CHAPTER 6

Learn from Your Failures

(Do Not Reinvent the Wheel)

Vignette: The Wrong Estimate, Again

He made an estimate mistake. Again.

Francis was the best estimator we had. Whenever a new Request for Proposal (RFP) came to us from the federal government, Francis was the first person to have a look at it and advise management whether the company should participate in the bidding process. This was an important decision because the time and effort invested in preparing a proposal often required a few weeks of professional and management time. We needed to send line managers to inspect the equipment in need of repair or maintenance, estimate the effort that was necessary to make those repairs, evaluate the required material that we needed to purchase, plan for workforce availability, and prepare the bids.

Francis had the last word—a go or no-go decision was based on his expert advice.

Francis kept all the history data of past estimates in his head. It was, therefore, very difficult to compare previous work and build on that experience. Once the bid was submitted, any omission or wrong estimate might affect the project’s profitability if the bid was successful. Very little playroom was left for estimation errors.

The last few projects the company won based on Francis’s estimates were over-budget with lower-than-expected profitability. I wondered why this was happening.

According to Francis, the foremen were to “blame.” According to the foremen, Francis’s estimates were wrong. The blaming game was not productive.

We started by building a database of past estimates, followed by actual project results. An image began to emerge: the older the estimates, the better the results. The most recent estimates gave the worst results.

Francis was estimating based on data that was too old. He needed to update his estimating process and include the foremen in this exercise.

Once this new estimate process was implemented, the bidding process was markedly improved—estimates were again on target.

Collaboration works.

Lessons Learned: Whose Reality Counts?

One has sometimes difficulty relying solely on experience. Is it reliable? Does it still apply to the present processes? When does one need to “let go of the past”?

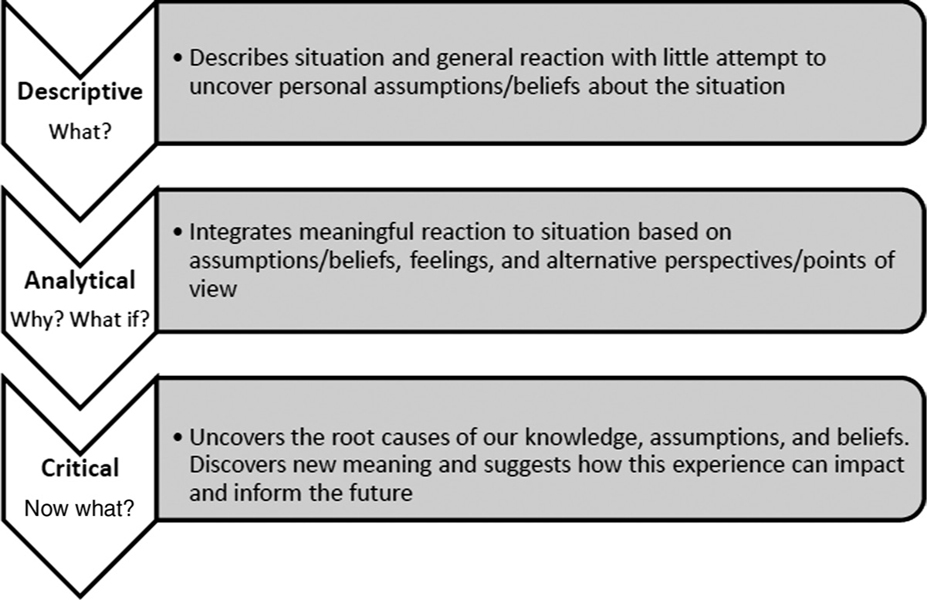

Learning from key events is a constructive learning process sometimes called critical reflectioni by applying a three-staged approach: exploring, reflecting, and projecting.17 The objective is to develop an environment conducive to a more productive outcome.18

Brookfield explains that critical reflection involves three phases:

1. Identifying the assumptions (“those taken-for-granted ideas, commonsense beliefs, and self-evident rules of thumb” (p. 177)) that underlie our thoughts and actions

2. Assessing and scrutinizing the validity of these assumptions in terms of how they relate to our “real-life” experiences and our present context(s)

3. Transforming these assumptions to become more inclusive and integrative, and using this newly formed knowledge to more appropriately inform our future actions and practices

The process of critical reflection may be conceptualized through the descriptions and questions contained in the following figure.19

Learning from experience counts.

Vignette: Make a Decision

“What do you think I should do?” asked Shawn, the plant foreman.

He was referring to the latest incident during last night’s shift. The workers had to prepare the steel for painting. Doing the difficult task of sandblasting prior to painting was always easier during the night because it was more comfortable to use the heavy protective equipment needed for the job. But night sandblasting came with a problem: dew. The shiny metal tended to rust, or in the workers’ jargon, to “flower,” making painting impossible later on. The result was that sandblasting had to be redone to remove this rust before the paint could be applied.

I was convinced that Shawn knew exactly what to do. Still, he was cautious when he had to use his authority with the unionized workforce and wanted a “higher authority” to take the required decision. As the chief operating officer, I was the person to go to.

I was new to the plant, and I was not yet familiar with all the challenges line managers had to face when dealing with the workers. As a seasoned executive, I tended to make snap decisions all the time. Was this an appropriate time to make the decision for the foreman?

I sought advice from some of my colleagues. They suggested leaving operational decisions to the line managers. Shawn had to decide by himself.

Delegate decision making.

Lessons Learned: When in Doubt, Do It Both Ways

One of the key roles of leadership is to position employees in the organization to be successful. This includes the selection, nurturing, and direction provided to employees throughout their careers and tending to their professional and personal needs. Encouraging them to take a risk in making their decisions and supporting them in their actions (when right, with praise; when wrong, with training) helps them grow.

Notwithstanding, when faced with a pressing situation, abstaining by avoiding making a decision is not always an option; therefore,

When in doubt, do it both ways.

iCritical reflection occurs when we analyze and challenge the validity of our presuppositions and assess the appropriateness of our knowledge, understanding, and beliefs given our present contexts.