CHAPTER 12

Aligning with Performance

Companies that are most successful in implementing work-life supports ensure they are creating environments where success is measured based on outcomes and performance, rather than simply on employees’ physical presence in the office. Before technology allowed employees to work anywhere, traditional management often focused on the number of hours spent in the office. Did the employee come to work each day? Was he on time? Did she focus on her work while she was there? As companies seek to implement work-life supports, flexible working options are often where they begin.

While work-life supports include significantly more than flexible working, alternative working arrangements are most germane to the challenge of managing performance. Why? Because flexible working places pressure on leaders to lead and manage differently, as the metric for performance must go beyond an employee’s physical presence. This chapter addresses the need for leaders to focus on outcomes. It also addresses factors that contribute to performance in the first place—such as matching jobs with the right people, and developing and rewarding positive performance.

MANAGING FOR OUTCOMES

“Whites of the eyes” management is when leaders expect employees to be in the office regardless of the nature of their work, or when an organization uses the number of on-site hours as a barometer for employees’ success, rather than evaluating the results they achieve. A company with which I consulted had a “whites of the eyes” culture that gave rise to plenty of legends. One of the stories was that its senior executive team tracked what time people left the office at the end of the day. Before the company had a badge tracking system installed, the executive assistants, whose desks were situated close to windows overlooking the main exit, would monitor people leaving. Toward the end of the day, they would take careful note of which employees were leaving early, which left at 5 p.m., and which headed home later than 5 p.m. Those who left later were viewed as superior performers with more commitment to the organization.

In addition to leaving later in the evening, employees could also gain favor by regularly working on Saturdays. Another story has arisen, now that the company has its badge tracking system installed. People say that employees show up on Saturdays to earn positive regard. However, an enterprising employee has discovered one remaining door that was not connected to the badge tracking system. He and a handful of other employees have devised a system where they enter every Saturday morning through the main door and leave immediately through the unconnected door. Voilà! Freedom. Employees have invested time and energy into playing the system. Imagine what they might have been able to accomplish if that same time and energy had been devoted to the substance of their jobs.

While this style of eyeball management is prevalent in some organizations, the majority of the executives in my study see the need for focus to be placed on productivity. Linda, who participated in my research and who is the general manager of her global technology company’s software division says, “The bar needs to be on productivity and innovation, not time. This is hard to measure, but you don’t want to work more hours, you want to work better, smarter. That requires breakout thinking to set the bar differently.” Rita is chief diversity officer from a global consumer brand. She says, “I don’t care if people are working upside down in the bathtub at home as long as they’re exceeding their objectives.” Diane, an EVP in charge of administration for her global media company, expresses this sentiment regarding the need to produce results: “It’s a two-way street. The employee has to be doing his share and more and then we’re really supportive of flexible working arrangements.” One of the gentlemen in my study had this to say about the trust related to flexible working, “If you trust your employee, you shouldn’t have to ask where he is. If you don’t trust your employee, he shouldn’t be working for you.”

What is striking in all of these comments, in addition to their emphasis on results, is that they position work-life supports and flexible working as privileges. Work-life supports are provided as a result of employees who exceed expectations. The assumptions all of these executives make is that it is appropriate to provide work-life supports in exchange for superior performance. There is a principle of exchange—the employee will receive the privilege of working alternatively in exchange for performance—and not just average performance, but superior performance. Again, this is an example of employees purchasing flexibility with many hours of work and superior performance.

Any employee for whom working outside the office is a consideration should already be a strong performer. If an employee is new or not yet proven, or worse, if an employee has a performance problem, it is not wise to provide him with the option of working away from the office. Flexible working is most effective when it is available to employees who are already performing well and have the skill sets to manage their work successfully. If an employee doesn’t have those skill sets or that maturity, it is wise to build the skills first, ensure good performance, and then layer on the option for flexible work.

MATURITY MATCH

Many employees demonstrate superior performance within the framework of flexible working options. In fact, a recent Gallup report1 found that remote workers logged more hours and were more engaged than workers in the office. In addition, a recent study by Nicholas Bloom found that call center employees who worked at home completed 13.5 percent more calls than those in the office, were less likely to quit, and were more satisfied.2 Unfortunately, not all employees are performing this well. Employees must be mature enough, disciplined enough, and have enough integrity to be effective with flexible work.

I once consulted with a department that was seeking to build a new capability within the organization. Its team was distributed globally and many of its members were remote, working from home full time. The leader of the team had a significant number of people reporting directly to him, and there was very little structure. He believed in meritocracy and having the best person win with little role clarity or boundaries between jobs. This created a negative, overly competitive culture. The leader wanted to connect with the team regularly, so every other Friday he would hold a conference call with the approximately one hundred team members who were on the extended team. One of the team members would sometimes fall asleep and snore during the call. Another of the team members would brag that he regularly took long, relaxing baths during the calls. This type of behavior was unacceptable and demonstrated a lack of personal maturity and disregard for the team. These were not ideal candidates for flexible work.

One of the interviewees in my research also shared the story of an operator in a call center who has since lost her job. At the time, the company was running a pilot to explore whether call center operators might be able to work at home. This particular call center operator was caught by her supervisor doing laundry during calls with customers. The employee believed she was successfully multitasking, but the supervisor, who would regularly listen in on calls in order to check quality levels, discovered that her laundry activities were audible to the customer on the other end of the phone. The pilot was terminated and call center operators were not permitted to work from home. This one team member prevented the rest of the team from benefiting from alternative work solutions. Barbara, head of human resources for her global banking organization, discusses the importance of considering whether specific employees have the appropriate skill set to work outside the office: “Not every person is wired to work at home. Not every person is mature enough.”

The lesson here? Ensure that there is an appropriate personal maturity level and discipline on the part of any employee who is approaching a flexible working program or an option for working at home. Pilot a process to see if it works. Find ways to hold people accountable for flexible working in the same way people are held accountable for their work in the building. These examples are extreme cases, but they are indicative of the need for selection and accountability for those who have the options for flexible working models.

SITUATIONAL MATCH

Another factor in an employee’s performance is the extent to which his situation—not only in terms of maturity, but also in terms of his home office or child care—makes it possible for him to work productively when he is not in the office. I consulted with a company that was going to be closing field offices. The company was experiencing a decline in orders and needed to reduce costs. One of its cost reduction strategies was to close smaller offices. The company sent people home, but many workers did not react positively. Some employees didn’t want to work from home because they didn’t have space for a home office or because they had children at home during the day. Other employees strongly preferred the companionship and camaraderie that the office provided. Finally, there were employees who just didn’t trust themselves to be home and remain focused on work.

Unfortunately, there were no other choices at the time. For employees who faced issues with space or child care, the company outfitted their home offices with furniture and educated them on how to set boundaries with their families. The organization also created opportunities for colleagues to come together in third places such as local coffee shops so they could regularly connect and collaborate in person. The company also provided training in the areas of organization and time management. Perhaps most importantly, the company coached leaders, teams, and individuals on how to manage daily, weekly, and quarterly goals so that physical presence was less critical to success.

KEEPING THE DOOR OPEN

When employees do work away from the office, it is valuable to keep doors open—going both ways. Sometimes employees are working in the office and want the option to work from non-office locations. In other cases, employees have attempted to work in third or fourth places and have determined it wasn’t effective for them, and have wanted to return to the office. Sometimes employees begin an education program and determine that working away from the office is too much to handle. In these cases it is helpful for leaders to have an open door for discussions and adjustments.

JOB MATCH

Another factor in performance is the employee’s fit with the job she is in. Previously, I covered the requirement to match the nature of the work with the work-life support that is offered. Now, in thinking of how organizations foster solid performance, consider how they match the content of work to the employee. It is useful to do so because when work is well-matched to employee skills and preferences, performance tends to improve and managing performance becomes easier.

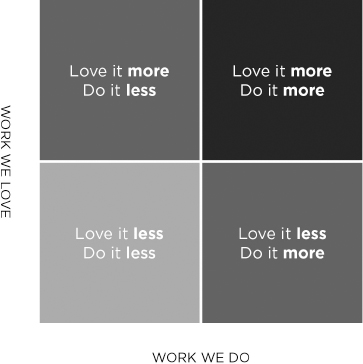

In the 1990s, my company was having a hiring blitz in production. We could not hire people fast enough, so we took an “all hands on deck” approach and recruited everyone with HR skills to interview and select candidates for the open positions. I was a member of the cadre interviewing literally hundreds of candidates during a period of a few weeks. During this time, one of the principles we applied in the selection process was “work we love/work we do.” For each of us, there is work we love to do and work we don’t especially enjoy. Likewise, any job has a mix of work that must be done. We can think of this in a two by two matrix.

Figure 12-1 Love-Work Patterns

The ideal scenario is when we’re in a job for which the required tasks are a match to the activities we love. There will always be tasks we’re less excited to perform, but in the ideal situation, these will be tasks that are less demanded and less frequent in any job we occupy.

Having a good match between the job and the person is one way to create abundance. Leaders are in a position to select candidates based on fit and to help employees find alternative projects or roles when there is not an appropriate fit between the employee and the job responsibilities. Leaders can enhance fit by shifting projects within a job or allowing employees to develop their education. Sometimes, the way an employee is allowed to work—in terms of hours and location—can also improve fit between job and employee. Hence, this is another way leaders can provide for work-life supports. People naturally perform better when they feel a fit with their work,3 and this benefits both the employees and the organization.

SKILL DEVELOPMENT

Another element of positive performance is skill development. Naturally, job performance is better when employees have the skills they need. Learning and skill development can be powerful vehicles to support workers as they face multiple demands across work and life. As work changes continually, so do the skills necessary for success in a job. An employee also needs certain skills to work successfully away from the office. At the top of the list are the ability to communicate, the ability to collaborate both physically and virtually, the ability to manage time and multiple deadlines, the ability to organize work and follow through to completion, and the ability to build trusting relationships with others. Development approaches must fit into a framework of clear goals and objectives.

Companies vary widely in the extent to which they offer formal learning opportunities for employees. Some companies hold orientation at the start of employment and rarely thereafter. Other organizations conduct training for all employees on a frequent basis. In any case, it is rare that companies conduct learning opportunities specifically on the topic of work-life supports. Rick Wartzman, executive director of the Drucker Institute, weighs in on training and learning:

Much of the business world now centers around the activities of “knowledge workers”—a term Peter Drucker coined in the late 1950s. Knowledge workers have the fortune of not being tied to a clock or an assembly line. For them, work and life automatically bleed together, and should bleed together, as never before. One aspect of this is the need for lifelong learning. Over the past thirty or forty years, corporations have added a host of training programs and provided incentives for people to further their education. In fact, in many ways, companies have become the major providers of continuing education in this country; their investment has risen markedly, even in inflation-adjusted dollars. Lifelong learning is a huge piece of what Drucker would prescribe, particularly for support of knowledge workers and particularly in this day and age when knowledge becomes obsolete very quickly.4

K.H. Moon has been globally recognized for his commitment to lifelong learning when he was at the helm of Yuhan-Kimberly in Korea. Moon offered learning during working hours, for up to 360 hours of professional and technical skills learning per year. In contrast with other organizations which offered compulsory training and required testing, Moon’s company offered voluntary training. These classes covered topics such as internet skills, parenting skills, and English and Chinese language skills.5 Moon provided learning through multiple forms, offering more than simply classroom options:

We also offered company-borne study groups. Necessities like books and professors were paid for by the company. The learning was available through a “learning cafeteria concept” in which employees could choose their own menu of learning. We also asked employees to identify three to five topics they were interested in and wanted to speak about in front of others. Through this process, employees became facilitators of classes for others and we had hundreds of mini-classes we offered. Because I didn’t want to lay off workers during the financial crisis, I implemented a system where they would work for three days and then have three days off. During their three days off, employees could take advantage of these learning opportunities.

Under Moon’s leadership, Yuhan-Kimberly saw tremendous results:

Employees became multiskilled, cross-functional, cross-boundary, and cross-border. They were able to cope with ever-changing work, technology, and processes. This allowed the company to accelerate the speed to market. While our competitors had scale—for example, P&G was ten times our size—we were able to win with speed. Our competitors would typically take three years to bring a product to market. Our average was nine months. Ultimately, we forced P&G out of the market entirely. This was because of our speed and agility, fueled by employee learning. Employees also became better overall. They were able to contribute more fully to their families and their communities.6

DEVELOPMENT PLANNING

Learning and development are most effective when they are targeted for employees’ specific goals and unique needs. A development plan is a critical framework for an employee to pursue the most appropriate learning, aligned with the needs of the job and the company. Xavier Unkovic, global president of Mars Drinks, Inc., addresses the importance of training and managing based on desired performance outcomes:

First, we communicate the vision for the company and ensure clarity of vision and goals and allow people to express themselves. In this way, they know what this company is doing and how they can contribute. An organization also needs the right programs and tools in order to develop people successfully. We have HR support and also strong management, which are key for us to own associate development. Development is important for any position or role in the company. We need to celebrate all roles. With the associates, our managers have clear responsibility for their team and engagement. We are making 100 percent of our associates have a documented development plan. It is a seventy-twenty-ten development plan: 70 percent learn by doing, 20 percent learn by coaches, 10 percent learn by education.7

The connection between development programs and performance planning is a must. At Mars, associates around the globe are involved with a Mars University program which teaches critical skills. The company also utilizes a seven-part development plan which clearly defines goals for development. The company’s belief is that this formality helps ensure effectiveness for employees and for the organization. Has Mars seen results from its commitments to performance planning and development? Xavier says “yes”:

Performance will come if you develop your people. This is also related to retention. People will be more likely to stay with the company when they have the opportunity to develop and contribute.

Even with all the positive results from development planning and learning, one caveat to remember is that training by itself won’t change behavior. It is important to determine whether there is a gap in an employee’s knowledge or skills before offering training. Frequently, training is implemented as the solution to a problem for which the root cause is lack of motivation, not lack of skill. Training is the appropriate solution when the participant truly needs or desires more knowledge or skills; otherwise, the development efforts will not be effective. Development is most effective when the employee has accountability and takes responsibility for accomplishing his goals. This ownership provides a level of self-determination in how the employee learns, on what timetable over his life course, and on what topics. Self-determination and control are critical elements of work-life supports and of bringing work to life.

MENTORING

In concert with formal learning, either in the classroom or on e-platforms, mentoring can be a valuable tool for knowledge and skill development and behavior change. Progressive companies are carefully selecting mentorship relationships and building mentorship processes into their organizations. Companies are identifying the “organizational heroes” who most embody the desired culture and matching them with high potential employees. The expectation is that both will benefit from a personal relationship as well as coaching and feedback.

MISTAKES AND REWARDS

When offering formal training, development, and mentorship, learning-oriented organizations also embrace mistakes. Curt Pullen,8 president of Herman Miller North America, offers this perspective on learning-oriented organizations and their approach to mistakes:

In the room where my team meets regularly, I have a saying framed and hanging on the wall. It says, “Let’s make better mistakes tomorrow.” This attitude toward mistakes is about learning. Generally, we learn more from our mistakes than from our successes. We can take our successes for granted, but when something doesn’t work out, it causes us to study what went wrong. We go back and examine how we could have done things better. For this reason, mistakes provide a tremendous learning opportunity. When we take a learning approach, it sends a signal to the organization that also relates to decision making. People need to make choices and decisions. If the leader makes all the decisions, there is less opportunity for learning. If people make the decisions, they will own them and the outcome will be something we can all learn from. As leaders we need to back people when they make decisions. In addition, when people own their decisions, and can describe what decisions they’ve made and why they’ve made them, it provides the opportunity to increase our collective knowledge. If people are in fear, they won’t feel free to make decisions. Decisions need to be made in a context of learning and of leaders who support the decision making of people around them.9

Learning and development for leaders and all employees is most effective when it is iterative. Mistakes allow for this iteration. Try, learn, and try again.

ACCOUNTABILITY AND RECOGNITION

When employees perform well, rewards, awards, and recognition are an important type of work-life support. Recognition goes hand in hand with accountability. It is impossible to provide substantive recognition without holding employees accountable. Why? Truly meaningful recognition is specific to a result. It goes beyond a leader saying “great job.” Recognition is most powerful when it demonstrates that the leader is knowledgeable about the employee’s specific performance and accomplishments. Recognition by peers is also motivating and fulfilling for employees. Mars has an awards program that provides the opportunity for peers to appreciate and recognize one another. Xavier Unkovic, global president of Mars Drinks, Inc., says:

We have a recognition program called “Make a Difference,” in which associates nominate each other for awards. We had over 26,000 associates nominated last year. This means that one-third of our entire population was recognized by their peers. We have 16,000 associates who donate over 40,000 hours to their communities through our Mars Volunteer Program (called MVP).10

What motivates people to make the effort? Xavier says it’s intrinsic.

There is no financial reward. It’s not about the prizes. It’s about how you as an individual have put a principle into action, and the intrinsic reward that comes from that. The awards are related to people, performance, and planet, and it’s about how you were able to affect these. When people have the freedom to act they can find ways to make a better company and they generate fantastic ideas.

Another company, Etsy, an online marketplace for handmade and vintage goods, provides a different example of a formal process for recognition. There, each employee has the opportunity to recognize another by e-mailing the Ministry of Unusual Business, which delivers small gifts or cards to the employee being recognized.11 Rewards and recognition are elements of work-life support that motivate and create the conditions for abundance. This is especially true when they are provided by peers in addition to being provided by the organization.

IN SUM

Work-life supports are most successfully implemented when organizations and leaders focus on performance, not simply on whether employees are physically present in the office. Sometimes this means dealing with performance issues and ensuring that employees demonstrate a level of maturity and self-discipline. Performance itself improves when employees experience a match between their jobs, their preferences, and their personal situations. Skill development, mentoring, ongoing learning, and recognition also contribute to creating conditions under which employees can thrive and are supported in work and life.