What do we need to know in our jobs and when do we need to know it?

What is the essential knowledge that makes us productive in our positions at WedgeMark?

What knowledge is critical, what knowledge is merely helpful, and what knowledge is tangential?

And, as one of the more eccentric members of our team put it, if you discovered that your house of knowledge was on fire, what knowledge would you choose to save?

These were the questions we asked each other as we wrestled with categorizing operational knowledge and developing a means to harvest and transfer it. They led us to the conclusion that the process of knowledge harvesting and transfer has three components:

A means for identifying critical operational knowledge and organizing it into knowledge categories

A methodology for harvesting the critical operational knowledge from incumbent employees

A "container" to store the critical operational knowledge and transfer it to the successor employee

We began with the container, which was the third component, because it described the knowledge categories that set the objectives for the knowledge harvest. Andre had already called it the knowledge profile.

The challenge of designing the profile was intriguing because none of us had ever systematically examined our operational knowledge needs. Some people intuitively understood those needs and some did not, but no one had ever tried to categorize them. In order to accomplish this task, we turned to our colleagues, casting a broad net in our effort to understand the meaning of job-critical operational knowledge. Over lunch, during breaks, at breakfast, through e-mail, and in informal focus groups, we asked people, "What is the critical knowledge you use on your job, and how would you categorize it?" Or, "If you had started your job, and your predecessor handed you a profile of the knowledge you needed for that job, what would that profile look like?"

From these conversations, we created the knowledge categories that defined critical operational knowledge at WedgeMark. We also developed a set of eight organizing principles to guide the design of the knowledge profile and determine its contents.

Principle 1: Knowledge profiles should contain only critical operational knowledge.

In the daily conduct of our jobs, we use a vast amount of operational knowledge. Most of it is easily acquired and of little real consequence, but some of it is critical to the work we do. It is the critical knowledge that the profile is designed to hold. If criticality is the criterion for including knowledge in the profile, then a definition is warranted. Unfortunately, a precise definition is not easy to frame. The effort to define critical for purposes of the profile is further complicated by two conflicting objectives of the profile design: conciseness and comprehensiveness. We wanted to keep the knowledge profile as short and easy to use as possible, but, at the same time, make it comprehensive enough to transfer the critical operational knowledge that successors needed.

We proposed three criteria for determining criticality: (1) knowledge that is essential to effective job performance, (2) high-impact knowledge that makes a significant difference in productivity or quality, and (3) knowledge that would have a big negative effect on performance if it were missing. In other words, we used phrases to define critical, understanding that they were hardly definitive, and left it up to the incumbents to determine criticality for the knowledge in their profile.

Sarah pointed out that the resulting knowledge profile would reflect the knowledge biases of the incumbents and the ways in which they had shaped their jobs to their own particular strengths.

"True enough," Andre agreed, "but that's inevitable."

There was another perspective, however, that proved reassuring. We concluded that some of the biases and individual differences would even out as knowledge profiles were built up over generations of employees. We also counted on meetings of peer incumbents to correct the most egregious errors or omissions in individual knowledge profiles, a process that is explained in more detail in Chapter 11 ("Creating the Knowledge Profile").

Principle 2: Incumbent employees require a structured means of identifying their critical operational knowledge.

Our interviews with colleagues at WedgeMark confirmed that incumbent employees cannot be relied on to identify critical operational knowledge for their positions without a structured means of analysis to assist them. There are four major reasons for this phenomenon:

Productive incumbents are so fluent in the operational knowledge they use—in the data, information, skills, knowledge, and competencies required to perform well—that their decisions and actions often seem instinctive. The knowledge and knowledge sources they use are so familiar to them that they make the false assumption that everyone else has the same knowledge. Because they take the knowledge for granted, they may fail to recognize it as critical or to identify it as knowledge someone else would need. Therefore, it can be difficult for productive incumbents to transfer what they know to their successors without a disciplined, systematic approach that provides a structured methodology for identifying and harvesting critical knowledge.

Incumbents may have difficulty drawing a distinction between critical knowledge, useful knowledge, and even irrelevant knowledge. As James Pollard, CEO of Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu, has pointed out, "What needs to be shared may not be as important as knowing what doesn't need to be shared" (Haapaniemi, 2001, p. 68).

Even if incumbents are aware of their critical operational knowledge, they generally do not know how to organize that knowledge in such a way that it can be efficiently and effectively transferred to their successors.

Many incumbents are not aware of the operational knowledge weaknesses that negatively affect their productivity and performance. These weaknesses, which take the form of missing, insufficient, inaccurate, or obsolete knowledge, reduce the utility of their operational knowledge, whether for them or their successors. The knowledge analysis built into the profile development process will identify these weaknesses.

Principle 3: The nature of employees' contractual arrangements affects their profiles.

Once upon a time, the word employee had a clear meaning. An employee was someone who worked full-time for a company in the company's offices or on the road selling the company's products. A person who worked part-time for the company was not spoken of as an employee, but as a part-time employee. Like so much else in the knowledge economy, even the meanings of employee and part-time employee have changed. Five types of potential employment arrangements are discernible in contemporary organizations, and each presents special knowledge continuity challenges that should be reflected in the contents of the knowledge profiles for those positions. But even these employment categories are not the whole picture, because they can be subdivided into full-time and part-time employees. The employment categories are shown in Table 8.1.

Part-time employees pose somewhat different knowledge challenges from full-time employees and constitute a special area of knowledge-loss exposure. Continuity management is valid for each employment category and for both full-time and part-time workers within those categories, but the knowledge profiles will be different for each.

Table 8.1. Employee Contractual Arrangements

Type | Full-Time | Part-Time | Description of Employment |

|---|---|---|---|

On-site | Physically goes to the office or the factory | ||

Telecommuter | Works at home or an outlying office | ||

Road warrior | Is in the office 4 or 5 days a month and otherwise on the road | ||

Loaned | Located at the facilities of a supplier, strategic partner, or customer | ||

Outsourced | Contractors, part-timers, consultants, and temporary and leased employees |

Principle 4: Knowledge profiles should reflect an analysis and prioritization of operational knowledge.

Because we wanted the knowledge profiles to benefit incumbents as well as successors, we built an analysis of operational knowledge into continuity management. The purpose of the analysis is threefold: (1) to prioritize operational knowledge, (2) to pinpoint knowledge holes, and (3) to identify knowledge leverage points, which consist of knowledge with exceptional potential to increase operational efficiency, effectiveness, and productivity. This inventorying process spotlights high-payoff knowledge areas that warrant attention. It also makes it possible for incumbents to find and discard obsolete knowledge or ignore tangential knowledge and focus on the acquisition, development, and application of knowledge that is critical to their productivity. This analytical process is described in Chapter 9 ("Developing K-PAQ: The Knowledge Profile Analysis Questions").

Principle 5: Knowledge Profiles should include an analysis of strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (SWOT).

Knowledge profiles should include an analysis of corporate strengths and weakness as well as opportunities and threats facing the organization and incumbents. This analysis provides a context for determining present and future action and is a critical component of operational knowledge. The SWOT analysis is described in Chapter 9 ("Developing K-PAQ: The Knowledge Profile Analysis Questions").

Principle 6. The criteria for requiring a knowledge profile should be the significance of the knowledge to the employee's job and the significance of the job to the success of the organization.

Which job classifications should have profiles? Two general criteria govern the choice: (1) how critical operational knowledge is to success in the job and (2) how critical the job is to the success of the organization. In practice, these criteria are hard to measure, because critical is difficult to define.

"It's a matter of context," Sarah said. "It's looking at the big picture and asking if it's worth creating a knowledge profile for that position. It's all subjective, it seems to me."

"Not entirely," Andre countered. "In fact, the knowledge continuity assessment gives us a very good picture of knowledge discontinuities and the positions where they occur most frequently and with the greatest consequences for WedgeMark."

"In the final analysis, we may have to leave it up to each manager to determine," Cheryl suggested.

"Maybe," Andre replied. "But the one thing we do know from the knowledge continuity assessment is to err on the side of caution. Knowledge loss through departing employees is more costly than we have realized or been willing to acknowledge."

Our reexamination of the knowledge continuity assessment led us to this conclusion: Virtually all the employees at WedgeMark had knowledge that was critical to their positions, but the impact of knowledge loss would be considerably greater on some positions than on others (obviously). We decided that the critical operational knowledge in all these positions was ultimately important to WedgeMark if we were to build a high-performing organization in the knowledge economy. In some cases, the operational knowledge was not complex, and the depth of knowledge would not be great, but the knowledge itself was worth preserving and transferring.

Did that mean that it was knowledge profiles for everyone? Not necessarily, but perhaps for the vast majority of employees. After all, the complexity of preparing the knowledge profile generally parallels the complexity of the job. Less complicated positions require less complicated profiles. And some knowledge continuity is better than no knowledge continuity. We ended our discussion by agreeing with Andre's conclusion: It was better to err on the side of caution. A knowledge profile, however reduced in scope compared to those for more complicated positions, was still important to new hires with a knowledge aspect to their jobs. It still reduced their ramp-up time, increased their productivity, and made them feel like valuable members of the WedgeMark team, which they are.

Principle 7. Knowledge profiles should be easy to understand and access and should be meaningful to both incumbents and successors.

Obvious, but important. The content of the knowledge profile should be organized in a format that is meaningful to incumbents who prepare the profile and to successors who receive it. Profile content should be current, easy to understand, and simple to use—an interactive resource rather than a file somewhere in storage.

Principle 8. Access to portions of the knowledge profile should be restricted.

We found early on that we would have to confront a touchy issue regarding the knowledge profiles: Who would have access to them? Only the incumbent? An incumbent's boss? An incumbent's boss's boss? Someone from HR? A fear of putting some operational knowledge into the written word surfaced early.

"I might—might—be willing to tell someone certain things about past failures at the company, about the incompetence of some of our suppliers, and dumb moves by witless managers, but I'm sure not going to put it in writing," was an early response from a member of the focus groups.

Another person said, "If I thought just anybody could look at my profile, I might put some neutral stuff in there, but wouldn't put down anything private."

"It depends on whether I have to. If I have to—you know, if my evaluation depends on it—I guess I would, but I wouldn't want to unless two things were true. First, everybody else was doing it, and second, people needed my permission to look at my profile."

"This is a serious issue," confirmed a long-time employee. "Who's going to monitor these profiles to be sure we're doing them? And what are they going to do when they read some of the things in there?"

Access to the knowledge profile raised other concerns in the focus groups, most of them centering around creating new conflicts or resurrecting old ones, exposing untouchable topics, inflaming highly emotional issues that simmered just below the surface, or exposing errors in judgment that could jeopardize an incumbent's career (or someone else's). Other concerns rose from misguided loyalty to customers, suppliers, or bosses that prevented an accurate assessment of their performance—an assessment that might seem foolish or be held against them.

These concerns led us to a sustained discussion on the issue of who should be permitted to access a knowledge profile. Unfortunately, we were not able to completely resolve the question. Many different perspectives and opinions emerged, and we were unable to reach consensus until much later, when we resolved the issue in larger forums and in a way that was right for WedgeMark. Our own solution might not work for your organization, but it worked for us because it fit our culture, mission, goals, and traditions. From the standpoint of reporting our discussions and the decisions we made, perhaps the most effective approach is to summarize the areas in which the members of KC Prime agreed and disagreed.

The central question we asked ourselves was: Who but the incumbent should have access to a knowledge profile? The answer to that question seemed to depend largely on the job classification of the person providing it. The HR people had one set of views, the attorneys for the company another, and the incumbents themselves a third—although, ironically, the HR people and the attorneys were also incumbents, so they took a sometimes schizophrenic approach to the question. Furthermore, not all the incumbents agreed—and, as might be expected, some incumbents thought they should have more access to the profiles of their subordinates than they thought their supervisors should have to theirs.

We approached the issue by sorting though the access options. Who were the people who might have a claim on some portion of an incumbent's knowledge profile? Our answers were:

The incumbent

Peers of the incumbent

Subordinates of the incumbent

The direct supervisor of the incumbent

Higher-level supervisors

Managers (if not the higher-level supervisor)

Vice presidents (if not the higher-level supervisor)

HR representatives

Corporate attorneys (on demand)

Successors and those who would work with incumbents in assimilating the knowledge in the profile

Other WedgeMark employees for whom some of the operational knowledge in the Profile might prove useful

The only category we could agree on as having a right to access the entire knowledge profile was the first—the incumbent. On the other hand, almost everyone agreed that peer incumbents should not automatically have complete access to any knowledge profile other than their own. The reasoning was uniform: The profile would likely contain confidential information that we might be willing to transfer to our successors but not to some of our peers, with whom, frankly, we might be competing for future promotions. (This conclusion was an early indicator that the organizational rewards and culture at WedgeMark were not amenable to knowledge sharing and would have to be addressed.)

As we thought through our positions, however, and learned to listen more closely to what those with opposing views were saying, we began to see larger possibilities. We had the first glimmer, for example, that the knowledge profile could be linked to, or even integrated with, knowledge management databases and that real synergy might result. Our network of contacts, for example, or our sources of expert advice could benefit many people. As we became more collaborative in our thinking, we began to see that there might be advantages to having supervisors access our profiles. By providing a concise summary of our work experience, skill sets, and past projects, the profiles could be an important tool in making assignments. The more we thought about it, the more we realized that the operational knowledge in our profiles was, to a large extent, common knowledge that could be shared with incumbents and others and that it could, in fact, be enhanced by that sharing.

We recognized, for example, that the contents of the profiles revealed significant information about job-related skills and activities that could be of use to HR in recruitment, selection, and training and, especially, in developing continuous learning opportunities that would enhance our existing skills or teach us new ones. HR access could be positive rather than just regulatory. The profiles could also be helpful to others who might be recruiting members of a team in which we had an interest. Over time, we came to see that sharing the profiles and parts of the operational knowledge they contained could work to our advantage.

However, we all had a proprietary feeling about our knowledge profiles. It wasn't so much that we wanted to keep them secret as that they felt very personal to us, and they had to be managed with those feelings in mind. Our profiles might be our legacy to a successor or they might just represent our best thinking, but they still were our stuff, and we didn't want just anyone messing with them or looking in on them without our permission. We had all regressed, perhaps, but we felt that the profiles should be fundamentally private, with certain parts accessible to others who had a need to know. The question was how broad that need to know should be. We did agree that corporate attorneys should have access to the profiles and that HR should under certain circumstances, because we knew it was hopeless to think that any organization would allow mystery comments to float around without any check on them, especially when such mystery comments were contained in official corporate documents.

In the final analysis, we decided that there should be no access to any knowledge profile without the permission of the person who had created it or else an established purpose for the look. It was possible for the creator of a profile to offer blanket access permission or, alternatively, to restrict access to some or all of the profile during his or her tenure at WedgeMark. Blocking total access, however, would be discouraged. Toward that end, we recommended three security levels for the knowledge categories and subcategories contained in the Profiles. These designations were simple:

Available. Knowledge that was accessible to any WedgeMark employee authorized to access a knowledge profile.

Restricted. Knowledge that was restricted to peers, designated peers, or others of the profile creator's choosing.

Confidential. Knowledge that was unavailable except to individuals with a need to know, such as corporate attorneys on demand, HR people with good reasons to view the profiles, and our direct supervisors as part of our performance evaluations.

As we thought through access to the knowledge profiles, the risks did not seem as great as they had at first, and they were considerably outweighed by the potential benefits. Meetings of peer incumbents that facilitated cross-sharing of operational knowledge among peers had vetted much of the knowledge in the profiles (described in more detail in Chapter 11, "Creating the Knowledge Profile"). And most of the knowledge in the profile wasn't particularly personal. What we finally realized was that we had to design the profile and the context in which it was created, transferred, and applied so that it would be a respected creation perceived as adding value to the organization. We wanted people to have a sense of pride and accomplishment in their profiles.

Does that mean that we were completely honest about what we put in the knowledge profiles? The answer to that question is yes and no. Yes, we were honest in what we inserted. Based on conversations in peer incumbent meetings, our communities of practice, and informal gatherings, we determined that most of us had been truthful in what we had revealed, and each of us had revealed a lot. Did that mean that we had revealed everything? No, it did not. But once the profile creation process was over, we could see that few of us had intentionally withheld very much and that what we had created was immensely valuable to ourselves and to our successors. The profiles might not have been absolutely complete, but they were very accurate, and so much more complete than anything we had ever had before.

We also addressed the potential for intentional dishonesty that would skew operational knowledge in one direction or another for political purposes or to advance private agendas. How was the knowledge profile to be protected from dishonest incumbents with grudges or from disgruntled incumbents about to leave and bent on sabotage? The dishonest incumbents were difficult to defend against, but not impossible. Direct supervisors offered some oversight protection in performance evaluations. Also, the individual assigned to help the successor to assimilate the operational knowledge in the profile would afford additional protection. For the most part, we simply banked on there not being too many such incumbents.

Disgruntled incumbents who might sabotage their profile by destroying its contents or altering the data prior to their departure would be foiled by regular backup profiles stored outside of their reach and retained for a period of 18 months. These measures were some of those we developed to preserve the integrity of the knowledge profile, but we were confident that more would emerge as we began to implement continuity management at WedgeMark.

These principles for developing the knowledge profile were captured by Roger for the take-aways with which he was now identified:

With the principles to guide us, we turned to the task of creating the content of the knowledge profile. As a summary of the knowledge assets that an employee deploys in his or her job, the profile was intended to capture all types of knowledge, including cognitive knowledge (content knowledge), skills knowledge (know-how), systems knowledge, social network knowledge, process and procedural knowledge, heuristic knowledge, and cultural knowledge (discussed in Chapter 2, "Knowledge as a Capital Asset"). This long list of operational knowledge types would have been dismaying had it not been for "the Chip," our team member who calmly reminded us, "It's simple." But then, her logical mind found many things simple, for which she had earned the other sobriquet, "Mr. Spock's niece."

The many sessions that led to the final format of the knowledge profile were immensely rewarding for all of us. We brainstormed, analyzed, debated, argued, got huffy, laughed, and kept working. We used artistic metaphors like sculpting, modeling, and crafting to describe the work that led to the design and redesign of the prototype profile. As we continued to refine the profile, we took it to others and endured their criticisms even as we listened intently and altered our work in response to their insightful comments.

When we finally examined the finished product, laid out before us on a single page, we liked what we saw.

"A rhapsody of words," our Shakespeare-quoting team member proclaimed.

"Nice detail," Roger declared.

"It does organize the operational knowledge required for any job in the company as we intended," the Chip confirmed.

As we designed it, the profile gives both incumbents and successors extraordinary access to the critical operational knowledge they need, an overview of the resources at their disposal, and a snapshot of priorities that range from urgent items to long-term goals. The profile identifies critical knowledge, knowledge leverage points, and knowledge holes. It is comprehensive in scope, yet it can drill down to many levels of detail.

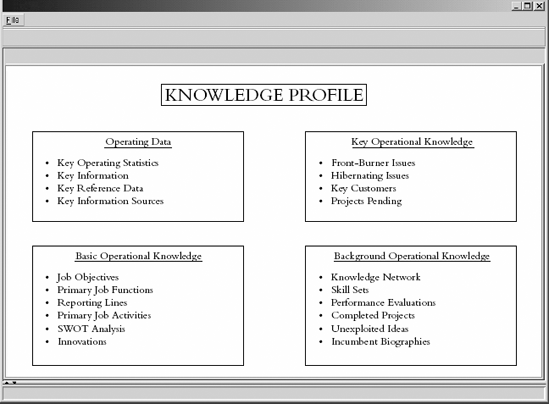

The knowledge profile groups critical operational knowledge into four knowledge sections: Operating Data, Key Operational Knowledge, Basic Operational Knowledge, and Background Operational Knowledge. These four sections contain a total of 20 knowledge categories, shown in Figure 8.1 as a portal on a computer screen. The knowledge category is the basic structural unit of the profile. Each knowledge category contains multiple knowledge topics related to that category. The design of the profile is thus:

Each knowledge category can be clicked to display the knowledge topics it contains and expanded again to show content details.

To personalize the knowledge profile and make its transfer from incumbent to successor as effective as possible, we added a special feature to the profile introduction. The introduction explains the purpose of the profile, defines its knowledge categories, and provides a set of recommended guidelines for its use. The special feature is a personal note from the last incumbent who owned the profile—that is, the new hire's predecessor. This note takes the form of a supportive message acknowledging that there is a lot to learn about the job, but expressing confidence in the successor's ability to acquire the knowledge and to succeed. The actual wording is determined by the incumbent and can be as long or as short as desired. There are no rules about format, content, or writing style. The note is what it claims to be: a personal message from the incumbent to the successor. Some incumbents have added a contact e-mail address. Incumbents who have been transferred to another part of WedgeMark are the most likely candidates for this addition, but a surprising number of others offer to be contacted, at least for a period of time and under certain circumstances. Other incumbents simply end the note with a general expression of good wishes and good luck.

When a new incumbent takes over the profile, the note from the last incumbent passes into the Incumbent Biographies knowledge category along with the biography of the person who wrote it, providing an archived history of personal notes as well as biographies. Our objective with this introduction was to keep the profile as personal, friendly, and welcoming as possible. We wanted the new hire to start out with a sense of being valued and with a sense that the knowledge profile was something important—a true legacy to which the new hire was heir as a WedgeMark employee.

The knowledge profile is structured around 20 knowledge categories grouped into four knowledge sections. One of the major contributions of the profile is this categorization of critical operational knowledge, which gave us a handle on how to capture, organize, and transfer that knowledge. When the profile is created with sophisticated technology, all its knowledge is accessible through questions and key word searches. Its knowledge can also be accessed directly through the knowledge categories. While employees do not generally like to search databases for knowledge, our experience has been that new hires willingly access their knowledge profiles because their job-specific operational knowledge is virtually zero. When they can search in the form of frequently asked questions, which the WedgeMark continuity management system offers, the task is that much easier.

We created a knowledge profile template for all of WedgeMark, which was meant to be universal. Most of the knowledge categories would remain valid across WedgeMark, but not all of them would. Accounting, engineering, sales, budgeting, planning, research and development, production, and marketing might have significant differences within the knowledge categories for their positions. Our aim was to create a model profile that would allow individual customization by job classification. That necessarily meant that the model profile might include more knowledge categories than necessary for every job classification and, in some cases, fewer than might be necessary.

The following paragraphs describe the contents of each of the knowledge sections and the knowledge categories of the profile. Even the topics within the knowledge categories, however, are subject to change based on the job classification. Some classifications will require more knowledge topics and some will require fewer topics to match the profile to the job. The profile we prepared for WedgeMark was a model designed to stimulate thinking within each unit about that unit's operational knowledge and how the profile's contents should be altered to fit it precisely.

Operating Data contains current, routinely used operating data, basic reference data, and the results of financial and other analyses that provide specialized information for controlling, monitoring, or decision making. The knowledge categories in Operating Data are:

Key Operating Statistics. Key operating statistics that are critical to the job classification (for example, monthly sales figures, sales trends, market share, budgets, cash flow projections, and so forth).

Key Information. Official corporate announcements, late-breaking news, personnel changes, and other current information about which the employee needs to be aware.

Key Reference Data. This knowledge category is divided into two subcategories. The first includes personal reference data such as telephone numbers, forthcoming events, number of vacation days used, looming deadlines, and so forth. The second subcategory includes job-relevant corporate reference data such as policies and procedures manuals, market and competitor analyses, product plans, pricing sheets, service guides, user manuals, and so forth.

Key Information Sources. The sources through which the data and information in this section of the knowledge profile can be obtained, whether documents or individuals.

Key Operational Knowledge contains knowledge related to current issues, customers, and projects that is crucial for successors to know. Such knowledge is often tacit rather than explicit. The knowledge categories in Key Operational Knowledge are:

Front-Burner Issues. Front-burner issues include major decisions, assignments, questions, tasks, controversies, opportunities, threats, or anything else that may require quick action with potentially serious consequences.

Hibernating Issues. Hibernating issues are ongoing threats, opportunities, controversies, events or other issues that carry particular risk or reward, but that are currently dormant. The incumbent must either continually monitor them or else be knowledgeable enough about them to respond quickly should they suddenly erupt.

Key Customers. This knowledge category includes all of an incumbent's most important customers (those to whom goods and services are provided), whether inside the organization (internal customers) or outside the organization (external customers), including their contacts, history, special needs, requirements, expectations, and other relevant information.

Projects Pending. This category includes any project in which the incumbent is involved that could have a significant impact on the organization. As pending projects are closed, they are archived and stored for future reference under Completed Projects, a knowledge category in the Background Operational Knowledge section of the profile.

Basic Operational Knowledge contains foundational knowledge that describes the parameters of the job. It is found in mission statements, annual goals, budgets, databases, organizational charts, Web pages, policies, procedures, memos, strategic analyses, and other official documents. But it is the kind of knowledge that also grows out of on-the-job experience, arises from stories passed among colleagues, and develops from thoughtful analysis. The knowledge categories in Basic Operational Knowledge are:

Job Objectives. This category includes organizational and unit mission statements, general goals and objectives of the unit, performance goals and objectives for the coming year, and other personalized short- and long-term goals and objectives expressed in performance measurements.

Primary Job Functions. This category includes the major functions of the job classification in their approximate order of importance, the amount of time usually devoted to each function, and a list of functions that waste time, drain resources, or otherwise fail to support performance objectives.

Reporting Lines. This category includes formal reporting lines depicted in the organizational chart, informal reporting lines, and an analysis of the reporting preferences of each person.

Primary Job Activities. This category includes the primary job activities (whether tasks or responsibilities) that are conducted regularly or periodically in support of the job's functions and objectives, the amount of time devoted to each, the knowledge required for each, and the related processes.

SWOT Analysis. SWOT analysis is an analysis of the organization's internal strengths and weaknesses (including competitive advantages), and an analysis of threats and opportunities facing the organization or the incumbent.

Innovations. This is the knowledge category that captures shortcuts, better ideas, innovations, or changes in established procedures or services that the incumbent has developed, heard about, or otherwise put to use in a productive way. These are often informal, unofficial procedures or processes that are part of the incumbent's tacit knowledge base and that represent significant opportunities for increased productivity or effectiveness. Or they may be whole new processes or services that can be immediately adapted by the successor (and spread through knowledge management best practices).

The potential contribution of the Innovations knowledge category is very high. That this category will fulfill its purpose is supported, at least conceptually, by a program initiated at Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu, the professional services company. James Copeland, CEO, describes that program:

One of the ways we've tried to capture and leverage knowledge is to find and create new ideas for services through what we call a venture board. This is an internal organization. We wanted to offer new, valuable services to the marketplace, and we figured that's best found in the minds of our people. So we told people to send in their ideas. And, of course, the response was less than overwhelming. So what we found we had to do was go out into the offices, convene meetings, and ask, "What are you doing that's smart for your clients?" We found a veritable gold mind of ideas—value that had already been created for clients. We knew those ideas worked, and there's no reason we couldn't use them for a thousand of our clients instead of just two of our clients. (Haapaniemi, 2001, p. 67)

Background Operational Knowledge contains knowledge that incumbents may not consciously use every day but is essential to their operational knowledge. The knowledge categories in Background Operational Knowledge are:

Knowledge Network. This category contains the names of the people inside and outside the organization who comprise the incumbent's knowledge network. It consists of colleagues, mentors, previous bosses, old friends, suppliers, superiors, and others on whom the incumbent relies for information, knowledge, and advice.

Skill Sets. This category describes the skills required to function well in the job.

Performance Evaluations. This category describes the process by which employee performance is evaluated, compensation is set, and promotions are earned, whether formally disclosed or not.

Completed Projects. This category contains the historical record of all major projects completed by incumbents during their tenure with the organization. It is automatically populated from the Projects Pending category in the Key Operational Knowledge section of the profile when incumbents classify their pending projects as complete and closed.

Unexploited Ideas. This category includes innovative solutions, creative ideas, and imaginative approaches developed by incumbents as they manage the requirements of their jobs, but not yet implemented. It is the tickler file for future action and a memo pad for ideas, notions, and brainstorms.

Incumbent Biographies. This category includes a photograph and biography of every incumbent who has contributed to the knowledge profile, beginning with the founding incumbent, who is the profile's originator. As successors become incumbents, they add their own photographs and biographies to create a personal, visual record of all those who have contributed to the knowledge profile they now possess. Biographical sketches include whatever professional achievements the incumbents select and, to the extent the incumbents are willing, personal data to personalize the profiles. These biographies personalize the process of knowledge profile construction, create a sense of ownership of the knowledge profile, act as an incentive for making the profile as complete as possible, and build identification and trust between incumbents and their successors.

With completion of the knowledge profile, the next challenge was to figure out the major topics to be covered in each of the knowledge categories and the questions that would fill those categories with critical operational knowledge from the minds of incumbents. That task was assigned to the Dream Team.