“Mere color, unspoiled by meaning, and unallied with definite form, can speak to the soul in a thousand different ways.”

–Oscar Wilde

CHAPTER 9

PROJECTORS

In my opinion, there’s an extra layer of believability—a tangibility, if you will—to using practical effects in image-making as opposed to relying heavily on creating effects in post-production. My postproduction work is limited by the breadth (or lack) of my imagination, which is why I try to get as much as I can in-camera. For example, one time I was projecting a lighting bolt on my subject’s face and the lightning illuminated her eye in a really beautiful way (seen in the gallery at the end of the chapter). I wouldn’t have thought to create that effect if I were relying on Photoshop to make the image. Projectors are a fantastic lighting tool that allows you to create custom shapes and colors to accent your images, enabling you to create vibrant in-camera effects. This chapter will explore several ways to use projectors as a lighting tool in photography.

PROJECTING ON THE BACKGROUND

I first used a projector as a lighting tool in 2015 in a fashion story about vacation getaways. It was February in Ohio, and the only available outdoor options were dark skies and snow or ice-covered surfaces, so I projected exotic locales on a wall behind the model. The only projector I had access to was old, dim, and would stop working every time it was bumped. Despite all the elements working against me, I pulled off an image I was happy with (Figure 9.1).

Because the projector was dim, and since I needed the projector to be far enough away from the background that the image filled my frame, I had to completely darken the room that I was shooting in to keep the room light from diluting the projection (Figure 9.2). All that is to say that when it comes to selecting a projector to use in a shoot, go for the brightest one you can find. I have since purchased an Epson EX3240 projector; it was basically the brightest, highest-rated projector that I could find (3200 lumens) without spending a fortune (less than $400).

Figure 9.1 For this fashion story about vacation getaways, I projected exotic backdrops with the projector.

Figure 9.2 The projector I first used was so dim that I had to completely black out the room to keep the ambient light from diluting the projection.

Figure 9.3 I mount my projector to a laptop stand with duct tape, allowing me to position my laptop horizontally or vertically.

The problem with using a projector as a light source is that it’s tough to get it into desirable positions. Projectors are designed to be stationary, and all mounting systems that I have found for them are designed accordingly. Ideally, I would have the projector mounted onto a ball head so I can position it at any angle. The best solution I have found is a laptop stand (Figure 9.3). The stand rotates on a single axis point to a 90-degree angle, allowing horizontal and vertical positions. I use duct tape to attach the projector to the stand. If you happen to have a more efficient solution, by all means let me know.

There are a number of ways to use projectors in a shoot. You can aim the projection behind the model, as I did in Figure 9.1; you can aim it onto both the model and background; or you can position it in such a manner that it falls on the subject but not the background. Once you determine where you will aim your projector and you begin calculating your exposure, make sure to keep track of what the ambient light in the room is doing. In Figure 9.4, you can see how the tungsten light in the next room affected the ambient exposure.

Next, you need to check the resolution settings on the projector. In Figure 9.5, you can see that the projected image on the left is rendering poorly, resulting in pixelated shapes. One workaround can be shifting the projector lens slightly out of focus. Another is lowering the sharpness in the menu settings of the projector. Side note: I’ve found that if the projector is closer to the subject, there is little-to-no pixelation.

Figure 9.4 When using a projector, make sure that the ambient light in the room isn’t interfering with the projector image, as indicated by the orange light in the left image.

Figure 9.5 By lowering the sharpness in the menu of the projector or by shifting the projector lens out of focus, you can avoid projecting large pixels on your subject.

PROJECTING ON BOTH THE SUBJECT AND THE BACKGROUND

In this scenario, I was doing a photo shoot for a local clothing designer’s new collection. The designer had made several floral patterns that she printed onto the fabrics she used to make the garments. We decided it’d be cool to also project her designs onto the model and clothing for the shoot.

I began by firing up the projector and cutting the room lights. To take advantage of every lumen in the projector, it’s best to align the projector with the orientation of the camera, allowing it to be as close to the subject as possible. This means that since I was shooting a vertical portrait orientation, the projector needed to be positioned at a 90-degree angle to project a vertical image.

When projecting an image on both the subject and the background, the subject’s shadow will appear on the background (Figure 9.6). As we learned in chapters 1 and 7, shadows are fantastic placeholders for other colors. Rather than trying to position myself to a place where I didn’t see the model’s shadow on the background, I added a fill color. I selected a cyan gel to complement the magenta and navy garments, and to brighten up the color palette. A warmer color would neutralize the garment colors and a darker shade of blue would’ve been too visually heavy with the already dark-colored garments. I gelled the softbox and positioned it at a high angle to the right of the subject (Figure 9.7) in order to fill in the heavy shadows with soft cyan light (Figure 9.8).

Figure 9.6 When projecting an image onto both the subject and the background, a shadow will be cast on the background.

Figure 9.7 I added a cyan-gelled softbox to the right of the subject at an elevated angle to fill in the shadow created by the projector.

Figure 9.8 The RAW file. The shadows created by the projector are now cyan.

Note the camera and flash settings in Figure 9.9. The projector needed to be about 15 feet away from the subject to light her from head to toe. This meant that the projected image was not very bright. As a result, my shutter speed was down to 1/40 at f/3.5. I used an ISO of 500 to get a good exposure for the projector. This meant that my flash had to be powered down to 1/64 to not overpower the projector. Had I not needed to shoot a full-body shot, I would have been able to position the projector much closer to the subject. A brighter projection means using a faster shutter, smaller aperture, and brighter flash output.

When I opened the file in Lightroom (Figure 9.10), I started by making a gradient adjustment, beginning at the bottom of the image, bumping up the shadows. Next, I made a series of curve adjustments to flesh out the colors in the file. Then I used the targeted action tool in the HSL panel, adjusting the hue and luminance of blue/cyan and red/purple/magenta. I finished off the image with a slight increase to dehaze and a tweak to the overall colors in the CC panel (Figure 9.11).

Figure 9.9 The Lighting diagram. The projector was about 15 feet from the subject, resulting in a low-light scenario. As a result, I needed a slow shutter, wide aperture, and low flash output.

Figure 9.10 The Lightroom settings. I made a gradient adjustment from the bottom of the image, raising the shadows. Then I adjusted the colors in all three panels: curves, HSL, and CC.

Figure 9.11 The final shot. The colors and patterns from the projector and strobe help complement those of the garments.

PROJECTING ON THE SUBJECT

Many of the images that I use in my projections I created in Photoshop. I made simple shapes and patterns involving a range of colors, such as the orange circle on a blue background seen in Figure 9.12. You can see how this projection looks when projected on both the subject and background in Figure 9.13. In Figure 9.14, you can see that my subject is about 6 feet away from the wall and about 3 feet from the projector. Note how by simply taking a few steps to the side and changing my orientation in relation to the model, my camera frame captured the unlit portion of the wall, resulting in a black background (Figure 9.15). No gel gobo in the world will give you a transition that clean.

Figure 9.12 I made a number of simple shape and color designs to use as projections, such as this orange circle on blue.

Figure 9.13 The projection on both the subject and the background.

Figure 9.14 Here is the pattern projected on the subject, who is seated 6 feet from the background. By stepping a few feet to the side and changing my orientation to the model, my camera frame captured the unlit portion of the wall, resulting in a black background.

Figure 9.15 The pattern projected on my subject but not the background.

Another way to create images for projection is to modify existing imagery. I searched Google for my source images, making sure to set the search parameters to only look for large images. You can also set the parameters to look for openlicense images, which is important if you’re using a source image in a way that it will still be recognizable (which I rarely do). Most of the time, I am just using the source image as a way to quickly create a pattern, rendering it unrecognizable in the final image.

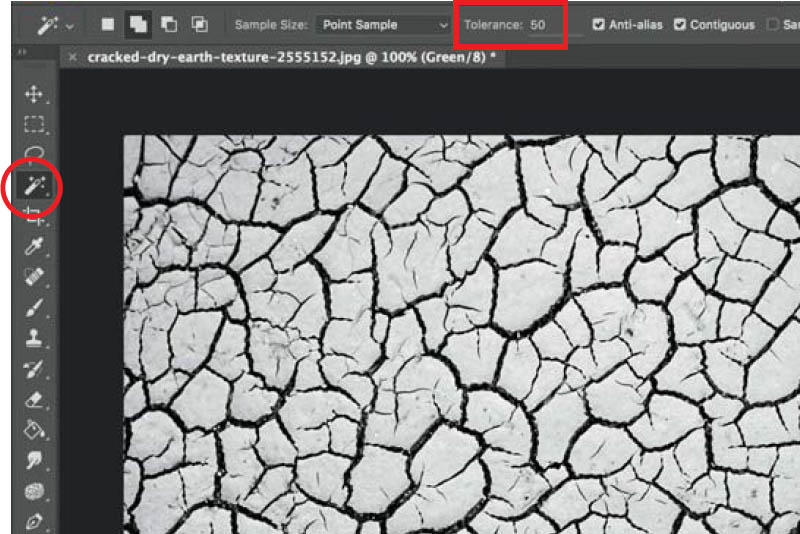

For example, I found an image of cracked earth that I liked and opened it in Photoshop (Figure 9.16). I selected the magic wand tool, setting the tolerance to 50, which allowed me to quickly select most of the cracked portions of the image (Figure 9.17). Had I wanted to make sure I got all the cracked areas, I could Option-click and select the “similar” option to get every black crack in the image, but my initial selection worked just fine. Next, I created a fill layer, using the “solid color” option (Figure 9.18) and set the color to red (Figure 9.19). When I delete the source-image layer, I am left with just the red cracks (Figure 9.20). I finish by making another fill layer, this time selecting black, and making it the bottom layer (Figure 9.21). I flatten the image and save it as a jpeg. The only part of the original image left to project on my model are the vibrant red cracks (Figure 9.22).

Figure 9.16 I use source images from Google to create custom projections.

Figure 9.17 Once I save an image and open it in Photoshop, I use the magic wand tool (set to a high tolerance of 50) and select the black cracks.

Figure 9.18 I create a solid color fill layer.

Figure 9.19 I set the color to red.

Figure 9.20 I delete the background layer.

Figure 9.21 I create a new, black fill layer, and position it as the bottom layer. Then I flatten the image and save it as a jpeg.

Figure 9.22 The final custom pattern.

Figure 9.23 The Lighting diagram. Because I am not shooting full body in this scenario, my projector can be positioned closer to the subject.

I’ve made dozens of patterns that I (or my model) will select from when making an image. Once an image is selected, I hook up my laptop to the projector, and set my projector at a 90-degree angle (assuming I’m shooting a vertical composition). In this scenario, my portrait composition was from the waist up or closer, meaning I can have the projector within 7–10 feet of the subject. This creates a brighter projection, so I use a faster shutter speed, a lower ISO, and a smaller aperture to eliminate any ambient room light (Figure 9.23).

In Figure 9.24, I’ve projected the cracked earth image onto my subject. I added a cyan-gelled softbox at a 45-degree angle from the camera, leaving the camera side of the subject in shadow. I position my projector at the same angle as the main light, then take a test shot and determine whether or not to move anything. One of the best parts about using projectors as a light source is that you can adjust the attributes of a projection in just a few seconds. Since my projector is already connected to my laptop, I can open the projected image in Photoshop and shift the hues, or even use the transform option to adjust thickness or rotation.

I typically pair a monochromatic projection with a gelled light in a complementary color. As I mentioned in the shutter drag technique, when using a dutone image comprised of a cool and a warm color, you can dramatically change an image in post-production by adjusting the white balance. For this image, I was able to emphasize the red by raising the highlight area of the red tone curve and adjusting the red and green primary sliders in the CC panel (Figure 9.25). I cranked up the dehaze to add a dark drama to the overall image and bumped up the clarity to add muscle definition (Figure 9.26).

Figure 9.24 The RAW file. The colors are there but need to be fleshed out.

Figure 9.25 The Lightroom settings. I drew out the reds and blues by using the dehaze slider and camera calibration panel. By increasing the clarity, I was able to emphasize the subject’s muscles.

Figure 9.26 The final shot. A quote from Pineapple Express comes to mind: “I’m gonna flex and bust out of here. . . .”

Have fun experimenting with projections. Play with projecting video or a moving slideshow while making multiple exposures, which is what I did in the chapter-opening image. Try positioning the projection on the shadow area of the subject (Figure 9.27. Any of the techniques from prior chapters can be used in combination with projections.

Figure 9.27 Experiement with positioning your projection on the shadow area of your subject.

Figure 9.28 Since projectors are a continuous light source, you can use shutter drag to change your image.

Personally, my favorite way to incorporate projectors into my image-making is to use it in combination with shutter drag, which works since the projector provides a continuous light source (Figure 9.28). Depending on the type of projector you are working with, you can get different effects with shutter drag. Look what happened when I used a short throw projector (which is used to project large images in short distances) (Figure 9.29). Note that it wouldn’t work to use shutter drag in combination with a strobe-based alternative to a projector (such as a Light Blaster), because it’s not a continuous light source.

Figure 9.29 When you use shutter drag in combination with a short throw projector, the effect is different than when using a traditional projector.