THE S CURVE OF LEARNING

Captain James Cook was one of the greatest explorers and cartographers in history. He was the first European to visit what is now Sydney, Australia. He discovered the Hawaiian Islands and skirted Antarctica, sailing a total of well over two hundred thousand miles—essentially the distance from the earth to the moon. One-third of the globe was unmapped when he was born; when he died in 1779, he had explored most of it and drawn maps so accurate that they were still in use two hundred years later.1

It’s unlikely Cook would have accomplished any of this had he not been willing to jump to new learning curves and been sponsored by people who recognized and invested in his talent.

Cook was born in 1728 to an impoverished laboring family in Yorkshire, England, and raised in a tiny hovel where only one of his five siblings lived to adulthood. The lord of the local manor, Thomas Scottowe, recognized James as gifted and paid for him to be educated at the local school. At seventeen, Cook moved to the coast of the North Sea, and thanks to his patron’s recommendation, he secured a job as an assistant shopkeeper.

When the sea called to him, Cook found a mentor in James Walker, a ship owner and coal merchant, who took Cook on as his apprentice. Under Walker’s tutelage, he worked his way up the ranks of the merchant navy, while studying mathematics, navigation, and astronomy.

In 1755, Walker offered Cook the position of ship’s master. Instead, he chose to join the Royal Navy where he began as a common sailor. (With a war in France looming, he believed this step back would lead to opportunities for promotion.) Here he found another patron in Hugh Palliser, an aspiring officer who was impressed with Cook’s talents and brought him along as he ascended within the naval establishment.

Cook’s mapmaking skills and his leadership during the Seven Years’ War eventually earned him the command of the HMS Endeavor, the Royal Navy research vessel he would captain on his legendary voyages.

Cook’s success depended on three men—Scottowe, Walker, and Palliser—who recognized his gifts and helped develop them. Without these talent-spotting sponsors, instead of becoming a revered adventurer, he might have wasted away in obscure poverty.

Captain James Cook wrote in his journal that he had “sailed farther than any other man before me.” Captain James T. Kirk, the pop culture icon of Star Trek, is modeled on Cook, and his motto “to boldly go where no man has gone before” could easily have belonged to Cook.

This is what people want on the job: to boldly go where they haven’t gone before. To venture into uncharted territory. To take themselves and their company where they’ve never been.

And yet, we humans also like a certain amount of predictability. If given the chance to see our future in a crystal ball, most of us would peek. We like to flip a switch and the light goes on. When we can forecast the future, we elevate our sense of security. When we believe we control our circumstances, we feel more confident. Even millennials, who often hummingbird from one opportunity to the next, believe that sticking with one company and climbing the corporate ladder is a safer bet for salary growth than switching jobs or entrepreneurship.2 But, control is an illusion. None of us knows what the future will bring.

It’s a conundrum. Disruption fosters innovation. It also challenges current, and often dearly held, practices without providing clear alternatives. It’s especially murky when it comes to finding the best way to manage your employees.

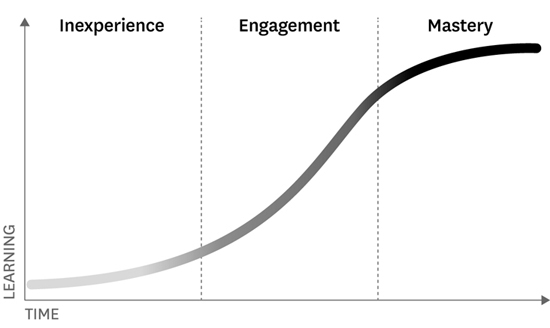

This is where the S curve model comes in. At the Disruptive Innovation Fund we employed an S curve model, popularized by sociologist E. M. Rogers, in our investment decision making. In investing, the S curve model is used to gauge how quickly an innovation will be adopted and how rapidly it will penetrate a market. The S curve helps make the unpredictable predictable. At the base of the S, progress is relatively slow until a tipping point is reached—the knee of the curve. This is followed by hypergrowth up the steep back of the curve until slow growth occurs again, as market saturation leads to a flattening top of the S. (See figure 1-1, “The S curve of learning,” for a visual representation.)

FIGURE 1-1

The S curve of learning

The S curve model also helps us understand the development of and shifts in individual careers. S curve math tells us that the early days of a role, at the low end of the S, can feel like a slog. Cause and effect are seemingly disconnected. Huge effort yields little. Understanding this helps avoid discouragement.

As we put in days, weeks, and months of practice, we will speed up and move up the S curve, roaring into competence and the confidence that accompanies it. This is the exhilarating part of the S curve, where all our neurons are firing. It’s the sweet spot.

As we approach mastery, tasks become easier and easier. This is satisfying for a while, but because we are no longer enjoying the feel-good effects of learning, we are likely to get bored. If we stay on the top of a curve too long, our plateau becomes a precipice.

Everyone Has an S Curve

In one of my facilitated sessions, a CEO said to me, “Eighty percent of my people don’t have an S curve. They just don’t care.” I could hear the frustration in his voice; it was real. But his claim wasn’t true. There are different types of curves and factors that can affect them, but everyone has an S curve. And throughout a career, most of us will discover several or even many of them.

If employees “don’t care,” it doesn’t mean that they don’t have an S curve—it means they are disengaged. Nearly every human being is on the lookout for growth opportunities. If a person can’t grow with a company, they will grow away from it. As with any rule, there are exceptions. Some are people who won’t grow, no matter how you try to help them. But what about past high performers who are currently underperforming? If it’s time to jump, and they won’t, you may need to give them a nudge.

Think of the leaven in bread: a little bit is all it takes for the whole mass of dough to rise, but let it rise too long and it will collapse. The energy of the chemical reaction will have spent itself. The key is to capture the leavening at the right time, bake our loaves, and reserve some “starter” for the next batch. The energy of your employees is there waiting to be tapped. But they will need to start over regularly. Ensure that they can, and they will provide lift to your organization—and do it over and over again.

Saul Kaplan, founder of the Business Innovation Factory, once told me, “My life has been about searching for the steep learning curve because that’s where I do my best work: swinging like Tarzan from one curve to the next.” This is true for most of us. If we want our employees to keep working at a high level, the S curve management strategy is key.

An A-Team Is a Collection of Learning Curves

Just as an investor’s portfolio has diversified holdings (e.g., you don’t put all your money into a single company), your team should include employees who are at different phases of development. Visualize your team as a collection of people at different points on their own personal S curves. Aim for an optimal mix of low-, middle-, and high-end-of-the-curve employees: roughly 15 percent at the low end, around 70 percent of the team in the sweet spot middle, and 15 percent at the high end of the curve.

Assume that new team members will be at the low end of their curve for approximately six months—although this will vary, of course, depending on the difficulty of the role and the aptitude of the individual. At the six-month mark, they should be hitting the tipping point and moving onto the sleek, steep back of their learning curve. During this second phase, they’ll reach peak productivity, which is where they should stay for three to four years. At around the four-year mark, they will have made the push into mastery. In the mastery phase, an employee performs every task with ease and confidence. This top-of-the-curve, high-ender can mentor new team members who are surfing the low end of the wave. But ease, and even confidence, can quickly deteriorate into boredom without the motivation of a new challenge. Before long, it will be time for them to jump to a new learning curve.

Mapping Your Team’s S Curve

We’ve developed a diagnostic tool to help you determine where you, your team members, and even your potential hires might fall on an S curve. The S-Curve Locator (SCL) is available on my website at (whitneyjohnson.com/diagnostic). It’s helpful for each team member to see if the results square with what they expected. If they don’t, it’s useful to ask why. The aggregate results, from a managerial standpoint, provide a snapshot of latent talent and capacity for innovation.

Consider a global health care company. After administering the SCL to nearly one thousand employees, we found that around 5 percent were at the low end of the curve. This phase is characterized by a high degree of challenge, intense stretching, and personal growth. Seventy-one percent of respondents fell into the central portion of the S curve, indicating that they were challenged, with room for continued learning and growth. One-quarter (24 percent) of respondents were at the high end of the curve, suggesting a level of mastery that may demand a new opportunity to help them stay engaged. While a manager could be forgiven for thinking that’s a good thing, 24 percent is too high in my experience. These valuable employees have moved beyond the sweet spot into a potential danger zone. Most of them didn’t want to leave the firm for something new. Most expressed excitement about the company’s mission and values. But 40 percent of the employees were feeling under-challenged. For a manager, this is an important data point. If you have too many people at the high end, it’s a surefire sign that you are at risk of disruption. People at the high end of the curve may be high performers, but if they stay there too long, they will get bored, and leave, or become complacent. Companies with bored and complacent people don’t innovate; they get disrupted. On the flip side, a large percentage of people at the high end of the curve presents an opportunity: to capitalize on innovative capacity lying dormant.

By contrast, at WD-40, the company with the amazing engagement scores profiled in the introduction, my assessment produced the balance of numbers we would anticipate from an engaged workplace: a small number (5.6 percent) of employees scored in the lower range of the diagnostic, indicating that they may be dealing with the high-challenge portion of the S curve and the struggle to gain competence. The majority (88.3 percent) fell within the sweet spot of high engagement and productivity, indicating that they are learning, feeling challenged, and enjoying growth in their present role. A relatively small number (6.1 percent) of employees are operating at the higher end of the S curve, indicating a level of mastery that may require a new, more challenging path. An additional 5 percent of people were closing in on this mastery stage.

To be clear, not all employees on the high end of the S curve will need to jump. While some high-end employees may have fallen into a rut of complacency and entitlement, some may be able to stay in their current role longer if given stretch assignments. Especially in intellectually rigorous fields, where it may require years for true mastery. So long as we are aware that tedium can undercut performance, we can watch for signs that an employee needs to jump. We’ll talk more about the high end of the curve in chapters 6 and 7.

Chess, Not Checkers

Chess is the quintessential strategic game. Instead of having one type of playing piece on the board that represents you, there are many—there’s a whole team. Unlike in checkers, in which many pieces on the board all do the same thing, chess pieces are defined by specific roles. They are designed to move differently and yet work together. A good chess player both understands the individual moves of different pieces and knows how to deploy them in complementary ways.

As leaders, we see the whole board and understand the roles of different individuals. The team objective is achieved when we optimally coordinate these people’s roles, always visualizing several moves ahead.

Of course, there are a few flaws with this analogy. The people we employ are not inanimate objects but rather free agents—free to leave our board and go play for someone else. Nor do they have a limited set of prescribed moves. The roles they fill may initially provide an opportunity for them to contribute but may ultimately become limiting. Within an S curve is potential, but eventually that potential is exhausted. As managers, we want to recognize when someone who has been functioning in one role is ready to try something new. Consider the pawn that makes its way across the board and is rewarded by becoming a queen. It’s a powerful augmentation of the pawn’s abilities—and of the chess player’s options.

Jim Skinner, former CEO of McDonald’s, is a good example of such a “pawn.” Skinner completely lacked the standard CEO credentials. He didn’t have an MBA—he never even graduated from college. His first job was flipping burgers. But over four decades, he was able to assume a variety of roles that eventually led to the C-suite. When his predecessor stepped down due to health problems, he got the top job. McDonald’s did well during his tenure, but Skinner’s most enduring contribution may be his emphasis on talent development. Perhaps because he didn’t have college credentials himself, the training and development of his employees was something Skinner took very seriously. He created a leadership institute a year after he became CEO and required that all executives train at least two potential successors—one who could do the job today, the “ready now,” in McDonald’s parlance, and one who could be a future replacement, the “ready future.”3

Limiting people to certain roles or positions holds no benefits for your business. Be the chess master that provides vision and coordination while allowing pieces to move themselves. Alan Mulally, former CEO of Ford, began his career at Boeing. A strong performer, he had been promoted from individual contributor to manager. After a few months, one of Mulally’s direct reports, a talented engineer, announced he was quitting. When Mulally asked why, the engineer said, “You micromanage. You’ve made fourteen changes to my work. Your job is not to do my job. Your job is to help me understand the bigger picture. Plug me into the network. Advocate for me.” The employee still quit. Mulally, who went on to be one the best CEOs of our time, apparently learned his lesson.4

Eager, capable employees tackling new challenges are a key driver of innovation within an organization. Author Alex Haley once said, “When an old person dies it’s like a library burning.”5 When employees leave a firm, books burn: we lose a wealth of vital institutional knowledge and expertise. Let’s not be the innovation book burners in our organizations.

What You Measure Matters

We tend to want or even expect the development work to already be done when someone enters our employment. Why then would we reward people who focus on developing talent? We wouldn’t. With expertise as a given, we focus on numbers and are rewarded for doing so. Just look at the metrics. Number of widgets sold: check. Number of clients or customers called: check. Number of people developed? None. Number of people poached? None. These metrics aren’t considered. Instinctively you know they should be, but you still ignore them. It’s no wonder we’re reluctant to reward managers for the development of resources that happen to be human.

If we are to embrace the power of personal disruption through carefully orchestrated jumps to new S curves, we’ll rethink the way we evaluate those who manage the takeoffs and landings. A simple start is to create metrics that reward talent spotters and developers. Jo Taylor, director of Let’s Talk Talent, a talent-management consultancy, shared several ideas that she applied during her three-year stint as director of talent management at Talk Talk, a UK-based telecom. “Include talent development in senior managers’ performance review matrix, and tell them that a percentage of their bonus is going to be payable only if they’ve developed their people. You can measure that through 360 reviews from direct reports. Using those reviews, you can also quickly assess which individual managers are doing this kind of development, and focus on those who aren’t with additional training and resources.”

Talk Talk also set a high target for internal mobility within the company: they wanted to see 60 percent of available roles filled internally. The company’s philosophy was that the business—not individual managers—owns the talent, which encouraged and incentivized managers to develop talented people and allow them to move into new roles internally. The stats from the beginning of Taylor’s tenure at Talk Talk compared with the numbers when she left her position suggest that talent development and internal mobility increase employee engagement: internal mobility increased from 35 percent to 50 percent; employee engagement increased from 56 percent to 76 percent; the company’s profitability was up from $1.30 to $3.00 a share.

Another way to figure out who is developing talent is to first analyze who is delivering results, getting promoted, and going on to interesting opportunities, and then ask those people who they work for. If past employees have been more likely to quit than jump to new curves, that’s a danger sign. Management thinker Dave Ulrich said it well: “Instead of asking a multimillionaire how many millions they’ve earned, ask how many millionaires they have created.” For example, Lori Leibovich, editor in chief of the Health brand at Time Inc., has managed and developed several journalists who have gone on to land prestigious jobs in the field, including a writer at large for New York magazine and executive editor at Cosmopolitan, to name a few. This is someone people want to work for. Who in your organization has a track record of apprenticing talent?

When I was an equity research analyst at Merrill Lynch, some great people worked for me. Like Mike Kopelman. When an opportunity arose to work for Jessica Reif Cohen, the leading media analyst globally—she covered companies like News Corp—I suggested and brokered a move for Mike. It was a huge loss to me and my team, but a boon to Merrill Lynch overall. Unlike at Talk Talk, though, talent development wasn’t a metric measured in performance reviews. At Merrill Lynch, managers were developing talent at their own risk. If you want managers to let their people grow, reward them for it.

Hire Self-Starters

Kim Sreng Richardson arrived in the United States from a refugee camp in Cambodia at age twelve, unable to speak, read, or write English. She was placed with nine-year-olds at first but soon caught up and graduated from high school at age nineteen. At twenty-three, she started work at CPS Technologies, a materials manufacturer in Norton, Massachusetts, as an entry-level assembly operator in the factory. After six months, she saw an opportunity to move into quality assurance. She didn’t know anything about Word, Excel, or Access, all of which she needed to complete the inspection documentation. But she was willing to figure them out, and CPS provided training so she was able learn. She says, “When I go to work, I give a hundred percent all the time. I’m hungry. And then I get the opportunity.” This has happened repeatedly for two decades. Today, she runs CPS’s manufacturing operations. CEO Grant Bennett says of her, “Sometimes Kim raises her hand. Sometimes she is tapped. Either way, we always know she will get the job done. She is one of the most capable people I know.”

Richardson’s story highlights an important prerequisite for this personal disruption approach to managing: it only works if you’re managing people who can self-manage. You need people who believe that what they do makes a difference and are willing to hold themselves accountable, independent of constant oversight. Do they arrive on time? Are they prepared for meetings? These are clues as to their level of personal responsibility. An effective manager will want to give such self-starting, self-monitoring, self-governing high performers the opportunity to move to new S curves.

During a restructuring at Novartis, Henna Inam shared with her boss that she had her eye on a general manager (GM) slot. (Restructurings are frequently seedbeds for personal disruption.) As a warm-up, they wanted her to do a rotation in sales, selling Gerber products to Walmart. Her manager for this rotation was Gary Pinkowski. For a numbers-oriented Wharton grad like Inam, Pinkowski’s leadership style was unexpected. During their one-on-one conversations, he asked only three questions: How are you? How are your people? And, How is the business? Pinkowski’s high-level vision and approach were evident in the number (only three) and the tenor (people first and second) of his questions.

Within three years, Inam was up for GM, with a choice of assignments: the opportunity to take over a sales leadership position for Novartis selling into Walmart—a billion-dollar business—or become the GM for Mexico, a $100 million business. The assignment in Mexico wasn’t as high profile, but it would give her the opportunity to run an entire business, including the commercial and R&D (research and development) functions. It would also leverage one of her strengths—cultural adaptability, developed through living in five countries across three continents. She chose the opportunity in Mexico, and in taking on this challenge, Inam now reported to Tim Strong, known for his trusting, hands-off management. Two years later, she had turned around the business in Mexico and was one of ten people out of ninety thousand employees who received an award for her outstanding performance.

Antony Jay, a former BBC executive, posits that retaining high-performing talent relies on the decentralization of leadership. It’s important to encourage employees to be founders in their own space, to give them the chance to make what they will. “The conventional management hierarchy,” writes Jay, “is rather like an enclosed city state: a young manager looks around and sees the mountains that circumscribe ambition.” Circumscribed ambition is a hotbed of disengagement: talented people will either leave or be forced, unhappily, to accept the unsatisfactory conditions that limit them. “Corporation executives may tell you that an organization cannot have too many good managers, but they are wrong. What it cannot do is keep them good without constantly giving them tasks that match up to their abilities.” Assign and reassign “to make sure that staff of high quality stays with the firm—and stays of high quality.”

Managing a team as a collection of individual S curves implies a decentralization of power. People should be able to function independently enough that, with minimal oversight, they can both operate for the good of the whole and make their own fortune. “The real pleasure of power is the pleasure of freedom,” says Jay.6

Think about your best boss. Like Henna Inam’s former bosses, Tim Strong, and Gary Pinkowski, now VP of sales at Post Foods, your best boss made it possible for you to succeed, confident that once you knew the rules, you could self-manage. When you facilitate personal disruption, you build an A-team and become a boss people want to work for. A boss people love.

Summary

The S curve, traditionally used to model the dispersion of innovative goods and services in the marketplace, is also a helpful model for understanding and planning career disruptions.

The S curve represents three distinct phases of disruption:

1. The low end, involving a challenging and sometimes slow push for competence.

2. The up-swinging back of the curve, where competence is achieved and progress is rapid.

3. The high end of the curve, where competence has evolved into mastery and can quickly devolve into boredom and disengagement.

This necessitates disruption to a new curve to reengage and maintain employee productivity. Poor engagement levels are consistently a challenge to business growth and profitability.

Create a team that is a high-functioning collection of S curves, with a small percentage of people at the low and high ends of the curve and the majority in the sweet spot at any given time.

If you'd like more tips on applying personal disruption to building an A-team, email me at [email protected] or sign up at whitneyjohnson.com