No man was ever so much deceived by another as by himself.

Improvement is driven by three questions: Where am I now, where do I want to be, and how do I get there? So if we want to improve the way we deal with dilemmas, we should start with a self-assessment. A true assessment requires reflection, the ability to take a hard and honest look at your organization, and not kid yourself. Moving from an either/or approach to an and/and attitude requires deep understanding not only of the organization's strengths, but also its weaknesses.

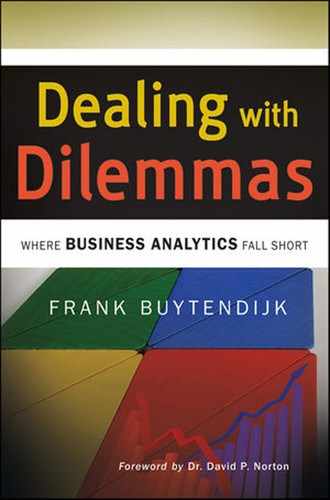

The Global Dealing with Dilemmas Survey (DwD survey) reveals the self-assessment of 580 respondents from 55 countries (see Figure 4.1). The majority of responses came from commercial companies, although 9% of respondents represented public sector organizations. The three most prominent sectors in the survey were professional services, high technology, and financial services. However, almost every other industry was represented, too, such as telecom, oil and gas, retail, aerospace, pharmaceuticals, automotive, and utilities.

These self-assessments were collected during interviews, workshops, presentations, and through a web survey. In the survey, I asked respondents to score themselves and their organizations on a number of things. I asked how well they think they deal with strategic dilemmas, and then asked a number of questions to verify that self-assessment. I also inquired as to what extent respondents were familiar with a number of management methodologies, and asked them questions on how they would solve particular dilemmas.

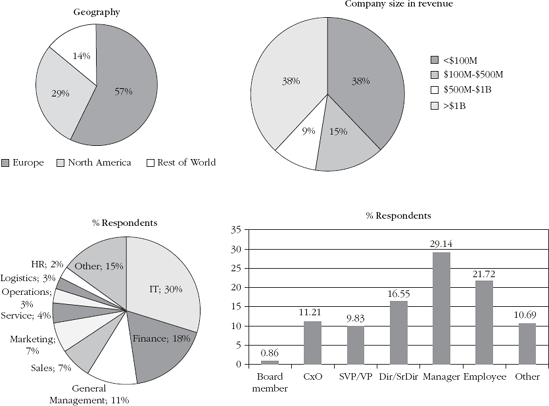

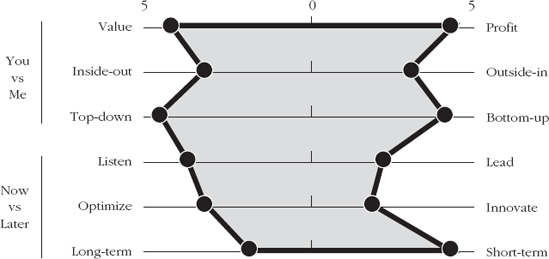

I have found a total of five possible "states" an organization can be in when assessing its capability of handling the six fundamental dilemmas defined in Chapter 3: (1 and 2) Organizations can have a strategic bias (to one side of the spectrum or to the opposite side); (3) they can have a neutralview; (4) they can be strategically stuck; or (5) they can have achieved strategic stretch (see Figure 4.2).

In many cases organizations will have a strategic bias. This means that they typically approach a dilemma from one side. For instance, they tend to be more inside-out driven than outside in, which means that the needs of the back office usually come first. Customer processes are defined to satisfy the back office first. Or their bias goes the other way: The front office is always in the lead, and it is the task of the back office to make it all work. This strategic bias, to one side or the other, can appear in each business dilemma. You have an either/or attitude, and it is usually either that is chosen. The consequences can be predicted, the need for addressing the opposite side is clear, but it takes the organization out of its comfort zone. It takes extraordinary effort to deal with issues caused by the other side of the dilemma.

If you score neither high nor low on both sides of the dilemma, you are operating in the neutral zone. You deal with the dilemma by looking for a trade-off; you are trying to strike a balance or find a reasonable compromise. You optimize processes a little, and once in a while, within the existing processes, you consider how you can incrementally improve and innovate. Or, as another example, you make sure you are profitable, but do not try to maximize profitability, as that would be at the expense of the value you deliver to customers. In essence, there is nothing wrong with this state, as long as it is in an area where you feel you do not have to differentiate from the competition. Simply seeking a compromise between two opposites requires the least management attention, and it can be a sustainable state.

If you score low on both sides of the dilemma, this means you are strategically stuck. You are good in neither one nor the other side of the dilemma. You do not listen and you do not lead. You do not optimize and do not innovate. You neither plan for the long term, nor are successful managing the short term. It seems every problem you encounter takes you out of your comfort zone. This, of course, is an undesirable situation, whether it is a strategic dilemma or not. Being strategically stuck is a strong wakeup call. In areas where you should have competitive differentiation, your competition is probably already overtaking you. And in areas that are not strategically important, you are simply not very efficient, draining resources that could be better used elsewhere.

If you score high on both sides of the dilemma, you have found a way to reconcile both sides of it, through synthesis. You have achieved strategic stretch. You have found a way to listen and lead, for instance, by leading the competition in being a better listener to customers, or—the other way around—involving customers heavily in groundbreaking innovation. You have found a way of maximizing profits, because you offer the most value to customers. Or you know how every short-term decision and tactical program contributes to the long-term strategic objectives. For dilemmas you deem crucial in your business, this is the desired state where you have found "the genius of the and."

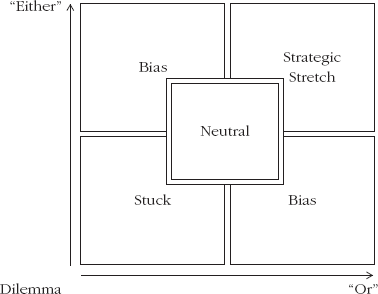

A good way to visualize how you are doing with the six dilemmas is to create what I call a strategy elastic.[17] Creating strategic stretch is very much like working with an elastic band. If you pull it from only one side, the other side will move along in the same direction. You can stretch it only if you pull it from both sides. And the harder you pull in multiple directions at the same time, the more space you create, which is the objective of strategic management. The metaphor of an elastic band is particularly appropriate because it implies you cannot stop pulling; otherwise, the elastic band goes back to its neutral position. Strategy management is the same. You need to keep working on creating strategic stretch—otherwise, the organization will fall back to average results. Execution is a continuous process.

Consider the strategy elastic of a U.S.-based media and entertainment company[18] with over $1 billion in revenue, as shown in Figure 4.3. Its results are not extreme, but they do tell an interesting story. The one thing the company is good at is the listen-and-lead dilemma. It has found a way to innovate beyond direct customer requirements, while at the same time listening to customers very well. The company does so by spotting trends, even before the customers have spotted them. However, the company has mostly a short-term focus. It probably jumps from one trend to another. This is not very good for creating a long-term vision. As a media and entertainment company, it is very much focused at translating trends into new products and pushing those products out. There is a bias toward inside-out thinking. The company scores slightly below neutral, and toward being strategically stuck on the top-versus-bottom and the optimize-versus-innovate dilemmas. It does not pay a lot of attention to processes, and alignment is a problem as well. It seems margins are relatively high in this market, as the company can afford to be in the neutral zone, trading off customer value and profitability.

Let us look at a small financial services firm, based in Western Europe. Its strategy elastic is shown in Figure 4.4. Perhaps it is the economy (the survey was held during the latter part of 2009), but the short-term focus on the company is relatively extreme. However, the focus and alignment in this company is very high. The strategic objectives of the company (top down) are known to everyone, and it is clear to everyone how their daily work contributes to those strategic objectives. The alignment between creating customer value while maximizing profitability is also remarkable. For a small financial institution, such as an up scale private bank, this actually should be the basis of the business model—having transparent fees and commissions, while increasing the wealth of its customers. As a small organization, it does not pay a lot of attention to its processes. It borders on being strategically stuck here. It is probable that the optimization that takes place is based on regulations and compliance. The products that the firm offers are not particularly innovative, but the company distinguishes itself by being close to its customers. Its strategic bias here is clear.

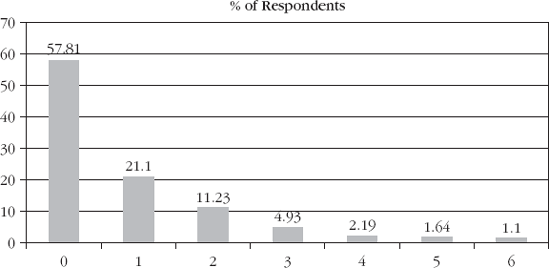

Being able to reach strategic stretch on a certain dilemma is not a trivial thing. More than half of the respondents in the DwD survey do not score any strategic stretch across the six dilemmas. Only 20% of respondents achieve strategic stretch on one dilemma, and less than 5% are able to stretch on three dilemmas.[19] Figure 4.5 shows the overall distribution. Although strategic stretch is a good thing, and organizations should work toward strategic stretch on as many dilemmas as they can manage, it is not necessary to score stretch on all dilemmas. It takes energy to stretch an elastic, and once you stop, it goes back to its old shape. Organizations do not have the energy to be perfect on all fronts. It is better to choose which dilemmas contribute most to the organization's competitive profile and focus on those.

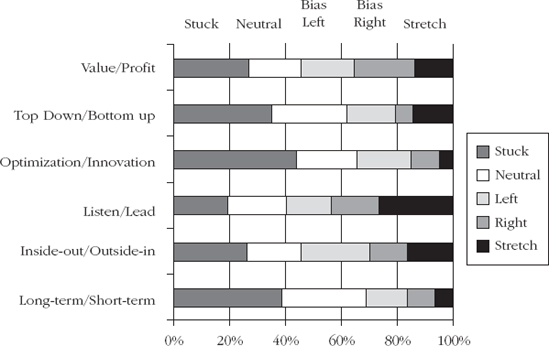

Each company has its own profile. In fact, the survey data did not suggest there were profiles that were significantly more common than others. However, when examining how organizations are doing on the level of individual dilemmas, a clear pattern emerges. Not all dilemmas are equal. Figure 4.6 shows which dilemmas are more prominent than others.

Some dilemmas are harder to deal with than others. Close to 40% of all respondents state they are strategically stuck in the long-term-versus-short-term dilemma, and over 40% of all respondents feel the same about innovation versus optimization. Even if you look at the companies that score very high (the top 4% that stretch four or five dilemmas), it is typically long term versus short term and innovation versus optimization that score the lowest. These two dilemmas seem to be the two thorniest ones. Chapter 9 extensively addresses long-term versus short-term dilemmas, discussing options-based strategies and scenario planning.

The biggest area of strategic bias can be found in the value-versus-profit dilemma. Some organizations focus on the customer, following the philosophy that profits follow as a logical consequence. But this is not always true. Most customer profitability analyses show that a certain percentage of large and respected customers are simply not profitable. Having large account teams, offering quantity discounts, and other measures to keep and grow large customers also add to the cost of sales, which is not always considered in the customer relationship. However, more organizations have a strategic bias for the profit side, even to the detriment of providing customer value. This cannot be a sustainable situation for the long term. At one point, customers will find out or will find alternatives, and will defect.

Listen and lead is the dilemma that organizations have mastered most. Around 25% of respondents report they have a strategic stretch. The U.S.-based media and entertainment company reported strategic stretch on this front. Leading customers with innovation is usually called product innovation, whereas listening to customers is called customer intimacy. As discussed in Chapter 2, traditional strategic management advocates that you have to choose. However, most companies report that they do both equally well.

If you break down the scores into three buckets, the 33% worst-scoring companies, the 33% average-scoring ones, and the 33% best-scoring ones, some very interesting conclusions emerge.

Those that are at the bottom one-third, and are stuck or neutral in four or five of the dilemmas, are much more likely to have a bias toward value, leading customers, and preferring an outside-in approach. These are the three biases connected to the customer perspective in the balanced scorecard. What this means is that "putting the customer first" is not automatically the right thing to do. The key to success is to reconcile both customer focus and a focus on your own strategic objectives.

Organizations with average scores and that are neutral or stuck in three or four dilemmas tend to have a bias for inside-out thinking and leading the customer, and a profit orientation. These are the companies that are driven from the inside, with a focus on their own objectives. They change when needed by absorbing it, but do not really drive change.

In the top one-third of companies, which score stuck or neutral in two dilemmas or less, where they score a bias, it seems to be toward innovation, a long-term view, and an outside-in approach. These are largely connected with the growth/learning perspective—worrying about tomorrow's performance. This seems to be a good starting point for getting strategic stretch all over.

A quick way to get your own strategy elastic self-assessment started is scoring your organization on the questions in Table 4.1. If you decide to use the survey for others within your organization, I recommend that you randomize the order of the questions. This way the structure of the six dilemmas does not reveal itself so easily, which would otherwise bias the answers.

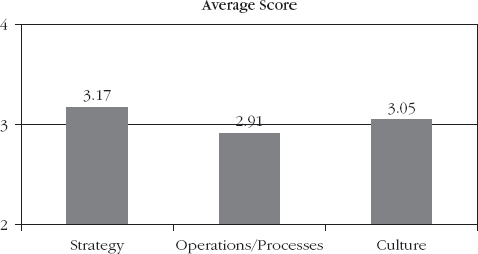

A score of 1 means you tend to disregard the subject; scoring a 3 means you do an average job, nothing spectacular. If you score yourself a 5, that means you consider your organization to excel in that respect and it constitutes a strategic differentiator. For each side of the dilemma, there are three questions. One question is about the strategy of your organization (S). Another question deals with operational aspects, such as processes, methodologies, and measures of success (O). The third question addresses cultural aspects (C). In case the specific question does not relate to the reality of your business, answer in the spirit of the question.

Table 4.1. Assessing Your Strategy Elastic

Create Your Strategy Elastic | |

|---|---|

Value S1: Do you involve key external stakeholders, other than investors (such as partners and customers) in making strategic decisions? O1: To what extent do you hire sales representatives who are long-term relationship builders, and measure customer satisfaction and repeat business? C1: When making decisions, to what extent does your organization truly focus on what is best for the customer? Average score: | Profit S7: Is the creation of shareholder value central to strategic decision making? O7: To what extent do you hire sales representatives who hunt until they close a deal, and then measure them on revenue? C7: When making decisions, does your company focus mostly on the question "What is in it for us? Average score: |

Inside Out S2: To what extent can your strategy be characterized as "focusing on the core business"? O2: How would you score the quality of your product marketing? C2: To what extent can your culture be described as seeking conformity and consensus throughout the organization? Average score: | Outside In S8: To what extent does the organization know how to recognize sudden new opportunities in the market and seize them? O8: How would you rate the quality of your relationship marketing? C8: To what extent are employees encouraged to behave entrepreneurially, for instance, being empowered to make immediate decisions? Average score: |

Top Down S3: When there is a strategic change, to what extent can you translate new financial goals into updated operational plans? O3: Are most people in your organization informed about financial performance indicators, such as profit, cost, and EVA? C3: Do you and your colleagues know exactly what top management expects from you? Average score: | Bottom Up S9: To what extent can you measure the financial impact of changes in operational company resources (capital, people, systems, materials)? O9: Are operational performance indicators, such as production, waste, speed, and quality, shared broadly in your company? C9: Do you know exactly what your colleagues in other business domains expect from you, and vice versa? Average score: |

Listen S4: To what extent is your strategy based on being very close to the needs of your customer, in other words, "customer intimacy "? O4: To what extent is your organization structured around customer interaction processes and channels? C4: To what extent is your organization looking to jump on the bandwagon of new customer trends? Average score: | Lead S10: To what extent is your strategy based on product or service innovation to differentiate from the competition? O10: To what extent is your organization structured around the products you produce and sell? C10: To what extent is your organization always on the forefront in setting new trends? Average score: |

Optimize S5: Do you agree with the following statement: "For us, innovation and improvement is a process of continuously taking small steps forward"? O5: Have you embraced lean, Six Sigma, or related concepts? C5: Are the people who drill down into issues deeper than anyone else seen as the "heroes "in your organization? Average score: | Innovate S11: Do you agree with the following statement: "For us, innovation is about making dramatic moves in the market, like large acquisitions or revolutionary new products and services"? O11: How would you characterize reorganization processes in your organization? C11: Are "out-of-the-box "thinkers recognized most in your organization? Average score: |

Long Term S6: Is it clear to all employees what the long-term vision of the organization is and the road ahead? O6: How would you rate your product lifecycle management? C6: Does your organization agree with the statement: "You need to fix the roof during summer" (meaning, reorganize and save money when times are still good, to be able to weather bad times)? Average score: | Short Term S12: To what extent is it clear to every-one how and how much their daily activities contribute to the everyday success of the company? O12: How would you rate your level of insight into customer and product profitability? C12: Does your organization agree with the statement: "We will cross that bridge when we get there" (meaning, better to wait until bad times are here and we understand them, so we can take the appropriate action to save cost and reorganize)? Average score: |

With these scores, you can plot your strategy elastic, and discover your strategic biases, strategic stretch, and where you are strategically stuck. Particularly in areas where you score only average, it is important to look at the distribution of the three scores. You may, for instance, score high on strategy, but low on culture. This result may indicate a misalignment in your organization, and probably a continuous source of struggle.

We can distinguish the following types of misalignment:

If you score high on strategy, but not on the others, you may have an execution issue in the organization. You have the right ideas, but somehow they do not make it to the execution phase, or it is hard to cascade them down into the organization.

If you score high on operations/processes, but not on the others, the organization probably is "cruising." Your organization is ready for it, but the right ideas are not coming, and if the right ideas are there, the people in the organization do not have the passion or drive to make a change. It means you are vulnerable in economically stressful times.

If you score high on culture, but not on the others, there is certainly intent and ingredients for success, but they are not pulled together. The organization is a hotbed for talent, but it is not turned into results. Most likely, staff turnover, particularly among the high potentials, is high. At first, people are enthused by the vibes in the organization, but they get disappointed quickly, as nothing really happens. Some very innovative organizations are actually known for this. They provide the basis of many inventions, but others turn them into profitable businesses.

The DwD survey shows that on average organizations score the weakest in the area of operations and processes (see Figure 4.7). This confirms most of the research that states that strategy execution usually is the weakest link. Ninety percent of well-formulated strategies fail in the execution. It also highlights an important shortcoming in traditional strategic thinking that separates strategy formulation, strategy implementation and execution, and strategy feedback. Making strategy a continuous process puts execution at the center of successful strategy management. Conversely, the results show that the organizations that score well on the operations-related questions also do well on the strategic and cultural level.

Table 4.2. Strategy Elastic for South African Education and Research Organization

Strategic | Operational | Cultural | |

|---|---|---|---|

Value/profit | Stuck | profit-bias | Neutral |

Top/Bottom | Stuck | Stuck | Neutral |

Optimization/Innovation | Opt. bias | Stuck | Neutral |

Listen/Lead | Stuck | Neutral | Listen bias |

Inside Out/Outside In | Neutral | Stretch | Outside-in bias |

Long Term/Short Term | Short-term bias | Stuck | Long-term bias |

The area where you score high, for instance, on the cultural level, may be a good starting point to improve scores in the other areas as well, like strategy and operations.

Let us analyze a few examples from the DwD survey, looking at their specific scores for strategy, operations, and culture. Take, for instance, this education and research organization in South Africa that seems to be experiencing some issues. Its strategy elastic looks like Table 4.2.

As with so many academic cultures, the staff has a strong long-term focus, and an entirely different sense of urgency compared to the management of the organization. No wonder the organization is stuck in a number of places. Management and staff are on completely different paths. As a result, it is stuck between delivering value in the form of excellent research and education, and a healthy financial bottom line. There is definitely no alignment in the organization—it is strategically stuck in the top-versus-bottom dilemma. However, this organization is mostly on the operational level. Given that for half the dilemmas the organization reports being stuck on the operational level, it seems the organization and its processes need to be fixed. There is passion in the culture, but not for the dilemmas that are aimed at running an efficient organization. The staff cares deeply for listening to its customers, taking an outside-in approach, and minding the long term. The staff's culture is fairly neutral toward issues of management in the first three dilemmas in the table. Organizational change may not be resisted too much, which means there is hope for this organization.

Or consider this mid-sized Western European manufacturer, as shown in Table 4.3. It must be very frustrating for the people working there because although they have a strong bias for innovation, the management is mainly concerned with optimizing current operations. New ideas do not get a chance on the strategic level. Even worse, there is a strong entrepreneurial spirit, but management is more interested in simply running the core business. As a result, the company is stuck or at best scoring neutral on all dilemmas from an operational point of view. It is no wonder, with such misalignment between culture and strategy.

With an assessment of current results on the table, and your own strategy elastic defined, the next logical question is: How do we create strategic stretch for the dilemmas that matter most to us? Different dilemmas need different approaches. Now-or-later dilemmas benefit most from creating a portfolio of options, whereas you-or-me dilemmas should be addressed by seeking synthesis. The concept of synthesis was introduced in Chapter 1, and defining the goal of strategy management as creating a portfolio of options was the subject of Chapter 2. I will address techniques for creating such a portfolio and how to achieve synthesis in the chapters ahead.

[17] Strategy Elastic™ is trademarked by Frank Buytendijk

[18] All survey entries were anonymous. I only asked only for industry, size, geography, and a few other characteristics.

[19] One percent of respondents report they score strategic stretch on all six dilemmas. In other words, they have scored themselves five points on all questions on strategy, operations, and culture. I do not think these are reliable answers, and they should be ignored.