CHAPTER 2

The Importance of Culture, Climate, and Tribes in the Context of Enterprise Architecture

In this chapter, we consider the influences of culture and the related concepts of tribes and organizational climate on enterprise architecture (EA). As described in Chapter 1, the essence of EA involves planning and transformation of enterprises. However, no matter how carefully we plan for change and account for the nature of the systems we are concerned with, we face emergent and unexpected consequences resulting from human factors. Such factors can, however, be understood based on the culture of the enterprise and the metacultures (occupational, regional, national, and beyond) in which it is situated.

Cultures are like nested dolls or layers of an onion: as we peel or open one culture, we find that others are nested within, and each of those layers concomitantly provide a wider universe in which they are embedded. This is the dilemma: How do we characterize the culture of the enterprise or the portions of the culture that impact the transformation projects we propose? This chapter discusses approaches to culture and proposes how they can be modeled and incorporated into a project for the purposes of creating EA. It examines various ways of viewing, characterizing, and analyzing culture and documenting it within an architecture. Culture is an important concept, because it influences the attitudes and behaviors of members of organizations and enterprises and thus impacts their reactions to attempts at organizational or enterprise transformation.

Introduction to Culture

It is a common assertion that although all humans have culture, it is something we learn, and in the case of national and ethnic cultures, it is passed down between generations. In addition to such macro notions of culture, we recognize its relevance to virtually all forms of human collectivity, including those we identify as enterprises and organizations.

Origins of Culture Study

The formal study of culture emerged from the disciplines of anthropology and sociology during the colonial period of European and American political expansions over different populations with intent to administer and control them better. This introduced a variety of functionalist and structural theories for understanding different types of organization, from highly controlled hierarchical bodies, to self-adapting structures such as African segmentary lineage, or tribal, systems. These systems can be described as “tribes without rulers,” where lineages have formed into larger entities based on need and circumstances to manage some external risk. They are sometimes called “ordered anarchies.”

In the late 1970s, the concept of culture was first introduced to the study of formal organizations [Pettigrew 1979]. This led to ethnographic studies of organizations, such as Edgar Schein on the Digital Equipment Corporation (2004), Gideon Kunda (2006) on engineering culture, Michael Lynch (1985) on laboratory culture, and Eric Livingston (2016) on mathematical reasoning. Concomitant with qualitative based organizational culture studies, particularly within the management and organizational behavior disciplines, a more quantitative approach focused on attitudes and behaviors across organizations, forming the basis for studies in organizational climate.

Organizational Climate and Organizational Culture

In the introduction to their handbook of organizational climate and culture studies, Schneider and Barbera (2014) provided the following working definition for organizational climate: “the meaning organizational employees attach to the policies, practices, and procedures they experience and the behaviors they observe getting rewarded, supported and expected.” This is contrasted with organizational culture: “the values and beliefs that characterize organizations, as transmitted by the socialization experiences newcomers have, the decisions made by management, and the stories and myths people tell and re-tell about their organizations.” These definitions suggest that climate is at a conscious and behavioral level and is more easily changed than the underlying value and belief structures of culture that underlie such behavior. According to Schein, organizational climate can be considered a visible artifact of the underlying taken-for-granted assumption system constituting the basis of culture.

Corporate Tribes

In addition to culture and climate is the concept of corporate tribes. Joanne Martin (2002) describes organizational cultures as being simultaneously integrated, differentiated, and fragmented. A tribe can be considered a differentiated part of a larger cultural manifestation that maintains its own identity and political foundation [Wilcock 2004]. As with the anthropological characterization, a corporate culture can be organized into a number of clans or tribes. These share common cultural assumptions but are corporate entities that often compete with one another. In organizational contexts, tribes are usually groups of between 20 and 150 people. When networks scale, they produce phase transitions common to all organisms, cities, economies, or companies.

As described in Malcom Gladwell’s The Tipping Point (2000), tribes adapt and shift in how they exercise power. For the purposes of this book, we consider tribes to be politicized cohorts (that is, groups) that can either facilitate or impede organizational initiatives. Tribes can function either formally or informally as communities of practice, and they can also function across organizational boundaries. An example of tribal influence can be seen in the analysis of the over $1.1 billion failure of an ERP (Enterprise Resource Planning) Oracle implementation: the Expeditionary Combat Support System (ECSS) for the Air Force. The Government Accountability Office and Congress eventually determined that the most significant issues underlying that failure were cultural. This finding is particularly telling, because defense organizations, such as the Air Force, have a highly organized command and control hierarchy, yet efforts to implement ECSS were impeded by a highly fragmented and diversified organizational cultural reality. Tribal cohorts led resistance to change and negatively impacted the success of the project. In this book, we consider how culture, tribes, and organizational climate differences impact enterprise architecture, and we suggest approaches for their effective management.

Chapter 3, in the case study of an airport, introduces a variety of architecture viewpoints. These viewpoints are representative of differentiated subcultures or tribal perspectives including air operations, cargo, security, TSA, and air traffic management. As of this writing, the administration has advanced the privatization of air traffic control as the first major infrastructure proposal. We can anticipate cultural response and forms of resistance from NATCA (National Air Traffic Control Association). In 2006, the FAA imposed drastic cuts in their contract with NATCA, resulting in lower salaries for new employees and changes in working conditions. This led to a significant staffing crisis, increases in runway incursions, and an increase in delays. A shift toward privatization has both supporters and detractors within the union, and depending on location, the implementation of such a plan must address the cultural acceptance of such a transformation.

Likewise, an airport’s decision of whether to use TSA or outsource security screening to security contractors proffers both advantages and challenges to FAA employees, who form a cohort that can coalesce into tribal resistance to change. Such challenges can present themselves as opportunities if the cultural assumptions of the tribal entities are understood and incorporated into EA planning and structure. The natures of such underlying assumption systems are discussed in this chapter.

Understanding Culture: Language Perspective

Culture is like language (and is expressed within it), in that every human society has language, and its possession as a symbolic mode of representation is one of the distinguishing features of being human. Like language, cultural structure functions at an underlying level and is, as organizational culture theorist Geert Hofstede included in a title of one of his books, the “software of the mind.” As he explains, culture involves unwritten rules of a social game, and “is the collective programming of the mind that distinguishes the members of one group or category of people from another.” [Hofstede 2010] This “collective programming” obtains at every level of culture. One way of understanding culture is as a system, and systems science recognizes that systems exist within systems. We must identify the boundaries of the cultural system that interests us in our architectural analysis.

If we understand a system as being composed of two or more subsystems oriented toward a common purpose, we can situate cultures within cultures within cultures. In this manner, we can argue that there is an organizational culture to continuous larger groupings, the largest of which would be human culture. Understanding the underlying systems constituting human culture or human nature was a primary motivation of structuralists such as Levi-Strauss, who deconstructed cross-cultural symbol systems of myth, ritual, art, and other processes looking for underlying and universal patterns.

We can distinguish between those whose interests are to peel back the layers of culture to locate invariant properties, and those who focus on what distinguishes groups from one another. For our purposes, we are concerned with cultural differences and how they affect organizational behavior.

Although we recognize differences in organizational culture, they are most often attributed to negative experiences, such as encounters with not-invented-here attitudes and turf battles between and among functional stovepipe organizations. So initiatives such as EA may be challenged as unwelcome intrusions by management to put another bureaucratic obstacle in the way of those who do the real work. From this point of view, culture can be seen as an impediment and something that has to be managed, dealt with, and changed. As Hofstede observed, “Culture is more often a source of conflict than of synergy. Cultural differences are a nuisance at best and often a disaster.”

Yet culture, like language, is neutral. It is not defined in terms of content; rather it exists at the underlying deep structural level that gives rise to surface behavior. Consider the parallels of language and culture. Every language has an underlying structure of an essentially finite number of rules that give rise to a virtually infinite number of possible expressions in the language. The underlying rule system is often referred to as “deep structure,” and the way the application of the rules appears in discourse is called “surface structure.” These underlying systems are not always apparent to speakers and need to be discovered in linguistic analysis.

There is no language superior to another in being able to express information. In this manner, languages represent metaphoric parallel universes. Culture, likewise, can be understood according to an underlying system of rule-like structures. One way of considering culture is to characterize it as a form of social cognition. Ray Jackendoff (2007) provides an important comparison between language and social cognition, showing how both comprise underlying rule patterns that are not directly available to consciousness. In his book Language, Consciousness, Culture he provides a table, illustrated in Figure 2-1, to show these relationships.

Figure 2-1 Parallels between language and social cognition (used with permission from MIT Press)

Both language and culture (characterized as a type of social cognition or thought process) have finite underlying structures or combinational rule systems that generate a virtually infinite number of displays: sentences and understandable social situations that are at the surface or surface structures. Although these underlying systematic structures generate meaning, the latter is independent of them. We can communicate any number and kind of messages with language, as we can perform any number and kind of culturally relevant behavior. In this manner, we reserve judgment on cultural performance in the same way that we do on what might be said.

Using language, we can complement or insult, make promises, offers, or threats using the similar language principles. As anthropologist Dell Hymes (1977) showed, culture is a “system of ideas that underlies and gives meaning to behavior in society, and what is distinctively cultural is a question of capabilities acquired or elicited in social life rather than the behavior or things that are shared.” This allows for the same underlying system of rules to elicit outcomes that are in conflict with one another. This potential for conflict was the basis for Schein’s observation regarding the culture at the Digital Equipment Corporation, which entailed both “a positive innovative culture that could at the same time grind out ‘fabulous new products’ and develop such strong internal animosities that groups would accuse one another of lying, cheating and misuse of resources.” According to Schein (2004), the underlying cultural grammar at DEC was responsible for both its meteoric rise to success and its eventual downfall.

Classifying Cultures

Although we characterize deep structure as a finite set of rules that generates a virtually infinite variety of surface structures (sentences in language and social situations in culture), these rules are highly complex. They are self-adaptive, nonlinear, and complex. For culture, there are invariant structures contained in its universal presence in all human societies, and variant structures that enable us to classify cultures according to various value and other dimensions. The comparison and measuring of differences in cultural value orientation is a significant advance in the study of intercultural communications. Approaches to this type of classification give us a way of understanding the corporate culture and subcultures of the enterprise we are dealing with and a way of predicting at least some of the conflicts that will arise.

Power Distance Index

Hofstede developed a framework for this in his comparative study of IBM in different countries to locate what dimensions differ in behavior, by observing and interviewing persons at the same level in the corporate hierarchy around the world. He developed a value dimensions comparison: power distance, uncertainty avoidance, individualism/collectivism, and masculinity/femininity.

His Power Distance Index (PDI) focuses on the degree of equality, or inequality, between people in society. High power distance indicates that inequalities of power and wealth exist and are tolerated within the society. Such societies often have caste systems that do not allow upward mobility. In low power distance societies, there is a de-emphasis on structural differentiation, and equality along with opportunity for everyone is emphasized. Hofstede measured power distance according to how those he interviewed responded to such questions as, “how frequently does the following occur: employees being afraid to express disagreement with managers,” and subordinates’ perception and then preference for a boss’s decision-making style, choosing between autocratic, paternalistic, or consultative.

Hofstede’s distinction between individualism and collectivism focuses on how much a society emphasizes individual versus collective achievement and interpersonal relationships. High individualism stresses individuality and individual rights, and individuals tend toward looser relationships. Low individualism societies emphasize collectivist natures and closer ties between individuals. In such cultures, extended families are emphasized and everyone assumes responsibility for fellow group members. Hofstede contrasts locus of control and evaluation between these types. If this focus is external to the individual, as is found in more collectivistic societies, there is a greater emphasis on fatalism and lack of individual responsibility, whereas an internal focus tends to emphasize a rejection of submission to authority.

In Hofstede’s interviews, he determined the contrast of individualism versus collectivism according to how his respondents answered several questions. Answers that included a desire for personal time, freedom to adopt an individual approach to a job, and challenging work indicate an orientation toward individualistic. On the other hand, answers that emphasized a desire for training, physical conditions, and use of one’s skills tended toward the collectivistic.

Hofstede’s Masculinity (MAS) ranking focuses on how much a society reinforces traditional masculine work role models of achievement, control, and power. High MAS indicates the cultural experiences in gender differentiation, where males maintain a hegemonic role in the power structure. In low masculinity cultures, there is less discrimination between genders and women are treated with greater equality. Hofstede contrasted Masculine versus Feminine cultures according to how respondents ranked a series of preferences regarding work environments. Masculine emphasizes earnings, recognition, advancement, and work challenges; Feminine emphasizes having good working relationships with managers, cooperation with co-workers, living in a desirable area, and employment security.

His next area of contrast was the level of uncertainty avoidance (UAI). UAI focuses on the amount of tolerance for ambiguity and uncertainty or unstructured situations. High uncertainty avoidance rankings that show a low tolerance for uncertainty and ambiguity create a rule-oriented society that stresses laws, rules, regulations, and controls to reduce the amount of uncertainty. A low ranking indicates less concern about ambiguity and more tolerance for differences of opinion. Low uncertainty avoidance societies are less rule oriented, more acceptable of change, and readier to take risks.

Hofstede’s final contrast involved time orientation—high long term (LTO) versus low. This measure looked at the amount of focus on traditional versus forward-thinking values. High LTO shows a commitment and respect for tradition with a strong work ethic, where long-term rewards are anticipated for today’s work. In such societies, business often takes longer to develop for outsiders.

One of the authors found a curious example of this several years ago when he learned about a benefit that Canon Business Machines, a Japanese firm, wanted to make to its American managers at a facility in the United States. They offered to pay for the tuition of all of their managers’ children in college so that the cost of education would not be a barrier to entry into any university. Interestingly, the American managers almost universally rebelled against the offer, saying they would prefer receiving the compensation now and they would take care of their children’s education. This offer was made during a period when Japanese industry expected workers to remain loyal to their company throughout their career. This contrasted to American business experience, where advancing in one’s career more often involved lateral moves to other companies, and lifelong loyalty to an organization was rare.

Hofstede, and those making similar contrasts between cultures, hypothesized the ability to predict types of interactive styles between those expressing such value orientation differences, such as exemplified in the case of Canon Business Machines just cited. Where Hofstede emphasized intercultural distinctions between national cultures, different organizations, and professions also differ in their expression of these differences. For instance, one might contrast the academic profession and government service that provide tenure and more job security with the uncertainty, short-term project orientation, and individual advancement stressed in contract-based consulting professions and in highly competitive industries. Consider how Dan Bricklin and Bob Frankston, the inventors of the first killer application (VisiCalc), as university professors, published the source code as standard for the academic profession. Their reward was tenure and a well-deserved reputation, but they did not become computer billionaires like Bill Gates, Steve Jobs, or Larry Ellison.

Grid and Group

Contrasts of macro-national cultural differences with micro-organizational distinctions are also strongly exemplified in anthropologist Mary Douglas’s distinction between grid and group. Douglas first discussed this contrast in her book Natural Symbols (1970), based on research in Central Africa. Douglas was concerned with how people ordered their universe and proposed a system of classification for how they went about doing so. She developed a typology to account for the distribution of values within society. She proposed a connection between kinds of social organization and the values that maintain them.

Douglas developed a schema based on two dimensions: ground (referring to a general boundary around a community) that forms the basis of a horizontal axis, and grid (or regulation) on the vertical axis. Members of a society or an organization move across the matrix according to choice or to circumstances. Douglas’s grid/group diagram appears as Figure 2-2.

Figure 2-2 Matrix with associated ideal types of personas

The ground, or group, dimension is a measure of how much people are controlled by their social group. Individuals need to accept constraints on behavior when they are affiliated with a group. Groups require collective pressures to demonstrate loyalty. Douglas points out that these constraints obviously vary in strength. She gives the example of how at one end of the spectrum an individual might belong to a religious group and attend services only on major holy days, while at the other end of the spectrum are those who join convents and monasteries.

The other variable on the grid is the differences in amount of control or structure members of a group accept. On one hand, individuals live free of group pressures and structural constraints, where everything “has to be negotiated ad hoc”; on the other hand, others live in highly structured hierarchical environments. The grid creates four opposed and incompatible types of social control, with various mixtures between the extremes.

Douglas provides a characterization of three ideal types of persona associated with the grid (see Figure 2-2). She describes these as “The smug pioneer with his pickaxe, the stern bureaucrat with his briefcase, the holy man with his halo,” each exemplifying German sociologist Max Weber’s types of rationality: bureaucracy, market, and religious charisma. These reflect the three grid-group cultures of positional, individualist, and sectarian enclave.

She describes how the positional society at the top right is strong on grid and group. This reflects societies and concomitantly organizations in which all roles are ascribed and behavior is governed by positional rules. The cultural biases are tradition and order. In culture, the roles are ascribed by birth, gender, or family and ranked according to tradition. She refers to this as “positional,” as a form of society that uses “extensive classification and programming for solving problems of co-ordination.” In the organizational domain, the positional enterprise might be the family owned and controlled business where employees can expect to achieve only a certain level of power within the enterprise.

At the lower right-hand (enclave) position are strongly bounded groups with little or no ranking or grading rules for the relationships among its members. Douglas considers this to be descriptive of a community of dissidents or sects. This might also pertain to lattice design organizations [Papa et al. 2008], where there are no bosses. New members are not assigned to departments but find teams that they volunteer to join. The lattice organization encourages direct communication with few intermediaries or little approval seeking. Instead of a defined authority structure, team members commit to objectives to make them happen. Lattice organizations have sponsors rather than bosses. According to Papa, such organizations involve a heterarchy, with self-organizing, non-hierarchical systems characterized by lateral accountability and by organizational heterogeneity. Lattice organizations involve distributed intelligence and diversity. They comprise multiple communities of knowledge and practice with diverse evaluative and performance criteria and answer to different constituencies and principles of accountability.

At the lower left is extreme individualism. This type of society or organizations is defined in terms of both weak group and grid controls. The primary form of control is competition. Dominant positions are open to merit. Douglas sees this as a commercial society, where the individual is concerned only with private benefit. This type of society also exhibits a “greed is good” mentality and the extremism that led to the collapse of banking in the recent recession.

The fourth quadrant (upper right) is the world of the total isolate, and it is populated by those who withdraw from society. As an organizational form, this might be the independent researcher and entrepreneur.

Douglas later described the grid as the basis for understanding how organizations think. This approach reflected an alternative view of corporate culture. In such a schema, we may be tempted toward a Goethe type of prediction regarding interactions between the systems in these quadrants. However, rather than being predictive, we may instead consider characterizations to be elements of cultural grammars that can yield any number of types of surface structures. Thus, as Douglas argued, culture is not a thing; it is not static but instead is “something which everyone is constantly creating, affirming and expressing.” From this perspective, culture is not imposed but rather emerges. Organizational culture is the result of continuing negotiations regarding values, meanings, and proprieties among members of an organization and within its environment. Culture is the consequence of interactions and negotiations among members of organizations. To change culture may require that we change the nature of those conversations. This type of change is not trivial.

As Harold Garfinkel (1967) argued for health clinical records, there are “good organizational reasons” for bad organizational behavior. That is, at the macro level, we can easily see “organizational problems,” but as we move to what he refers to as the “shop floor,” we tend to “lose the phenomenon.” Thus, when we try to investigate some macro organizational problem, we often find good rationales for what is being done at the local level. That is, asking “why do you do things in that way?” yields responses that make good sense in the situation and setting where the work actually gets done.

How Culture Affects the Enterprise Architecture

Organizational psychologist Karl Weick describes how every organization, including the most effective ones, are essentially “garrulous, clumsy, superstitious, hypocritical, monstrous, octopoid, wandering and grouchy” (1977). This is because organizations organically emerge out of the communication patterns that develop in the course of doing business and in response to the host of environmental variables in dynamically changing business landscapes. Enterprises are instances of complex adaptive systems having many interacting subcomponents whose interactions yield complex behaviors. Complexity involves a “duality of interactive complex systems,” in which “duality” refers to the idea that every action produces a ripple effect, on interdependent actors—that is, the “structure.” This ripple effect, in turn, shapes “actions.”

Enterprises are by their very nature disorganized. Russ Ackoff argued that all organizations are a mess. It is the architect’s job to support the transformation of the organization by rolling up our sleeves and defining the mess and proposing solutions. Ackoff described the nature of the problem of messes that faces us:

In a real sense, problems do not exist. They are distractions from real situations. The real situations from which they are abstracted are messes. A mess is a system of interrelated problems. We should be concerned with messes, not problems. The solution to a mess is not equal to the sum of the solution to its parts. The solution to its parts should be derived from the solution of the whole; not vice versa. Science has provided powerful methods, techniques and tools for solving problems, but it has provided little that can help in solving messes. The lack of mess-solving capability is the most important challenge facing us. [Ackoff 1994, pp 210–12]

Ackoff advocates five steps for solving these messes: formulating the mess, ends planning, means planning, resource planning, and the design of implementation and control systems. In one way or other, most business process renewal or reengineering efforts involve some version of this approach.

The first step is to formulate the mess: “A corporation’s mess is the future implied by it and its environment’s current behavior. Every system contains the seeds of its own deterioration and destruction. Therefore, the purpose of formulating the mess is to identify the nature of these often-concealed threats and to suggest changes that can increase the corporation’s ability to survive and thrive.” Figuring out that mess involves three types of work. The first is an analysis of the state of the organization (or corporation) and how it interacts with the environment. Next is an “obstruction analysis” to identify the obstructions to development. Then we prepare reference projections engaging in the four stages leading to the transformation.

These tasks are often easier said than done. Consider most instances when we decide to clean up some mess, such as spring cleaning or cleaning up our offices after the conclusion of a major project. When I do so, I normally get a number of big black garbage or lawn bags with the intent to toss away what I no longer need. However, by the end of the day, I am always taken back by the small amount of trash I actually have. It seems that with each file or paper I pick up, I find “strange connections” to other files and projects that are ongoing or have perceived potential to next projects I will be involved with. So I end up throwing away perhaps copies of documents and a few other non-relevant materials, but for the most part I just refile or sort what I already have.

This description of the “mess” fits what we have recently learned about the nature of chaotic systems. In spite of perceived disorganized chaos, there seems to be what John Holland (1996) calls a “hidden order” to things. Rather than systems being totally random and chaotic, they are better understood as highly complex and self-adapting. In such systems, components become associated with one another by what complexity theorists call “strange attractors,” which lead to new patterns entailing the emergence of new organizational forms.

There is a distinction between complication and emergence. In the latter, we may understand what components make up some situation or event. However, in such systems there are often interconnections between components that are almost impossible to take into account. Consider, for instance, the phenomenon of weather. Although understanding the dynamics of weather and the range of variable involved, we are, despite the literally billions spent on predictive technologies, unable to fully predict it. This leads to the concept of what has become known as the “butterfly effect,” which was originally conceived by MIT meteorologist Edward Lorenz, who created a mathematical model of the weather. He suggested how minute changes, as minimal as the flap of the wing of a butterfly, could have impacts on other molecules that are forming together to create weather patterns. That is, the wing flap is associated with other molecules through strange attraction and lead to unexpected events. His model led him to realize that long-term forecasting was doomed to failure. The butterfly effect suggests that a butterfly flapping its wings can affect the world’s weather, and upon the suggestion of another colleague, Lorenz titled a paper he presented to the AAAS in 1972 “Does the flap of a butterfly’s wings in Brazil set off a tornado in Texas?” that emphasized such interaction [Lorenz 1993].

We are, however, not condemned to incomprehensible complexity. We can, after all, make approximate predictions of weather along with a wide range of natural, cultural, and organizational behavior. We may not be precise, but we can approximate a “for-all-practical-purposes” mode of description. In a very real sense, that is what we intend in modeling the complexity of an enterprise. We can establish relationships between operational, systems, and technical nodes in a highly complex organization that enables us to plan for organizational transformation. Such modeling is far superior to no planning at all. This again brings up Ackoff’s point about plan or be planned for. It is important to be proactive and enact the organizational changes we want rather than be reactive to events as they chaotically unfurl.

Social Networks

Weick’s portrayal of organizations as wandering and octopoid characterizes how we encounter them. Despite such ubiquitous chaos, we seem to find order. However, order is something we do to organizations rather than it being an inherent property of them. We create order through our beliefs about organizations. These beliefs constitute “cause maps” that we impose on the world and, once imposed, characterize our view of organizations.

This imposition of order is also known as the “process of structuration” [Giddens 1986]. Repeated interactions are the foundation of social structure. Interacting individuals whose activities are in turn constrained by that perceived constructed structure produce structure. This Giddens calls the “duality of structure.” This duality describes how social structures constrain choices and at the same time how social structures are created by the activities they constrain.

Structure does not exist in its own right. Rather, it is through enactments that we produce organization as ongoing accomplishments and reify their structure. The kind of sense that an organization makes of its thoughts and of itself has an effect on its ability to deal with change. An organization that continually sees itself in novel images that are permeated with diverse skills and sensitivities is equipped to deal with altered surroundings when they appear. Weick argues that organizational transformation continually involves enactment. Enactment is a form of social construction in social networks.

Connectedness in an organization characterizes the social networks within the organization. The study of social networks has led to a field within organizational and communications studies known as social network theory, which analyzes social relationships according to nodes and types that define them. There are three types of nodes:

• Operational nodes are the individual actors in networks that have ties that characterize the resources/information that they exchange.

• Systems nodes are the structures or systems individuals use in their communication.

• Technical nodes are the technical components of those systems.

In enterprise architecture, each of these types of nodes can be represented in different views that document the types of ties and information flows that occur between them.

The study of social networks in organizations or organizational network analysis offers an approach to understand the internal workings of an organization. Organization charts prescribe how work and information flow in a hierarchy, but network mapping reveals that they actually flow through a web of informal channels. These informal channels point to significant differences between the formal organizational structural view and what is actually occurring in the daily life of the enterprise. These differences have important impacts on how work gets done, and knowledge of the informal channels enables analysis of bottlenecks, inefficiencies, and gaps in business processes. The organization’s enterprise architecture captures and documents these informal channels and information flows to enable this analysis of business processes.

An important discovery in the study of social networks is the importance of applying graph theory to understand the complexity involved. Graph theory is the substance of contemporary network analysis, and it formulates the basis for the range of network type diagrams used in different enterprise architectural products. Social network theorist Rob Cross describes ONA (Organizational Network Analysis) as “a powerful means of making invisible patterns of information flow and collaboration in strategically important groups visible.” Cross and his colleagues interviewed members of organizations to uncover the types of links that existed between them and graphed these relationships, connecting the members as nodes. This often led to some quite surprising results. In every social network, different people played different roles, ranging from central, peripheral, boundary spanner, and isolates. Architects do the same and document using the views of the framework they are using.

There is no single network structure or role positioning that is best for all organizations. For instance, in some organizations, a few individuals may be in a highly interactive role connecting different subgroups together. In a close examination of what is occurring, sometimes we find that these individuals function more as bottlenecks than enablers. Once their functions within the organization are shared with other positions, information and workflow is made more efficient. However, in some instances, such boundary spanning positions are relevant, allowing close management of projects.

What is important in network analysis is to uncover whether the structure is intentional and functional, or whether the networks are emergent structures that impede the work and communication flows within the enterprise. Cross, Liedtka, and Weiss (2005) characterized three types of organizational networks: customized response networks, modularized response networks, and routine response networks. Each represents a different value proposition that affects the patterns of collaboration that occur. The authors propose that managers should not force collaboration onto all employees and must take into account the appropriate proposition and organizational mission.

Customized response networks exist in organizational contexts where there is ambiguity in both problems and solutions. Examples could include new product-development companies, high-end investment financial institutions, early-stage drug development teams, and strategy consulting firms. They require networks that allow rapid definition of problems and coordination of expertise in response. The quick framing and problem solving in an innovative manner derive value.

Modular response networks exist in contexts where parts of a problem and solution are known, but the sequencing of these components is not known. Cross and his colleagues give as examples surgical teams, business-to-business sales, and mid-stage drug development teams. These types of organizations have networks to identify problem elements and to deal with them using modularized expertise. Value comes from delivering a unique response based on types of expertise required by particular problems such as a lawsuit or surgical procedure.

Routine response networks are found in standardized work contexts. Here problems and solutions are well defined and predictable. This includes call centers, claims processing, and late-stage drug development. Value is derived by efficient and consistent response to established problems.

Each of these three network types requires different types of communication flows. In highly innovative and creative contexts, it is important for those directly involved to be in close, frequent communication where expertise is redundant, as well as having boundary spanning access to other networks dealing with related issues. However, it is also important for some experts, such as scientists, to have independence and not always be closely managed such that their creativity is impeded. In the modular response networks, there is more interchangeability of roles and more structured approach to boundary spanning. In routine response networks, there are defined and structured boundaries with clear lines of authority and role relationships. Figure 2-3 shows the parameters for each network type [Cross et al. 2006].

Figure 2-3 Social networks (used with permission from Harvard University Press)

As discussed, some see culture as very inclusive and define it in ways in which it is hard to conceive of what might be outside the boundaries of culture: “Culture is the deposit of knowledge, experiences, beliefs, values, attitudes, meanings, hierarchies, religion, timing, roles, spatial relations, concepts of the universe (world view), and material objects and possessions acquired by a group of people in the course of generations through individual and group striving.” [Gudykunst and Kim 2002] Anthropological and sociological ethnographers spend years doing ethnographic fieldwork to write up their studies of culture. As enterprise architects, we surely cannot undertake such an effort.

So, the bad news is that a full ethnographic account of culture can take a significant investment of time and effort. The good news is that a full, comprehensive analysis of culture is not required to understand the cultural features that we require in enterprise architecture. Schein (2010) suggests a clinical ethnographic approach. Rather than being concerned with researching the complexity of organizational culture, a clinical perspective entails an action research perspective. Here, the goal is to undertake cultural analysis to uncover the basic systemic cultural assumptions that give rise to particular problems, issues, and concerns within an organization. For example, Schein used this approach in analyzing the DEC culture, locating those cultural principles or assumptions that led both to its meteoric success and to its eventual decline. He argues we need to understand culture as the “pattern of shared basic assumptions that the group learned as it solved its problems of external adaptation and internal integration that has worked well enough to be considered valid and … to be taught to new members as the correct way to perceive, think and feel in relation to those problems.” (2004) These assumptions are not simply lists; rather they are interconnected, networked, and systemic, forming the underlying bases for corporate behavior.

These assumptions are at the deepest level of culture and constitute what might be considered a grammar of cultural principles that gives rise to two higher levels in organizational culture: its artifacts and espoused values. The artifacts are the visible products of the group or, for our purposes, some of the primitives or basic elements included in the EA. The espoused values “focus on what people say is the reason for their behavior, what they ideally would like those reasons to be and … their rationalizations for behavior,” including the mission and vision, strategies, values, goals, and objectives that are their conscious guides. Basic assumptions are the underlying theories of practice in use that actually (rather than assertively) guide behavior and inform group members about how to perceive, think about, and feel about things. Unless we dig down to the level of basic assumptions we cannot decipher artifacts, norms, and values. These assumptions are identified only through an analysis of anomalies between observed visible artifacts and the espoused beliefs and values.

As you will see, the representation of performers in the enterprise architecture currently is based on the explicit nature of organizations—representations of formal organizational charts, roles, internal and external players, and their interactions based on formal and informal agreements. In our discussions on social networks, we have distinguished espoused values from intrinsic beliefs. While building stakeholder charts tabulating various stakeholders of the enterprise and their concerns, we tend to focus on the espoused beliefs. Understanding tribal behavior requires understanding of the intrinsic assumptions and beliefs of tribes, as demonstrated in the work of Schein.

Schein’s Three Levels of Culture

In his book DEC is Dead, Long Live DEC (2004), Schein posited three levels of culture: artifacts, espoused values, and tacit values, as illustrated in Figure 2-4. The following sections provide examples of the espoused and tacit values and assumptions from Schein’s analysis of two actual companies: DEC and Novartis.

Figure 2-4 Schein’s three levels of culture

Clinical Cultural Analysis Example: DEC

Schein analyzed five tacit assumptions forming a systemic pattern in DEC’s internal relationships, as illustrated in Figure 2-5.

Figure 2-5 Five tacit assumptions of DEC’s internal culture

Each of these assumptions was originally advocated by DEC founder Ken Olsen and then was eventually incorporated into that assumption system. At the center was the assumption that work is fun and DEC was a culture of innovation. Related to this central assumption were four additional basic assumptions. At the upper left in Figure 2-5 is the entrepreneurial spirit or “rugged individualism,” where every member of the organization was in a sense an internal entrepreneur coming up with new ideas. When a new idea was proposed, there was the assumption of personal responsibility, where, in the words of Olsen and often quoted by DEC’s senior management, “he who proposes does” and that everyone can be trusted to “do the right thing.”

The entrepreneurial spirit was also linked to the assumption that truth would arise through conflict. Employees were expected to be highly volatile and even combative for their ideas. At DEC, engineers received financial rewards when their project was chosen, so there was a tremendous competition among employees to promote their ideas. Olsen established off-site meetings, or “woods meetings,” where engineers would fight each other for their ideas. The volatile nature of these meetings was the first reason why Olsen hired Schein as his consultant. However, once a concept was accepted, participants whose ideas were not selected would buy into the winners and push back on their ideas. This argument system for obtaining buy-in on ideas was supported by a kind of tenure system at DEC, where once hired, an engineer was assumed job security and a strong sense of family paternalism.

Along with the internal system was an external assumption system for how DEC interacted with its environment for survival, as diagrammed in Figure 2-6.

Figure 2-6 Five assumptions of the external environment

At the center of the external assumptions is arrogance, this being engineering arrogance, the idea that engineers, scientists and (myself being one) academics “know what is best.” With this central assumption are four associated assumptions. One that was indigenous to DEC management was that there is central control and the operations committee manages budgets for all projects. That being said, the three other major assumptions address how, through “arrogance,” problems can be solved. There is the concept of organizational idealism that reasonable people of goodwill can solve any problem. Engineers can resolve anything. This assumption is strongly linked to a commitment to customers and a dedication to solving customers’ problems. At DEC, this commitment and dedication was expressed in yearly conferences such as DECUS, a customer membership organization where customers presented both problems and ideas for DEC engineers to take on.

Finally, there was the assumption about markets as arbiter. This involved the belief that if good products were made, they would demonstrate their value without having to be strongly promoted. The latter involved a basic assumption of engineering culture that “good work speaks for itself” and that an engineer “should not have to sell himself.” Olsen directly expressed this in his attitude about sales and marketing: “Public relations and image building are forms of ‘lying’ and are to be avoided.” This idealism of engineering and dominance over sales resulted in what Schein described as a lack of “the money gene” in the cultural DNA of DEC that countered DEC’s ability to adapt to growth and changes in the business and technological landscapes. Consequently, the same assumptions that resulted in the meteoric success of DEC also underlay its eventual demise.

Clinical Cultural Analysis Example: Novartis

Schein also provides an analysis of the pharmaceutical company Novartis that stands in interesting contrast to DEC. Where DEC emphasized informality and rank and status were based on the actual job being performed by individuals, Novartis had a system of managerial ranks based on length of service, overall performance, and personal background of the individual rather than on job being performed at a given time. Thus, rank and status had a more permanent quality at Novartis; whereas at DEC one’s fortunes could rise and fall based on project.

The value set at DEC versus Novartis was seen in the contrast for how meetings were perceived. At DEC, they were places where work got done; at Novartis they were necessarily evils where announcements got made. Both corporations placed high value on individual contribution, but at Novartis one never went outside chain of command or did things out of line with what one’s boss suggested.

The tension between organizational artifacts and espoused values provides an avenue to discover the underlying assumptions of culture. In the case of Novartis, the artifact of central importance, as Schein worked with the corporation under mandate to help them be more innovative, was the problem in the distribution of his suggestions. These were sent only after they were requested rather than by the manager he gave them to in order to distribute. The rationale for this is that when a manager is given a job, it becomes the private domain of that individual. Hence, there was a strong sense of turf or ownership and an assumption that each owner of a piece of the organization would be in charge and on top of his area. Only if information was asked for was it acceptable to offer an idea. This led Schein to model the assumption system of Novartis, illustrated in Figure 2-7.

Figure 2-7 Novartis cultural paradigm

The important point here is how Schein was able to locate an underlying systematic that constituted what Jackendoff (2007) described as an underlying set of grammatical rules for social cognition, or what we consider here to be culture. Also significant is that these rule sets can be modeled, and they are consistent with a particular set of products included in some EA frameworks: operational or business rules.

Representing Culture as Business Rules

A business rule is guidance that there is an obligation concerning conduct, action, practice, or procedure within a particular activity or sphere. One definition of business rule specifies that operational or business rules are constraints on the way that business is done in the enterprise. At lower levels, rule models may describe the rules under which performers behave under specified conditions. Such rules can be expressed in a textual form, for example, “If (these conditions) exist, and (this event) occurs, then (perform these actions).”

Some business rules can be found in policy and other organizational policy and business process documentation. However, while many business rules are expressed as formal, documented rules of the business, others are hidden from view and need to be uncovered. Both types of rules constrain activity and provide schema for culturally appropriate organizational behavior.

In EA, when business rules constrain processes or activities, these rules can be associated with activity models. That is, business or operational rules can be modeled relevant to each activity, and cultural rules can thus be expressed within activities. Such activities can be decomposed into sets of constitutive activities with inheritance and documented in an activity hierarchy or tree diagram. The flow of information among these activities can then be modeled using one of the standard activity modeling methodologies such as Integrated Definition for Functional Modeling 0 (IDEF0) or Business Process Modeling Notation (BPMN). The rules can also be documented directly using one of the many rules modeling languages, although the independently modeled rules must be associated with activities through an activity model.

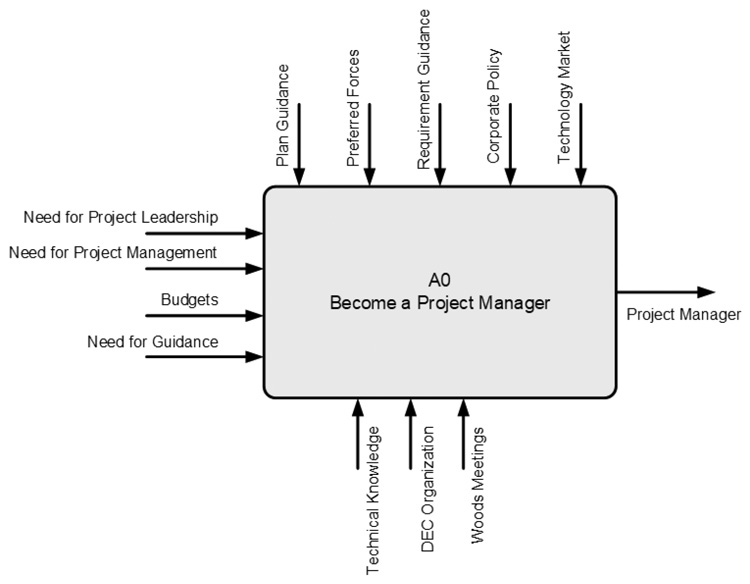

Returning to Schein’s example of DEC culture, we might model the process of becoming a project manager as follows using the IDEF0 technique: First, we construct a context diagram with inputs, outputs, controls, and mechanisms for the highest level activity in an activity hierarchy, which can be represented as shown in Figure 2-8. In this technique, rules are modeled as controls because they constrain the processes and component activities.

Figure 2-8 Context diagram for becoming a project manager

The top-level process or activity can be decomposed into component activities and documented in a hierarchy diagram, as illustrated in Figure 2-9.

Figure 2-9 Decomposition diagram

The flow of information among the component activities can be documented in an IDEF0 activity model, which includes inputs, outputs, controls, and mechanisms (ICOMS) (distributed to the component activities from those shown on the context diagram) for each component activity, as illustrated in Figure 2-10.

Figure 2-10 Activity model with ICOMs

An example of such modeling can be made from an observation from DEC culture as described by Schein. In the 1980s, one of the authors was the research director at Western Behavioral Sciences Institute (WBSI) in La Jolla, California, which focused on computer communications and included the formation of The School of Management and Strategic Studies (SMSS). The school was a program for senior executives from the public and private sectors who attended twice a year, weeklong workshops and then continued their discussions online using computer conferencing and messaging.

An interesting perk of being on the WBSI staff was often being invited to lunch with several of the management teams from the participating organizations. After a short time, Beryl Bellman, professor in the Department of Communications at California State University at Los Angeles, noticed an interesting pattern, where at lunch, when the check was presented, a number of executives got up and went to the restroom. He interviewed several of his DEC associates and learned that there was a “cultural” business rule that the highest ranking person attending such an event is responsible to pay the bill. In this case, there often were several members of DEC with equal rank within the corporation (VP level) attending the sessions, which potentially created a dilemma or competition for paying the check. This was resolvable by an associated business rule that seniority is established by project rather than rank. That is, the highest ranking person at the table was the individual of high rank that had been attending the WBSI program for the longest period of time. Thus, those at the table contextually evaluated their relative rank to others in attendance. If others were of higher rank, they remained at the table. However, if others at the table were of equal rank within the company, the person to pay the bill was the person who had been attending the SMSS program the longest. In this case, those of equivalent rank often left the table when the bill was presented, allowing the most senior among them to take out his or her credit card. This cultural business rule structure could be modeled as illustrated in Figure 2-11. This rule could be associated with the (informal) process of Having Lunch.

Figure 2-11 Cultural business rule

This business rule corresponds to the assumption system structural schema Schein described for internal integration in the interaction between the two cultural assumptions of family paternalism and truth through conflict. On the one hand, there is the strong integrative function expressed in the assumption about the DEC family, and on the other hand, of the “truth through conflict” when decisions are made. In this case, there is a “pushing back” and “buying in” rather than openly negotiating status in the presence of non-family members.

Culture as a Emergent Phenomenon

An enterprise arises from local interaction of often independent units that exist within a common environment. Each unit or entity interacts with its immediate environment according to a set of low order rules. The combined effects of these lower order interactions within an environment give rise to higher order organizational phenomenon or organizational culture. Culture emerges from localized interactions. As culture is grounded at the local level, culture is highly resistant to change.

So organizational culture is an emergent phenomenon. It resembles the process of stigmergy, which is a kind of indirect communication and learning in the environment found in social insects. It is a well-known example of self-organization, providing vital clues to understanding how the components can interact to produce a complex pattern. Stigmergy is a form of coordination through changes in an environment. Following an example by Depickère et al. (2004), if we were to take a bucket of dead ants and scatter them about in a room and then throw in a bucket of live ants afterward and seal off the room, in a few days when we look inside we would find all the dead ants in a single pile. Depickère and her associates conjectured a probabilistic explanation of this behavior: Faced with a dead ant, an ant picked it up with probability inversely proportionate to the number of other dead ants in the vicinity. While carrying a dead ant, the ant put it down with probability directly proportional to the density of dead ants in the vicinity. Thus, the coordinated behavior of piling dead ants in a single pile resulted from a simple local rule controlling the behavior of a single ant. The piling behavior is accounted for without postulating communication between the ants. Researchers developed an experiment using robotic ants programmed with a swarm instruction based on the living ants and produced similar consequences.

Since enterprise culture emerges from local interactions, changing culture entails respecifying local level rules rather than simply imposing change from the top. Creating EA proffers a mechanism to initiate positive change. The underlying local level rules giving rise to an emergent organizational culture can be modeled to help us understand the implications they have on enterprise culture at every level and to identify the rules that need to be modified to effect change.

We have discussed how the behavior of individuals can be described as sets of cultural “business rules.” These sets of rules make up different types of strategic interaction games, as exemplified in the classic example of the prisoner’s dilemma. However, in game theory, focus has been on one game at a time. Using evolving automata, cognitive behavior is modeled across multiple games. This points to a games-theoretic model of culture as simultaneously playing out a series of games as constituting ensembles that impact the strategy for any particular game.

In this context, Axelrod (1997) characterized cultures as vectors with agent attributes. By vectors, he considered cultural diffusion as a simple model capable of complex behaviors. This entails the effects of empirical opinion vectors promoting cultural diversity in cultural models. As described in a Wikipedia entry “we find that a scheme for evolving synthetic opinion vectors from cultural ‘prototypes’ shows the same behavior as real opinion data in maintaining cultural diversity in the extended model; whereas neutral evolution of cultural vectors does not.”

The development of a shared culture of common attributes emerges when these agents become more like those with whom they interact and also when they interact with those who share similar attributes. This recommends a new type of explanation for social and cultural phenomenon. As Epstein and Axtell (1996) argue, we should reinterpret the question of explanation by asking “can we grow it?” They maintain that such modeling “allows us to ‘grow’ social structures … demonstrating that certain sets of micro- specifications are sufficient to generate the macro-phenomena of interest.” They argue, with this in mind, that social scientists “are presented with ‘already emerged’ collective phenomena and … seek micro-rules that can generate them.” The point here is that by locating the underlying business rule schema that drives social contextualized behaviors, we can, in a sense, run computational models that allow the traceability suggested earlier between business process proposals and cultural assumptions that are entailed and informed and can be incorporated into EA.

Culture from Multiple Perspectives

A full understanding of any organizational/enterprise culture involves seeing it from multiple perspectives. Organizational theorist Joanne Martin (2002) argues for a three-perspective view of culture. First is the integration view, where every member of the organization shares culture in an enterprise-wide consensus. When there is lack of consensus, either remedial actions are taken or there are suggestions that those who do not agree leave the organization. This view is expressed in solidarity and esprit de corps. Next, there is the differentiation or subcultural view. This involves a focus on inconsistent interpretations based on subculture and stakeholder perspectives and entails a loose coupling between representations of the culture as expressed to outsiders versus insiders. We refer to this perspective as tribal views. Then there is the fragmentation perspective that focuses on ways in which organizational cultures are inconsistent, ambiguous, and multiplicitous and in a state of flux. This fragmentation addresses the multiplicities of interpretation that do not coalesce into a collectivity-wide consensus of an integration view nor create subcultural consensus of the differentiation perspective.

Each view entails different sets of assumptions, and though each is simultaneously present in every culture, at any given time one of the perspectives can have prominence over others. So when presenting itself to the outside, the integration view shows esprit de corps, and enables members to see themselves as part of a common culture despite the differences within. In the differentiation view are the organizational stovepipes and internal competition. There is always a danger of subcultures becoming hostile and fighting against each other, turning themselves in contra cultures.

In the airport example discussed throughout this book, we need to keep in mind these perspectives and that each entails a different level of emergence through interlocking sets of game ensembles. There are the integrated emergent properties of the coherent culture of the airport as an entity, the divergent subcultures emerging in the context of the various functional organizations of the airport (management, flight control, concessions, TSA, and so on) that represent different tribes within the organization, and the emergence of fragmented cultures at the shop floor, with the local level politics and “how we are going about doing things around here.” There is a concatenation of these at any given time, yet they can be modeled with the effects of culture to better understand how they impact the EA of an airport.

Summary

We have shown here that organizational culture can be incorporated into an EA project using both business rules and activity or process models. These rules form the logic or grammar for the rules set that, like grammar, are finite but provide for virtually an infinite variation of surface representations, like the sentences of a language form deep structure. Likewise, these rules are syntactical and have form and function. These syntactical rules are the grammatical and transformational rules that enable us to determine whether and how an architectural artifact can be interpreted, accepted, or rejected. We will return to this concept in the following chapters as we observe the impacts of culture, climate, and tribes in our case study.

Questions

1. Describe the organizational or corporate culture that you must deal with to obtain information relevant to your enterprise architecture.

2. Describe cultural constraints—social, political, interpersonal, value systems, and so on—that impact your ability to obtain information, and how you plan to deal with them.

3. Using the grid/group model for measuring culture, how would you place the organizational culture of your enterprise?

4. How is culture represented in the different architecture viewpoints?

5. Be able to differentiate the organizational climate or atmosphere in your enterprise from its organizational culture.

6. What is the relationship between communication networks and organizational culture?

7. We discussed how culture assumption systems could be modeled as a special instance of business rules. Such rules can be expressed in a textual form, for example, “If (these conditions) exist, and (this event) occurs, then (perform these actions)” or graphically shown using a flow diagram. Identify some cultural assumption relationships within your or a client’s organization and provide a rule schema for some cultural activity scenario using either a textual or a graphical representation.

8. What steps would you engage in to diagnose organizational culture problems, and how would you begin to change them?

References

Ackoff, Russell L. 1981. Creating the Corporate Future: Plan or Be Planned For. New York: Wiley.

Ackoff, Russell L. 1994. The Democratic Corporation: A Radical Prescription for Recreating Corporate America and Rediscovering Success. New York: Oxford University Press.

Ackoff, Russell L., Herbert J. Addison, and Andrew Carey. 2010. Systems Thinking for Curious Managers: With 40 New Management F-Law. Axminster, UK: Triarchy Press.

Axelrod, Robert. 1997. “The Dissemination of Culture: A Model with Local Convergence and Global Polarization” Journal of Conflict Resolution (41) 2: 203–26.

Bendor, Jonathon, and Piotr Swistak. 2001. “The Evolution of Norms.” American Journal of Sociology, 106(6): 1493–1545.

Bittner, E., and H. Garfinkel. 1967. “‘Good’ organizational reasons for ‘bad’ clinical records,” in Garfinkle, Studies in Ethnomethodology. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Cross, Rob, Tim Laseter, Andrew Parker, Guillermo Velasquez. 2006. “The Basis for Creating Network Links.” Harvard Business Review, November 2006.

Cross Rob, J. Liedtka, and L. Weiss. 2005. “A practical guide to social networks.” Harvard Business Review (3): 124–32.

Depickère S., D. Fresneau, and J.L. Deneubourg. 2004. “A basis for spatial and social patterns in ant species: dynamics and mechanisms of aggregation.” Journal of Insect Behavior, 17(1): 81–97.

Douglas, Mary. 1970. Natural Symbols: Explorations in Cosmology. New York: Pantheon Books.

Douglas, Mary, and Aaron Wildavsky. 1983. Risk and Culture. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Epstein. Joshua. M., and Robert L. Axtell. 1996. Growing Artificial Societies: Social Science from the Bottom Up. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Garfinkle, Harold. 1967. Studies in Ethnomethodology. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

Giddens, Anthony. 1986. The Constitution of Society: Outline of the Theory of Structuration. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Gladwell, Malcom. 2000. The Tipping Point: How Little Things Can Make a Big Difference. Boston: Little Brown & Co.

Gudykunst, William, and Young Yun Kim. 2002. Communicating with Strangers: An Approach to Intercultural Communication. New York: McGraw-Hill Humanities/Social Sciences/Languages.

Hofstede, Geert, Gert Jan Hofstede, and Michael Minkov. 2010. Cultures and Organizations, Software of the Mind: Intercultural Cooperation and Its Importance for Survival, 3rd Ed. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Holland, John H. 1996. Hidden Order: How Adaptation Builds Complexity. New York: Perseus Books.

Hymes, Dell. 1977. Foundations of Sociolinguistics: An Ethnographic Approach. London: Tavistock Press.

International Phonetic Association. 1999. “Phonetic description and the IPA chart,” in International Phonetic Association, Handbook of the International Phonetic Association: A Guide to the Use of the International Phonetic Alphabet. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Jackendoff, Ray. 2007. Language, Consciousness, Culture: Essays on Mental Structure. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Kunda, Gideon. 2006. Engineering Culture: Control and Commitment in a High-Tech Corporation. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Livingston, Eric. 2016. Ethnographies of Reason. New York: Routledge Kegan & Paul.

Lorenz, Edward N. 1963. “Deterministic Nonperiodic Flow.” Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences, (20): 130–41.

Lorenz, Edward N. 1993. The Essence of Chaos. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Lynch, Michael. 1985. Art and Artifact in Laboratory Science: A Study of Shop Work and Shop Talk in a Research Laboratory. New York: Routledge Kegan & Paul.

Martin, Joanne. 2002. Organizational Culture: Mapping the Terrain. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Papa, M.J., T.D. Daniels, and B.K. Spiker. 2008. Organizational Communication: Perspectives and Trends, Rev. Ed. Thousand Oaks CA: Sage Publications.

Pettigrew, Andrew M. 1979. “On Studying Organizational Cultures.” Administrative Science Quarterly (24) 4: 570–81.

Romney, Kimball, and Roy D’Andrade. 1964. “Cognitive Aspects of English Kin Terms.” American Anthropologist, (66)3: 146–70.

Rumelhart, David E., James L. McClelland, and PDP Research Group. 1986. Parallel Distributed Processing: Explorations in the Microstructure of Cognition, Vol. 1: Foundations. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Schein, Edgar. 2001. Organizational Culture: Mapping the Terrain. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Schein, Edgar. 2004. DEC is Dead, Long Live DEC: The Lasting Legacy of Digital Equipment Corporation. Oakland, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Schein, Edgar. 2010. Organizational Culture and Leadership, 4th Edition. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Schneider, Benjamin, and Karen Barbera, eds. 2014. The Oxford Handbook of Organizational Climate and Culture. New York: Oxford University Press.

Seel, Richard. 2000. “Culture and Complexity: New Insights on Organisational Change,” in Organizations & People (7) 2.

United States Senate, Staff Report. 2014. The Air Force’s Expeditionary Combat Support System (ECSS): A Cautionary Tale on the Need for Business Process Reengineering and Complying with Acquisition Best Practices.

Weick, Karl. 1977. “On Re-Punctuating the Problem in New Perspectives on Organizational Effectiveness,” in Paul S. Goodman and Johannes Pennings, eds., New Perspectives in Organizational Effectiveness. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Wilcock, Keith. 2004. Hunting and Gathering in the Corporate Tribe: Archetypes of the Corporate Culture. New York: Algora Publishing.