OUR STORIES

Nothing in this world is good or bad, but thinking makes it so.

—WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE

Stories provide our rationale for what’s going on. They’re our interpretations of the facts. They help explain what we see and hear. They’re theories we use to explain why, how, and what. For instance, Maria asks: “Why does Louis take over? He doesn’t trust my ability to communicate. He thinks that because I’m a woman, people won’t listen to me.”

Our stories also help explain how. “How am I supposed to judge all of this? Is this a good or a bad thing? Louis thinks I’m incompetent, and this is bad.”

Finally, a story might also include what. “What should I do about all this? If I say something, he’ll think I’m a whiner or oversensitive or militant, so it’s best to clam up.”

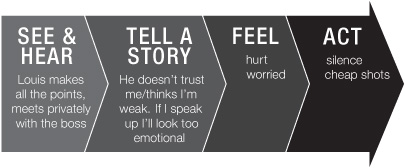

Of course, as we come up with our own meaning or stories, it isn’t long until our body responds with strong feelings or emotions—after all, our emotions are directly linked to our judgments of right/wrong, good/bad, kind/selfish, fair/unfair, etc. Maria’s story yields anger and frustration. These feelings, in turn, drive Maria to her actions—toggling back and forth between clamming up and taking an occasional cheap shot (see Figure 6-3).

Figure 6-3. Maria’s Path to Action

Even if you don’t realize it, you are telling yourself stories. When we teach people that it’s our stories that drive our emotions and not other people’s actions, someone inevitably raises a hand and says, “Wait a minute! I didn’t notice myself telling a story. When that guy laughed at me during my presentation, I just felt angry. The feelings came first; the thoughts came second.”

Storytelling typically happens blindingly fast. When we believe we’re at risk, we tell ourselves a story so quickly that we don’t even know we’re doing it. If you don’t believe this is true, ask yourself whether you always become angry when someone laughs at you. If sometimes you do and sometimes you don’t, then your response isn’t hard-wired. That means something goes on between others laughing and you feeling. In truth, you tell a story. You may not remember it, but you tell a story.

Any set of facts can be used to tell an infinite number of stories. Stories are just that, stories. These explanations could be told in any of thousands of different ways. For instance, Maria could just as easily have decided that Louis didn’t realize she cared so much about the project. She could have concluded that Louis was feeling unimportant and this was a way of showing he was valuable. Or maybe he had been burned in the past because he hadn’t personally seen through every detail of a project. Any of these stories would have fit the facts and would have created very different emotions.

If we take control of our stories, they won’t control us. People who excel at dialogue are able to influence their emotions during crucial conversations. They recognize that while it’s true that at first we are in control of the stories we tell—after all, we do make them up of our own accord—once they’re told, the stories control us. They first control how we feel and then how we act. And as a result, they control the results we get from our crucial conversations.

But it doesn’t have to be this way. We can tell different stories and break the loop. In fact, until we tell different stories, we cannot break the loop.

If you want improved results from your crucial conversations, change the stories you tell yourself—even while you’re in the middle of the fray.