CHAPTER 6

Aligning with the Nature of the Work

When implementing work-life supports, a key factor that must be considered is the nature of the work employees are performing. Work-life supports such as medical benefits or amenities can be easy to apply more equally across workers no matter what their job. However, flexibility of hours or locations for work can be more challenging to provide. This chapter describes some of the situations in which it may be more difficult to provide flexibility as well as creative ways to implement work-life supports despite the limitations.

In my research, I find that work-life supports are significantly more available when work meets certain conditions. I also find that the question of whether work is conducive to more flexible working options can be a matter of perception. It is important here to define terms. Many work-life supports can be available to anyone and everyone on a policy basis. These are policy-related supports such as parental leave or education reimbursement. However, things become more nuanced in the application of the policy. For example, it is straightforward to provide a certain level of educational reimbursement as a work-life support to everyone. It is more of a judgment call—often made by work team leaders—as to whether certain employees or those in certain jobs should be afforded time off to take classes. The real issue in these cases is work flexibility.

LEGITIMATE CHALLENGES

There are some jobs for which it is challenging to provide flexibility. Work that requires an employee to be connected with machines, equipment, or lab supplies that are only available in the building is less conducive to flexible working options. Manufacturing, production inventory control scheduling, engineering, receptionist/concierge, and IT support are examples of positions that may be less conducive to flexibility. Another example is work that requires employees to have regular face-to-face interaction with other employees or with customers in order to get things done.

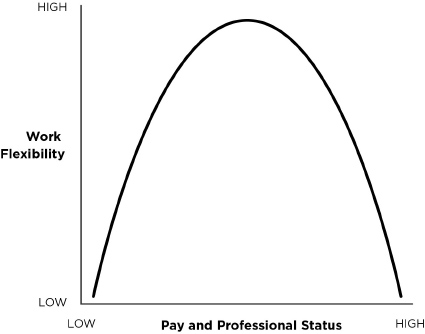

In general, there is a relationship between work and flexibility that can be described by a parabola curve. Employees with the most flexibility afforded to them through their work tend to be those who have medium levels of pay and are at medium-to-high professional levels within their organizations. Those with the lowest pay/professional status and those with the highest pay/professional status tend to have the least flexibility. Why? Because often the jobs at the lower ranks are more tied to desks (such as customer service team members), machines (skilled trades), or customers (repair technicians). At the other end of the continuum are senior managers and executives who must be in the office more frequently in order to lead people in the moment and be available for spontaneous decisions with colleagues. Their face time is usually a part of their work on a day-to-day basis. For every example there are exceptions, but in general, research suggests this relationship between pay/professional level and degree of flexibility available.

Figure 6-1 Work-Flexibility Curve

Barbara, a senior leader at a financial organization, says that traders are required to be at their desks and it feels “nearly impossible” to provide them with flexibility of their hours or the location for their work. Lorraine runs the administrative function for her media organization. Her company has a large contingent of call center employees who are tied to their desks, and to sitting in close proximity to work teams in which problems are solved moment to moment. No matter how strong the will to provide flexibility in working hours, for some jobs it is more challenging than in others.

A major sticking point for one organization—in this case a media company—is the challenge of the “lowest common denominator.” Lorraine’s company is seeking to standardize the employee experience across all jobs and locations for the organization, with equal access to benefits, policies, and practices for all employees. The problem is that a large percentage of employees are technicians and call center employees for whom it is more difficult to provide flexible working options. Unfortunately, this emphasis on equality misses the point. It is certainly possible to offer options that provide equity. Just because every job doesn’t have the exact same access to flexible work options doesn’t mean that equitable solutions can’t be found. If no one can progress until everyone can progress, there is no platform for trying new things and learning. Lorraine is advocating for a shift in mind-set toward equity (not equality) in order to catalyze creative solutions.

CREATIVE SOLUTIONS

Even in situations where jobs are seemingly less suited for flexible working approaches, companies are finding creative solutions that allow for worker flexibility, while ensuring the employees in those jobs are still able to accomplish their work successfully.

TRAVEL

Jobs requiring significant travel present situations in which it is more difficult to provide flexibility. A colleague of mine, Kelly, worked for a multinational legal firm and traveled extensively. Unfortunately, her boss would not allow any flexibility in her schedule when she traveled. Kelly would regularly travel from the West Coast to the East Coast on red-eye flights so she would spend fewer nights away from her children and husband. However, her boss still expected her to show up at the office from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. Sometimes this meant she would have to go straight from the airport to the office at 7 a.m., after having spent a short four-hour night on a plane.

Kelly would freshen up in airport bathrooms and do her best with clients the next day, but it didn’t last. Despite being a successful rising star in the firm, she left and found another firm. Her departure prompted a shift in the firm’s approach to work-life supports. The firm began affording more flexibility of work hours. When staff was traveling, the firm provided one day off per month to compensate for extensive travel. Additionally, the firm provided employees with camera-equipped laptops so they could communicate visually with their families from the road. Unfortunately, it was too late for Kelly to benefit from any of the policy changes at the firm. The lesson here? Creative solutions are usually possible, even in jobs with challenges such as travel. Importantly, leaders must be aware of the constraints of the work they’re requiring of employees or risk losing them.

REGULATIONS AND SAFETY

Another example of work that may be more difficult to accommodate with flexible working choices is that which is controlled by regulations and security measures. One executive with whom I spoke described how certain employees weren’t able to work at home or work on laptops because of the sensitive nature of the data they were handling.

Interestingly, each of these employees was also mandated to take an annual vacation of at least two weeks with no connection to the office. This mechanism was designed to protect against financial fraud. The company believed that any questionable activity in which an employee might be involved would be unsustainable if he was away from the office and completely out of touch for two weeks at a time. The forced vacations had the consequence of giving employees time away.

For employees who must be in the office, and not able to use a laptop for their work, the company is exploring on-site child care so employees can check on their children during the day. The company is also experimenting with creating a partnership with area restaurants, arranging for these establishments to deliver dinners when employees have to work late in the office.

An oil and gas executive with whom I spoke also cited regulations and security concerns as a reason for less job flexibility. He reported that some work was constrained by the unwillingness to load laptops with too much information that could potentially put the organization’s infrastructure at risk. His company began providing each employee with a tablet device on which to perform portions of their work away from the office. By decoupling the work from the device, the company maintained security for the portions of the tasks that were sensitive while creating flexible options for those that were not.

A GENIUS SOLUTION

Recently I worked with a company that set up a new coffee bar within one of its facilities. One of the features designed to support people was a “Genius Bar,” which was a part of the coffee bar. This solution was simply an IT expert who sat at the end of the coffee bar with a brightly colored name tag and a table tent identifying her as the on-duty genius. The concept worked so well during the move in process that they’ve kept it going, and now there is an IT expert at the coffee bar every Monday through Friday from 10 a.m. to 3 p.m. This is a perfect example of a role that is tied to a certain location (the genius/coffee bar) and tied to a certain degree of contact with others. However, while the role has these limitations, it is still possible to provide work-life flexibility to those who perform the role. The way the job is designed—with a trio of employees serving in the role of “Genius on Duty,” instead of one person—there is plenty of flexibility for the people who are part of the genius squad.

CYCLES OF WORK

When companies seek creative ways to accomplish flexible work, the cycles of that work are also important to consider. I worked with a marketing team within a large consumer goods organization. A key part of the work in what was known as the “creation center” was designing, developing, and producing graphics and packages for the organization’s customers. In this case, there was a need for the team to be together at certain times to brainstorm the unique ideas that would drive the package. In addition, there were times when team members needed access to the specialized production equipment and times when the team needed to be present to assemble materials. The work team leader was able to offer plenty of flexibility to each team member by discerning the moments when face-to-face work or on-site work was necessary. When it was, the team was there contributing. For the times when work on site wasn’t necessary, the team had plenty of flexibility to come and go, as long as the work was accomplished effectively.

CYCLES OF COLLABORATIVE AND INDIVIDUAL WORK

When companies are designing and provisioning for work-life supports, they also benefit by assessing the dynamics and cycles of teams, because work sometimes changes at various points in the team’s cycle. Consider two dimensions: relationship and task. At the outset of a project, there is frequently a need for face-to-face, in-office collaboration in order to establish task-oriented starting points such as ground rules, protocols, direction for the team, assignments, working agreements, and key milestones. Once these foundational elements are in place, it is possible to proceed more effectively. In the example of the marketing team above, there was a need for face-to-face collaboration at the outset of each mini-project to establish unique ideas that would drive the remainder of the project.

There are also key moments that require more face-to-face communication and collaboration that are driven by the team’s need to manage relationships. In general, when team members do not yet know each other well, more face-to-face collaboration is useful. There is a degree of trust that is built through face-to-face connections that helps the efficiency and effectiveness of a project as it moves forward. Trust may also be established through virtual means for team members who aren’t in contact with one another in the same location. There may be moments when the team receives new members or members change. There may also be a point where a new leader takes over, or a point where conflict has occurred and must be resolved. These key relationship points require greater face-to-face communication in order to reinforce interaction norms, work through challenges, pick up nonverbal signals, and deal with disagreements in a constructive way. It’s not that these processes can’t occur without face-to-face communication, it’s just that face-to-face processing makes it more effective.

CUSTOMER-FACING WORK

Customer-facing work is another example with requirements that affect a company’s ability to offer flexible working hours. When team members must meet with customers at certain times—either on the phone, on site, or at customer offices—flexibility is clearly more challenging. However, with proactive planning, when work team leaders can identify portions of a day or portions of a week during which this customer work is necessary, flexibility can be available for the portions of the day or week that are not customer facing. Some leaders are also experimenting with providing rewards and recognition for employees who are tied to customer schedules. In one example, a company provides a yearly retreat to a nearby water park for employees and their families.

PROJECT-BASED WORK

One of the trends on the horizon is the “Hollywood Model.” As it relates to the way people work, this means that much of our work—both inside and outside of organizations—will be project based. The “Hollywood Model” derives its name from a comparison with the way movies are produced. A group of individuals gets together for a time-limited duration to produce a movie. When the movie is complete they disband, and each moves on separately to a new movie.

This is distinguished from a typical corporate model, in which people take jobs within departments and work as members of a team for the long term. Work in the corporate model is more continuous and not based on the episodic nature of projects. In the newer Hollywood Model, projects may be for the long term or for the short term, but they are the organizing feature of work. Work is organized to a lesser degree by functions or departments. A worker may still bring a core competence in accounting, but her work is focused on XYZ project. When XYZ project concludes, she is assigned to a different project or must find the next project herself. The implications for this type of approach are far reaching.

In this project-based reality, workers’ identities will be based on the projects they are part of more than the department to which they belong. Workers will potentially have less job security in the traditional sense. At the conclusion of a project, a worker may have to find another assignment based on his merits and reputation. This denotes more of an “independent agent” (find your own work) type of world, even when the worker is still a regular full-time employee of that organization.

This type of model also has implications for the work itself. The leader will either need to contract with the agents on the project to stay until the end of the effort or create a fulfilling enough experience that workers want to stay on the project and see it through to the end. If companies are managing work effectively, they are making work its own magnet, so this model drives to that type of management.

For particularly progressive companies, the Hollywood Model may already be reality. In other cases, the Hollywood Model is taking hold within the ranks of external contract labor. In this case, contractors may trade off the training, development, and insurance benefits a corporation provides in exchange for greater autonomy, freedom, and creative license for their work. In a world where there is heavy competition for talent, companies must either find a way to compel loyalty or create situations where it isn’t necessary. The Hollywood Model suggests a way to leverage loyalty for the short term of a project. This benefits the organization. Career coaches recommend that each worker think of her career as a portfolio of contributions through which she creates value and generates new knowledge for herself and her organization. This knowledge is portable to all future projects and roles, whether the worker is an employee of the organization or a free agent.

LEADERSHIP LESSONS FROM PROJECT-BASED WORK

What are the leadership lessons from the Hollywood Model as they relate to work-life supports? First, leaders must ensure that employees have a strong sense of identity associated with the work they do. Whether people are working in a more traditional team with a more traditional schedule or working in a less traditional way with a less traditional schedule, a strong sense of purpose and identity with their work will be helpful in creating a sense of fulfillment.

Another lesson from the Hollywood Model pertains to passion. In this model, workers have some degree of choice regarding the content of their work and how it aligns with their passions. Finally, there is a strong aspect of accountability in the Hollywood Model. Workers are held accountable by the team leader and by the other project team members. Employees’ currency is the value they bring to their work, and success on a project helps drive the worker to the next project aligned with his passions. Leaders who are able to provide identity and purpose in the work, align people and their passions, and ensure accountability are able to increase an employee’s sense of capacity to fulfill demands and reduce the perception of demands as well. Each of these contribute to work-life support overall.

Previously, I described the importance of employees’ perceptions of capacity in relationship to demand. When a worker faces daunting demands, his perception of his own capacity has an impact on his ability to meet those demands. When the load feels too heavy to carry, he won’t pick it up. Work-life supports, implemented successfully based on the considerations in this model, work on both sides of the equation. They reduce the demands that workers face.

Successful implementation also works on the capacity side of the model. Providing work-life supports increases workers’ capacity to face challenges. Through these solutions, companies can accomplish better results in ways that allow flexible options for employees. Embedded in many of these solutions are self-determination and autonomy through which employees are making choices regarding how they work, when they work, and where they work, within the context of delivering results and meeting the requirements of their jobs.

PERCEPTIONS AND MIND-SETS

Often, the question of which jobs are more or less conducive to work flexibility is based on personal perception. Such a perception is easy to hear in these comments, from a senior executive in an oil and gas company: “Few of our employees can work from home because our work is in the building.” His statement makes a generalization affecting the jobs of literally thousands of workers within his organization and demonstrates a more traditional attitude toward work. In shifting perceptions and in taking steps to provide workers with flexibility, it is useful to think of a continuum. While there may be jobs and situations that are, by definition, less flexible, there are plenty of jobs in which some flexibility is possible. Providing flexibility should not be a yes or no decision, but rather a decision of degree.

Organizations can and should adopt a mind-set of openness toward work flexibility. These overall beliefs can then guide the ways in which organizations experiment with flexible working approaches. Here are some starters: Our organization sets out to provide as much flexibility as is possible and reasonable. Our organization aligns flexible options with the nature of the work. While every job can’t have total flexibility, most jobs can have some flexibility. These types of mind-sets point the way toward creative solutions. Despite all of the situations in which providing work-life supports and flexibility are challenging, leaders can find ways to provide work flexibility. Creative solutions provide flexibility within limits and boundaries of many jobs. Organizations must expand work-life solutions beyond simply considering work hours and location. As we’ve seen, work-life supports come in many forms from benefits to education, and from recognition to project selection and amenities.

IN SUM

Some work is more difficult to accommodate with work-life supports, but it is important to consider the limitations leaders may be imposing based on personal opinions. Whether the work situation is limited by travel, by collaborative needs of teams, or by some other parameter, creative options for work flexibility are usually possible to find.