Chapter 8

Developing and Sustaining Sponsorship

For many organizations, developing and sustaining sponsorship are difficult, nebulous tasks. The questions we often hear from champions of process improvement who are not part of the organization’s leadership include

• How do I get sponsors to provide the right resources (both type and amount) for our improvement effort?

• How do I help them set realistic goals?

• How do I help them change their behaviors to be more consistent with the goals we’ve agreed on?

• How do I sustain my sponsors’ interest in improvement, especially when results come slower than anticipated?

• How do I sustain sponsorship when the leadership of the organization changes? (This could be through merger, acquisition, personnel changes, and so on.)

For champions of process improvement who are already part of the organization’s leadership, some of the questions are easier to deal with. We’ll be focusing this section on champions who are trying to develop sponsorship and are not part of the organization’s formal leadership.

As you can see from the previous questions, much of the focus of developing and sustaining sponsorship involves goal setting, goal alignment, and communication. Especially where process improvement champions come primarily from an engineering background, these may be skills that have not been exercised very deeply up to this point.

8.1 Communicating with and Sustaining Sponsorship of Organizational leadership

It’s hard work to obtain effective sponsorship for your improvement effort. Equally important is sustaining that sponsorship. Each organization is different in terms of the exact mechanisms that will be needed to sustain your leadership’s involvement in and sponsorship of the improvement effort, but we’ve never run into an organization where communication wasn’t a key to those sustainment mechanisms.

What do sponsors want to hear about? In our experience, they mostly want assurance that (1) they’ve made the right decision to sponsor the improvement effort, (2) visible progress is being made toward the objectives that have been established for the improvement effort, and (3) The progress being made is consistent with the business goals of the organization.

CMMI has two Process Areas that specifically address these issues: Organizational Process Focus and Integrated Project Management. There is also at least one Generic Practice supporting the communication process that we’ll mention.

Organizational Process Focus’s goals are about the overall improvement effort: setting goals, appraising the state of the organization against those goals, and planning/implementing improvement actions in accordance with the organization’s current state and the goals. Consider the following appraisal practice:

SP 1.2 APPRAISE THE ORGANIZATION’s PROCESSES

Appraise the organization’s processes periodically and as needed to maintain an understanding of their strengths and weaknesses.1

1. Chrissis, Mary Beth, et al. CMMI: Guidelines for Process Integration and Product Improvement. 2d ed. (Boston: Addison-Wesley, 2006). All references to CMMI components in this chapter are from this source.

This practice is a key to providing sponsors confidence that their investment is on its way to reaping the benefits that led to the decision to invest. Surprisingly, this practice is not just about formal activities that result in auditable results, such as an ISO 9001 certification audit or a SCAMPI A appraisal. The main point of this practice is to encourage you to think about and implement ways to understand the progress of your improvement effort so that you can provide all the stakeholders—including the sponsors of the improvement effort—information on progress.

A more subtle interpretation of this practice involves evaluating the process improvement practices of the organization. Appraising the internal processes used for improvement is a good way to understand better how to conduct appraisal activities and also helps those working in process improvement understand the work they have to do on their own processes to meet their objectives.

Communication per se is covered in Integrated Project Management. Again, this is a goal-level issue:

SG 2 COORDINATE AND COLLABORATE WITH RELEVANT STAKEHOLDERS

Coordination and collaboration of the project with relevant stakeholders is conducted.

The “project” we’re talking about here is the improvement project. When we think about the relevant stakeholders we need to collaborate and communicate with, sponsors are pretty high, if not at the top of the list. So here’s a case where we can directly use practices within the project management category of CMMI to apply to our own process improvement “projects.”

There’s also a Generic Practice, one of the practices that can be applied to any Process Area of the model, that explicitly calls for communication with sponsors:

GP 2.10 REVIEW STATUS WITH HIGHER-LEVEL MANAGEMENT

Review the activities, status, and results of the PA process with higher level management and resolve issues.

This Generic Practice doesn’t define who “higher-level management” is in terms of exact roles. Instead, it encourages you to define which roles in your project/organization need to track status and then engage in review activities with them.

As you read the model, you will find other places that call for some specific communication about a particular topic.

8.2 Seeking Sponsors: Applying Sales Concepts to Building and Sustaining Support

One of the most interesting experiences SuZ had when working as the deployments manager for a small software company in the ‘90s was attending a “high-tech sales” seminar. This was one of those free, all-day awareness-building seminars meant to get you interested in taking a longer course. The topic of the seminar was Solution Selling, and the seminar was supported by a book of the same name.2 There she was with all those entrepreneurs and sales professionals, and after about the first hour, all SuZ could think about was how the concepts the instructor was talking about applied beautifully to process improvement. The concepts and techniques provided insights on why some of her most frustrating PI moments occurred. She started looking at sales techniques from the viewpoint of persuasion techniques: persuading sponsors to part with financial resources and political capital.

2. Bosworth, Michael, et al. Solution Selling: Creating Buyers in Difficult Selling Markets. (Scarborough, Ont.: Irwin Professional Publishing, 1995).

When you look at sales concepts and techniques as persuasion techniques, their fit in process improvement efforts becomes obvious. First, you have to persuade potential sponsors that it’s worth their time and effort to sanction the effort. Then you have to persuade key staff to participate in improvement activities. And then you have to persuade the group to actually adopt the new processes and practices that have been developed. That’s a lot of persuading going on! And if you’ve been educated as an engineer, you’ve most likely been taught that the primary tool for persuasion is your data set. The data set for engineering decisions is a good bit different from the data set for organizational improvement decisions. And often, the most persuasive data isn’t available until after improvement activities have taken place. So the alternative is a priori persuasion, which relies on analogy and anecdote.

Solution Selling techniques provide a nice series of understandable models to aid building and sustaining sponsorship. We’ll introduce a few of the concepts here but strongly suggest that you add the Solution Selling book to your reading list if you’re going to be one of the people trying to persuade your leadership to begin an improvement effort.

Key concepts from the Solution Selling seminar include

• Sales strategies are problem-solving strategies. The same kinds of issues that come up in facilitating a buyer’s acquiring a product come up in facilitating the introduction (“sale”) of a new technology into an organization.

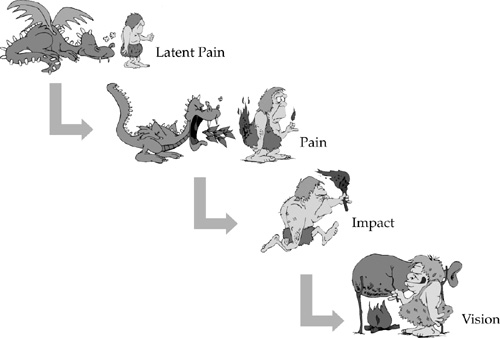

• Pain-Impact-Vision Cycle. The things you need to do to be successful in sales are similar to those you need to do in building sponsorship:

![]() Understand the buyer’s/sponsor’s need—the “pain” they are trying

Understand the buyer’s/sponsor’s need—the “pain” they are trying

to overcome.

![]() Help the buyer/sponsor move from a “feeling” of pain to an

Help the buyer/sponsor move from a “feeling” of pain to an

understanding of the business impacts of the pain.

![]() Help the buyer/sponsor create a vision of “what could be different”

Help the buyer/sponsor create a vision of “what could be different”

if the new practices were adopted.

• Buyer’s Risk Cycle. This cycle explains that understanding what’s important to buyers at different points in their buying cycle is very insightful when you’re looking at sponsorship decision cycle.

8.2.1 The Pain-Impact-Vision Cycle (PIV)

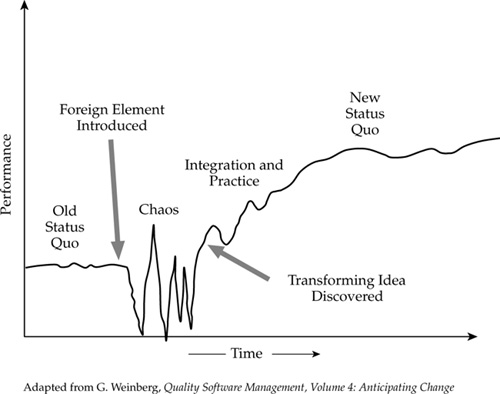

This cycle, shown in Figure 8-1, is what any buyer/sponsor navigates to get to a point where they can actually implement a complex solution. Solution Selling was invented to address the needs of high-tech sales professionals who are selling complex or advanced technical concepts to business-oriented decision makers. So the first step is to try to identify the “pain points” in the organization that relate to your solution and bring them to the forefront of the sponsor’s mind. At this stage, it is likely that those pain points are latent; they have become part of the background of the organization that is always there, and you really notice them only if the condition goes away. Those of you who have chronic back problems can relate easily to this. You don’t really realize how much pain you were in until you wake up one day (usually after medication and exercises and proper application of ice and heat…) and the pain is gone. What makes you decide to take the meds, do the exercises, and so on? For most of us, it’s the increase of pain beyond its chronic state into an acute state. Up until then, it’s just something we live with.

Figure 8-1: Solution Selling’s Pain-Impact-Vision Cycle

Solution Selling’s approach to moving a sponsor from latent pain to acute pain (pain uncomfortable enough to take action to change) is to focus on anxiety questions. These are usually open-ended questions that allow the sponsor to describe and elevate the awareness of areas of pain within the organization. So for identifying process improvement–related pain, you might use questions like “Tell me about your experiences with project completion in this organization” or “What is it like to manage projects when your organization goes through a hypergrowth spurt?” This allows them to talk about problems (and successes) and bring them to the forefront of their awareness.

When some areas of pain are identified, you help the sponsor understand the business impact of the pain areas. So here, you would ask capability questions, such as “How does not having enough people impact your ability to estimate projects accurately?” or “How much time do you think is lost in one-on-one training of new people in proper configuration management practices?” These questions are meant to connect some aspect of pain (shortage of resources, inefficient use of scarce resources) to a concrete business impact (cost and schedule overruns, quality). Especially at the beginning of an improvement cycle, this is a crucial aspect of getting buy-in, because you typically don’t have the kind of measurements going on within the organization that would allow the calculation of a “real” Return on Investment. If you have strong connections between pain areas and the business impact of the problems, solving them automatically provides a strong benefit to the organization. Clearly articulating these connections can act as a surrogate for ROI until you get more standard measures in place.

Moving a sponsor from business-impact realization to Vision involves connecting the solution (in this case, process improvement) to the Pain and the Impact. Often, this is done with control or confirming types of questions, such as “So you’re saying that if you had a way to include formal estimation in each project, you think your project performance would be better?” or “Would having a standard set of procedures for creating baselines help with your configuration management training problem?” Embedded in these questions is actually a piece of a solution.

The CMMI Business Analysis, covered in Chapter 12, is one technique for helping identify acute pain areas in relation to CMMI within an organization and understand their business impact. One of its purposes, by design, is to help move the organization through the PIV cycle.

Becoming familiar with this cycle and techniques to navigate it will help you get a potential sponsor’s attention and turn that attention into action. Interpreting the answers you get from the questions, however, can be more complicated than you might guess. This is because there are sets of conflicting issues that a buyer/sponsor is typically dealing with when going through this cycle. That’s where understanding the Buyer’s Risk Cycle comes into play.

8.2.2 The Buyer’s Risk Cycle

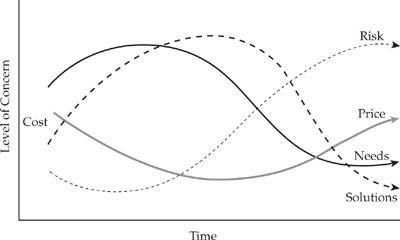

The four issues sponsors are juggling in their heads when provided a proposal for process improvement are

1. What are my needs related to process improvement?

2. How would this initiative fit my needs?

3. What is the cost/price of the initiative?

4. What are the risks if I say yes?

As Figure 8-2 illustrates, the amount of attention and concern that each of these elicits changes over time. Needs and cost issues are paramount to defining the sponsor’s pain and impact. As the sponsor moves toward Vision, the solution and price of the solution come into play, and at the very end of the cycle (when everything seems to be going swimmingly from your viewpoint as the champion), risk becomes the dominant issue. Understanding that this is a natural cycle will probably save you a few sleepless nights and help you understand the kind of information that’s needed, particularly at the end of the cycle.

Figure 8-2: Buyer’s Risk Cycle

SuZ relates the following story as an example:

When I was implementing process improvement in my home organization in the late 1980s, one of the practices I proposed was formal inspections—a technique that had tons of data behind it in terms of its ability to reduce the number of defects fielded in a complex system. It has some particular organizational needs, so I thought one of our more advanced projects would be most likely to succeed with it. I presented it to the project’s management, who liked the idea and had me present it to the technical staff. Up until the technical-staff presentation, everything looked like the project manager would approve.

At the presentation to the technical staff, there was a general reaction that “our projected defects are low enough at this point that we don’t see much benefit in a rigorous technique like this.” In other words, they weren’t feeling any pain (yet!). The project manager knew they were starting to slip schedules, but he didn’t see the connection between rework due to defects and schedule slips. So the negative tech-staff reaction raised the risk of reducing productivity by adopting a new technique. Two days later, he canceled the inspections initiative. His pain wasn’t acute enough to accept the risk of alienating his staff, who couldn’t even consider any pain. So I went to another project that was not nearly as “advanced” but had a tremendous number of defects. Their schedule couldn’t tolerate the rework from the defect injection level they were experiencing. Their pain was acute, and its business impact was clear to both the team and management. Formal inspections were a visibly perfect match to their situation.

Not surprisingly, after the first delivery on the “advanced” project, their technical lead came to me asking if I could teach them formal inspections; their delivered defects versus projected defects were not even close, and they were experiencing the pain of customer complaints in a big way. Their latent pain had indeed become acute!

8.3 Being a Sponsor: Welcome to the “Foreign Element”

So you’re in a position of leadership within an organization, and you’ve decided to think about adopting some model for process improvement. You’ve probably made changes happen in your organization before, but you may not have thought about what was happening in your organization while the change was taking place. We’ve found that understanding some of the dynamics of how people react to change (after all, it’s people we’re asking to change their behavior) is helpful both to sponsors and to those asked to change.

There are several ways of representing the cycle of responses human beings make to change. The most useful one that we have found is called the Satir Change Model, after its author, Virginia Satir. It is useful both because it is descriptive (it does a pretty decent job of explaining the symptoms that we often see in organizations going through a change) and because it is somewhat prescriptive (it provides some ideas of what you can do to make it easier for people to navigate the cycle of change). Our interpretation of the Satir model relies most heavily on Gerald Weinberg’s explanation of it in his book Quality Software Management Volume 4: Anticipating Change. 3

3. Weinberg, Gerald. Quality Software Management Volume 4: Anticipating Change. (New York: Dorset House Publishing, 1997).

Figure 8-3 presents a graphic summary of the Satir Change Model. The individual or group starts out at some level of performance, represented as the Old Status Quo. The introduction of a change intended to improve the individual or group’s performance is treated by the group as a “foreign element.” The group will have different reactions to the foreign element. Some of the possibilities include

• Trying to ignore the foreign element

• Trying to find a way to accommodate the foreign element within their own current way of doing things

• Trying to explicitly reject the foreign element

The energy that goes into these reactions causes swings in the performance of the group that can be dramatic, depending on the character and size of the change being introduced. At some point, if the foreign element doesn’t go away, most groups will find what Satir calls the “transforming idea” that will allow the group to integrate the change into their way of doing things and will allow them to move on. When the group has found and accepted a transforming idea, it proceeds to integrate the new behavior into its routines by practicing the new behavior. During this time, the group’s performance starts to improve; however, this increased performance can occur only if there is opportunity for practice of the new behavior. After the new behavior is integrated into the group’s behavior, it becomes the new status quo, and whatever performance increases have been achieved are likely to continue at this point.

We’ll discuss particular aspects and implications of the Satir Change Model at various points in our journey. One of the most important aspects of the Satir model in relation to building and sustaining sponsorship is to recognize that the timing of the cycle is different for different individuals and groups within the organization. In particular, what often happens in an organization is that the members of the leadership group get exposed to a foreign element, go through their own phase of chaos, figure out the transforming idea and integrate it into their own thinking, and then are ready to have the organization adopt it. When you, as the sponsor of the change, propose it or announce it to your subordinates, you’ve gone through your change cycle, but they haven’t yet, so what you’re introducing to them is their foreign element. They still have their own change cycle to go through. This lack of synchronization between the change cycles of different groups within an organization (one group has already integrated the change, another is in the middle of trying to find its transforming idea, and still another hasn’t even seen the foreign element yet) is one of the greatest challenges for sponsors, especially when the sponsor has already completed the change cycle and has a vision of how he or she wants the organization’s performance to be enhanced.

Figure 8-3: Graphical summary of the Satir Change Model