood of wealthy people with not only lots of money to spend but also very good taste, the idea of carrying high-end gourmet chocolates makes good sense. For these reasons, he invited you in and wants to learn more.

Fred leans forward to look at the first box that you flourishingly place on the table in front of him. You match him by leaning forward and push the box closer to him. “Well, it’s clearly an upscale presentation; look at this fancy box. Yeah, I can see how my customers might be attracted to this,” Fred says as he runs his fingers across the gold foil lid, nodding, his businessman brain beginning to conjure up images of chocolate-driven cash filling his pockets. You match his movements and nod as well. He strokes his beard, squints his eyes, and turns the box over like a chicken on a rotisserie. You match him by picking up another box, rubbing your chin, squinting your eyes while looking at the graphics, and rotating the box, and then you respond, “You’re right. In fact, take a look, Fred, at how it clearly stands out among the average boxed chocolates. Your customers will immediately see the quality even before seeing the chocolates inside. This upscale packaging is like the headline for a good ad. It gets them to take the next step, to envision how great the product inside will be; it’s pure psychology”

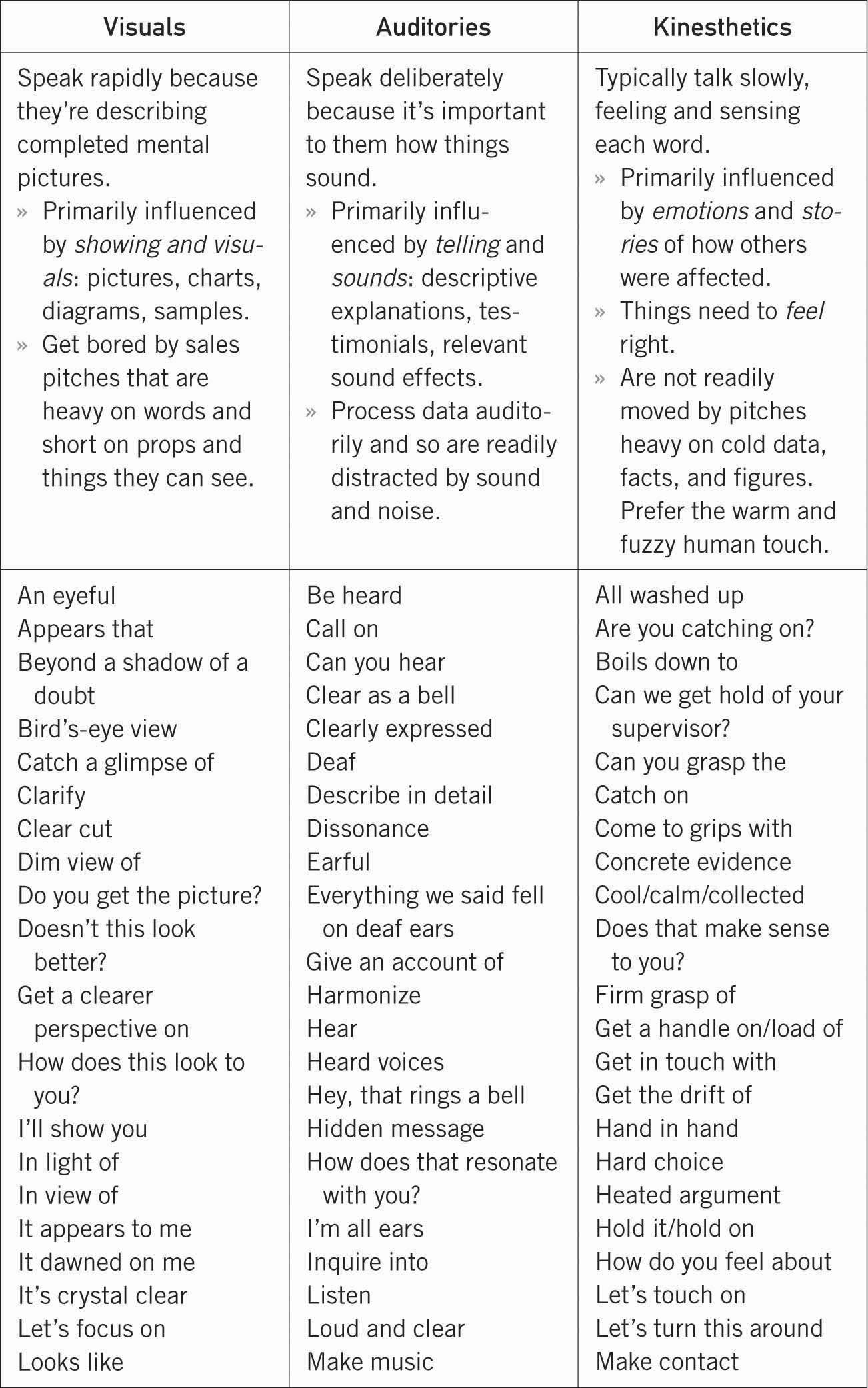

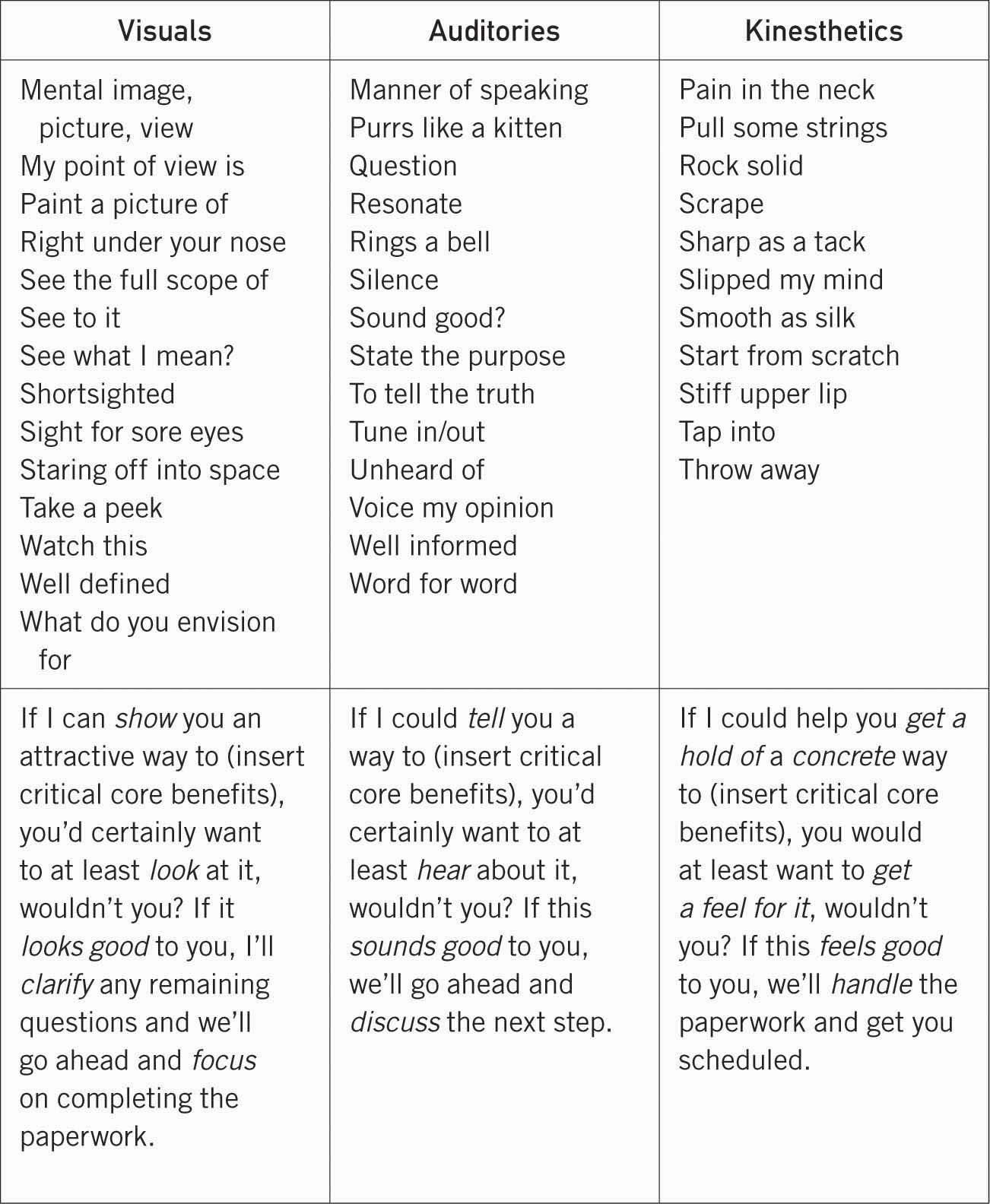

Notice how you’re matching Fred’s representational system predicates. You’ve discovered that Fred habitually chooses words that relate to vision. He tends to say things such as “I see that,” “It’s clear to me,” and other words and phrases that represent a visual mode of interpreting his world.

To clarify, in NLP, the term representational system refers to the senses that we use to experience everything around us. The words we choose to describe our experiences through these representational systems are called predicates.

Let’s not get bogged down in terminology. Remember our discussion about VAKOG in BrainScript 2: “The Psychology of Sensory-Specific Language”? You’ll recall that there are five different systems that make up our experience: V = visual, what we see; A = auditory, what we hear; K = kinesthetic, what we feel; O = olfactory, what we smell; and G = gustatory, what we taste.

Listen to people talking and you’ll discover that each person has an unconscious preference for one representational system (repsys), with visual, auditory, and kinesthetic being the most common ones. Knowing this gives us clues that can help us develop rapport. Simply listen to your prospects and customers and determine which mode they tend to favor and then match it.

Don’t get upset if their favored repsys isn’t apparent in the first minute or two of conversation. Your prospect isn’t going to blurt out a huge string of predicates to help you match him more effectively. You’re unlikely to hear, “Sure, I hear what you’re saying, and the profit potential is music to my ears, but what doesn’t ring true is your suggested pricing; that kinda shatters my impression that your company truly listens to and works in harmony with your retailers.”

I wish it were that easy. That’s why you match all the things that are immediately apparent: posture, body movements, speaking volume, pace and tonality, facial expressions, posture, and eye blink rate. NLP also suggests that matching breathing can be effective. The point is, you’re trying to make yourself as much like your prospect as possible to create an “I’m a lot like you” impression on her unconscious mind. If she speaks loudly, you do the same. If she’s shaking the foot on her crossed leg, you do the same. If she’s sitting on a 45-degree angle—ala William F. Buckley—you do it too.

If she’s talking slowly and deliberately and using generous hand gestures to punctuate her words, you match it. Of course, you want to do these things in as natural a manner as possible. You don’t want to give the impression that you’re playing monkey see, monkey do. That means that when she scratches her head, you don’t immediately scratch yours but wait a few beats before doing something similar. Instead, you could do what’s called cross-over mirroring, a term that means you respond to her movements with similar movements, but using different parts of your body.

For example, if Fred scratches his head, you might scratch your arm. If he clears his throat, you might cough. You might match his breathing—a more advanced technique—with the barely perceptible tapping of your finger on the desk. Using subtle cross-over mirroring helps ensure that your movements are not perceived as deliberate attempts to match his movements.

To find out if it is working, you can test the level of rapport you’ve established by initiating a movement and seeing if your prospect matches you in some way. If that does not happen, keep working at it and test it again.

Let’s finish this section with a chart that covers the three primary representational systems and see how people who are dominant in one communication mode display characteristics that let us recognize them by both behavior and word choice. You can also use the bottom part of this chart to stock up on words and phrases to help you develop rapport with prospects who display visual, auditory, and kinesthetic repsys preferences.