25

LAYERS AND BOUNDARIES

It is easy to think of systems as being composed of three components: UI, business rules, and database. For some simple systems, this is sufficient. For most systems, though, the number of components is larger than that.

Consider, for example, a simple computer game. It is easy to imagine the three components. The UI handles all messages from the player to the game rules. The game rules store the state of the game in some kind of persistent data structure. But is that all there is?

HUNT THE WUMPUS

Let’s put some flesh on these bones. Let’s assume that the game is the venerable Hunt the Wumpus adventure game from 1972. This text-based game uses very simple commands like GO EAST and SHOOT WEST. The player enters a command, and the computer responds with what the player sees, smells, hears, and experiences. The player is hunting for a Wumpus in a system of caverns, and must avoid traps, pits, and other dangers lying in wait. If you are interested, the rules of the game are easy to find on the web.

Let’s assume that we’ll keep the text-based UI, but decouple it from the game rules so that our version can use different languages in different markets. The game rules will communicate with the UI component using a language-independent API, and the UI will translate the API into the appropriate human language.

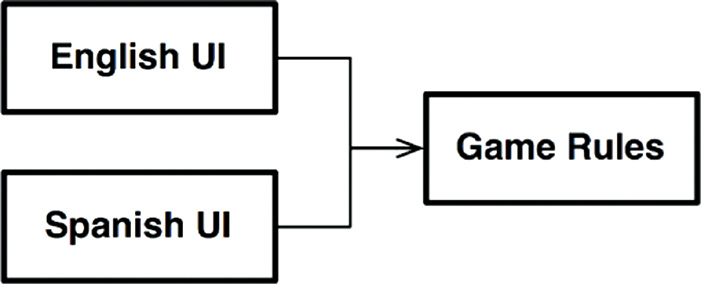

If the source code dependencies are properly managed, as shown in Figure 25.1, then any number of UI components can reuse the same game rules. The game rules do not know, nor do they care, which human language is being used.

Let’s also assume that the state of the game is maintained on some persistent store—perhaps in flash, or perhaps in the cloud, or maybe just in RAM. In any of those cases, we don’t want the game rules to know the details. So, again, we’ll create an API that the game rules can use to communicate with the data storage component.

We don’t want the game rules to know anything about the different kinds of data storage, so the dependencies have to be properly directed following the Dependency Rule, as shown in Figure 25.2.

CLEAN ARCHITECTURE?

It should be clear that we could easily apply the clean architecture approach in this context,1 with all the use cases, boundaries, entities, and corresponding data structures. But have we really found all the significant architectural boundaries?

For example, language is not the only axis of change for the UI. We also might want to vary the mechanism by which we communicate the text. For example, we might want to use a normal shell window, or text messages, or a chat application. There are many different possibilities.

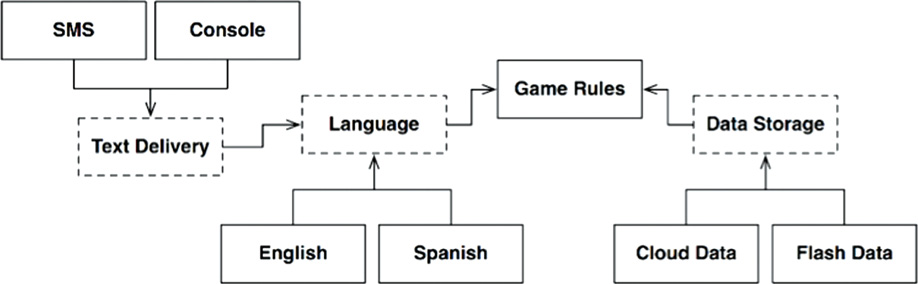

That means that there is a potential architectural boundary defined by this axis of change. Perhaps we should construct an API that crosses that boundary and isolates the language from the communications mechanism; that idea is illustrated in Figure 25.3.

The diagram in Figure 25.3 has gotten a little complicated, but should contain no surprises. The dashed outlines indicate abstract components that define an API that is implemented by the components above or below them. For example, the Language API is implemented by English and Spanish.

GameRules communicates with Language through an API that GameRules defines and Language implements. Language communicates with TextDelivery using an API that Language defines but TextDelivery implements. The API is defined and owned by the user, rather than by the implementer.

If we were to look inside GameRules, we would find polymorphic Boundary interfaces used by the code inside GameRules and implemented by the code inside the Language component. We would also find polymorphic Boundary interfaces used by Language and implemented by code inside GameRules.

If we were to look inside of Language, we would find the same thing: Polymorphic Boundary interfaces implemented by the code inside TextDelivery, and polymorphic Boundary interfaces used by TextDelivery and implemented by Language.

In each case, the API defined by those Boundary interfaces is owned by the upstream component.

The variations, such as English, SMS, and CloudData, are provided by polymorphic interfaces defined in the abstract API component, and implemented by the concrete components that serve them. For example, we would expect polymorphic interfaces defined in Language to be implemented by English and Spanish.

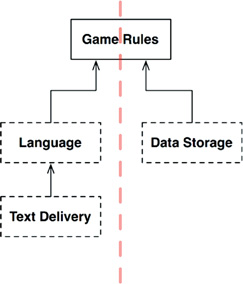

We can simplify this diagram by eliminating all the variations and focusing on just the API components. Figure 25.4 shows this diagram.

Notice that the diagram is oriented in Figure 25.4 so that all the arrows point up. This puts GameRules at the top. This orientation makes sense because GameRules is the component that contains the highest-level policies.

Consider the direction of information flow. All input comes from the user through the TextDelivery component at the bottom left. That information rises through the Language component, getting translated into commands to GameRules. GameRules processes the user input and sends appropriate data down to DataStorage at the lower right.

GameRules then sends output back down to Language, which translates the API back to the appropriate language and then delivers that language to the user through TextDelivery.

This organization effectively divides the flow of data into two streams.2 The stream on the left is concerned with communicating with the user, and the stream on the right is concerned with data persistence. Both streams meet at the top3 at GameRules, which is the ultimate processor of the data that goes through both streams.

CROSSING THE STREAMS

Are there always two data streams as in this example? No, not at all. Imagine that we would like to play Hunt the Wumpus on the net with multiple players. In this case, we would need a network component, like that shown in Figure 25.5. This organization divides the data flow into three streams, all controlled by the GameRules.

So, as systems become more complex, the component structure may split into many such streams.

SPLITTING THE STREAMS

At this point you may be thinking that all the streams eventually meet at the top in a single component. If only life were so simple! The reality, of course, is much more complex.

Consider the GameRules component for Hunt the Wumpus. Part of the game rules deal with the mechanics of the map. They know how the caverns are connected, and which objects are located in each cavern. They know how to move the player from cavern to cavern, and how to determine the events that the player must deal with.

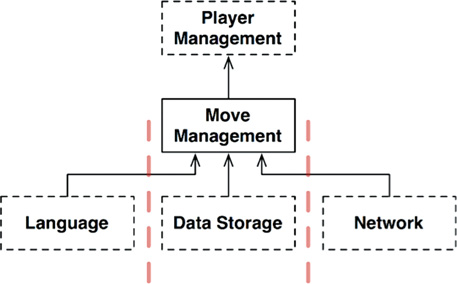

But there is another set of policies at an even higher level—policies that know the health of the player, and the cost or benefit of a particular event. These policies could cause the player to gradually lose health, or to gain health by discovering food. The lower-level mechanics policy would declare events to this higher-level policy, such as FoundFood or FellInPit. The higher-level policy would then manage the state of the player (as shown in Figure 25.6). Eventually that policy would decide whether the player wins or loses.

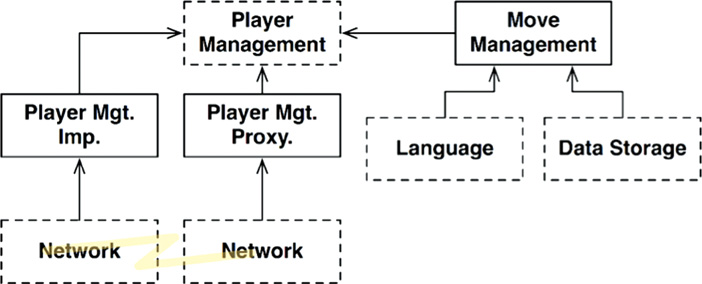

Is this an architectural boundary? Do we need an API that separates MoveManagement from PlayerManagement? Well, let’s make this a bit more interesting and add micro-services.

Let’s assume that we’ve got a massive multiplayer version of Hunt the Wumpus. MoveManagement is handled locally within the player’s computer, but PlayerManagement is handled by a server. PlayerManagement offers a micro-service API to all the connected MoveManagement components.

The diagram in Figure 25.7 depicts this scenario in a somewhat abbreviated fashion. The Network elements are a bit more complex than depicted—but you can probably still get the idea. A full-fledged architectural boundary exists between MoveManagement and PlayerManagement in this case.

CONCLUSION

What does all this mean? Why have I taken this absurdly simply program, which could be implemented in 200 lines of Kornshell, and extrapolated it out with all these crazy architectural boundaries?

This example is intended to show that architectural boundaries exist everywhere. We, as architects, must be careful to recognize when they are needed. We also have to be aware that such boundaries, when fully implemented, are expensive. At the same time, we have to recognize that when such boundaries are ignored, they are very expensive to add in later—even in the presence of comprehensive test-suites and refactoring discipline.

So what do we do, we architects? The answer is dissatisfying. On the one hand, some very smart people have told us, over the years, that we should not anticipate the need for abstraction. This is the philosophy of YAGNI: “You aren’t going to need it.” There is wisdom in this message, since over-engineering is often much worse than under-engineering. On the other hand, when you discover that you truly do need an architectural boundary where none exists, the costs and risks can be very high to add such a boundary.

So there you have it. O Software Architect, you must see the future. You must guess—intelligently. You must weigh the costs and determine where the architectural boundaries lie, and which should be fully implemented, and which should be partially implemented, and which should be ignored.

But this is not a one-time decision. You don’t simply decide at the start of a project which boundaries to implement and which to ignore. Rather, you watch. You pay attention as the system evolves. You note where boundaries may be required, and then carefully watch for the first inkling of friction because those boundaries don’t exist.

At that point, you weigh the costs of implementing those boundaries versus the cost of ignoring them—and you review that decision frequently. Your goal is to implement the boundaries right at the inflection point where the cost of implementing becomes less than the cost of ignoring.

1. It should be just as clear that we would not apply the clean architecture approach to something as trivial as this game. After all, the entire program can probably be written in 200 lines of code or less. In this case, we’re using a simple program as a proxy for a much larger system with significant architectural boundaries.

2. If you are confused by the direction of the arrows, remember that they point in the direction of source code dependencies, not in the direction of data flow.

3. In days long past, we would have called that top component the Central Transform. See Practical Guide to Structured Systems Design, 2nd ed., Meilir Page-Jones, 1988.