How Exposure Is Calculated

Now that we know about the three core elements of exposure—ISO, shutter speed, and aperture—let’s take a closer look at how they relate to one another and how you can change them as needed.

When you point your camera at a scene, the light reflecting off your subject enters the lens and is allowed to pass through to your sensor for a period of time. The amount and duration of the light needed for a proper exposure depends on how much light is being reflected and how sensitive the sensor is (ISO). In order to determine the amount of light in a given scene, your camera utilizes a built-in light meter that reads the light coming through the lens. The amount of light is then calculated against the sensitivity of the sensor (ISO), and an exposure level is rendered. The challenging aspect of understanding exposure is that there is no one way to achieve a well-exposed image. The combinations of ISO, shutter speed, and aperture are endless. The fun, creative part is in choosing which exposure (the mix of ISO, shutter speed, and aperture) you want for a given image.

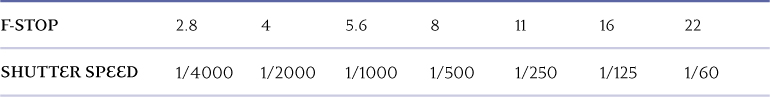

Here is a list of reciprocal settings that would all produce the same exposure result. Let’s use the “sunny 16” rule, which states that, when using f/16 on a sunny day, you can use a shutter speed that is roughly equal to your ISO setting to achieve a proper exposure. For simplification purposes, we will use an ISO of 100.

Reciprocal Exposures: ISO 100

Each of these combinations would have the same result in terms of the exposure (that is, how much light hits the camera’s sensor). Also take note that every time we cut the f-stop in half, we reciprocated by doubling our shutter speed. For those of you wondering why f/5.6 is half of f/8, it’s because those numbers are actually fractions based on the opening of the lens in relation to its focal length. This means that a lot of math goes into figuring out just what the total area of a lens opening is, so you just have to take it on faith that f/5.6 is half of f/8 but twice as much as f/4. A good way to remember which opening is larger is to think of your camera lens as a pipe that controls the flow of water. If you had a pipe that was 1/2” in diameter (f/2) and one that was 1/8” (f/8), which would allow more water to flow through? It would be the 1/2” pipe. The same idea works here with the camera f-stops; f/2 is a larger opening than f/4 or f/8 or f/16.

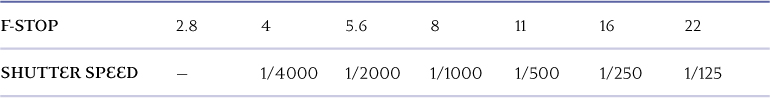

Now that we know this, we can start using this information to make intelligent choices in terms of shutter speed and f-stop. Let’s bring the third element into this by changing our ISO by one stop, from 100 to 200.

Reciprocal Exposures: ISO 200

Notice that since we doubled the sensitivity of the sensor, we now require half as much exposure as before. We have also reduced our maximum aperture from f/2 to f/4, because the camera can’t use a shutter speed that is faster than 1/4000 of a second.

So why not just use the exposure setting of f/16 at 1/250 of a second? Why bother with all of these reciprocal values when this one setting will give us a properly exposed image? The answer is that the f-stop and shutter speed also control two other important aspects of our image: motion and depth of field.