11. Eco-Engineering: The Grass Is Always Greener

Yes, the title of this chapter has a dual meaning. Among senior executives at global corporations, eco-engineering is already seen as a strategic imperative—even though the practice of eco-engineering is not yet clearly understood by engineers. At the same time, many companies feel constant pressure to prove that their “green” initiatives are greener than their competitors’, leading to an upward spiral in greenwashing.

The net result is confusion. It can be difficult for engineers, executives, and consumers to distinguish between an environmentally responsible project and a plain old-fashioned PR grab. If you’re an engineer who’s really interested in making a positive environmental impact, what should you focus on? Here are a few suggestions, based on lessons learned from the real world of eco-engineering.

Carbon Neutrality: Good Start but Not Enough

Corporate sustainability leaders tend to be a collaborative group. They are open to sharing ideas, swapping stories, and growing their networks of colleagues in other companies. And that’s a great thing, because those of us who deal with corporate sustainability on a daily basis know we’re in uncharted territory and that we’re all learning as we go. We understand it’s in everyone’s best interest if the overall economy becomes more sustainable. After all, when it comes to climate changes there aren’t winners and losers—ultimately we’ll either all win or all lose.

For example, let’s say your company magically reduces the environmental impact of its operations to nothing so that you’re able to deliver your products and services with no impact of any kind. But in the excitement your company decides that you have created such a big advantage through your eco-effectiveness that you better keep it a secret and not share your magic with anyone else. In this case, how much better off is the world? Does erasing the impact of one company make a big difference? Unfortunately, no.

Which brings us to the subject of carbon neutrality, the term often used to describe the goal of corporate efforts to lessen companies’ impact on the environment. No company can reduce its greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions to zero, so the idea is that Organization A pays Organization B to plant trees, increase energy efficiency, create green energy, or do something else with a positive impact on GHG emissions, thus offsetting Organization A’s own carbon emissions.

Many companies have centered their environmental strategy on a goal of achieving carbon neutrality. They are generally doing some efficiency projects, purchasing some green energy, and offsetting the rest. But we’ve been looking at product and service lifecycles, and we know the part that’s within your four walls may be only a small part of your overall impact. What about your supply chain? What about your products in use at your customers’ facilities? What about your products at the end of their useful lives?

So, carbon neutrality misses the point. It’s good for companies to invest in others’ good deeds, but right now it is absolutely critical that companies invest in creating more sustainable versions of themselves.

Yes, we absolutely need a dramatic increase in zero and low-carbon energy sources, but we use so much energy that that won’t be enough. We need improvements in basic efficiency—but that’s going to be good for only a 20% to 40% improvement, and it won’t be enough either. If we want to make serious headway and still have the quality of life we strive for, we’re going to need a lot more, and part of that “more” is going to have to be some radical innovation and improvement in the design, manufacture, and delivery of all the products, services, and infrastructure that make up our economy.

More than ever, we need the innovation that comes from competition and open markets. We need companies that view climate change not as a threat but as an opportunity—and are pursuing it with the enthusiasm that big opportunities engender. We need companies to go beyond carbon neutrality to something we, the authors, call “carbon advantage.”

You can create a carbon advantage for your company in two ways. First, you can use efficiency and resource reduction to provide a fundamental cost advantage in your operations and products. Second, you can use innovation in green products and services to offer customers a competitive advantage, thus differentiating your offerings.

The good news is there’s lots of advantage to be had. Companies that have created more eco-friendly goods—such as carmaker Toyota Motor Corporation and carpet maker Interface—are increasing their market share and improving their business performance.

But more important, there’s increasing evidence that we’re on the verge of a new, virtuous business cycle: Companies seeking sustainability are looking for sustainable products and services, which provides further opportunities for sustainable companies. As a result, products and services that can help customers improve their own sustainability will be in increasing demand, creating the opportunity for a major shift in market share and a net reduction in business impact on the environment.

Keep your eyes open and you’ll see more examples of companies achieving competitive advantage through more sustainable products, services, and operations. Consider General Electric, which noted in May 2007 that revenue for its portfolio of eco-focused products surged past $12 billion in 2006, while the value of its order backlog rose to $50 billion. Chief Executive Jeff Immelt has said the company’s Ecomagination campaign has turned into a sales initiative unlike anything he’s seen in his 25 years at the company.

Wal-Mart Stores sees the possibility of competitive advantage through increased efficiency and lower cost by reducing product packaging throughout its supply chain. Boeing knows the efficiency advantage of its new 787 Dreamliner can bring savings today, and the value of that efficiency will only grow as awareness of environmental impact grows. At Sun, we’ve seen the eco advantage in sales of our energy-efficient servers, and as our customers ramp up green IT procurement, this advantage should grow.

In contrast, if Toyota had directed its environmental strategies solely on carbon neutrality, it is unlikely the company ever would have built the Prius. The same goes for the Sun, Wal-Mart, and GE examples.

So, let’s not get too hung up on carbon neutrality when carbon advantage can take us so much further. Carbon neutrality is a step in the right direction, but for many companies it’s only a very small part of the overall impact they could have. It’s in the best interest of those companies, as well as our collective best interest, that they take a broad view and prioritize appropriately across all of their potential environmental opportunities.

At the end of the day, when companies compete on sustainability, the planet will be the big winner.

Greenwashing and Green Noise

It’s getting harder for engineers—and consumers—to distinguish between genuine eco initiatives and green hype, and that is a serious threat to eco-engineering. As an engineer, it may prevent your idea from being taken seriously within the company or being understood by your customers. More importantly, if your company is unclear or overly aggressive in marketing the eco benefits of your products, there may even be a negative backlash.

Greenwashing is what corporations do to look more environmentally friendly than they actually are. And lots of corporations are doing it. One recent study examined 1,018 consumer products bearing 1,753 environmental claims, and found that of the products scrutinized, all but one made claims that were demonstrably false or that risked misleading intended audiences.1 In fact, greenwashing has become so prevalent that CorpWatch, a U.S.-based watchdog organization, now presents Greenwash Awards to “corporations that put more money, time and energy into slick PR campaigns aimed at promoting their eco-friendly images, than they do to actually protecting the environment.”2

Green noise is related but slightly different. It refers to the information overload about eco-related products and services from corporations, columnists, researchers, market analysts, reporters, and even friends and relatives. The result of too much information is that everything turns to static. Biodiesel, fuel cells, polyvinyl chloride, sustainability, footprint, all-natural, biodegradable, organic—eventually the words turn to mush and become meaningless.

What can an engineer do to protect against greenwashing and keep consumers interested in making more environmentally responsible purchase decisions? Here are a couple of suggestions.

Measure and Label

Real data about environmental impact can help fight both greenwashing and green noise. A case in point is the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) ratings on new cars. Consider it from the consumer’s perspective: You’re aware of our climate changes, you’re not super-rich, the price of gas has just spiked to another record high, and you’re shopping for a new car. It’s a pretty safe bet that you’re taking a look at the stickers on the car windows that tell you how many miles per gallon you’ll get. In the United States, you’ll see two numbers: a “city” number and a “highway” number. Obviously, you don’t drive on only one or the other of these, but you have a good sense of your driving patterns, so you know how to weigh these numbers in your decision. And you feel good about the fact that a more efficient car is a double win: It lowers your environmental impact and saves you some cash in the process.

The EPA rating is a simple and obvious example—and you’d expect that similar energy-consumption labeling would be available for most consumer electronics products. You’d be wrong. Let’s say a new computer is next on your shopping list. Maybe you’re buying a new PC for home or a new server for your company. You see that there are lots of eco-rating schemes: Energy Star, 80 Plus, EPEAT, and Climate Savers Computing. With all these rating systems, it must be easy to find out how much power a new PC or laptop will actually use, right? Turns out the answer is no for PCs, and as you go through your day you’ll find many other examples where the energy use is not readily available.

The lack of hard data about power makes it harder to make sound purchase decisions; it frustrates people who want to be environmentally responsible; and it may even cause them to make poor decisions in related areas. For example, earlier in the book we talked about the need to cool servers, storage, and network gear in the data center. Without accurate energy numbers, the only thing a cooling engineer can do is oversize the cooling capacity, thus knowingly selecting a less-efficient design.

We’ve heard a couple of arguments about why this data isn’t available. The first is that power varies by application and utilization. That’s true for cars as well, and the answer there is to provide more than one data point and let customers extrapolate their own experience. The second is that there are lots of configuration options, and the power varies depending on the exact set the customer chooses. Again, we think customers can deal with the data—let’s give it to them.

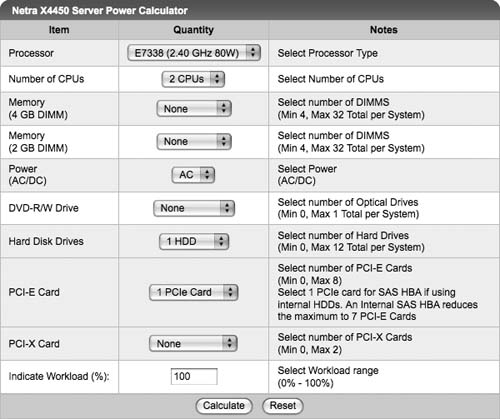

One approach to dealing with the complexity of some products is to use online power calculators, such as the one shown in Figure 11-1. It’s not as simple as a sticker on a car window, but then again, these products aren’t as simple as an already built and configured car. An online power calculator lets customers play with different configurations and understand the range of energy impacts that result from their decisions.

Figure 11-1 A Power Calculator for the Netra X4450 Server

With consumers facing numerous energy challenges, they deserve to have an accurate estimate of how much energy the products they buy will use. As engineers, we have the power to give them that information. As we’re designing the next generation of power-consuming products, let’s take the time and expend the effort to provide hard data about power consumption, and to support processes that standardize the way that data is presented to consumers. Only when we provide open, accurate data on all of the environmental aspects of products will we get the kind of green procurement and consumer behavior that we really need.

Read “The Six Sins of Greenwashing”

We suggest that all engineers take the time to read “Two Steps Forward: The Six Sins of Greenwashing,” by Joel Makower.3 It examines environmental claims made in North American consumer markets and finds, as we mentioned earlier, that the vast majority are deceptive, misleading, or simply untrue. The report then describes six patterns in greenwashing and provides recommendations for consumers as well as for marketers.

The key takeaway for engineers is that it’s time to get more actively involved in the way the products you design are marketed. The time-honored tradition of throwing finished products over the fence to marketing and PR must come to a close. Insist on reviewing the promotional materials and press releases that are being prepared for your products and make sure all claims are accurate and truthful. Total honesty doesn’t have to conflict with promotional goals; in fact, a lack of honesty usually backfires in the marketplace.

One idea is to have a technical eco lead for each product. This person would be in charge of the official eco scorecard for the product and would be the source of true data for marketing. Ideally, this person would also be required to approve all public eco claims before they go out through the marketing department. This may sound far-fetched for your organization, but we’ve seen examples of it working.

Measuring and Sharing with OpenEco

One of the key themes of this chapter has been the importance of communities, sharing, and transparency to the success of eco efforts and our overall progress as a society. Within that context we’d like to highlight one of our own projects that touches on all of these themes, as well as some of the key community and intellectual property (IP) issues discussed in this book.

OpenEco.org is an online community and Web site sponsored by Sun. We built OpenEco to help organizations measure and lower their GHG emissions, and to make it easy for them to share the data with others. You can calculate direct (Scope 1) GHG emissions from natural gas combustion and indirect (Scope 2) GHG emissions resulting from the use of purchased electricity. The calculation methodology is consistent with the World Resources Institute (WRI) Greenhouse Gas Protocol; the site also leverages resources such as those provided by the EPA Climate Leaders Program to help organizations assess performance measures using common standards.

Figure 11-2 shows a simple formula, which is consistent with the WRI GHG Protocol, for calculating GHG emissions.

Figure 11-2 Formula for Calculating GHG Emissions

![]()

“Originally, we built the core of the measurement tool to help measure and track our own GHG emissions, but we soon realized that everyone else must be facing the same challenges we were,” says Lori Duvall, who was instrumental in establishing OpenEco. “We felt a standard methodology was needed because most GHG analysis today is done with spreadsheets or using proprietary tools and can require significant investments in consulting services. We wanted something simpler, less expensive, and more accessible.”

All too often, according to Duvall, proprietary GHG analysis tools require engineers to understand many accounting practices and be able to identify the right conversion factors to use in their calculations. Not only does this discourage many organizations from assessing their GHG impacts, but it also means that results are rarely shared outside an individual organization.

“What we recognized was that the scavenger hunt of finding the underlying data is specific to each company, but the calculations and the tables of common data they use aren’t,” says Duvall. “The data management that you need to do to update each month and track your progress against your goals shouldn’t be a unique challenge for every organization either. Gil Friend from Natural Logic helped us generalize what we’d done in a way that would scale and apply to others, and we created OpenEco.org to give everyone a much easier way to get going.”

The site also provides a way to compare your GHG emissions with those of other companies in your area, or to determine your GHG per office employee, since it normalizes all of the data and has built-in tools for making comparisons. Doing this kind of comparison is nearly impossible today outside of OpenEco, and is an important step in helping organizations understand where to focus their attention. Use of the site is free, with one caveat: You have to be willing to let others compare against your data. You don’t have to attach your name to the data (it can be anonymous), but the data has to be visible for others to use.

“OpenEco isn’t a complete GHG tool yet,” says Duvall, “but it covers buildings of all kinds, and other sources will be added quickly by Sun and the community. We think it’s a great example of how corporations can help harness the power of communities for a common cause—and deliver a useful tool that promotes openness and transparency in a way that’s completely consistent with business objectives.”

We strongly believe that business and social responsibilities are closely aligned. We’re proud of the progress our own company has made in the area of “transparency,” from both a business and an environmental perspective, and we intend to continue to pull back the curtain so that everyone can see what we’re doing to promote a sustainable and responsible approach that creates value for the ecosystem and our stakeholders. And, oh yeah, the code is freely available as well.

While OpenEco is targeted at organizations, feel free to add in your house or apartment. It will give you a sense of the tool and the power of the community. Hopefully it will help you understand your environmental impact, but more importantly, maybe it will spark an idea regarding something you know or have built and should be sharing with others.

We have begun to collect data relevant to environmental impact from a variety of sources. For example, we now know that more than 90% of Sun’s carbon footprint comes from energy use; and we are committed to openly sharing our energy consumption and related GHG emissions data and encourage other organizations to do the same.

Part II Summary, and What’s Next

This part of the book dealt exclusively with environmental responsibility—making products and services that meet societal, corporate, and/or personal goals for eco-effectiveness and sustainability. Those are key considerations for every engineer today, and there is enormous opportunity for engineering innovation in every aspect of eco responsibility and at every phase of the product or service lifecycle.

Yet, taken together, the environmental considerations represent just one aspect of being a true Citizen Engineer. Equally important is the way you innovate and use your ideas, and those of others, to create new products and services. The next part of the book is about the responsible use of ideas—how to share them, how to protect them, how to get others to amplify and propagate them—so that your innovations have maximum impact within your communities and companies, and in the marketplace.