There is a theory which states that if ever anyone discovers exactly what the Universe is for and why it is here, it will instantly disappear and be replaced by something even more bizarre and inexplicable. There is another theory which states that this has already happened.

Dilemmas are all around us. We encounter them in daily life and they are part of every business. In fact, as we live in the globalized world and our societies become more heterogeneous, we are facing more dilemmas now than, say, 50 years ago. Life is less predictable, and we are confronted with more people who have different views. Managers from different generations can be peers in the same company. Different subcultures, each with their own identity, put their mark on the corporate culture. Companies operating in multiple countries have to deal with different national cultures. These can all lead to important dilemmas to deal with.

Functional disciplines each have their own typical dilemmas. For instance, in sales, people often have to weigh the certainty of a small, tactical deal now, versus the opportunity of a more strategic deal later. Or should we sell to a customer directly and keep all the margin, versus selling through a partner, which may lead to reciprocal business, but also leads to lower margins due to partner commissions. Or, more fundamentally, do we focus on value, and advise a customer not to buy a certain high-end product but to go for good-enough, versus focusing on the revenue and trying to upsell to a customer regardless his or her particular need? A typical marketing dilemma would be disassociating yourself from the competition to differentiate, while associating yourself with the competition to have a market. Or consider the world of information technology (IT), where managers and professionals struggle for many years with the dilemma of building systems based on a long-term architectural vision versus quick-and-dirty solutions that provide a tactical return on investment.

Dilemmas are all around us. Harvard Business Review (HBR), the renowned journal for managers and professionals, every month publishes a case study that, while fictional, presents common managerial dilemmas, and offers competing points of view from various experts. The idea is for the reader to make up his or her own mind. These HBR dilemmas are a great sign of the times as they reflect current issues. Some dilemmas are people oriented, and other dilemmas are subject oriented. People-oriented dilemmas deal with human resource (HR) issues, such as taking a promotion that requires a relocation, or hiring a very experienced person versus bringing in some fresh blood. They may also cover leadership issues, such as how to deal with a very friendly and competent manager who drives people crazy by micromanaging. Or they describe moral dilemmas, for instance, what the CEO should do when uncovering evidence about patent fraud involving one of his predecessors.

From a sample of more than 60 issues of HBR over the past few years, about 50% of the dilemmas were people oriented, while 10% were moral dilemmas. The other 40% were subject oriented; they described a difficult strategic choice a leader needed to make. Think of deciding whether you would want to make a private-label product for one of your largest customers, going forward with an acquisition that may have a negative impact on your profitability in the short term, or how to deal with an activist group that criticizes you on the choice of raw materials in your product. Further examination of those case studies reveals that some take place within the organizations, while other dilemmas play between the organization and (one of) its stakeholders, or among stakeholders of the organization—in other words, intraorganizational and interorganizational dilemmas.

People and organizations are not that different.[10] Intraorganizational dilemmas resemble the dilemmas within someone's mind (as introduced in Chapter 1). They represent cognitive dissonance on the organizational level. Interorganizational dilemmas are like the ones between people. The dilemmas people and organizations experience are fundamentally the same. Like personal dilemmas, intraorganizational dilemmas make you examine your motives. Like dilemmas between people, stakeholders with conflicting requirements may put you on the spot. Studying people-oriented and subject-oriented dilemmas, for instance, the case studies described in HBR, forces you to think. And reflecting on the often-conflicting advice of the experts who comment on those cases makes you take a position. But can you predict which dilemmas you will face, based on your strategy?

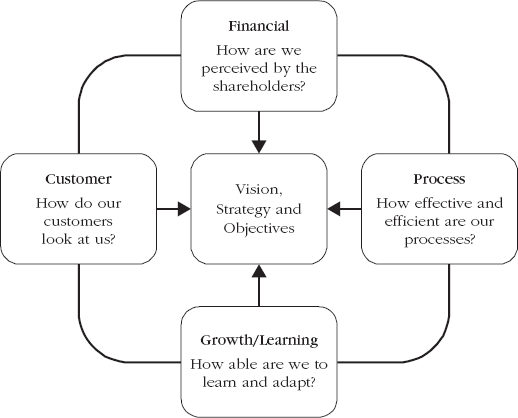

Douglas Adams put it eloquently in this chapter's opening quote: Once you have cracked the problem, something else will come in its place. True as this may be, it does not have to be inexplicable and bizarre. In fact, the strategic dilemmas you will face are quite predictable, using a framework that many organizations already have in place. The balanced Sorecard, developed by Kaplan and Norton, is a framework to describe an organization's strategy and to provide feedback as to its effectiveness.[95] The key message of the balanced Sorecard is that the performance of an organization should be structurally viewed from four perspectives: financial, customer, business process, and learning/growth (see Figure 3.1).

Financial perspective. How are we perceived by our shareholders? Without profits, there is no supply of capital and no sustainable business models. Having sound insight in finance is important for every single economic entity.

Customer perspective. How do our customers look at us? The customer perspective ensures not only that we measure an internal view, but that the metrics also show how the organization is viewed by the customers.

Business process perspective. How effective and efficient are our processes? Processes need to be efficient so that the costs can be managed. Equally important, processes need to be effective so that the customers' needs are served. Proper management of day-to-day operations ensures the short-term health of an organization.

Learning/growth perspective. How able are we to learn and adapt? Investing in human capital (skills), information capital (insight), and organizational capital (ability to change) is necessary in order to be successful in the long-term.

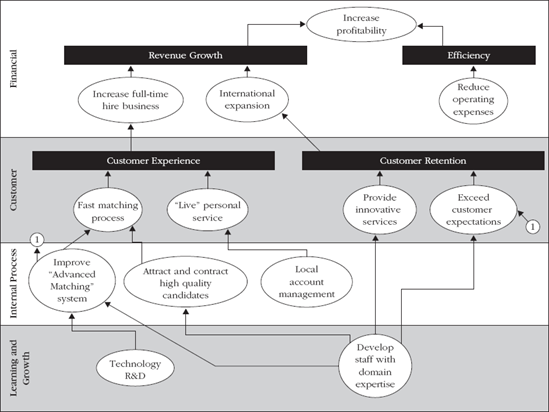

Some even called the balanced Sorecard one of the most influential management concepts of the twentieth century. This might be slightly overstated, but it is clear that the balanced Sorecard has established itself as a core management instrument. According to the Dealing with Dilemmas (DwD) Survey, roughly 70% of respondents indicated the balanced Sorecard is used in their organization. Either it is used elsewhere in the organization (20% of cases), people use it themselves (25% of cases), or it is a company standard (the remaining 25%). Since its inception in 1992, the balanced Sorecard concept has significantly evolved.[96] It started out as a performance measurement system to bring together financial and nonfinancial information in a single report.[11] Quickly, Kaplan and Norton realized there was strategic value in this style of reporting. Limiting yourself on the key performance indicators that drive value creates strategic focus and alignment. Managers throughout the company all know which strategic objectives matter, and how to evaluate the results. The concept of the strategy map turned the balanced Sorecard into a complete framework for implementing and executing strategy—a strategic management system to drive future financial performance. A strategy map is an illustration of an organization's strategy. Its main purposes are to facilitate the translation of strategy into operational terms and to communicate to employees how their jobs relate to the organization's overall objectives.[97] Strategy maps are intended to help organizations focus on their strategies in a comprehensive, yet concise and systematic way.[98]

In the strategy map, the four perspectives, the associated strategic objectives, and the key performance indicators are linked as cause-and-effect relationships[99]. Figure 3.2 shows a stylized strategy map of a fictive company called Tier 1 Talent (also discussed in Chapter 9).

The idea behind the cause-and-effect relationships within the balanced Sorecard describes something fundamental. In order to be successful and have a healthy bottom line, you need to have your shop in order and keep your customers happy. And to make sure it stays that way, you need to adapt to changes in your environment. Conversely, if you do not invest in learning and growth, people will start making mistakes in existing and new processes, upsetting customers, who will stay away and negatively affect the bottom line. In a strategy map, the cause-and-effect relationships depict a one-way, linear approach starting with the "learning and growth" perspective and culminating in financial results. You can argue that if those relationships are linear, the idea of cause-and-effect relationships between strategic objectives is extremely powerful.

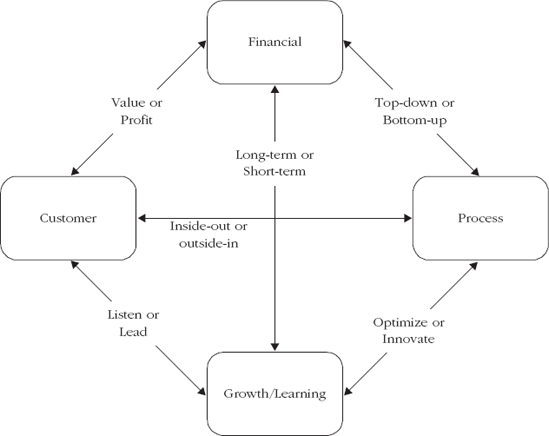

But let us return to the original visualization of the balanced Sorecard, as it reveals an important new insight. Grouping the four perspectives around the strategic objectives, as in Figure 3.1, shows how each of the perspectives not only represents a different angle to business performance, but also poses conflicting requirements. Financial results and the growth and learning perspective live at odds with each other. And optimizing business processes does not necessarily match with a customer orientation. In fact, the perspectives of the balanced Sorecard help in predicting which strategic dilemmas will present themselves in devising, testing, implementing, and evaluating new strategies.

Figure 3.3 shows six dilemmas that can be found in every business:

Value or profit?

Long term or short term?

Top down or bottom up?

Listen or lead?

Inside out or outside in?

Optimize or innovate?

In markets driven by intense competition—and that seems to be the case in most markets today—it is natural to see business as a zero-sum game. In other words, what I win must be your loss. There is only so much market share and market growth, and my share needs to be protected and preferably expanded. Business success is expressed in terms of shareholder value. Market share is based on revenue. Profit is the bottom line, and sales to customers are the means to that goal. Perhaps, at some stages, you may be even busier competing with your competitors than minding the actual driver of performance, looking to serve customers well.

Earlier in this chapter, I discussed a few sales-specific dilemmas that would be very visible here. Do you sell the product that best meets the customer's needs or the one that brings the highest profit? Should you focus on the quarterly results and go for the tactical sale now, or do you develop the relationship and aim for a much larger deal later?

Customers are looking for a good deal, or at least value for money, when considering your products or services. Customers are willing to pay for service. They understand you need to make a fair profit and they may even consider paying a premium for the brand. But your profit maximization is not their goal. Looking back to their early days, most organizations did not have this "profit-versus-value" dilemma. The whole mission of the organization consisted of creating value for the customer. It is when ownership of the business becomes more distant, and shareholder value enters the game, that objectives start to differ and to conflict.

A good test to see how organizations deal with profit versus value is too see how transparent their product specifications and pricing structure really are. Have you ever noticed that on closer examination consumer insurances often have overlapping coverage? Have you ever tried to compare the subscription costs and prices of a mobile telephone provider with its direct competitors? The lack of transparency cannot be a coincidence; it is done on purpose. The prices of some products or services cannot be explained merely by fair profit and brand value. The gap between the price and the value is based on market intransparencies—that is, customers not knowing that the same product or service can be obtained elsewhere at a better price. Lack of information, limited market access, or even price cartels all cause murkiness in the market. Although organizations may profit from that, the profit is not sustainable.[100] Once a competitor pushes for transparency, this becomes a source of competitive advantage.

The good news is that the value-versus-profit dilemma is entirely self-inflicted, by allowing conflicting requirements to distort the business model. A sustainable business model is not based on the idea of a zero-sum game, but is based on win-win situations, in which the dilemma does not even exist. If you truly add value to the business or personal lives of your customers, then profits represent the reward. These profits can be used to invest in additional added value, and the company will be rewarded with additional profits. Business has become a virtuous circle. Profits should be seen as a reward, not as a goal.

A long-term versus short-term focus is one of the most fundamental management dilemmas. From a sales perspective, should you focus on the quarterly results and go for the tactical sale now, or do you develop the relationship and aim for a much larger deal later? From a marketing angle, should you allocate more budget to lead generation or invest in brand awareness? Do you stress more marketing of emerging products, or choose the certain payback of investing in the best-selling products? From a financial perspective, what is an acceptable period to reach return on investment? Short periods create lower return, but more certainty. Longer periods create higher returns, but with higher risks as well. And in the IT world, how much time, money, and effort can be invested in long-term IT architecture versus immediate user benefits?

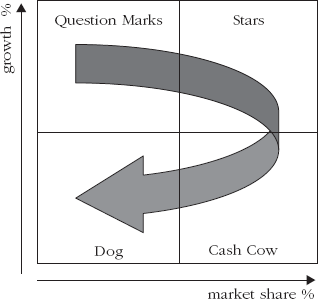

If you do not invest in new approaches, products, and services, at some point, business will dry up. Tomorrow's business will suffer. But if you do not invest in today's performance, there will be no tomorrow's business to worry about. The answer is clear: Choice is not an option here. You simply have to find a way to do both at the same time. Part of the answer is in product lifecycle management. Products and services each have certain stages of maturity. In terms of the Boston Consulting Group (BCG) portfolio matrix, as shown in Figure 3.4, products move from question mark to star, and via cash cow to poor dog. Products and services start off with high growth and low market share, then build market share, then growth slows down, and at the end of the lifecycle market share shrinks as well. Question marks represent strategic options that materialize (or not) over time.

The real dilemma is in how to organize for dealing with the long term versus the short term. Within the standing organization, innovation has a hard time succeeding. The hurdle rate, the standard return on investment the organization is demanding, is too high. Return on investment may be too low, may take too long, or is too uncertain. The overhead of the overall business presses too much on the innovative project and the initial tests that need to be as inexpensive as possible. Standard processes and systems do not allow the innovation team to explore different ways of working. And in general, innovation areas may not be seen as very attractive; the small size of the potential market may not satisfy the growth needs.[101] In many cases, organizations decide to create a new organization around the innovation. IBM did so when developing the personal computer. Most large companies did so when starting their e-business units in the 1990s—nimble, effective businesses, far away from the efficiency-driven main organization. But it should not be a surprise that there is an opposite school of thought as well. Organizations should embrace the concept of creative destruction. This term, introduced by Joseph schumpeter in 1942, describes a "process of industrial mutation that incessantly revolutionizes the economic structure from within, incessantly destroying the old one, incessantly creating a new one."[102] Creative destruction originally described the forces of the market, such as cars replacing horse carriages, downloading music succeeding physical music carriers such as CDs, and e-mail obsoleting fax machines, but the term is sometimes also used to describe how organizations must redesign themselves from top to bottom based on the assumption of discontinuity.[103]

Organizations that have organized in a way that enables them to think for the long and the short term at the same time are often called ambidextrous.[13] How do you develop radical innovations that shape the future of your business, while at the same time protecting your traditional business? Ambidextrous organizations combine the two schools of thought: They create separate businesses under the same roof.[104] Strategy and structure are interdependent. Existing organizations tend to create strategies to protect existing business. New strategies may require new structures, so innovations are put into a new structure. Doing this within the same organization allows business units to share capital, talent, customers, and so on, whereas making them separate business units at the same time allows them to adopt different working styles and have a different culture. Some organizations combine this with the concept of internal venture capital. Emerging businesses within the organization can compete for capital, while top management invests in multiple initiatives to spread risks, creating a portfolio of options.

In the traditional best practices of strategy formulation, strategy is a top-down process. It starts with understanding the market, and how to differentiate to create competitive advantage. Then the optimal strategy can be created, and through a planning process that strategy cascades down into the organization. In the top-down process, the creation of shareholder value is the bottom line. The return on capital employed needs to be as high as possible. One popular way of aligning the organization around shareholder value today is the economic value added (EVA) methodology. EVA aims to capture the true economic profit of an enterprise and to describe creation of shareholder wealth over time. The EVA formula equals net operating profit after taxes (NOPAT) minus the required return times capital invested.[105] EVA explains to business managers on all levels that capital is not for free and should be applied to activities that at least provide a higher return than the cost of capital. Managers are forced to focus on creating value. Business unit plans, investment proposals, and even some projects can be evaluated on their return in the EVA formula as to their contribution to the net operating profit and their expected return. In short, organizations should deploy the initiatives that bring the highest returns.

The opposite view, to create competitive advantage in a bottom-up style, is called the resource-based view of the firm.[106] Resources can be tangible or intangible. Tangible resources include, for instance, access to certain raw materials, as in mining industries. Or think of labor that is particularly skilled, or resides in low-cost countries. Capital is an important resource as well, as are facilities that are needed to produce products and buildings. But in today's globalized economy, intangible resources are perhaps a more deciding factor in gaining competitive advantage. Intangible resources can include specific knowledge, perhaps protected by patents. Or think of having access to certain distribution channels and market segments through partnerships, or a database with consumer information. Cultural attributes such as organizational resilience, perseverance, and entrepreneurialism are resources you can draw from as well. Resources need to be valuable, rare, inimitable, and non-substitutable (VRIN). If you single out any one resource, it might not pass all elements of the VRIN test. A collection of tangible and particularly intangible resources, however, may be a solid basis for a differentiating strategy.

In the top-down approach, the financial results are leading. Based on the desired outcomes, the organization needs to look for and deploy the resources that are needed to fulfill those requirements. The opposite approach, bottom up, takes the resources as the starting point and aims to maximize the output.

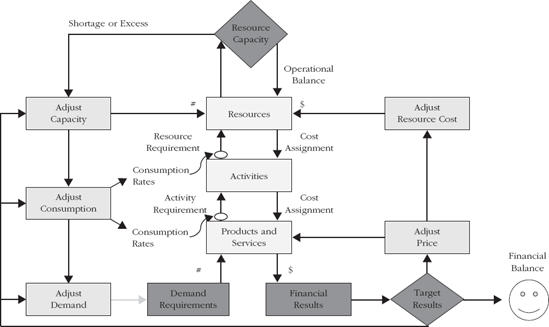

To be successful, the bottom-up and top-down approaches need to be fused. Strategy as a learning process is about continuously tweaking the alignment between resources and financial outcomes. The more you can invest in dynamic capabilities and resources, being able to reconfigure the use of resources, the more effective this process of alignment can be. Figure 3.5 shows the levers in this process of alignment.[107]

The objective of continuously aligning resources and financial results is a sustainable, profitable business. Financial results are achieved by selling products and services that are produced through certain activities. Activities in turn are fueled by resources. If the products and services are not providing the right results, on the financial side you can either adjust the price (increasing it for a higher margin, or decreasing it for lower margins but higher turnover), or adjust the resource cost by renegotiating contracts or switching to a supplier that delivers the same for a lower price. But not all controls are price related. If the demand requirements change, the right amount of increase or decrease of resources may be needed. A deep insight into the relationship between products, activities, and resources means that the right resource can be adjusted by the right amount (adding, for instance, a new machine, or a new hire). Alternatively, the resource consumption can be changed. Perhaps it is possible to use people's time more efficiently. Or maybe a new product design reduces the number of parts, leading to a lower cost and a speedier production process. Further, demand can be influenced by marketing, as in a "buy two, get one free" campaign.

Both the top-down and bottom-up approaches try to achieve the same thing: to prevent local optimizations. In a bottom-up approach, the decentralized resources are aligned with the corporate goals, and the goal is to contribute as much as you can. From a top-down point of view, the centralized goals are the starting point. Many organizations continuously struggle with the balance between centralization and decentralization.

Larger organizations have a natural tension between the front office and the back office. The front office represents most customer-facing activities, such as sales, service, and large parts of marketing. The back office represents administration, manufacturing, or other types of production, procurement, logistics, and support functions such as Finance, Legal, and Human Resources. The front office, being market driven, is looking for ways to cater to the specific needs of customers. "There is always an opportunity to jump on, if only the back office would understand," they say. The back office has an eye on standardization, looking for ways to create a lean-and-mean operation. "There simply must be some rules to comply with, if the front office would only grasp that," they argue. In short, the front office has an outside-in approach, whereas the back office works from the inside out. There are different angles to this dilemma. Flexibility is battling with scalability; agility is at odds with manageability. In short, the need for both effectiveness and efficiency may pose conflicting requirements.

In entrepreneurial organizations, the front office clearly has the lead. Senior management adopts first-mover strategies to beat the competition. There is always an opportunity. Business is operating at the bleeding edge. The complete organization is built around agility, the ability to respond quickly to change in the market. The company is willing to make big bets, and if they turn out to be the wrong ones, the decision is reversed and the company changes course. These outside-in-driven organizations can be extremely effective, but are usually not very efficient. The back office has to "pick up the pieces," and needs to make significant investments in reorganizations, business processes, and IT systems to do so.

In more bureaucratic environments, the back office has the lead. The strategy is about economies of ale, standardization, and cost control. New ideas tend to focus on more efficient ways to do business. The business is a master in adopting and fine-tuning best practices. As a competitive strategy, the firm is not particularly nimble, but may have a good level of absorption.[108] Its lean-and-mean structure can endure good and bad times, and when the time is right, it will strike and claim its market share. The inside-out-driven organization is very efficient, manageable, and Salable, but, as a side effect, not very flexible. Sometimes it seems the most important job of salespeople is to explain to customers the ordering process, and Legal is nicknamed the "sales-prevention department."

Of course, these are black-and-white caricatures. In fact, organizations may find it surprisingly hard to tell "who is in charge." Is sales selling what manufacturing has produced, or is manufacturing producing what sales has sold?

Common belief says you should not address this dilemma at all; instead you should nurture it. Organizations need to be both effective and efficient. Equally strong back-office and front-office forces may keep the company balanced. However, technology innovation has at least moved the border for this dilemma. Many business models have adopted mass customization principles, where every single transaction can be tailored to the customer's specific needs. Consider the pharmaceutical industry's move toward personalized medicine, the configuration options car makers offer buyers, and commercial web sites offering personalized homepages. These business models are often self-service in nature. The customer-order-decoupling point[14] has shifted dramatically. Customers can compose their own insurance or mortgage based on financial components, check themselves in for a flight via the Internet, and make changes to the configuration of their PC minutes before it gets produced. In processes like this, where does the front office stop and the back office start? There is no difference anymore. Both back office and front office contribute equally to the customer experience. Real-time monitoring has changed the dynamics in the value chain. The value chain can be supply driven (inside out) based on iron discipline in product delivery, and event driven (outside in) based on a good grasp on inventory turnover, at the same time.

The production dilemma[109] is foundational to manufacturing environments, and has become very apparent in administrative processes as well. Some refer to it as exploration versus exploitation, where exploration includes things captured by terms such as search, variation, risk taking, experimentation, play, flexibility, discovery, innovation. Exploitation includes such things as refinement, choice, production, efficiency, selection, implementation, and execution.[110] Exploration enables the creation of new knowledge, whereas exploitation supports the refinement and use of existing knowledge.[111] In the context of strategic dilemmas, I prefer to use a more generic description: optimization versus innovation. Optimization means tailoring an environment toward a specific goal. All waste must be eliminated. Waste would be defined as everything not directly contributing to reaching that goal. But what happens when the goal changes? Was all the waste that was eliminated really waste? Or did we throw the baby out with the bathwater and lose all the capabilities to be agile and change the process as well? Some organizations complain that they have become so good at efficiency, they cannot innovate anymore. The bias toward optimization is logical. There is less risk involved, the returns are realized in the short term, and the gains are relatively easy to measure. The disadvantage is too much focus on internal control, and losing sight of the changes in the market. And the more you optimize toward a certain goal, the more you hardwire your processes toward that particular goal. The question is whether the efficiency gains outweigh the (potential) costs of change.

This does not mean that manufacturing environments have no attention for change. In fact, the dominant school of thought in this field, called lean,[112] counts on continuous improvement as one of its corner pillars. The best-known method for that is Six Sigma,[113] which utilizes data and statistical analysis to measure and improve a company's operational performance, practices, and systems. Six Sigma identifies and prevents defects in manufacturing and service-related processes, and represents a measure of quality that strives for near perfection. Sigma (the lowercase Greek letter σ) is used to represent the standard deviation (a measure of variation) of a statistical population. The phrase six-sigma process means that if you measure six times the standard deviation between the mean outcome of the process and the nearest critical threshold, there is a minimal chance of failure. Six Sigma is not a project, but a process aimed at continuous improvement. Processes are continuously monitored, analyzed, improved, and controlled to ensure that any deviations from target are corrected before they result in defects. There is continuous improvement, indeed, but within the existing paradigm prescribed by the strategic objectives, instead of improvement toward facilitating change based on new goals.

The Toyota Production System (TPS) is geared towards mastering the dilemma between optimization and innovation. The company actually succeeds because it creates contradictions within the organization.[114] Employees on all levels need to constantly grapple with challenges, and must come up with fresh ideas. For many years, Toyota moved slowly, expanding production capacity only step-by-step, yet making big leaps forward, such as with the Prius, a revolutionary hybrid engine[15]. Toyota is known to be a very cost-conscious organization, like IKEA or Wal-Mart, but is equally known for investing heavily in manufacturing facilities, dealer networks, and human resources. Finally, Toyota is a very hierarchical company, but has a culture in which strong and candid pushback is encouraged.

Many have commented that the innovation versus optimization dilemma is eternal. You cannot optimize and innovate at the same time; the forces each push in a different direction. However, as I argued in Chapter 2, when discussing emerging strategies, there is interaction between established daily routines and new situations. The combination is an important source of learning, as hitting a transaction or activity that the process cannot cope with represents the first moment a new phenomenon or a change in the market is experienced. What would happen if you deliberately allow or bring perturbation, disturbance, or confusion[115] into processes, such as ambiguous goals, errors, or strange requests? This would shake things up, and force managers and processes to deal with discontinuity. Little shakeups take a process into unknown territory, where no precedents exist to guide organizational action. No one knows for certain what process should be executed next. Shakeups can be accidental, the kinds the organization did not seek and did nothing to prompt. Think of natural disasters. At the other end of the spectrum there is induced confusion, purposefully provoked by the organization, for instance, to conduct experiments. Induced or accidental, the key to reconciling optimization and innovation is how you deal with those shakeups and turn them into additional options for the process to address.

What are you looking for from your customers? By doing good business, you hope they bring you profit and growth. You hope they trust you, so they come back for more business. But you would also be interested in their opinion, to make sure you are on the right path with your innovations. Conversely, customers are looking for products and services that fit their needs. These need to be reasonably priced. Interactions with the supplier need to be fast and it should be easy to do business.[16]

It is interesting to see that in this list of customer requirements, there is no such thing as innovation. Typically, if at all, customers express their opinion on current needs, not their future needs. Innovation does take place; things move in an evolutionary way. The moment a customer needs change, products and services evolve with those changing needs. It is vital to stay in touch with market demand; otherwise, a business loses its relevance.

But breakthroughs rarely come from listening to customers. Who ever asked for e-mail, spreadsheets, or the Nintendo Wii? Did anyone express the need for matches or a lighter? And what about options such as power steering and park distance control in your car? Or soda drinks, the telephone, Monopoly (the game), collector soccer cards, roller-skates, or the paper clip? Someone simply came up with them, and—after perhaps a few generations of product improvement—this created a new need and demand altogether. Successful breakthrough innovation comes from leading your customers.

Both listening and leading are needed, in order to protect both current business and new business over time. There are multiple ways to connecting listening and leading.

No one says you need to have a single strategy for the complete organization, that constraint is caused only by taking too much of a classical top-down approach to strategy. Different business units need different strategies. Think of a construction company, offering both prefab houses and bespoke construction work. In the prefab housing business, it may make sense to listen to your customers. Profit comes from reselling a certain model many times, and there are certain trends that everyone seems to like in a certain timeframe. Customers see finished products and in their buying decision judge whether they like it. Being well in touch with customer perception is a good recipe for success. In offering bespoke construction work, the construction company is the expert, knowing specific regulations and the right constructions. Specific customer requirements may not be practical, or may lead to excessive cost. It is important to provide your expert opinion—in other words, to lead the customer.

However, there is a time where one of the approaches is more important than others. In times of paradigm shift, leading the customer is more important. In the IT world, that would be the shift toward service-oriented architectures. In the automotive industry, that would be the switch from gasoline-driven cars to electric cars or cars driving on hydrogen fuel cells. In the telecom industry, providers have been switching from gsm to "third generation," experimenting with umts, gprs, hsdpa, edge, and other standards. The idea of switching modes, from stability and continuity to disruption and change—and back again—is a premise of a strategic management school of thought called configuration. Strategy is a process of configuring the organization, its resources and processes and other important elements, and reconfiguring them if the market evolves or the organization itself matures. The goal is to sustain stability most of the time, but periodically to recognize the need for transformation, and to be able to manage that disruptive change without destroying the organization.[116]

In the true spirit of synthesis, you can also try to fuse both leading and listening. You could be the leader in listening to customers, picking up signals before your competition does, and extrapolating what you learn far beyond the customer's own imagination. For instance, chip manufacturer Intel made use of ethnographic research techniques.[117] By directly observing households, researchers created a better understanding of how people are making use of technology in their daily lives. By observing obstacles in using technology, or by discovering practical but unintended uses of technology, Intel can create products that serve the customer needs in a better and innovative way. And by using techniques that create a much deeper insight than traditional market and consumer research, Intel positions itself as a leader in the market.

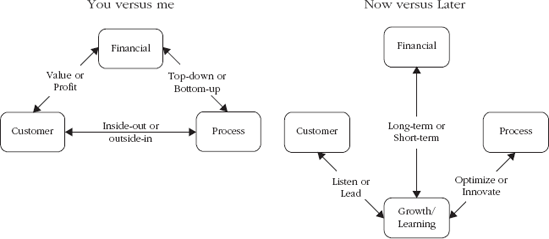

On closer examination, the dilemmas that we have examined both within the organization and between organizations can be classified in two types: the ones that highlight conflicts between parties (you versus me) and the ones that separate the long term from the short term (now versus later). Figure 3.6 shows an overview of how to classify the dilemmas.

Each type of dilemma has its own way of being addressed. You-versus-me dilemmas require synthesis, looking not for what divides the conflicting sides, but for what binds them. Organizations that take a stakeholder approach seek to add value to their stakeholders as a means to maximize profit, and profits are a means to create stakeholder value. Organizations that have broken down the walls between the front office and the back office have raised the bar on customer experience. The back office is even more efficient while customers do part of the work in a self-service business model, and the front office has the benefit of higher customer satisfaction. Organizations that have aligned a top-down financial focus with a bottom-up resource-based view of the firm have overcome the dilemma. Every change in both financial means and operational resources and activities can immediately be translated into an overall new picture. The complete value chain is optimized instead of each functional domain in itself. In terms of Jim Collins, you-versus-me dilemmas benefit from having the genius of the and.

Now-versus-later dilemmas require a different approach. They are about creating options. It means making sure that whatever the future brings, you can flexibly deal with it and still reach your goals. Organizations need to be ambidextrous in nature, minding both the short and the long term at the same time. With only a long-term view, the organization might not actually realize its long-term vision, while short-termism alone endangers future success. Fueling innovation creates future options. Although listen or lead certainly has you-or-me aspects, it is mainly a now-versus-later dilemma. Listening to customers is important in times of evolution, when once in a while strategies need to be reconfigured and taking the lead to reach a new level is required. Taking the lead opens up new doors and new options. Finally, optimize versus innovate can be addressed by creating confusion and ambiguity. If people can handle this, they will be able to handle unplanned shakeups as well. Their toolkit is able to handle more options than a hardwired and optimized process.

Now that we understand how to recognize the typical strategic dilemmas, and we understand that there are ways of dealing with them, they are not that scary, anymore. With that concern taken away, now is the time for a self-assessment.

[10] Both are living organisms (A. de Geus, The Living Organization: Habits for Survival in a Turbulent Business Environment, Longview Publishing, 1997). Like people, organizations are born, grow up, and die. Some barely grow up; they die young and irresponsible. Other organizations mature and grow old and wise. Over time, organizations expand and sometimes contract, like people who gain weight and diet when necessary. Organizations, like people, create children in the shape of new activities and business units that sometimes spin off into other activities and units. People can understand who they are only by understanding their place in society. Equally, organizations do not operate as islands; they interact with their stakeholder environment all the time. They affect their environment and their environment affects their behavior. Organizations have a responsibility toward their environment. Organizations build partnerships and alliances, just as people have friends. Some of these relationships last a long time and cross various phases in the organization's existence; some belong specifically to a particular phase in time, as friendships do.

[11] I was not in the room during the workshops that led to defining the four perspectives, but I have a hypothesis as to how it could have happened. In figuring out which nonfinancial areas to pick, someone may have mentioned the three value disciplines from Treacy and Wiersema that I described in Chapter 2: operational excellence, product innovation, and customer intimacy. These map process, growth/learning (innovation), and customer exactly. The fourth perspective had to be the financial outcome. From this point of view, you could see the first version of the balanced scorecard as a first attempt to solve strategic dilemmas—to see how to balance all. If it did not happen this way, at least it shows the logic of the four perspectives, as they align with other established management theory.

[13] Ambidextrous means being equally skillful with both the left and right hand. For instance, an ambidextrous tennis player can always play a forehand. In the context of business, unfortunately, nowhere is it clear whether the left hand stands for long term and the right hand for short term, or vice versa.

[14] The customer-order-decoupling point is the moment in a process where customers can no longer make any changes in specifications. For instance, in terms of producing an automobile, specifying the color can be done at any time from the moment the order is submitted, to seconds before the actual moment of painting the nearly finished car.

[15] It seems this touches the core of the problem that Toyota experienced with its 2010 recalls. It can be traced back to the principles of TPS. Part of the success also was the slow but steady speed of growth. When Toyota worked towards the goal of becoming the largest car manufacturer in the world, it found out (the hard way) that growth was a constraint in its formula for success. Another dilemma emerged, growth versus stability. Given Toyota's ability to handle the optimization versus innovation dilemma so far, I have all the faith it will find a way to deal with growth versus stability as well.

[16] This list of customer contributions and requirements is drawn from a methodology called Performance Prism, which will be further discussed in Chapter 10.