In the Batman movie, The Dark Knight, District Attorney Harvey Dent flips a coin three times. "Heads it's me, tails it's you," he tells Rachel Dawes, deciding who will be lead counsel at a trial. The coin comes up heads. "Would you really leave something like that up to luck?," she asks him. "I make my own luck," he replies.

You could be lucky, and the dilemma you are facing is simply a complex optimization problem.[31] Most managers are not mathematical experts, and there is no need to be one. However, it is important to know when someone with those specific skills is needed to do some serious number crunching. The good news is that there is a substantial body of techniques that can help find an optimum choice between various alternatives. Complex organizations generate complex decision problems. A rigorous, even scientific, method of investigating and analyzing these problems is necessary. During World War II, requiring better decision making in both economic as well as military issues, the discipline of operations research (also known as management science or quantitative decision making) was born.[140] Operations research (OR) includes techniques such as simulation, decision trees, linear programming (maximizing results while working with limited resources), and dynamic programming (e.g., to find the shortest route for deliveries). Unfortunately, operations research is not widely used. The Dealing with Dilemmas survey showed that 60% of respondents have never heard of it, or are not using it. OR is a standard in only 5% of companies.

It may not be necessary to master all these techniques, but it is important to recognize that a certain complex problem could in fact be tackled with one of these techniques. Here we concentrate on recognizing how to optimize between various alternatives that could be seen as a dilemma if we were not aware of these techniques.

Some cases represent what I call a many-of-these versus many-of-those problem. Should we buy lots of handguns (cheaper, so we can afford more) or rifles (offering more firepower) to maximize the effectiveness of our platoon? What mix of vegetables of 200 grams per person provides the most vitamins and variety within a single portion of food? What is the best marketing mix to reach as many people as we can? Another type of problem involves merely a one big this versus one big that. It is either this strategy or that one, to save costs. Either focus on cost savings or on investing in growth. Either buy a motorbike or go on vacation.

Putting together a mix of marketing communications is a question of optimization. The goal is to maximize the number of responses, or leads. These can then be qualified as to how serious they are and passed on to the sales department, whose job it is to convert those leads into actual sales. Let us consider how to optimize the mix.[32] GloAsia (fictitious name) is a global trading firm that tries to reach customers worldwide. For a particular campaign the question is raised whether it should be done by traditional direct marketing (DM) or via Google ads. Logically, there can be three outcomes of the analysis. In its simplest form, one choice always turns out to be better than the other. Alternatively, both choices could be equal; it does not matter what you choose. Finally, there could be a true optimum, a mix of DM and Google ads that yields the best return.

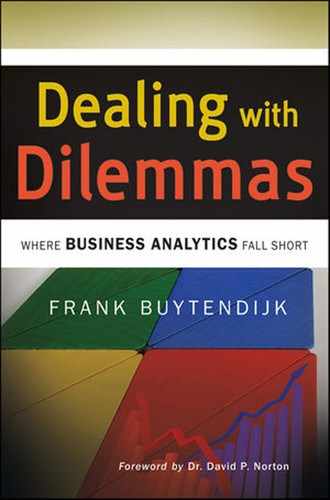

For instance, assume the budget is $1,000. One Google ad costs $40 and you get 10 responses. A direct-marketing letter may cost $1 and you get a response in only 10% of cases. If you stick all your money in Google ads you will get 250 responses from 25 ads. And if you spend the complete budget on direct marketing, you will get 100 responses from 1,000 letters. With this example, putting all your money in Google ads is the best choice and cannot be bettered with any other combination (see Figure 7.1).

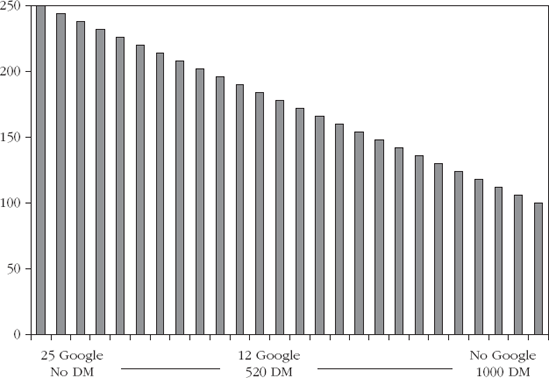

This is not always the case. Make a small tweak to the assumptions and we can generate an example with numerous "optimal solutions." Assume the budget is still $1,000. A Google ad now costs $50, and you will still get 10 responses. Assume a direct-marketing letter still costs $1, but, by using improved messaging and more targeted delivery, you now get a 20% response rate (i.e., 1 in 5 letters gets a response). If you focus completely on Google ads you will get 200 responses from 20 ads, and if you decide to use only direct marketing, you will get 200 responses from 1,000 letters. In this example, it is impossible to pick which is the best option, as in addition to these two equally good choices, there are a further 18 choices that will also give you the maximum return of 200 responses (i.e., 19 ads and 50 letters, or 18 ads and 100 letters, or 17 ads and 150 letters, and so on). Each uses up the entire budget and each combination gets you 200 responses (see Figure 7.2).

Again, there is no dilemma. Every choice is perfect. You could argue that this is a dilemma in itself: which one to pick if it does not matter. This can be a surprisingly difficult choice. The key to picking one is to identify other objectives in addition to creating a maximum return of responses. For instance, Google ads might be a new communication medium for you and you would like to test how it is working for you, although you and your customers are used to direct marketing. Allocating a small part of the budget to Google ads would be a logical result. Perhaps using two channels creates a bit more complexity in reporting the results; different systems have to be used to get to the right numbers. In that case, choosing one or the other makes more sense. Or, you are equally experienced in both ways of customer communications and you would like to compare them on an even basis. Spending half the budget on one and the other half on the other may make sense.

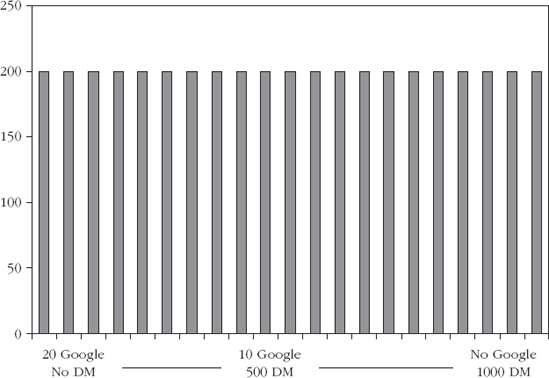

In most cases, reality is a bit more complex. Usually more constraints apply. Let us go back to the original problem and assume that the budget is $1,000 again, a Google ad costs $40, and you get 10 responses, whereas a direct-marketing letter costs $1 and you get a 10% response rate (i.e., 1 in 10 letters gets a response). Say that there is a budget for Google ads for all campaigns, and this budget allows you to purchase only a maximum of 16 ads in a given period. Also, assume there is a minimum print run for letters of 500.[33]

If you spend as much as you can on Google ads, your maximum response would be 160 from 16 ads (the limit), costing $640, but you cannot get any letters from your remaining $380, as the minimum print run is 500. If you spend your entire budget on letters, then you will get 100 responses from 1,000 letters. Can we do better than this? Yes: By spending $480 on 12 Google ads and $520 on 520 letters, you will get 172 responses. This is the optimal solution to this "constrained optimization" problem, which cannot be bettered. Again, there is no dilemma, but a single solution (see Figure 7.3).

Finding the optimal solution for this problem requires going through all combinations of Google ads and direct marketing, in other words, creating a linear program. Linear programming, as part of operations research, is a key technique for optimization.

There is more to business than mathematics. In fact, lifting constraints is the basis of most innovation. TRIZ, a Russian methodology for problem solving, is based on a classification of different constraints (or contradictions) that can be the cause of a certain problem.[141] For instance, everyone wants the battery life of their mobile phone to be better, but not many would be willing to accept a heavier or bigger mobile phone to hold a more powerful battery. Battery size and weight are at odds with battery life. The TRIZ classification identifies a total of 39 different constraints, including cost, weight, speed, strength, shape, temperature, complexity, stability, and so on. Although TRIZ was originally developed for engineering, it can also be used for business management. Business management is also constrained by factors such as cost, time, sustainable growth rate, available skills, and resources.

Once we understand the impact of the constraints, we can find ways to lift the constraints and get more responses. The GloAsia example showed three constraints: the budget, the amount of Google ads, and the minimum number of letters. One way of finding additional budget would be to team up with a partner and make it a joint campaign. Or you can combine campaigns within the company that each target the same audience. You could find alternative online or direct-marketing channels that are lower priced, say by 20%, but with a response rate that is less than 20% lower. Direct marketing was possible only as of 500 letters. Perhaps working with a different vendor or technology lowers that number. The maximum number of Google ads perhaps was based on a concern not to depend on one channel too much and to spread the budget over multiple channels, reaching more individual "eyeballs." Is this assumption true? Perhaps this logic can be challenged and turned around. It could very well be that the power of repetition creates leverage for future campaigns. In this way, every campaign creates a certain percentage additional response in the next campaign. This spillover effect can also be used within the mix of a campaign. Clicking on the Google ad may lead you to a web page where you can register for a direct-marketing newsletter, improving DM response. And the direct-marketing piece could refer to the web site that the Google ad refers to, to further increase web responses. Obviously, the mathematics of calculating the expected response become more complex, but the results improve.

In order to maximize the return on investment, organizations need to operate on the productivity frontier. In other words, resources such as capital and labor must be deployed in such a way that they deliver the highest productivity and returns. Get the most out of what you have. The optimization exercises that compared Google ads and direct marketing provided a good example. Modern portfolio theory further builds on the idea of optimizing results, specifically addressing risk versus reward.[34] Modern portfolio theory is based on the premise that investments (like stocks, or bonds, or real estate, or just about anything you can buy in the hope of making money) have three important properties:

The return generated by the investment

The risk of the investment (the uncertainty that we will get the return)

The correlation of investment returns

For example, we could look at investments like government bonds of a stable country and forecast that, based on performance of these bonds over the past 10 years, the returns are low (perhaps 3% per year), the risk is also low (over the 100-year history, the government has never defaulted on its bonds), and its tendency to behave like other investments is relatively low. Other investors, perhaps with a higher risk appetite, would consider investing in a venture capital firm that supports startup companies in biochemistry. The return could be considerable (perhaps 1,000% over time), but the risk is extremely high (80% of all investments may not provide a return at all).

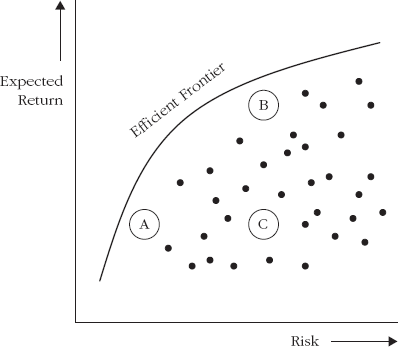

Harry Markowitz (who later won Nobel recognition for his work on modern portfolio theory) looked at a collection of possible investments by generating a chart with risk increasing to the right on the horizontal axis, and return increasing upward on the vertical axis. In its simplest version in Figure 7.4, the small dots are possible investments, and three of those possible investments (A, B, and C) are highlighted.

In Figure 7.4, first note that as the risk of investments increases, it is possible to get greater returns. This illustrates the rule, "no risk, no return." Now, look at three possible investments, A, B, and C, each representing stocks in a well-known company. Given a choice between A or C, which would make the best investment? The correct answer would be A, because it provides the same return at a much lower level of risk. An investor would be foolish to invest in C, taking unnecessary risk. Now consider between investing in B and C. B would be the superior investment, because you are receiving a much higher expected return, within the same risk profile.

So Markowitz concluded that investments up toward the efficient frontier curve would generate the highest return for whatever level of risk the investor could tolerate. So both A and B would represent more "efficient" investments, with both providing maximum returns at their respective risk levels. A conservative investor would prefer A and take smaller returns in exchange for lower risk, whereas a more aggressive investor would prefer B—being willing to take more risk for higher returns.

That leaves the third property of investments, the tendency of an investment's returns to behave in a similar way to the returns of other available investments. In other words, investments correlate. Correlation is very important, because when investors buy multiple investments (a portfolio) that include stocks whose returns are weakly correlated (i.e., their returns do not behave in exactly the same way), then something very beneficial happens: Their portfolio becomes diversified. This means that if one of the investments held in a portfolio suffers a loss, perhaps other investments will dampen the loss the investor would have suffered if she had held only the one investment. Diversification of a portfolio makes it possible to achieve higher returns for a given level of risk than most individual investments that are available.[35]

The idea of portfolio management can also be applied in a broader sense, to deal with one-big-this versus one-big-that dilemmas. Classical strategic thinking stresses the important of making big choices: either cost leadership or differentiation. Or in a more subtle version: You need to be sufficiently successful in all value disciplines, such as operational excellence, customer intimacy, and product innovation, but excel in one of them. It is strategic thinking like this that creates strategic dilemmas, either one strategy or the other. However, there is also a good body of evidence that pure strategies are not necessarily the best ones. A combination of differentiation and cost leadership could also lead to superior business performance.[142]

There is a way to break the one-big-this-versus-one-big-that strategic dilemma, and create an effective hybrid strategy. First, we decompose the strategies into smaller elements, the strategic goals into smaller goals, the choices on the table into smaller choices. Then we start to recompose those goals into a single picture, or into a new strategy, thus avoiding an either/or choice.

Particularly in a downturn economy, cost cutting is important. How to cut costs poses a common dilemma. It is easiest to cut a complete business activity, such as a product, geography, or a business unit. The disadvantage is that you will be cutting revenue streams as well. The alternative is shaving costs across the board, where each unit will have to cut, for instance, 5 or 10%. However, this means that every business function suffers and handicaps its execution. Essentially, it is a sucker's choice again. Who says these are the only two options, and you have to choose? Perhaps it can be a combination of the two: selling off a small activity representing just a part of the needed cost savings, so that other units need to cut less. Perhaps cost cutting is not even necessary, but scrutinizing working capital management would be enough

In case these are indeed the two choices, how can you cut costs without harming revenue streams, and without harming execution of the total business? This can be done if we can identify the costs that do not influence revenues, directly or indirectly. These costs can be identified if we understand what the "value drivers" in the company processes are, for instance, through an activity-based management initiative. Value drivers could be the reliability of a production process, or the reputation of the company, or, indirectly, a certain information system, the speed of externally reporting business results, or the rigor of working capital management. Once we understand those value drivers, all costs not associated with this can be cut without greatly impacting the health of the company.

The actual problem here is hidden under the surface: thinking about efficiency when it is too late. Not making the right decisions early on has led to your range of options all having negative side effects. The dilemma is self-inflicted. In fact, it would be better to display anti-cyclical behavior and make sure to create an optimal cost structure during better times. Getting to a deep level of insight into value drivers and restructuring accordingly takes time.

Consider Direct Bank,[36] which offers simple loans and savings accounts via only two customer contact channels, the Web and the call center. Direct Bank has operations in multiple countries. The Web infrastructure is centralized, and there is a call center in every country, as consumer confidence is partly based on physical local presence. As part of its growing ambitions, corporate increases its targets for the return on capital employed (ROCE). The management team brainstorms and comes up with a few options. Trying to increase the operational excellence by centralizing call centers in multiple countries will certainly cut costs and increase margins. Another option is to reinvest the assets under management in a more aggressive way. The marketing director offers to start a large campaign to increase market awareness. Finally, a junior manager brings in the idea to create a product for "Islamic banking," unlocking the large ethnic communities in various countries where the bank is active. The management team summarizes the options as shown in Table 7.1.

Table 7.1. Direct Bank Options to Improve Return

Advantage | Disadvantage | |

|---|---|---|

Close call centers | Easy cost saving calculation | Negative impact on consumer trust |

Change reinvestment policy | Higher return, no change operations needed | Higher risk in |

Market awareness | Top-line improvement | Process for handling large numbers of new customers not scalable enough |

Islamic banking | Blue ocean growth | No direct return |

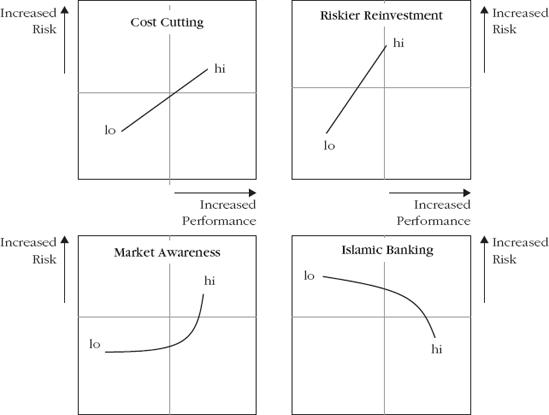

This is a true dilemma: Each choice has unacceptable disadvantages. But why look for just one alternative to reach the new objective, when a portfolio of improvement activities might do the trick? (See Figure 7.5.)

Each option is represented with a line, from "low" to "high." Low here means only moderate changes are made; high means drastic redesigns are carried out. The line provides a visual explanation of how much impact the performance can have. The line can be horizontal, which means the performance improvement activity can be scaled up without additional risk. The line can go up, as it will do in many cases, to show how the risk will increase proportionally or disproportionately when the performance improvement initiative is implemented more aggressively. And there are cases where the risk actually goes down at the same time as the initiative has more impact. This last case is preferable because the initiative reconciles the natural dilemma between risk and performance.

None of the options provides a perfect answer, as long as they are viewed separately. However, the picture changes once you consider multiple options, each contributing at an acceptable risk level. Instead of the point solution to performance improvement in the traditional way of thinking, a performance improvement portfolio emerges.

Changing the risk profile of the reinvestments should be dismissed by the management. It would increase the risk significantly while the returns would be marginal. Cost cutting in call centers is still possible, not by closing call centers but by investing in an infrastructure that integrates call centers so that local employees who speak multiple languages can also help customers in another country. By itself, that might not save enough costs, so it helps to also increase market awareness, yet not so aggressively that the current processes and systems cannot cope with the follow-up. The joint performance improvement more than makes the goal. The idea of Islamic banking remains. With the strongly improved contribution, a part of the returns can be invested in setting up an Islamic banking pilot in a single country and serving a single ethnic group. It allows the bank to follow-up on the results and build up the necessary competency. The bank is investing in its next round of performance improvement.

There are always cases where the choices you are confronted with include no elegant way out by creating a portfolio of small solutions that together tackle the one big, hairy problem. Those are dilemmas in the classical sense: You have to make a binary choice. And no matter what you choose, values you hold dear will be compromised. People are going to get hurt. In our personal lives, we may have experienced this going through a divorce, and sometimes in the newspaper we read how parents turn in their criminal children to the police. We can also recognize this in business.

For instance, you have to lay off a significant part of the workforce in order to make sure the shareholder value does not totally collapse, or even to prevent the company from folding. Or you need to sell off a strategic business unit in order to refund a new strategic initiative project that has massively gone over budget.

These are cases where all options have significant disadvantages. You can also be confronted with the sort of dilemma that forces you to choose between multiple priorities, while there really is no chance to mobilize the resources for all priorities. As the minister of social affairs, you need to invest in a project either for homeless people or for disadvantaged children while the budget allows only the minimal possible investment. And what if there are only enough skills and resources available to comply with just a part of the new regulations, and the clock is ticking? If you were the CEO, what would you choose?

Perhaps there is no way out, and there is no choice but to live with the consequences of whatever decision you make. Preventing it from happening was the only thing you could have done, by having made the right choices and decisions beforehand. But that is history; now it is too late. Hopefully, as a professional, you learn from this, and you find a way to prevent something like this from happening again.

Still, the question remains as to how you will communicate those choices, and which moral appeals you have to make. This is also an integral part of dealing with you-and-me dilemmas.

[31] You could also argue the opposite, that finding out you are dealing with a false dilemma should be disappointing, as dealing with a true dilemma represents a chance to come to synthesis, and fundamentally solve a problem.

[32] I would like to express my thanks to Dr. Ziggy MacDonald for helping with these examples. I am "quantitatively challenged, "but Dr. MacDonald has the gift of bringing complex matters back to an understandable set of steps that even I understand.

[33] Mathematically, if you let R be the total number of responses, G be the number of Google ads, and DM be the number of letters, then the problem is written as:

Max R = 10G + 0.1DM

Subject to 40G + 1DM ≤ 1000

G ≤ 160

DM ≥ 500

G, DM ≥ 0 and integer

[34] I would like to thank Steve Hoye and Jim Franklin for contributing their description of modern portfolio theory.

[35] This is another example of a dimension shift between space and time. You can wait for a stock to perform well over a period of several years, smoothing the ups and downs over time, or you can look for a portfolio of stocks (the space dimension here), smoothing ups and downs immediately.

[36] Example is based on F.A. Buytendijk, Performance Leadership, McGraw-Hill, 2008.