7

Agree on a Plan and Follow Up

Never grow a wishbone …

where your backbone ought to be.

—CLEMENTINE PADDLEFORD

How to Gain Commitment

and Move to Action

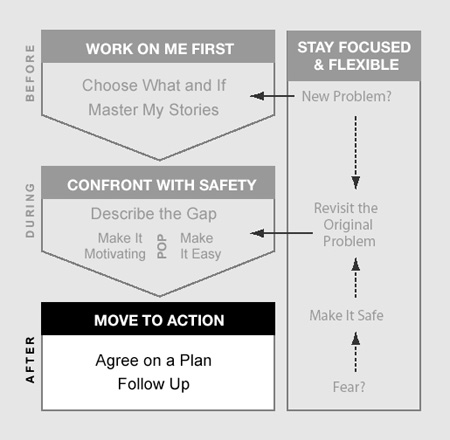

By now you’ve done a lot of work. You noted a problem and decided that the gap was worth confronting. You told yourself the whole story and took care to step up to the right issue. You then worked hard to deal with both motivation and ability issues. You even dealt with a new problem, used your bookmark, and then solved the original problem. Jointly, you found solutions that seemed promising. Good job!

But don’t exhale too quickly. The way you complete a crucial confrontation is as important as the way you start it. If you do this well, you build commitment and establish a foundation for accountability. If you don’t finish the job—if you swap your backbone for a wishbone—you set yourself up for a whole new set of problems. Let’s look at some of these challenges and then explore the skills and tools master influencers use to plan and follow up.

PREDICTABLE PROBLEMS

Certain problems are so common that after you hear no more than a sentence and a half, the whole messy situation comes to mind. For instance, see how long it takes before you can identify where these common problems are headed.

How Good Is Your Crystal Ball?

At the end of last week’s meeting Jane said to Joe, “So you’ll get the report done?”

“Absolutely,” Joe exclaimed, mentally figuring how to fit another assignment onto a plateful of tasks so overflowing that it was starting to interfere with his bowling.

A week passes, and Jane is at the door: “I needed that report yesterday afternoon. Can I have it now?”

“Now? I had that scheduled for next week,” Joe laments. Jane responds by rolling her eyes: “You must have known I needed it.”

Joe hates that eye thing and responds under his breath: “My crystal ball was at the cleaners.”

“What was that?” Jane asks, raising her voice.

“Nothing,” Joe grunts.

“You said something!” Jane accuses him.

“I said ‘My eye is on the ball, and I mean it!” Joe lies.

What Exactly Is Creativity?

During a formal review discussion Barb talked to her direct report Johnson about being more creative. Her exact words were, “During the next quarter I want you to use more creativity. You know, come up with more ideas on your own.”

In an effort to be more creative, Johnson did indeed come up with more ideas on his own, just as he was asked to. That was the good news. The bad news was that he also implemented many of his ideas without involving Barb or anyone else. He interpreted the request to be more creative as permission to do pretty much whatever he pleased.

When Barb eventually learned that Johnson had changed the company’s entire inventory system and hadn’t given her so much as a heads-up, she blew a gasket and told him that he had gone well beyond his authority. He responded by arguing that he was just trying to be more creative and now she was taking him to task for doing what she had asked him to do all along.

Must We Play Word Games?

Dad is stewing. It’s a sultry summer night, and for the last hour and a half he has been staring at the clock. During that time he has tried very hard not to get angry. It’s now 1:24 a.m., and his daughter opens the door. Dad shouts: “Shelly, you’re really late!”

“No, I’m not, Dad. Last week my friend Sarah didn’t come home until nine the next morning; that’s really late.”

“Don’t be smart-mouthed with me!” Dad retorts. “You’re supposed to be in by midnight, and you’ve been coming in late all month.”

“You’re right” Shelly says with a sly smile. “I have been coming in at about 1 a.m.. for a month, ever since my birthday. And you haven’t said one thing about it at all until now. I thought it was okay.”

Dad comes back with his best quip: “Well, ah, ah, hmmm….”

DON’T ASSUME

How long did it take before you recognized the problem in these examples? Jane and Joe made a sketchy plan. Without agreeing on a specific deadline, that plan was doomed from the get-go. They had to play “read my mind” or “take my best guess.”

Johnson and Barb faced a different problem. The assignment included who was going to do what by when, but the details about the what were not clear. She told him to be creative, but that term is far too subjective. Once again, an accident waiting to happen.

Finally, Dad and daughter represent still another issue. By not confronting his daughter for coming in late (following up on a previous agreement) for several days running, he let Shelly assume that what she was doing must have been okay. Like it or not, Dad had given his tacit approval. At least that was what Shelly thought.

Nailing Jell-O

These problems are so familiar because we create them all the time. We finish a perfectly good crucial confrontation and then make sketchy plans that are peppered with vague, unspoken, and unshared assumptions. All bets are off. We can’t hold people accountable to do something, sometime, somehow. It’s like trying to nail Jell-O to the wall.

A complete plan, in contrast, assumes nothing. It leaves no detail to chance. It sets clear and measurable expectations. It builds commitment and increases the likelihood that we’ll achieve the desired results. It also enables both parties better to have the next discussion—for accountability, for problem solving, or for praise.

THE SOLUTION: MAKE A PLAN COMPLETE WITH WWWF

The key to making a complete and clear plan, free from all assumptions (and thus improving accountability), is to make sure to include four key components:

![]() does What

does What

![]() by When

by When

![]() Follow-up

Follow-up

As we just noted, problems typically arise because assignments have only two or three of these components. Let’s look at each of the four and see what the experts have taught us from the trenches.

Who

This first issue is the easiest: Someone’s name has to be attached to each task. But there’s the rub. Someone’s name has to be attached. Someone needs to be in charge or accountable. At the end of a meeting the supervisor says, “Okay, we should get it done by Friday at noon.” Come Friday, nothing is done. The boss exclaims, “Where is it?” And the finger-pointing party begins.

We is too vague. In business the term we is often synonymous with nobody. There is no we in accountability (but let us not forget that there is in weenie). Parents often make this mistake. Mom says to her kids, “Now before you go play with your friends, let’s clean our rooms.” Later, to the frustrated mom, the kids whine, “But Mom, you said you’d help.”

For accountability to work, a person needs to know what he or she is expected to do. If the task requires many hands, each person needs to know what his or her part of the assignment is. The “team” can be as ambiguous as “us” or “we.” Therefore, when it comes to large jobs, make sure one person is responsible for the whole task and then link specific people to each part.

What

Deciding exactly what you’re after can be challenging. Johnson ended his performance review with Barb by accepting the responsibility to be more creative during the next quarter. So they followed the rules, right? It was clear who would do what by when. Not exactly. Barb needed to provide a detailed description of the exact behaviors she was looking for: “By being more creative I mean I’d like you to come up with more product ideas on your own. I’d love for you to come to our weekly meeting and present new ideas for improvements. The same is true for solutions. When you see a problem, rather than asking what needs to be done, come up with suggestions and then present them to me.”

Ask

When you end a crucial confrontation and are deciding exactly what to do, don’t take the what for granted. Ask if there are any questions about quality or quantity. Ask if everyone has the same characteristics in mind. Ask what might be confusing or unclear that has to be clarified now, in advance.

Contrast

If you suspect that other people are likely to misunderstand you, use Contrasting: “I want you to think of new plans. I don’t want you to implement them until we’ve had a chance to talk, but I do want you to take the initiative to present them.” Those of you who have had cataract surgery recently are familiar with the hospital version of this technique. A nurse draws (in magic marker and on your forehead, no less) an arrow over the eyeball that is about to receive the surgery, meaning “this eye, not the other one.” When the stakes are high, leave nothing to chance. (How many wrong surgeries were performed until someone came up with this trick?)

By When

Time is a concept of our own construction. It comes with specific names and numbers. It’s quantifiable and exact. Thus, when it comes to setting follow-up times or deadlines for change, you’d think there would be no room for confusion. But we find a way. For example, consider the expression “I need it next week.” This may be specific. If you are perfectly happy to receive the finished product any time in the next week, you have a clear agreement. Technically, the expression promises nothing before 11:59 P.M. on Saturday. However, if you need it before 5:00 P.M. on Friday, say so. If you need it on Wednesday, clarify. If you need it by noon on Wednesday … you get the point.

What makes this issue particularly intriguing is that the more urgent the task and the more critical the timing, the more vague the instruction: “This is hot; I need it ASAP.” “Get right on it.” “Hey, did you hear me? This baby is top priority. I need it yesterday.” These terms of urgency are train wrecks waiting to happen. Think of it this way: “ASAP: the do-it-yourself ulcer kit.”

This problem comes up at home too. The following are statements begging for different interpretations: “Don’t be late.” “I’ll get that to you soon.” “You need to clean up your mess in the kitchen.” We could be wrong about this, but it seems that teenagers have an amazingly well-developed ability to find the cracks in incomplete plans and use them to their advantage. Clarity helps you fill in the cracks.

Follow-Up

Once you’ve clarified who is supposed to do what and by when, the next step should be obvious: Decide when and how you’ll follow up on what’s supposed to happen. Perhaps both of you have taken an assignment to do something to resolve the problem but things have come up. When it comes to problem solving with your direct reports or children, you don’t necessarily want to leave them to their own devices, particularly if the task is difficult and the people who have to deliver on the promise are unfamiliar with the territory. By the same token, you don’t want to be checking up on people every few hours. Nobody likes that.

When choosing the frequency and type of follow-up you’ll use, consider the following three variables:

![]() Risk. How risky or crucial is the project or needed result?

Risk. How risky or crucial is the project or needed result?

![]() Trust. How well has this person performed in the past; what is his or her track record?

Trust. How well has this person performed in the past; what is his or her track record?

![]() Competence. How experienced is this person in this area?

Competence. How experienced is this person in this area?

If the task the other person has agreed to do is risky, meaning that bad things will happen if it is not done well, and if it is being given to someone who is inexperienced or has a poor track record, the follow-up will be fairly aggressive. It’ll come soon and often. If the task is routine and is given to someone who is experienced and productive, the follow-up will be far more casual.

The two most common methods for checking on progress are scheduled and critical event follow-up times. For routine tasks, schedule a time to see how much progress is being made. Often this is done during a routine meeting at which you’ll already be together anyway. With more complicated projects, base the follow-up on milestones or key events: “Get back to me as soon as you complete the initial plan.” Or you can combine the two: “If you don’t have the plan completed by next Tuesday at noon, let’s meet and discuss ways to speed things along.”

If you don’t have a defined relationship, follow-up can require more creativity. For example, a woman who confronted an inappropriate behavior from a male coworker worried that confrontation might not put an end to the behavior, and so she built in a follow-up. She concluded by saying, “Would it be okay if in a month we met in the cafeteria for lunch? I’d suggest our first agenda item be ‘Am I acting weird toward you since this discussion?’ and ‘Has the behavior stopped from my perspective?’ What do you say?” This candid, sincere, and respectful request was accepted. And when it was, this skilled woman gained four weeks of clear accountability. The behavior stopped.

If you find yourself in a crucial confrontation where you’re worried about backsliding, never walk away without agreeing on the follow-up time.

Micromanagement or Abandonment

How frequently you follow up with another person depends on that person’s record and the nature of the task. How your actions will be viewed by others depends on your attitude and objective. When it comes to following up, ask yourself: What am I really trying to accomplish? If you don’t trust others, your follow-up methods are likely to be seen as audits (“gotcha!”), and nobody likes an audit.

When people feel as if they’re being watched too closely they tend to transmute into “good soldiers.” “Just tell me what to do and I’ll do it.” They “check their brains at the door.” They perceive follow-up as criticism. They feel that they are working for a micromanager and are given no chance to show initiative or creativity. In short, the relationship they have with their boss is not based on trust and respect.

Unfortunately, the sense of abandonment people experience at the other end of the follow-up continuum may cause just as many problems. Cutting people loose is certainly more common in today’s world of empowerment. Leaders don’t want to micro-manage. They’ve felt it, they hate it, and they don’t want to deliver it. Micromanaging is bad, and so leaders scarcely follow up at all. Good goal, bad strategy.

Other factors also contribute to an excessively hands-off style. Many leaders (and parents) don’t believe they have time to follow up. They give a great deal of freedom to others, even to people who have been fairly unreliable. Nowadays people in authority spend so much time traveling, answering e-mail, and sitting in meetings that they don’t even notice that they don’t follow up very often.

Unfortunately, this hands-off style is rarely interpreted positively. People don’t say, “I understand. The boss is so busy that he can hardly find time to follow up.” More often than not employees conclude, “The boss doesn’t care about me or my project.” Busy parents suffer the same fate. Busyness is interpreted as apathy, and this harms both the relationship and the results.

When it comes to how and when you follow up with others, your intentions will have a huge impact.

How about you? If you think you may be at risk of being seen as a person who micromanages or who is too hands-off, check it out. When making an assignment, describe the type of follow-up you think is appropriate. Explain why and be candid about your reasoning. Then sincerely ask if the other person agrees with the method. When you both agree on the frequency and type of follow-up and you both know it, you won’t be left wondering if you are being perceived as too hands-off or too hands-on.

Two Forms of Follow-Up: Checkup and Checkback

Who initiates the follow-up discussion? Does the person giving the assignment always take the lead, or are there times when the person taking the assignment follows up? Do a checkup when you’re giving the assignment and are nervous or have questions. You’ve looked at the risk, the track record, and the person’s experience, and you’re feeling anxious or uneasy, even tense. This is the time to use a checkup. You take the lead. Get your PDA or calendar out. Say something like the following: “Since this is such an important task, I’m wondering if we could meet next Wednesday at ten to review how it’s going.” You write it down. You are in charge of the follow-up.

The fact that you’re taking the lead doesn’t mean that you are micromanaging. It means that you own the follow-up. It can and certainly should mean that you’re interested in how the task went, what worked, and what got in the way. If the task is risky enough, the follow-up should be scheduled along the way to make sure that all is going well and that you are available to provide help or coach.

Use a checkback when the task is routine and has been assigned to someone who is experienced and productive. Now that person is in charge. That person checks back. He or she offers suggestions: “How about meeting at our next scheduled meeting?” or “The deadline is two weeks from today. Could we meet next Thursday fifteen minutes before our staff meeting to touch base?”

To achieve the results you want as well as maintain healthy relationships, both checkups and checkbacks can be useful forms of follow-up.

Take Time to Summarize

A planning discussion can be fairly complex and fast-paced, causing us to forget things. Take the time to summarize what’s supposed to go down. It could sound something like this:

“Let me see if I got this right. Bill, you’ll get the nine copies of the report, stapled with a standard company cover sheet, for the meeting Tuesday at 2 p.m. And you’ll check back with me before noon that day if you see any problem. Is that right?”

Bill: “Right.”

“Can you see anything else that we haven’t talked about that might cause a problem?”

When you ask for the other person’s input, it can help bring to light issues that might otherwise cause problems. However, the real power of this question goes far beyond clarifying understanding. You’re checking for commitment. When the other person eventually says “I’ll do it,” that person is much more likely to live up to the agreement. Never walk away from a crucial confrontation satisfied with a vague nod. If you care about gaining genuine commitment, give the other person the opportunity to say yes to a very specific agreement.

AGAIN, FOLLOW UP

First you set a follow-up time:

![]() Should it be formal? Should it be casual?

Should it be formal? Should it be casual?

![]() Should it be a checkup or a checkback?

Should it be a checkup or a checkback?

![]() Should it be based on the calendar or on a critical event?

Should it be based on the calendar or on a critical event?

That’s the thinking you do up front. Next comes the actual act of following up. Guess what: The biggest problem with following up is not that we do it too often despite the fact that many of us have felt micromanaged from time to time. The biggest problem is that we don’t follow up at all. We set plans, create follow-up dates, and then sort of let them drop. How could that happen?

People Forget

Our first problem is that we tend to forget. Life is so fast paced, full, and busy, we can’t keep all the balls in the air at the same time. How are we ever going to remember to follow up on all the promises that other people make? Or that we make? The answer is that we can’t, at least not without help. To keep your promises in front of you, do the following:

![]() Put follow-up dates and times on your calendar.

Put follow-up dates and times on your calendar.

![]() Use sticky notes or computer cues to remind yourself.

Use sticky notes or computer cues to remind yourself.

![]() Put follow-up times on your agendas.

Put follow-up times on your agendas.

Reminding yourself to do what is effective is essential in busy environments and times. Families tend to be particularly bad at this. How many people use computers and other electronic devices when giving assignments to children or loved ones? To most of us that would seem cold and too businesslike: “Dad, I’m your daughter, not an employee.” Nevertheless, the times are changing. Find methods, electronic or other.

People Worry

Another reason people frequently fail to follow up on assignments is that they want to be seen as nice. As one interviews people in organizations all over the world, it’s interesting how frequently the word nice comes up. Question: How would you describe your organization’s culture? Response: Nice. In this case, the word has switched meanings from “pleasant” to “diseaselike.”

Nice

adj. A pleasant, nonconfrontational attitude that eventually kills you

People want to feel at ease, not stressed. Holding others accountable, particularly if you have to be honest, is stressful. So individuals rationalize and choose niceness over following up. It’s not a sellout; backing off is the right thing to do.

Of course, you can believe this semitortured logic only if you believe that being honest and holding people to their promises are inherently stressful and bad. Throughout this book we’ve tried to make the point that people who confront crucial problems are both candid and courteous. They are honest but not “brutally honest.” You can follow up with people and be a decent human being. In fact, the converse is also true: If you don’t follow up, you’re being unkind to everyone. Allowing failure eventually destroys results and relationships.

The tools taught in the preceding chapters are designed to help us be candid and nice, get results and be nice, and follow up and be nice. The scripts you can use for following up are both easy and safe. When you follow up, you ask, “How’s the Southland project going?” or “We scheduled a follow-up on budget improvements. How’s it going?” The purpose of the follow-up is to see what the current status is, how things went, what worked, and what didn’t. The intention is to be helpful and supportive.

Agree on a Plan

We’ve come to the end of our model. We’ve done all we can to confront with safety and now it’s now time to Move to Action. First we agree on a plan and follow-up method. Then we actually follow up.

![]() If we don’t end a crucial conversation well, we’ll have wasted our time and, worse still, are very likely to disappoint people and create unnecessary anxiety. Assignments will drop through the cracks.

If we don’t end a crucial conversation well, we’ll have wasted our time and, worse still, are very likely to disappoint people and create unnecessary anxiety. Assignments will drop through the cracks.

![]() To end well, become an expert at creating a specific plan than includes who will do what by when. Make sure each person is clearly identified with a responsibility. Make sure the what is clearly understood. Call for questions and use Contrasting where necessary.

To end well, become an expert at creating a specific plan than includes who will do what by when. Make sure each person is clearly identified with a responsibility. Make sure the what is clearly understood. Call for questions and use Contrasting where necessary.

![]() Ensure that your plan contains the right and agreed-upon method of following up. The less skilled the person, the spottier his or her history, and the higher the risk, the more frequently you’ll follow up. Candidly talk about your follow-up methods.

Ensure that your plan contains the right and agreed-upon method of following up. The less skilled the person, the spottier his or her history, and the higher the risk, the more frequently you’ll follow up. Candidly talk about your follow-up methods.

![]() Finally, follow up. If things don’t go well, step up to the new crucial confrontation.

Finally, follow up. If things don’t go well, step up to the new crucial confrontation.

Additional Resources

To see how all of the skills fit together in a single interaction, log on to crucialconfrontations.com and watch a video example of a healthy crucial confrontation.