34

THE MISSING CHAPTER

By Simon Brown

All of the advice you’ve read so far will certainly help you design better software, composed of classes and components with well-defined boundaries, clear responsibilities, and controlled dependencies. But it turns out that the devil is in the implementation details, and it’s really easy to fall at the last hurdle if you don’t give that some thought, too.

Let’s imagine that we’re building an online book store, and one of the use cases we’ve been asked to implement is about customers being able to view the status of their orders. Although this is a Java example, the principles apply equally to other programming languages. Let’s put the Clean Architecture to one side for a moment and look at a number of approaches to design and code organization.

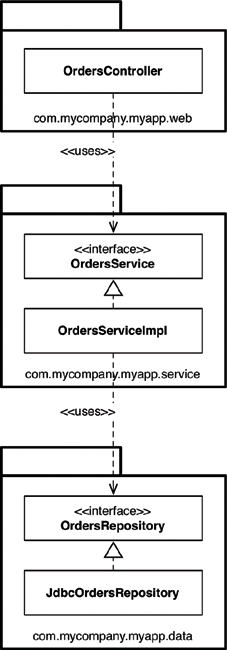

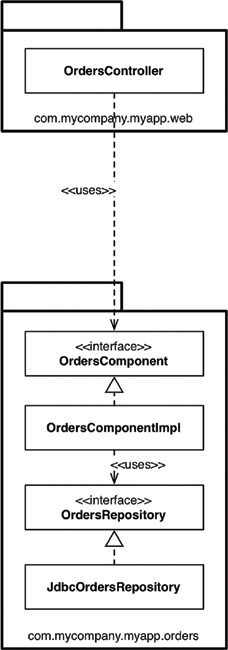

PACKAGE BY LAYER

The first, and perhaps simplest, design approach is the traditional horizontal layered architecture, where we separate our code based on what it does from a technical perspective. This is often called “package by layer.” Figure 34.1 shows what this might look like as a UML class diagram.

In this typical layered architecture, we have one layer for the web code, one layer for our “business logic,” and one layer for persistence. In other words, code is sliced horizontally into layers, which are used as a way to group similar types of things. In a “strict layered architecture,” layers should depend only on the next adjacent lower layer. In Java, layers are typically implemented as packages. As you can see in Figure 34.1, all of the dependencies between layers (packages) point downward. In this example, we have the following Java types:

• OrdersController: A web controller, something like a Spring MVC controller, that handles requests from the web.

• OrdersService: An interface that defines the “business logic” related to orders.

• OrdersServiceImpl: The implementation of the orders service.1

• OrdersRepository: An interface that defines how we get access to persistent order information.

• JdbcOrdersRepository: An implementation of the repository interface.

In “Presentation Domain Data Layering,”2 Martin Fowler says that adopting such a layered architecture is a good way to get started. He’s not alone. Many of the books, tutorials, training courses, and sample code you’ll find will also point you down the path of creating a layered architecture. It’s a very quick way to get something up and running without a huge amount of complexity. The problem, as Martin points out, is that once your software grows in scale and complexity, you will quickly find that having three large buckets of code isn’t sufficient, and you will need to think about modularizing further.

Another problem is that, as Uncle Bob has already said, a layered architecture doesn’t scream anything about the business domain. Put the code for two layered architectures, from two very different business domains, side by side and they will likely look eerily similar: web, services, and repositories. There’s also another huge problem with layered architectures, but we’ll get to that later.

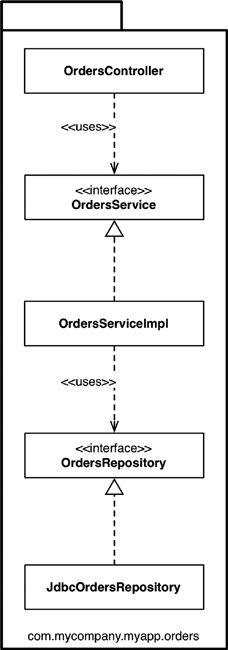

PACKAGE BY FEATURE

Another option for organizing your code is to adopt a “package by feature” style. This is a vertical slicing, based on related features, domain concepts, or aggregate roots (to use domain-driven design terminology). In the typical implementations that I’ve seen, all of the types are placed into a single Java package, which is named to reflect the concept that is being grouped.

With this approach, as shown in Figure 34.2, we have the same interfaces and classes as before, but they are all placed into a single Java package rather than being split among three packages. This is a very simple refactoring from the “package by layer” style, but the top-level organization of the code now screams something about the business domain. We can now see that this code base has something to do with orders rather than the web, services, and repositories. Another benefit is that it’s potentially easier to find all of the code that you need to modify in the event that the “view orders” use case changes. It’s all sitting in a single Java package rather than being spread out.3

I often see software development teams realize that they have problems with horizontal layering (“package by layer”) and switch to vertical layering (“package by feature”) instead. In my opinion, both are suboptimal. If you’ve read this book so far, you might be thinking that we can do much better—and you’re right.

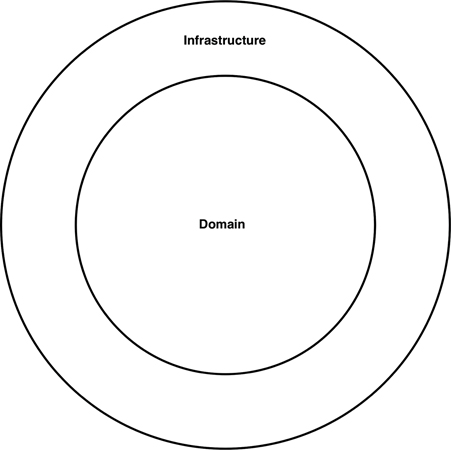

PORTS AND ADAPTERS

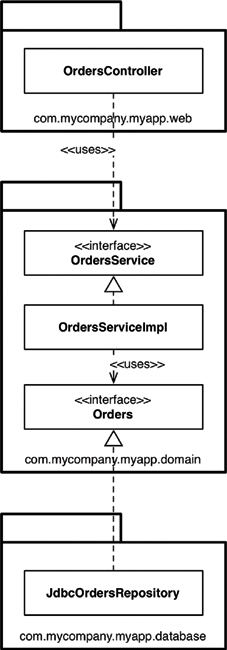

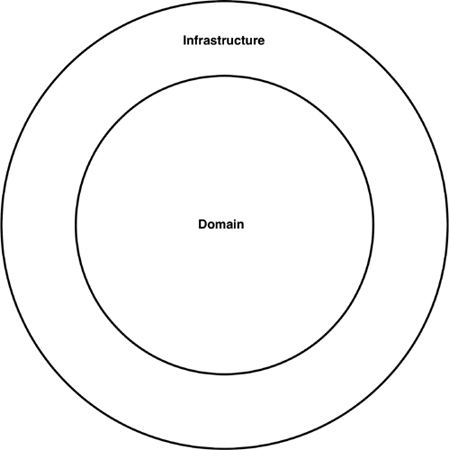

As Uncle Bob has said, approaches such as “ports and adapters,” the “hexagonal architecture,” “boundaries, controllers, entities,” and so on aim to create architectures where business/domain-focused code is independent and separate from the technical implementation details such as frameworks and databases. To summarize, you often see such code bases being composed of an “inside” (domain) and an “outside” (infrastructure), as suggested in Figure 34.3.

The “inside” region contains all of the domain concepts, whereas the “outside” region contains the interactions with the outside world (e.g., UIs, databases, third-party integrations). The major rule here is that the “outside” depends on the “inside”—never the other way around. Figure 34.4 shows a version of how the “view orders” use case might be implemented.

The com.mycompany.myapp.domain package here is the “inside,” and the other packages are the “outside.” Notice how the dependencies flow toward the “inside.” The keen-eyed reader will notice that the OrdersRepository from previous diagrams has been renamed to simply be Orders. This comes from the world of domain-driven design, where the advice is that the naming of everything on the “inside” should be stated in terms of the “ubiquitous domain language.” To put that another way, we talk about “orders” when we’re having a discussion about the domain, not the “orders repository.”

It’s also worth pointing out that this is a simplified version of what the UML class diagram might look like, because it’s missing things like interactors and objects to marshal the data across the dependency boundaries.

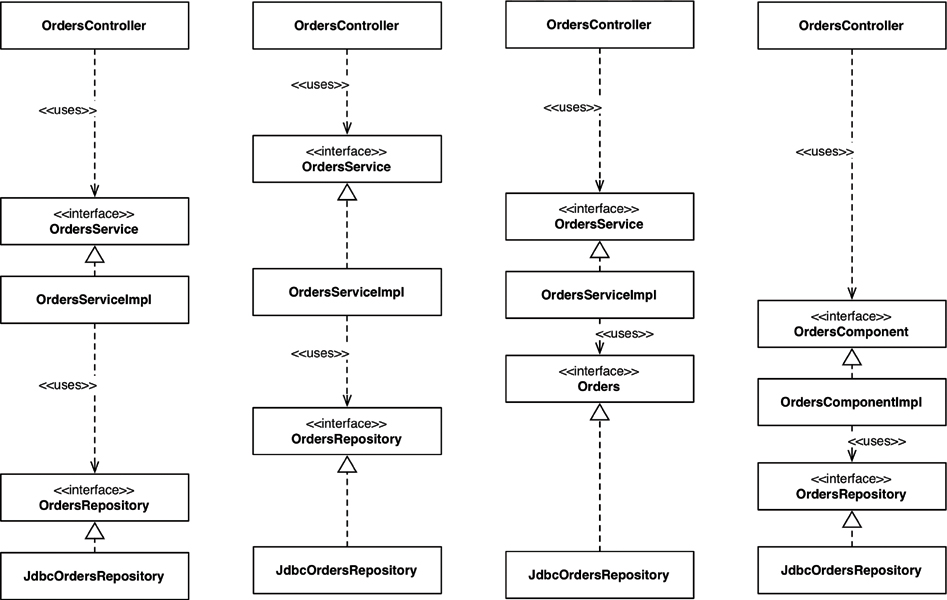

PACKAGE BY COMPONENT

Although I agree wholeheartedly with the discussions about SOLID, REP, CCP, and CRP and most of the advice in this book, I come to a slightly different conclusion about how to organize code. So I’m going to present another option here, which I call “package by component.” To give you some background, I’ve spent most of my career building enterprise software, primarily in Java, across a number of different business domains. Those software systems have varied immensely, too. A large number have been web-based, but others have been client–server4, distributed, message-based, or something else. Although the technologies differed, the common theme was that the architecture for most of these software systems was based on a traditional layered architecture.

I’ve already mentioned a couple of reasons why layered architectures should be considered bad, but that’s not the whole story. The purpose of a layered architecture is to separate code that has the same sort of function. Web stuff is separated from business logic, which is in turn separated from data access. As we saw from the UML class diagram, from an implementation perspective, a layer typically equates to a Java package. From a code accessibility perspective, for the OrdersController to be able to have a dependency on the OrdersService interface, the OrdersService interface needs to be marked as public, because they are in different packages. Likewise, the OrdersRepository interface needs to be marked as public so that it can be seen outside of the repository package, by the OrdersServiceImpl class.

In a strict layered architecture, the dependency arrows should always point downward, with layers depending only on the next adjacent lower layer. This comes back to creating a nice, clean, acyclic dependency graph, which is achieved by introducing some rules about how elements in a code base should depend on each other. The big problem here is that we can cheat by introducing some undesirable dependencies, yet still create a nice, acyclic dependency graph.

Suppose that you hire someone new who joins your team, and you give the newcomer another orders-related use case to implement. Since the person is new, he wants to make a big impression and get this use case implemented as quickly as possible. After sitting down with a cup of coffee for a few minutes, the newcomer discovers an existing OrdersController class, so he decides that’s where the code for the new orders-related web page should go. But it needs some orders data from the database. The newcomer has an epiphany: “Oh, there’s an OrdersRepository interface already built, too. I can simply dependency-inject the implementation into my controller. Perfect!” After a few more minutes of hacking, the web page is working. But the resulting UML diagram looks like Figure 34.5.

The dependency arrows still point downward, but the OrdersController is now additionally bypassing the OrdersService for some use cases. This organization is often called a relaxed layered architecture, as layers are allowed to skip around their adjacent neighbor(s). In some situations, this is the intended outcome—if you’re trying to follow the CQRS5 pattern, for example. In many other cases, bypassing the business logic layer is undesirable, especially if that business logic is responsible for ensuring authorized access to individual records, for example.

While the new use case works, it’s perhaps not implemented in the way that we were expecting. I see this happen a lot with teams that I visit as a consultant, and it’s usually revealed when teams start to visualize what their code base really looks like, often for the first time.

What we need here is a guideline—an architectural principle—that says something like, “Web controllers should never access repositories directly.” The question, of course, is enforcement. Many teams I’ve met simply say, “We enforce this principle through good discipline and code reviews, because we trust our developers.” This confidence is great to hear, but we all know what happens when budgets and deadlines start looming ever closer.

A far smaller number of teams tell me that they use static analysis tools (e.g., NDepend, Structure101, Checkstyle) to check and automatically enforce architecture violations at build time. You may have seen such rules yourself; they usually manifest themselves as regular expressions or wildcard strings that state “types in package **/web should not access types in **/data”; and they are executed after the compilation step.

This approach is a little crude, but it can do the trick, reporting violations of the architecture principles that you’ve defined as a team and (you hope) failing the build. The problem with both approaches is that they are fallible, and the feedback loop is longer than it should be. If left unchecked, this practice can turn a code base into a “big ball of mud.”6 I’d personally like to use the compiler to enforce my architecture if at all possible.

This brings us to the “package by component” option. It’s a hybrid approach to everything we’ve seen so far, with the goal of bundling all of the responsibilities related to a single coarse-grained component into a single Java package. It’s about taking a service-centric view of a software system, which is something we’re seeing with micro-service architectures as well. In the same way that ports and adapters treat the web as just another delivery mechanism, “package by component” keeps the user interface separate from these coarse-grained components. Figure 34.6 shows what the “view orders” use case might look like.

In essence, this approach bundles up the “business logic” and persistence code into a single thing, which I’m calling a “component.” Uncle Bob presented his definition of “component” earlier in the book, saying:

Components are the units of deployment. They are the smallest entities that can be deployed as part of a system. In Java, they are jar files.

My definition of a component is slightly different: “A grouping of related functionality behind a nice clean interface, which resides inside an execution environment like an application.” This definition comes from my “C4 software architecture model,”7 which is a simple hierarchical way to think about the static structures of a software system in terms of containers, components, and classes (or code). It says that a software system is made up of one or more containers (e.g., web applications, mobile apps, stand-alone applications, databases, file systems), each of which contains one or more components, which in turn are implemented by one or more classes (or code). Whether each component resides in a separate jar file is an orthogonal concern.

A key benefit of the “package by component” approach is that if you’re writing code that needs to do something with orders, there’s just one place to go—the OrdersComponent. Inside the component, the separation of concerns is still maintained, so the business logic is separate from data persistence, but that’s a component implementation detail that consumers don’t need to know about. This is akin to what you might end up with if you adopted a micro-services or Service-Oriented Architecture—a separate OrdersService that encapsulates everything related to handling orders. The key difference is the decoupling mode. You can think of well-defined components in a monolithic application as being a stepping stone to a micro-services architecture.

THE DEVIL IS IN THE IMPLEMENTATION DETAILS

On the face of it, the four approaches do all look like different ways to organize code and, therefore, could be considered different architectural styles. This perception starts to unravel very quickly if you get the implementation details wrong, though.

Something I see on a regular basis is an overly liberal use of the public access modifier in languages such as Java. It’s almost as if we, as developers, instinctively use the public keyword without thinking. It’s in our muscle memory. If you don’t believe me, take a look at the code samples for books, tutorials, and open source frameworks on GitHub. This tendency is apparent, regardless of which architectural style a code base is aiming to adopt—horizontal layers, vertical layers, ports and adapters, or something else. Marking all of your types as public means you’re not taking advantage of the facilities that your programming language provides with regard to encapsulation. In some cases, there’s literally nothing preventing somebody from writing some code to instantiate a concrete implementation class directly, violating the intended architecture style.

ORGANIZATION VERSUS ENCAPSULATION

Looking at this issue another way, if you make all types in your Java application public, the packages are simply an organization mechanism (a grouping, like folders), rather than being used for encapsulation. Since public types can be used from anywhere in a code base, you can effectively ignore the packages because they provide very little real value. The net result is that if you ignore the packages (because they don’t provide any means of encapsulation and hiding), it doesn’t really matter which architectural style you’re aspiring to create. If we look back at the example UML diagrams, the Java packages become an irrelevant detail if all of the types are marked as public. In essence, all four architectural approaches presented earlier in this chapter are exactly the same when we overuse this designation (Figure 34.7).

Take a close look at the arrows between each of the types in Figure 34.7: They’re all identical regardless of which architectural approach you’re trying to adopt. Conceptually the approaches are very different, but syntactically they are identical. Furthermore, you could argue that when you make all of the types public, what you really have are just four ways to describe a traditional horizontally layered architecture. This is a neat trick, and of course nobody would ever make all of their Java types public. Except when they do. And I’ve seen it.

The access modifiers in Java are not perfect,8 but ignoring them is just asking for trouble. The way Java types are placed into packages can actually make a huge difference to how accessible (or inaccessible) those types can be when Java’s access modifiers are applied appropriately. If I bring the packages back and mark (by graphically fading) those types where the access modifier can be made more restrictive, the picture becomes pretty interesting (Figure 34.8).

Moving from left to right, in the “package by layer” approach, the OrdersService and OrdersRepository interfaces need to be public, because they have inbound dependencies from classes outside of their defining package. In contrast, the implementation classes (OrdersServiceImpl and JdbcOrdersRepository) can be made more restrictive (package protected). Nobody needs to know about them; they are an implementation detail.

In the “package by feature” approach, the OrdersController provides the sole entry point into the package, so everything else can be made package protected. The big caveat here is that nothing else in the code base, outside of this package, can access information related to orders unless they go through the controller. This may or may not be desirable.

In the ports and adapters approach, the OrdersService and Orders interfaces have inbound dependencies from other packages, so they need to be made public. Again, the implementation classes can be made package protected and dependency injected at runtime.

Finally, in the “package by component” approach, the OrdersComponent interface has an inbound dependency from the controller, but everything else can be made package protected. The fewer public types you have, the smaller the number of potential dependencies. There’s now no way9 that code outside this package can use the OrdersRepository interface or implementation directly, so we can rely on the compiler to enforce this architectural principle. You can do the same thing in .NET with the internal keyword, although you would need to create a separate assembly for every component.

Just to be absolutely clear, what I’ve described here relates to a monolithic application, where all of the code resides in a single source code tree. If you are building such an application (and many people are), I would certainly encourage you to lean on the compiler to enforce your architectural principles, rather than relying on self-discipline and post-compilation tooling.

OTHER DECOUPLING MODES

In addition to the programming language you’re using, there are often other ways that you can decouple your source code dependencies. With Java, you have module frameworks like OSGi and the new Java 9 module system. With module systems, when used properly, you can make a distinction between types that are public and types that are published. For example, you could create an Orders module where all of the types are marked as public, but publish only a small subset of those types for external consumption. It’s been a long time coming, but I’m enthusiastic that the Java 9 module system will give us another tool to build better software, and spark people’s interest in design thinking once again.

Another option is to decouple your dependencies at the source code level, by splitting code across different source code trees. If we take the ports and adapters example, we could have three source code trees:

• The source code for the business and domain (i.e., everything that is independent of technology and framework choices): OrdersService, OrdersServiceImpl, and Orders

• The source code for the web: OrdersController

• The source code for the data persistence: JdbcOrdersRepository

The latter two source code trees have a compile-time dependency on the business and domain code, which itself doesn’t know anything about the web or the data persistence code. From an implementation perspective, you can do this by configuring separate modules or projects in your build tool (e.g., Maven, Gradle, MSBuild). Ideally you would repeat this pattern, having a separate source code tree for each and every component in your application. This is very much an idealistic solution, though, because there are real-world performance, complexity, and maintenance issues associated with breaking up your source code in this way.

A simpler approach that some people follow for their ports and adapters code is to have just two source code trees:

• Domain code (the “inside”)

• Infrastructure code (the “outside”)

This maps on nicely to the diagram (Figure 34.9) that many people use to summarize the ports and adapters architecture, and there is a compile-time dependency from the infrastructure to the domain.

This approach to organizing source code will also work, but be aware of the potential trade-off. It’s what I call the “Périphérique anti-pattern of ports and adapters.” The city of Paris, France, has a ring road called the Boulevard Périphérique, which allows you to circumnavigate Paris without entering the complexities of the city. Having all of your infrastructure code in a single source code tree means that it’s potentially possible for infrastructure code in one area of your application (e.g., a web controller) to directly call code in another area of your application (e.g., a database repository), without navigating through the domain. This is especially true if you’ve forgotten to apply appropriate access modifiers to that code.

CONCLUSION: THE MISSING ADVICE

The whole point of this chapter is to highlight that your best design intentions can be destroyed in a flash if you don’t consider the intricacies of the implementation strategy. Think about how to map your desired design on to code structures, how to organize that code, and which decoupling modes to apply during runtime and compile-time. Leave options open where applicable, but be pragmatic, and take into consideration the size of your team, their skill level, and the complexity of the solution in conjunction with your time and budgetary constraints. Also think about using your compiler to help you enforce your chosen architectural style, and watch out for coupling in other areas, such as data models. The devil is in the implementation details.

1. This is arguably a horrible way to name a class, but as we’ll see later, perhaps it doesn’t really matter.

2. https://martinfowler.com/bliki/PresentationDomainDataLayering.html.

3. This benefit is much less relevant with the navigation facilities of modern IDEs, but it seems there has been a renaissance moving back to lightweight text editors, for reasons I am clearly too old to understand.

4. My first job after graduating from university in 1996 was building client–server desktop applications with a technology called PowerBuilder, a super-productive 4GL that excelled at building database-driven applications. A couple of years later, I was building client–server applications with Java, where we had to build our own database connectivity (this was pre-JDBC) and our own GUI toolkits on top of AWT. That’s “progress“ for you!

5. In the Command Query Responsibility Segregation pattern, you have separate patterns for updating and reading data.

6. http://www.laputan.org/mud/

7. See https://www.structurizr.com/help/c4 for more information.

8. In Java, for example, although we tend to think of packages as being hierarchical, it’s not possible to create access restrictions based on a package and subpackage relationship. Any hierarchy that you create is in the name of those packages, and the directory structure on disk, only.

9. Unless you cheat and use Java’s reflection mechanism, but please don’t do that!