12

COMPONENTS

Components are the units of deployment. They are the smallest entities that can be deployed as part of a system. In Java, they are jar files. In Ruby, they are gem files. In .Net, they are DLLs. In compiled languages, they are aggregations of binary files. In interpreted languages, they are aggregations of source files. In all languages, they are the granule of deployment.

Components can be linked together into a single executable. Or they can be aggregated together into a single archive, such as a .war file. Or they can be independently deployed as separate dynamically loaded plugins, such as.jar or .dll or .exe files. Regardless of how they are eventually deployed, well-designed components always retain the ability to be independently deployable and, therefore, independently developable.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF COMPONENTS

In the early years of software development, programmers controlled the memory location and layout of their programs. One of the first lines of code in a program would be the origin statement, which declared the address at which the program was to be loaded.

Consider the following simple PDP-8 program. It consists of a subroutine named GETSTR that inputs a string from the keyboard and saves it in a buffer. It also has a little unit test program to exercise GETSTR.

*200

TLS

START, CLA

TAD BUFR

JMS GETSTR

CLA

TAD BUFR

JMS PUTSTR

JMP START

BUFR, 3000

GETSTR, 0

DCA PTR

NXTCH, KSF

JMP -1

KRB

DCA I PTR

TAD I PTR

AND K177

ISZ PTR

TAD MCR

SZA

JMP NXTCH

K177, 177

MCR, -15

Note the *200 command at the start of this program. It tells the compiler to generate code that will be loaded at address 2008.

This kind of programming is a foreign concept for most programmers today. They rarely have to think about where a program is loaded in the memory of the computer. But in the early days, this was one of the first decisions a programmer needed to make. In those days, programs were not relocatable.

How did you access a library function in those olden days? The preceding code illustrates the approach used. Programmers included the source code of the library functions with their application code, and compiled them all as a single program.1 Libraries were kept in source, not in binary.

The problem with this approach was that, during this era, devices were slow and memory was expensive and, therefore, limited. Compilers needed to make several passes over the source code, but memory was too limited to keep all the source code resident. Consequently, the compiler had to read in the source code several times using the slow devices.

This took a long time—and the larger your function library, the longer the compiler took. Compiling a large program could take hours.

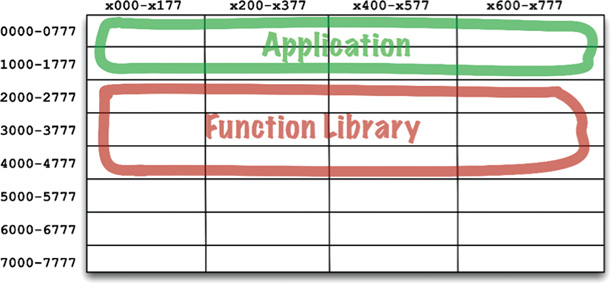

To shorten the compile times, programmers separated the source code of the function library from the applications. They compiled the function library separately and loaded the binary at a known address—say, 20008. They created a symbol table for the function library and compiled that with their application code. When they wanted to run an application, they would load the binary function library,2 and then load the application. Memory looked like the layout shown in Figure 12.1.

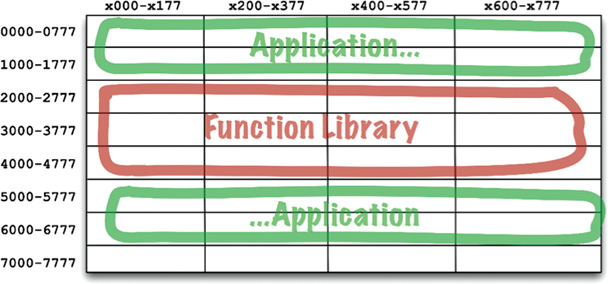

This worked fine so long as the application could fit between addresses 00008 and 17778. But soon applications grew to be larger than the space allotted for them. At that point, programmers had to split their applications into two address segments, jumping around the function library (Figure 12.2).

Obviously, this was not a sustainable situation. As programmers added more functions to the function library, it exceeded its bounds, and they had to allocate more space for it (in this example, near 70008). This fragmentation of programs and libraries necessarily continued as computer memory grew.

Clearly, something had to be done.

RELOCATABILITY

The solution was relocatable binaries. The idea behind them was very simple. The compiler was changed to output binary code that could be relocated in memory by a smart loader. The loader would be told where to load the relocatable code. The relocatable code was instrumented with flags that told the loader which parts of the loaded data had to be altered to be loaded at the selected address. Usually this just meant adding the starting address to any memory reference addresses in the binary.

Now the programmer could tell the loader where to load the function library, and where to load the application. In fact, the loader would accept several binary inputs and simply load them in memory one right after the other, relocating them as it loaded them. This allowed programmers to load only those functions that they needed.

The compiler was also changed to emit the names of the functions as metadata in the relocatable binary. If a program called a library function, the compiler would emit that name as an external reference. If a program defined a library function, the compiler would emit that name as an external definition. Then the loader could link the external references to the external definitions once it had determined where it had loaded those definitions.

And the linking loader was born.

LINKERS

The linking loader allowed programmers to divide their programs up onto separately compilable and loadable segments. This worked well when relatively small programs were being linked with relatively small libraries. However, in the late 1960s and early 1970s, programmers got more ambitious, and their programs got a lot bigger.

Eventually, the linking loaders were too slow to tolerate. Function libraries were stored on slow devices such a magnetic tape. Even the disks, back then, were quite slow. Using these relatively slow devices, the linking loaders had to read dozens, if not hundreds, of binary libraries to resolve the external references. As programs grew larger and larger, and more library functions accumulated in libraries, a linking loader could take more than an hour just to load the program.

Eventually, the loading and the linking were separated into two phases. Programmers took the slow part—the part that did that linking—and put it into a separate application called the linker. The output of the linker was a linked relocatable that a relocating loader could load very quickly. This allowed programmers to prepare an executable using the slow linker, but then they could load it quickly, at any time.

Then came the 1980s. Programmers were working in C or some other high-level language. As their ambitions grew, so did their programs. Programs that numbered hundreds of thousands of lines of code were not unusual.

Source modules were compiled from .c files into .o files, and then fed into the linker to create executable files that could be quickly loaded. Compiling each individual module was relatively fast, but compiling all the modules took a bit of time. The linker would then take even more time. Turnaround had again grown to an hour or more in many cases.

It seemed as if programmers were doomed to endlessly chase their tails. Throughout the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, all the changes made to speed up workflow were thwarted by programmers’ ambitions, and the size of the programs they wrote. They could not seem to escape from the hour-long turnaround times. Loading time remained fast, but compile-link times were the bottleneck.

We were, of course, experiencing Murphy’s law of program size:

Programs will grow to fill all available compile and link time.

But Murphy was not the only contender in town. Along came Moore,3 and in the late 1980s, the two battled it out. Moore won that battle. Disks started to shrink and got significantly faster. Computer memory started to get so ridiculously cheap that much of the data on disk could be cached in RAM. Computer clock rates increased from 1 MHz to 100 MHz.

By the mid-1990s, the time spent linking had begun to shrink faster than our ambitions could make programs grow. In many cases, link time decreased to a matter of seconds. For small jobs, the idea of a linking loader became feasible again.

This was the era of Active-X, shared libraries, and the beginnings of .jar files. Computers and devices had gotten so fast that we could, once again, do the linking at load time. We could link together several .jar files, or several shared libraries in a matter of seconds, and execute the resulting program. And so the component plugin architecture was born.

Today we routinely ship .jar files or DLLs or shared libraries as plugins to existing applications. If you want to create a mod to Minecraft, for example, you simply include your custom .jar files in a certain folder. If you want to plug Resharper into Visual Studio, you simply include the appropriate DLLs.

CONCLUSION

These dynamically linked files, which can be plugged together at runtime, are the software components of our architectures. It has taken 50 years, but we have arrived at a place where component plugin architecture can be the casual default as opposed to the herculean effort it once was.

1. My first employer kept several dozen decks of the subroutine library source code on a shelf. When you wrote a new program, you simply grabbed one of those decks and slapped it onto the end of your deck.

2. Actually, most of those old machines used core memory, which did not get erased when you powered the computer down. We often left the function library loaded for days at a time.

3. Moore’s law: Computer speed, memory, and density double every 18 months. This law held from the 1950s to 2000, but then, at least for clock rates, stopped cold.