“Personality is the mysterious force that attracts us to certain people and repels us from others. Because personality greatly influences our decision-making process, it can be a powerful tool in design.”

—Aarron Walter, Designing For Emotion

Charlie Kaufman’s Anomalisa employs creepily realistic stop-motion puppetry to tell the story of Michael Stone, a customer service expert attending a conference in Cincinnati. With one exception, every person Michael encounters—hotel staff, conference attendees, airplane passengers—makes monotonous chitchat in an identical voice. This is conversation bereft of personality. A world of undifferentiated interaction closes in.

In life, every one of us manages to have a unique personality without even thinking about it. But imbuing a service with a personality requires a lot of thought. Creating and sustaining an appropriate and effective human voice within an interface requires effort and intention. It’s all too easy to neglect sociability and let the machine do the talking, or overwork your words into chipper clichés.

Because of this, the public voices of so many organizations sound the same, even when they’re talking about very different things. It might make sense to avoid being too idiosyncratic if you’re trying to reach the broadest possible audience. But if you’re truly offering something of unique value to the world, the way you talk about it should have a distinct quality, right?

Otherwise your customers will find themselves trying to navigate a mid-level netherworld where everything sounds like the same pair of beige slacks. And no one wants that.

You’ve Got Personality

A personality is the consistent set of human characteristics embodied by your product, service, or organization. While a brand is the sum of all the associations in the mind of your customer, the personality is how the system is designed to sound and behave. Voice and personality are often used as synonyms, but even a wordless interactive system may have a personality, as long as it displays or elicits emotions that are sufficiently human. (That a text can “say” something important, and one author may “sound” like another in writing, shows how easily we’ve been mentally switching modes all along. Now that more of our devices are speaking aloud, it’s probably better to reserve “voice” in practice for the audible aspects of an interface.)

In addition to a brand and personality, some companies also create a character. A character is a named entity apart from your organization or brand name that takes the personification a bit further and represents some or all of the brand attributes or characteristics. Organizations sometimes use characters as mascots to add playfulness and increase recognition. For example, MailChimp has a cartoon chimp named Freddie who functions as a simian emoticon. Freddie smiles and winks, but never speaks.

Anthropomorphizing is a thing people do. We see faces in electrical outlets and talk to our plants. So, if you don’t craft a personality intentionally, one will be assigned by your customers, in their minds. And it won’t be as good and the one you create and control.

One of the most effective and delightful personalities belongs to Slack. I’ll let Anna Pickard, the editorial director, explain:

There’s a sense of recognition, the same simple, straightforward language that helps you in the onboarding process is the one that carries you through every interaction. It is sometimes funny, sometimes serious, sometimes just plain and informative, but throughout, it should feel like nothing more than a person, talking to another person. Human to human.

The voice and design are woven tightly together. The bright colours of the logo and playfulness of animations match the tone of the copy in the product and all around it. The tone was set early on – it’s very much in the voice of Stewart Butterfield (and the other founders) and my work has been in learning how to scale and expand this without losing the sense that you were talking to a friendly co-worker. (http://bkaprt.com/cd/04-01/)

The fewer senses your service engages, the more work falls to the voice. Chatbots, the text-based agents that populate messaging systems, are nothing without their personalities. As Ben Brown, cofounder of botmaker Howdy, said:

It’s nearly the ultimate challenge for digital design, because in most cases, you don’t have control of what it looks like at all. How can you boil your entire app experience down into two lines of text? There’s nothing else on the screen but that. (http://bkaprt.com/cd/04-02/)

If your product communicates with a voice UI, not only does personality carry the weight of the product design, you’ll need to assign a gender (or offer a selection), as well. This introduces a whole range of considerations and opportunities. Customers may either make an emotional connection, or be repelled based on their associations between a system’s capabilities and its gender presentation.

Both Amazon and Google offer voice-activated talking speakers (Amazon Echo and Google Home respectively) for use as home assistants. Amazon named theirs Alexa, while Google refrained from creating a separate named personality. As Google’s Scott Huffman put it, they “shied away from the idea of kind of a human persona for search or for the entity that you’re interacting with and instead tried to go for, in some sense, ‘hey, you’re interacting with all of Google.’”

The implications of this choice prompted the designer Johna Paolino to write a Medium post reflecting on how it affected her:

Amazon is the name of a pioneering e-commerce platform and revolutionary cloud computing company. Echo is its product name, first to market of its kind. Alexa? Alexa is just the name of a female that performs personal tasks for you in your home.

Apple & Siri set a precedent for this. Was there a need to rename the voice component of these products? Why isn’t it Echo or Amazon? Why not Apple? By doing this, we’ve subconsciously constrained the capabilities of a female. With the Echo, we’ve even gone as far as to confine her to a home.

The voice component of the Google Home however is simply triggered with “Google”. Google, a multinational, first-of-its-kind technology company. Suddenly a female’s voice represents a lot more. This made me happy. (http://bkaprt.com/cd/04-03/)

So, Google’s choice to make the personality resemble a human-less individual made an actual human individual much happier. This process clearly requires a nuanced approach.

How to Be Yourself

The great enemy of clear language is insincerity. When there is a gap between one’s real and one’s declared aims, one turns as it were instinctively to long words and exhausted idioms, like a cuttlefish spurting out ink.

—George Orwell, Politics and the English Language

Creating a consistent, appropriate personality that expresses itself clearly and elicits the right emotional response in the right people isn’t magic—it’s mostly science, with a little bit of art. To make an emotional connection with people, you need to understand those people and what they’re emotionally connected to. Otherwise you’ll create the personality you want to be friends with, and you’ll convince yourself it’s who they want to be friends with too. We’re all very good at rationalizing our choices.

To create interfaces that are meaningful to actual humans who have no relationship to your company, you must listen to them. This means doing user research before starting the design work, and continuously as you create and refine your interface and personality.

This is not optional. You need to hear how real people talk about the specific services you provide, and how they talk about their day and see their problems. Your goal is to hear and understand what your users value and how they talk about it—not so you will mimic them, but so you will be intelligible to them. You must rid yourself of your internal phrasings and find new ones that seem natural to your users. This is the core of the challenge—using language to influence the emotional state of your customer in different contexts and at different points in the interaction. You need to understand their full range of potential emotional states and contexts, and acknowledge and anticipate the negative emotions. Consider the anxious, confused, overwhelmed and skeptical, the bored, the hangry, and the frustrated. Only by working through the potential negative scenarios with other people will you find the right balance of clarity and humanity to help them connect.

Listen for their tasks, too, of course—those things they expect to use the system to do. You need to understand their goals and aspirations and how what you’re trying to do fits into their lives. How does interacting with your product or service help someone be the person they want to be? And how do you prove that this is the case?

In addition to just plain eavesdropping, conduct interviews and listen to your users’ language. Ask representative target customers about their typical day. Just be quiet, and let them speak. Do this a half-dozen times. Then go back through your notes and pull out all the nouns and verbs. This will tell you what your customers do, and the words they use to describe what they do. As you develop the personality and vocabulary for your interface, including labels and phrases for actions, use these notes as a reference. The goal isn’t to sound like a customer; your interface isn’t a peer. The goal is to be meaningful to your customer and trigger the right set of associations.

Learn to like people

To script interactions between humans and machines, it’s helpful to look at how screenwriters script dialogue. My friend, screenwriter and all around good guy Josh A. Cagan, told me that the secret to writing dialogue lies in practicing the difficult discipline of loving your fellow humans:

You have to like people. You can’t hate people and do your job effectively selling ideas and concepts to people. Of course all of us get sick of other people, but I think people are good at their core. They have ideas that don’t jibe with mine and they try to get what they need in bad ways. The secret sauce is that it’s awesome to have people psyched about the things you’re excited about in different ways for different reasons.

Adopting this attitude and making it a mantra will make a difference.

I love sandwiches. I’ve had jobs making sandwiches. I can tell when a sandwich has been made by a sad sandwich maker who has little love for the craft or for the customer. The result is slapped together and unbalanced. The same is true of interactive design. You can tell which products are made by organizations who talk about people, and those who talk about “eyeballs” and “uniques.” A cynical approach to people results in impersonal, system-centered design with a slick veneer of marketing.

And as Josh told me, liking your customers and valuing them doesn’t mean identifying with them. It means you appreciate that they have a different perspective. You must care about them, or you can’t expect them to care about you.

Clarify your values

You need clear values to create a personality with integrity. Values sound like something high-minded and abstract, something that calls on bureaucratic lyricism. But every business has a starter set. Values are implicit in the business model, and denote the exchange of value between the business and the customer. Unexamined values tend to come from an attitude of “we’re here to make money doing stuff.” This leads to a bland marketing tone that won’t stand out. And you can’t adopt values that run counter to how you make your money.

Defining and clarifying values is an activity that requires the input of key organizational stakeholders. And it must take place in the context of creating a living interaction between the system (representing the organization) and the customers. Personalities go wrong when the people at the top write up a set of abstract core values or brand guidelines that eventually find their way to a design team where they must be interpreted into a living, interactive experience.

Start with your values as a company and put them in human terms. Unlike many mission statements, these statements should sound like something a real person would say in conversation—that’s where you’ll find the energy and life. To do this, gather key people in a room with a whiteboard, or over a video conference, or on Slack, and have everyone fill out a mad lib (Fig 4.1).

Fig 4.1: The blanks in these mad libs prompt key people in your organization to frame values in human terms.

This can also work as a workshop-style exercise in which small groups discuss and fill in the sentences together, then have a larger group discussion about the answers (Fig 4.2). The important thing is that it’s a collaborative process subject to an open discussion, rather than something handed down from on high.

Once you’ve clarified your values with that exercise, you can start thinking about how your product or service fits into the lives of others. Another mad lib template can work well here (Fig 4.3). Think of the qualities that describe you, and those that you admire and aspire to. Think of the ones that truly differentiate you (Fig 4.4). This can help you recognize that your organization may mean something different to your customer than it does to you. As the maxim goes, you are not the user—forgetting this is the path to a forgettable outcome.

As you and your team design your system, ask yourselves if it sounds and behaves in accordance with these values and qualities.

After doing this exercise, with your team, make a list of all the words you want your audience to use to describe you. Then make another list of all the adjectives you want to avoid. Narrow your list down to three positive adjectives that are unique to you, and three that concern you the most. Use those words to guide all your work.

Fig 4.3: Another exercise asks people to think of their organization as a person, identifying adjectives that can serve as potential personality traits.

If you focus on what you have to say before thinking about how you sound, you’ll have an easier time sounding right. Think of it as drawing the right style out of the subject matter rather than attempting to apply authenticity like a veneer. You need to know who you are to accomplish this. Otherwise, it’s easy to fall into abstractions. Lead with the functions and flow that reflect what your customers are already concerned about and you can inhabit existing neural pathways rather than carving new ones.

Know your role

Some organizations are concerned about being “too conversational,” by which they mean “too informal.” But being conversational doesn’t imply anything about the seriousness of the conversation or who is having it. Doctors have conversations. Bankers have conversations. Funeral directors have conversations. Most of these conversations happen well within the bounds of professional propriety.

If you’re designing a banking system, it should sound like a reliable, helpful banker. A funeral planning system should sound like a compassionate funeral director. And if you’re designing a game with a shrewd adversary, it should sound like a malevolent, self-important synthetic intelligence (Fig 4.5).

There are plenty of exercises that can help you imagine your product’s personality. What kind of car would your application be? Or is it a tree? These kinds of exercises can be a fun way to get the conversation started but often feel too abstract to be applicable to system interactions.

My own research has shown that if you try to determine which celebrity your interface should emulate, it always comes up with George Clooney! So, don’t even bother—just figure out the actual human analog for the role you play in the lives of your audience. Real estate agent? Maître d’? Bike shop mechanic? You’ll want to streamline the language a bit to be appropriate to use online, but this will give you a good starting point.

For instance, a skate shop can adjust their jargon to be more welcoming to people who wander in off the street as well as to hard-core skaters—it would be jarring if a skate shop sounded like a bank. Or the other way around:

Our mortgage refi options are sick!

There are alternatives to the twin poles of technocratic and too cute. The fundamental characteristics of the personality should be stable. However, personalities adopt different tones depending on subject matter, and context.

- Identity. Is the product the face of the organization? If not, how are they related? When customers interact with the system you’re designing, are they interacting with the company, the service, or a named agent? For example, Amazon offers interactions as Amazon, the ecommerce platform, Kindle, the ereader with associated services, and Alexa, the named agent accessible through the Echo speaker. Google Home’s Google Assistant takes a different approach, lacking gender and a separate identity. The degree to which the system exhibits its own identity sets expectations for functionality and level of familiarity.

- Expertise. How much should the user expect the system to know, and about which topics? A system in the role of a real estate agent should know about mortgages and the housing market. A banker should know about interest rates and savings accounts. A system in the role of a transactional bank teller will express expertise differently than a private banker or financial advisor.

- Mood and attitude. In Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, Douglas Adams spoofed the idea of giving computer interfaces human personalities. One of Adams’s most famous creations is Marvin the Paranoid Android. Marvin’s a severely depressed robot, the product of the Real People Personalities designed by the Sirius Cybernetics Corporation, and a cautionary example of making computers all too human. Most actual interfaces are neutral and slightly positive; the most common mood they demonstrate is some variation of cheerful. Apple’s Siri can display a bit of snark in its responses. It’s worth defining this explicitly, especially if you want to have a more human personality.

- Relationship. Do you see the system as an advisor, a teacher, an assistant, or simply as a tool? The greater clarity you have about the relationship you have with your customer, the better you’ll be able to create a cohesive personality that offers the right cues. Again, many systems will include aspects of multiple relationships.

Figure 4.5: GLaDOS (Genetic Lifeform and Disk Operating System) is the character of a sinister and witty AI antagonist in the videogame Portal that sounds like synthesized text-to-speech, but it’s voiced by a human actor.

Personality in Action

Aspects of the personality’s role and attitude can change with different parts of the system—just as a customer might encounter different representatives of the same company. At various points, it will be natural for the system to sound more like a supervisor or a helpful customer support agent. This will set different expectations from talking to a sales person (or a malevolent intelligence!).

It’s in the mundane details of the interactions where a robust personality can really make a difference.

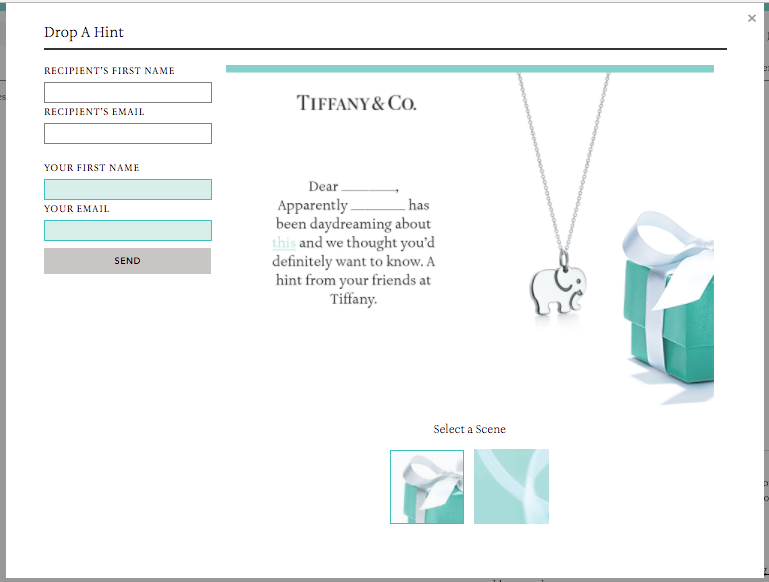

Tiffany & Co. is a very old and famous jewelry brand. Tiffany sells a very particular style of luxury gift, and have a clear sense of their role in their customer’s life. The core customer interaction is selecting and purchasing a gift. On their website, they offer a very Tiffany-style way of allowing a customer to signify to someone their desire for a potential gift (Fig 4.6). The interaction is presented as a hint the store just happened to pick up from someone daydreaming. A generic “email this to a friend” message would come across as crass and, ahem, tarnish the brand. On Amazon.com, a Tiffany-style message would seem fussy and overbearing.

Personality pitfalls

When the personality of your system depends on language, and you have an international audience, it’s necessary to adapt that personality to the local language and culture. Simply translating for meaning won’t be effective. The marketing and advertising industry figured this out in the 1960s, and coined the term transcreation. Transcreation is about creating a message that evokes the same emotions and carries the same implications from one culture to the next.

The Amazon Echo is a personality to watch as it evolves to meet the needs of new markets. Amazon has dubbed Alexa’s more idiomatic phrases, “speechcons”:

In February, we announced SSML support for speechcons in the US. Speechcons are special words and phrases that Alexa expresses in a more characterful way, making the user experience even more engaging and personal. Today, we are excited to announce that developers in the UK and Germany can now use speechcons to build more creative voice experiences with UK English and German words and phrases. This means you can now build UK English and German Alexa skills that pronounce common words in a more natural manner. You can use regionally specific terms such as “Blimey” and “Bob’s your uncle,” in the UK and “Da lachen ja die Hühner” and “Donnerwetter” in Germany. (http://bkaprt.com/cd/04-04/)

Alexa also now has the ability to speak in a whisper, ostensibly to sound more human. I have listened to the whispering, and I can report that, as of this writing, it’s about as creepy as stop-motion puppets wearing the same lifelike face.

Fig 4.7: Some design decisions are mysterious. This is definitely not appealing to anyone who’s ended a difficult relationship.

Fig 4.7: Some design decisions are mysterious. This is definitely not appealing to anyone who’s ended a difficult relationship. Missteps can also be instructive. At every point, in every role, your interface should come across as supportive and on the side of the customer, even during less positive interactions. Don’t do what this financial software did (Fig 4.7) and put yourself in the role of a clingy romantic partner. That is not cute, or adult. No one wants that.

A Few More Words About Words

To find the joy in fellow humans, and to give it back through systems that are sufficiently humane, it helps to rediscover the joy of language. It also helps to banish the banal habits that begin to rub off from frequent exposure to worst practices.

Our greatest accomplishments as verbal animals include jokes and poetry. Our most shameful sin is soulless corporate jargon.

Good humor

A user interface is like a joke. If you have to explain it, it’s not that good.

—Martin LeBlanc, founder of Iconfinder

Humor is a critical dimension of human communication and we still don’t know exactly why it exists or how it works. There are several theories—emerging from various academic fields, particularly in education and instructional design—that attempt to explain it. Teachers are especially interested in the challenges of holding attention, and imparting information and humor seems to help both.

Humor relieves psychological tension and can help resolve incongruity between an idea and a situation. Over the course of human evolution, I figure enough of our ancestors escaped death by doing something unexpected and delightful, so perhaps we ended up with genes for that. The bores must have relied on camouflage!

Whether and how an interface uses humor is a key part of the tone and personality. Like interaction design, humor depends on context and timing. Playfulness can make a situation more enjoyable, or the attempt can backfire spectacularly. What is funny to one person, might be incomprehensible or offensive to another.

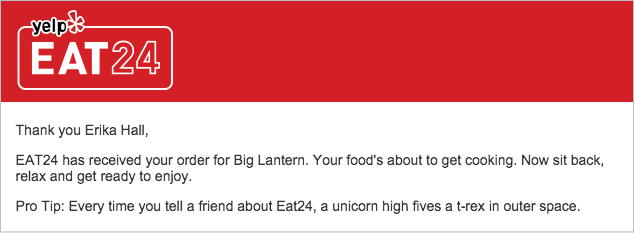

Writing a book leads to ordering a lot of meals online. One of the greatest gifts the internet has bestowed on us is replacing a drawer full of takeout menus and reducing the threat of awkward telephone conversations. In writing this book, I’ve had the opportunity to review dozens of greetings, reminders, calls to action, “helpful” tips, and status updates about my meals.

After innumerable visits, I’ve found that the communications start to sound like something out of the Sirius Cybernetics Corporation. Too needy, too chatty, and trying too hard. A unicorn high-fiving a t-rex is mildly funny the first time round (Fig 4.8), but by the twentieth time in a month, I want the unicorn to impale the t-rex in the alley behind the Thai place. Interfaces like this arise because designers and writers think of them as abstract descriptors rather than real-life customer interactions—and interactions that happen repeatedly.

Begin with the mood and the state of mind of your customer. In this case, they’re likely to be hungry, possibly impatient, and probably also seeking a show on Netflix at the same time.

I asked my buddy Josh for advice on how to avoid unsuccessful attempts at humor:

Here is the easiest way in the world to not be not-funny. Don’t try to be funny. The more that you understand the folks you are writing for the more you will find the things that give them pause or tickle their fancy.

Food delivery company Seamless expresses a level of triumphal enthusiasm I save for major accomplishments like finishing marathons or filing my taxes (Fig 4.9). They demonstrate how little they know about me with a random list of activities: roof parties, commutes, fight club. Also, they bury the crucial information—how soon is food?—below unnecessary canned cheer.

Fig 4.9: Seamless should lead with the important information: when will I eat?!

There’s nothing more delightful than being able to summon hot, tasty food to my door with no effort. No need to try so hard. How about:

We estimate your food will be at your door between 8:25–8:35pm.

Thanks again for using Seamless and supporting local restaurants!

I’m lucky enough to live walking distance from a small grocery store where I buy most of my food. When I’m not writing a book, I stop in a few times a week. The family who runs it knows me and my shopping habits as well as any online retailer. We usually chat briefly as I check out. Sometimes they comment on my purchases. If one of them ever said, “Here’s your receipt! Deliciousness is in the works! Enjoy making dinner while you binge-watch TV or talk to your dog,” I would find it odd and uncomfortable.

The British are often very good at navigating tone in verbal humor. The Guardian allowed a charmingly exasperated human voice through in a photo caption (Fig 4.10). This works because it’s truly unexpected. If every photo caption spoke to the reader like this, the effect would wear off quickly.

Fig 4.10: This is delightful. It’s part of a satirical opinion piece on British government (http://bkaprt.com/cd/04-05/).

Fig 4.10: This is delightful. It’s part of a satirical opinion piece on British government (http://bkaprt.com/cd/04-05/).

Some of the best humor comes from playing against expectations. Fast-food brands are generally upbeat about their mass-produced, industrial foodstuff. I’ll leave you with one of the darkest voices on Twitter, the parody account Nihilist Arby’s (Fig 4.11)

Expose yourself to excellence

The poet doesn’t invent. He listens.

Language is a social phenomenon you are programmed to imitate. Your social self wants to mimic. Borrowing from online banking sites or BuzzFeed will make you parrot the mush without realizing. You’ll come out a bureaucrat, or a clickbait zombie.

Strong verbal design is so rare online that looking for best practices risks muddying your thoughts. It’s necessary to understand the conversational conventions in existing digital systems, particularly in the domain you’re working in, be it shopping or banking or real estate. However, if you want to stand out for your clarity, humanity, and perhaps even for your charm, expose yourself to a wide range of voices in areas of verbal excellence.

Often in my work, I’ll scour the internet and app stores for examples of good interface design. And often, I come up short. There always seems to be more clichés and compromises than models to emulate. The same goes for language. It’s good to see and hear what exists to identify conventions, but for inspiration, get out into the real (atoms, not bits) world. Go to places where your customers are likely to go. Start listening to how people in different roles really talk. Listen for word choice, sentence structure, and tone. Collect and catalog voice samples. Both good and bad. Carry a notebook. Take screenshots. Pop them into a Google doc, print them out and put them on a wall, or drop them into Slack. Describe them and note what makes them effective. Send your team out on Friday to eavesdrop all weekend and report back on Monday.

Also, clean out the clichés and pat phrases by reading some poetry. Aloud. With your team. Poetry is your best source of deliberate intentional language that has nothing to do with your actual work. Reading it will descale your mind, like vinegar in a coffee maker.

I recommend beginning with the Imagists, a group of early-twentieth-century English and American poets. The Imagists favored common speech and novel rhythms to create clear, precise images. (Hence, the name.) Well-known poets include William Carlos Williams, Hilda Doolittle, Amy Lowell, and Marianne Moore.

Ezra Pound, one of Imagism’s founders, wrote a manifesto for poetry that would be equally applicable to creating interfaces:

Use no superfluous word, no adjective, which does not reveal something.

Don’t use such an expression as “dim lands of peace.” It dulls the image. It mixes an abstraction with the concrete. It comes from the writer’s not realizing that the natural object is always the adequate symbol.

Go in fear of abstractions. Don’t retell in mediocre verse what has already been done in good prose. Don’t think any intelligent person is going to be deceived when you try to shirk all the difficulties of the unspeakably difficult art of good prose by chopping your composition into line lengths.

Ezra Pound would probably not be a fan of empty abstractions like “innovative solutions” and the Submit button.

“This is Just to Say” by William Carlos Williams is a terrific example of this compelling economy of language.

I have eaten

the plums

that were in

the icebox

and which

you were probably

saving

for breakfast

Forgive me

they were delicious

so sweet

and so cold

That is a precise image that sticks, capturing an ephemeral moment. No abstractions. All familiar words. It has persisted in popularity since its publication in 1934 and has become the source of many snowclones. (A snowclone plays on the original form, or clones it, but with new words substituted.) The term was coined by linguists Geoffrey K. Pullum and Glen Whitman on the Language Log blog (http://bkaprt.com/cd/04-06/). These poetry jokes are one of the more delightful things to pop up on Twitter with regularity (Fig 4.12).

Fig 4.12: New variations on this poem seem to appear weekly, such is the power of the form.

While reading a bit of verse is unlikely to transform you into the William Carlos Williams of user experience, it will have the same beneficial effect as considering any elegant system or cunning artifact. Strong examples of clear evocative language will inoculate you against creeping banality.

Contemplate the deceptive simplicity, and the way the line breaks hold space in time. Capable and confident writers and designers do not need to embellish. Williams’s poem lodges in the brain because it’s conversational; the spare voice of the poem is speaking directly to the unseen owner of the plums.

Avoidably ugly words

Could I put it more shortly? Have I said anything that is avoidably ugly?

—George Orwell, “Politics and the English Language”

And, finally, a fantastic way to clarify voice and values is to discuss avoidably ugly words, those you must never use when speaking for the system you’re designing because they are imprecise or empty.

It is often easier to start with the negative space. Think of what you don’t want to sound like and try that first. Make your interface as bureaucratic or as robotic as you can. Scour Urban Dictionary for verbs you’ve never heard and slap them on buttons. Then, once you’ve warmed up and had some fun, give the real voice a try.

Avoidable words might be meaningless filler, taking up space and time without benefitting the user. Or they might be clichés or moldy idioms that any one of a million products or services could use, diluting meaningful differences. I’ve worked with more than one world-class organization that added “world-class” to the list of words to avoid.

Here’s a list of words I wish every organization would avoid for the sake of clarity and interest. This is just a start. I’m sure you’ll have a terrific time adding many of your own:

- Compelling. This is a word people often use when telling others how to write. It’s wishful, not descriptive.

- Helpful. Never self-describe as helpful. Let your customers decide that.

- Quick. Is it, really?

- Innovative. This word used to mean something. Now we’ve used it up. The same goes for intelligent and smart.

- Important. If you call one thing important, what does that make everything else? Say why it’s important, then delete the word important.

- Check out these hot topics. This phrase adds nothing. You might as well just have a list. Be specific. Describe.

- Oops! In 2011, Republican candidate for president Rick Perry said “Oops” when he forgot his answer during a debate and it ended his campaign. Adults restrict the use of this word to inconsequential mishaps, such as spilling a beer on your dog. When you’re speaking for a system, choose adult words that show you own your errors.

Remember: If you have to say it, you probably aren’t it. And while we’re at it, here are a few more functional phrases that are best abandoned in favor of more intentional choices:

- Submit. Stop using it as a button label. Forever. Describe the specific action the button triggers.

- My [items]. As more interfaces speak directly to customers, this usage will eventually disappear. Still, it wouldn’t hurt to hurry it along. Otherwise, you’ll end up with “We Apologize” and “My Account” colliding, as in United’s 404 page (Fig 4.13).

Fig 4.13: My Account is right next to Contact Us. Very strange. - Click here. I’ve heard arguments for the most generic all to action as an affordance for otherwise obscure links, but it’s a crutch for interaction that won’t work as interfaces increasingly support switching modes from voice to text and back again.

Making an explicit list of avoidable words is necessary because language is a social phenomenon, and repeating the phrases we hear every day—no matter how threadbare—is the easiest thing to do.

It’s all about you

If you’ve ever spoken to someone who refers to themselves in the third person, or seen an interview with a celebrity who does, it’s probably struck you as strange. In natural conversation, people speaking to one another say “I” or “we” and “you.”

There’s been a lot of back and forth over the use of “my” and “your” in interfaces. Although the roots go deep, let’s put this hoary debate down like the zombie attacker it is. Windows 95 introduced My Computer in 1995, followed by My Yahoo!, a customizable dashboard. Then, like mushrooms after a rain, a million mindless imitators emerged. It’s as if the user has printed out labels and stuck them to various objects: My Lunch, My Desk, My Red Stapler. Instead of reinforcing a sense of ownership and agency, this feels presumptuous and alienating. For a while the iTunes i0S app navigation bar included both “My Music” and “For You”, which is confusing and brought up a lot of feelings about digital rights management (DRM).

To feel conversational, digital systems should be designed to act as true conversational partners. Things belonging to the company that created the system, such as a feature or privacy policy, are “ours.” Things belonging to the user, such as a profile or shopping cart, are “yours.” Anything that’s just a part of the overall experience doesn’t necessarily need a possessive pronoun at all.

Amazon has a clear relationship with the people who use their services (Fig 4.14). In every instance, they address their customers as “you.”

The future may take care of itself in this regard as voice user interfaces (VUI) are becoming more popular, especially for interacting with one’s home and car. It’s one thing to see an awkward label, and another to hear it spoken aloud: “Now playing David Bowie from my music library.” No one wants to be in a domestic situation in which the digital butler is asserting property rights.

Going non-verbal

Human conversation is uniquely verbal. Among all the creatures on Earth, only we use words. However, the words we use represent only a fraction of what we communicate overall to each other. Because it’s possible to incorporate language in a very human way, in translating a human personality to a digital system we lean heavily on language. The same is not true for the nonverbal cues that are a significant part of how humans communicate. Body language, facial expressions, and vocalizations convey essential information that we use to interpret the meaning of the message. A smile, a nod, a touch of the hand, a whisper, or a shout can infuse the same words with warmth, credibility, urgency, or levity.

In the absence of a physical presence, we seek supplemental social cues where we can find them. Over the last few decades, we’ve learned a lot about computer-mediated communication. Email, texting, and social media generate their own records for us to observe and reflect upon, and these emerging forms of communication are the subject of countless studies, as well as less academic discussions. Most people who communicate online in English recognize that typing in all capital letters is TANTAMOUNT TO SHOUTING. This is a convention.

Digital systems can’t use the same body language because, at least for now, computers don’t have human bodies. Many of their advantages come from this fact.

A 2015 study by researchers at Binghamton University found that text messages ending with a period seemed less sincere (“Texting insincerely: The role of the period in text messaging” Computers in Human Behavior Volume 55, Part B, February 2016). Without explicitly positive information, if you know there’s a human on the other side of the computer, it’s easy to take a more negative interpretation. Online communities tend towards trolling and flame wars much more than spiraling lovefests.

Computer-mediated interactions, even in a conversational manner, may be less stressful simply because people get less emotionally involved. One of the landmark studies in behavioral economics used magnetic resonance imaging to observe cognitive and emotional processes in people playing the Ultimatum Game with both other humans and computers. In the game, one player proposes a way to divide a sum of money and the other accepts or rejects it. The study showed that participants had a much stronger reaction to perceived unfairness from a computer than from a human. (“The neural basis of economic decision-making in the Ultimatum Game” http://bkaprt.com/cd/04-07/). This study is often cited to explain why people prefer computer-mediated communication, even as compared with humans they know and like.

The challenge of conveying emotion accurately in a few words has led to the popularity of emoticons, emoji, and animated GIFs. The first-recorded emoticon dates to 1635 Slovakia. Ján Ladislaides, the Notary to the Town of Trenčín, drew a smiley next to his signature to indicate the documents he reviewed were in order.

The most appropriate emotional embellishment depends on the context of the communication and the personality of the system. I’ve already mentioned the Quartz news app which includes emoji as part of its interface, but it would probably be off-putting for your bank to text you a sad face to let you know that your account is overdrawn. For many systems, creating appropriate nonverbal cues requires specialized visual, industrial, and sound designers. For any of these to be effective, however, they require a personality that’s clearly defined, and articulated in words.

Excelsior!

It all comes down to valuing your customer and knowing your values. Tacking on a friendly face in bad faith won’t make the underlying system more meaningful or sustainable. That’s a tough act to keep up.

Products and services that succeed in having the right amount of the right personality do so because thoughtful humans cared enough to be honest and intentional. Clear, collaborative conversations are important throughout the entire process. Next, we’ll look at how to work with your team to do this. Creating a design process is just another type of interaction design. Designers are also people with habits and biases who work in a context.

Easy-peasy, right?