"Fix the roof during the summer," versus "We'll cross that bridge when we get there."

As a general rule of thumb in business, the higher the reward, the higher the risk.[25] Having the first-mover advantage in a market means setting the rules of the game, gaining dominant market share, and generating higher profits as long as the competition has not caught up. But all the risk is yours as well. You will be the first one to make all the mistakes, as there are no established best practices. Conversely, waiting until you have it all figured out means others will have taken the market already. All that is left is a me-too strategy, without any brand premium or competitive differentiation. Margins are small and may even be negative if the resources left over in the market turn out to be limited. All the talented people work somewhere else, suppliers are shipping to others that did place their bets in time, and investors bring their capital elsewhere, as you appear not to be in touch with the market. If there is no risk, there is likely no reward. Over time certainty increases, but the expected performance decreases.

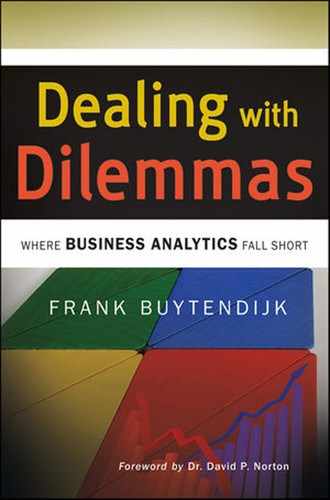

Figure 6.1 shows there is a trade-off between the moment to make the right decision and place your bets, and the value of that decision. If you analyze too long, the window of opportunity closes; you have suffered from analysis paralysis. If you jump on a new opportunity immediately–"shoot first, ask questions later"—your fail rate is most likely to be higher than others as well. But there is an optimum between risk and reward. Increasing your chance of success by thinking things through is worth the loss of a small amount of reward.[26]

How can you know you are reaching an optimum? The window of opportunity is not always known. And you also do not know which vital new insights will come tomorrow. Further, while getting to the bottom of things with your analysis, chances are that instead of more clarity all you get is more ambiguity and confusion. But the point of getting more insight is not about more clarity. It is about gaining a better understanding of the problem's complexity. At the bottom of most problems a fundamental dilemma can be found. As counterintuitive as it sounds, in the case of now-and-later dilemmas this means that increasing confusion, ambiguity, and disagreement actually is a sign of progress toward the optimum decision point.

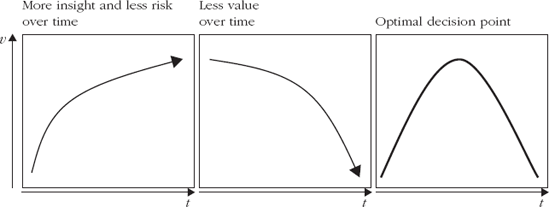

Figure 6.2 shows the dynamics of the decision-making process with a little more detail, using the idea of the S-curve.[125] S-curves describe the rise and fall of trends, the lifecycle of products, services, organizations, and markets.[27] A trend starts hopefully; with a lot of passion, a small group of people pioneer a technology, test a new business model, or bring a new product to market. This is usually followed by a phase of disappointment. The new development turns out to be something less than a miracle. Reality kicks in. At some point, best practices emerge and a phase of evolution follows. Product functionality improves, market adoption grows, and the profitability increases. Then something else is introduced, usually by someone else. This can come from a competitor, but also from an entirely new market. Think of mobile phones replacing navigation systems, computer games challenging the market for children's books, or ready-made meals in the supermarket encroaching on fast-food restaurants and pizza delivery. This replacement then goes through the same steps.

The best place to jump to the next S-curve to secure sustained growth is obviously at the beginning of the "eye of ambiguity." While the current cash-cow business is still profitable and growing, the next wave can be adopted, preparing for future profitability. Both the now and the later are considered in an ambidextrous way. The cash-cow business can fund the new investment. The new trend has not broken through yet, so there is time to experiment in a safe way. Experimentation leads to additional insight on how to capitalize on this new trend, which decreases the risk of failure and moves you toward the optimal decision point.

Yet, paradoxically, the least likely point to jump to the next S-curve is at that exact same point.[28] The growth of the cash-cow business is uncontested. The new trend is certainly still underdelivering in terms of functionality or in any other type of added value. The profitability is low, and the investments will not meet the established hurdle rate that the organization requires for its current growth trajectory. And who says this new trend is going to be a success? Furthermore, the eye of ambiguity is a source of great confusion. Experts disagree on the impact of the new trend and the benefits are more of a promise than a proven reality. And in difficult times we tend to rely on what we know and what has proven to work best. As a result, most likely nothing will happen until the new trend has overtaken the old one, and it is too late.

A classic example of this is Polaroid and Kodak,[126] which missed the boat with digital photography. Another example would be the U.S. car manufacturers[127] that have missed the trend toward more economical cars and have kept building SUVs. Think of Motorola failing to see how the cellular handset business was shifting from analog to digital technology.[128] Levi's[129] did not merely misread the shift away from department stores, it also missed trend after trend, making jeans in out-of-favor colors or coming late to new looks like baggy hip-hop jeans. Plotting your particular position on the S-curves is a good start to opening your eyes for the change to come.

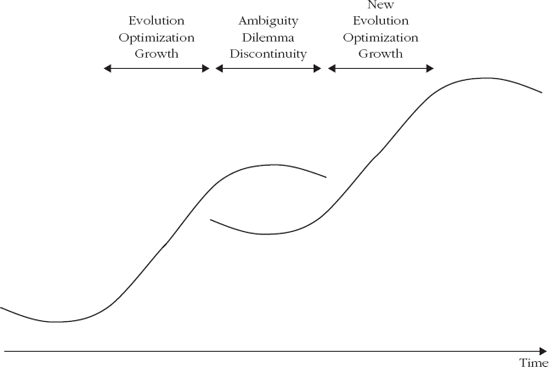

But as Figure 6.3 shows, how do you know that this new trend you have spotted really is the next S-curve, and not just hype that will blow over before things return to normal? And how can you know whether the curve you are on will collapse (discontinuity) or keep on growing (continuity)? When do you take a wait-and-see approach, and when should you place your bets as soon as possible?

If you decide too soon, you could bet on the wrong trend unnecessarily. If you decide too late, it can be a missed opportunity altogether. In short, you delay decisions when the risk and cost of missing the mark is bigger than the risk and cost of a missed opportunity. You expedite decisions vice versa when the risk and cost of a missed opportunity are bigger than the risk and cost of missing the mark.[130]

Defining the optimal decision point is a meta-dilemma: a dilemma on how to deal with your dilemma. The meta-dilemma is solved by having the tools to create the optimal decision point yourself. Sometimes it is imperative to take action immediately, particularly in situations that may deteriorate rapidly and exponentially. Think of product recalls that have an immediate impact on the organization's reputation. Or think of any situation in which you run the risk that someone else will make the decision for you, usually not having your best interest in mind. For instance, in some industries, the major players have been given a chance to come to self-regulation before regulation is imposed on them. An example would be sustainability reporting, something most large organizations already do, although in many countries it is not a legal obligation. Or think of a code of conduct around direct-marketing activities. Another situation where it is necessary to respond immediately is in operational issues that impact the whole organization, such as a cash-flow problem. Running out of money can easily mean bankruptcy in a matter of days or weeks. Finally, all unforeseeable events might call for immediate action, such as 9/11. Reportedly, Southwest Airlines had its complete business re-planned in just four days, while other airlines were still planning the board meeting to discuss the issue.

At other times waiting is good. Let others make the first mistakes, create all the awareness, and then you hit the market with a next-generation product or technology. There is certainly an art to finding the optimal decision point. It requires reevaluation of the matter on a very regular basis, like weekly, daily, or even continuously. The law of diminishing returns is important here. When you notice that the impact of new discoveries and insights decreases when reevaluating the matter, you are nearing the optimal decision point.

At first glance, this seems to contradict the previous statement that the best moment to jump to a new curve is at the beginning of the eye of ambiguity. The more you reevaluate, the more confusion you will find, instead of more clarity. But the jump does not start with making a strategic decision, making a big choice. The jump starts by opening your eyes for it. And the increasing ambiguity can be exactly those insights that you are looking for. Remember, at the bottom of difficult problems there is a dilemma to be found. Once in the middle of the eye of ambiguity, the trick is to buy some time to increase your chances of success. You can impact the optimal decision point; it is not a given.

You need not have a strategy that aims to reap the first-mover advantage. A fast-follower strategy limits the risks while keeping chances of success relatively high, capitalizing on the opportunity. TomTom was not the first to offer navigation systems, but it managed to get it right. The Apple iPod was not the first mp3 player, but it has a dominant market share. The Apple Newton was the first PDA with handwriting recognition, but it never made it to the main stage. A variation on this theme is growth based on acquisition, something large enterprises can afford to do. Wait until a niche player becomes the successful market leader in that segment, and then—as part of a portfolio strategy—simply acquire the company. This is often the deliberate strategy of niche companies that are backed by venture capital: to be acquired by one of the 600-pound gorillas in the market. Other ways to dip a toe in the water would be through a partnership, a joint venture, sponsored academic research, and so forth.

These are all examples of strategy as a portfolio of options. These are decisions that can be reversed when needed without too much damage. These decisions require a certain level of commitment, but not for the long term. And the different types of associated organization forms make it possible to stage the commitment—from a partnership to a joint venture to an acquisition. You have effectively bridged the now and the later.

There are many eyes of ambiguity in today's business. Take, for instance, the whole "green" movement, or, in broader terms, the corporate social responsibility (CSR) wave. For every study that says there is a relationship between a company's CSR rating and its financial performance, there is another study showing there is no such relationship. And other studies show inconclusive results. Fortune magazine writes in 2007 that except for a few cases, such as General Electric's Ecomagination portfolio, there is no demonstrated link.[131] The Journal for Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management states also in 2007 that the FTSE4GOOD index—the Financial Times sustainability index—does outperform the relevant benchmarks, but only due to risk differences.[132] Another study [133] shows there is no difference in risk-adjusted returns. In 2008, The Economist [134] quotes an exhaustive academic review of 167 studies over the past 35 years that concludes that there is in fact a positive link between companies' social and financial performance, but only a weak one. Firms are not richly rewarded for CSR, it seems, but neither does it typically destroy shareholder value. Maybe the relationship becomes stronger with time, as we have not yet figured out how to execute on CSR principles. Maybe today's effects will be visible in the longer term, and we are not yet past the incubation stage. Time will tell.

At the same time, $1 out of every $9 invested is already related to some kind of CSR-weighted fund.[135] Many pension funds weigh the management ethics and social responsibilities of corporations before making their investments. As the former chief investment officer of ABP, one of the largest pension funds in the world, says: "There is a growing body of evidence that companies which manage environmental, social, and governance risks most effectively tend to deliver better risk-adjusted financial performance than their industry peers. Moreover, all three of these sets of issues are likely to have an even greater impact on companies' competitiveness and financial performance in future."[136] Also, various CSR-driven financial indexes have emerged, such as the Dow Jones Sustainability Index, Ethibel, SERM, and FTSE4GOOD.

What should one do? There is no uncontested evidence that CSR is the right way to go, yet we cannot afford to miss such an opportunity. CSR practices are not only meant to improve the bottom line, but can also be seen as positive PR, solid risk management, or a cost saver on upcoming carbon taxes, so, it makes sense to put in some CSR options in the strategic portfolio. They have short-term merit, and benefits may materialize further over time. You can increase your stakes over time as well. Start with carbon reporting before moving to carbon planning. And look at the green aspects of a newly introduced product before applying green principles to the cash-cow business.

Another good example of the eye of ambiguity is dealing with a recession. July 2007 marked the beginning of the credit crunch. There had been many recessions before; the last one began in 2001. This present recession at first seemed to be restricted to financial services and seemed to be mainly a problem in the United States, yet—given the interconnectedness of banks worldwide and the size of the subprime mortgage problem—it was significant. The problem deteriorated, as banks lost trust in each other and were unwilling to supply short-term loans. As banks depend on the circulation of money, this soon became an issue for large banks around the world, and they needed infusions of new capital. Consumers lost trust as well and stopped spending. In many countries the real estate market ground to a halt. Banks were unwilling to provide mortgages to protect their balance sheet, while consumers were unwilling to buy a new house because of uncertain times.

From there also the real economy spiraled down, impacting the automotive industry (which turned out to be not too healthy to start with), trade and transport, travel, and so forth. Once the first signs of economic trouble appear, what should you do? One cannot be certain what is going to happen. Reacting immediately could lead to not hitting the mark. But the risk of not responding at all greatly outweighs the costs and the risk of missing the mark. Where buying time to get it right is the way to go for CSR, dealing with a recession requires immediate action. In a 2008 study, consulting firm Accenture examined why some companies manage downturns more effectively than others.[137] Their answer: The best performers watch for downturns and take action quickly. By contrast, executives in more poorly performing companies may accept that their industry is slowing down but hold their breath in the hope that things will get better before any difficult actions are necessary. Another conclusion of the study was that a strong cash position allows the winners to be flexible. This is a very good example of combining the now and the later. Cut costs quickly and decisively at the first sign of trouble, to free up cash. In fact, this is a strategy that creates options. The cash can be used in multiple ways that cannot yet be foreseen. Reacting quickly makes it possible to get through the eye of ambiguity.

One industry that seems to be in a continuous state of ambiguity is the IT industry. Paradigms succeed each other with amazing speed. Mainframe architectures were succeeded by client/server structures, leveraging the power of the then-upcoming personal computers. That paradigm lasted less than ten years before it was succeeded by Internet computing. Internet-based architectures now enable the next step: service-oriented architectures. The software paradigm has radically changed, too, with everything being 2.0, focusing on user-generated content, multimedia, interaction, personalization, and collaboration. IT organizations have greatly changed. Sourcing is the keyword, with derived terms such as outsourcing, partner-sourcing, off-shoring, near-shoring, right-shoring, and right-sourcing. And did I mention cloud computing?

Are you confused by all these buzzwords? That is exactly the point—it indicates the presence of the eye of ambiguity. The dilemma between now and later is very apparent. Having the first-mover advantage could easily lead to being on the bleeding edge where excessive initial investments may lead to underwhelming or at best unclear returns. Yet, being the first one to adopt could also lead to competitive advantage. You set the rules for the rest of the market and build deep experience. Given that technology skills can take a long time to build and that some of the skills are rare, this would be a valuable asset.

What should one do? Technology development seems to have a life of its own. It is usually not very demand driven and the actual business need can sometimes be an afterthought. And technology innovation "for the heck of it" does not seem like a good strategy. Unfortunately, there is no single answer. The best response here is situational. Some decisions are best delayed, while others need to be made upfront. An IT systems landscape can be divided in two parts: a technology infrastructure or architecture, and a set of applications. The speed of implementing applications, or modules of them, should be high. But the speed of change in the architecture tends to be very slow. If done well, radical choices are made perhaps every ten years or so. The decision for the right platform and the right architecture is crucial. Given the slower pace of development, there is time to find the optimal choice, but the decision should not be delayed. The key criterion in making the decision on how to structure your IT architecture is about what options the decision creates. The more open and flexible the architecture is, the more options it creates.[30] If there are many options, you can delay the choice for the right application until the moment you need it. A well-defined architecture greatly speeds up the implementation time of an application, as all the basics are already arranged. Moving slowly and quickly at the same time is the hallmark of a strategically thinking CIO.

The now-and-later examples all dealt with externally inflicted dilemmas: corporate social responsibility as a trend, the economic situation, and technology development. But jumping to the next curve does not have to be a reaction—you can also drive the change yourself. In fact, this would be a preferred strategy for creating competitive advantage. The competition is facing the eye of ambiguity—whether you will be successful or not—while you have the advantage of following your plan and knowing your intentions. Creating a portfolio of options is a more active task than waiting to see which options actually pan out. This would lead to uncoordinated diversification—a financial portfolio of activities mostly based on maximizing return on investment. In a more active approach, the portfolio of options is used to create new and unique combinations that lead to innovation and competitive advantage.

For example, in the early 1970s, starting in France, bancassurance became popular.[138] Bancassurance means an integrated product, marketing, and sales approach to both banking services and insurances. This leads to cross-sell opportunities, products that combine elements from both businesses—such as life insurance as part of your home mortgage—and it is also good for customers if it leads to better prices. These combinations started out as partnerships and the creation of internal subsidiaries, but in the 1980s and 1990s, bancassurance triggered large acquisitions, creating huge financial services institutions. The bancassurance concept also spreads the risks. In economic good times people may be more interested in investment projects, whereas in uncertain times people focus more on being well insured. Although both types of business are about financial services, the business model, the value drivers, and the customer relationship strategies are very different. For instance, insurance companies do not interact with their customers very often, while banks try to have a continuous line of communication with their customers. In light of the recession of 2008/2009, the pendulum swings again. Bancassurance combinations have become "too big to fail," and are now seen as a liability to society. Some financial institutions behave proactively, and again split up.

Unfortunately, sometimes unique combinations do not work out the way they are envisioned. In 2002, online marketplace (auction web site) eBay[139] acquired online banking system PayPal for $1.5 billion, followed by the acquisition of Internet phone company Skype in 2005 for $2.6 billion. The idea was not only to combine the flow of goods (the online market) with the flow of money (the payments), but also to include a flow of communication (Skype). The combination did not materialize at all; no synergies emerged. In 2009, Skype was sold again to Silverlake (an investment firm), at a considerable loss. In the end there is always strategic uncertainty.

[25] Risk and reward are obviously related. The higher the reward, most likely the higher the risk involved. However, it does not work vice versa. Taking high risks does not lead to a greater chance of a high reward. In many cases, on the contrary: The higher the risk, the lower the chance of success.

[26] For instance, a 90% chance on $ 90 revenue averages a return of $ 81. This is better than an 80% chance on $ 100 revenue, which averages $ 80.

[27] Explanation of S-curves is loosely based on C. Handy, The Age of Paradox, Harvard Business School Press, 1994. The phrase "eye of ambiguity "is my own choice of words.

[28] Although Christensen does not use the S-curve metaphor, this explanation is based on C. Christensen, The Innovators Dilemma, Harvard Business School Press, 1997.

[29] This is a very good example of a dimension shift, from time to space. Space here is represented by the partner environment.

[30] As in so many cases, this is a dilemma in itself. Systems that are flexible may at the same time be more complex, or score lower on performance and efficiency. This is the price of having many options.