Like all organisms, the living company exists primarily for its own survival and improvement: to fulfill its potential and to become as great as it can be.

The goal of every organization is to sustain itself. And management gurus all over the world have been looking for the elixir. Jim Collins introduced the BHAGs (Big Hairy Audacious Goals) and Level 5 leadership.[172] Peters and Waterman introduced eight attributes, among which are a bias for action, being close to the customer, and sticking to one's knitting.[173] Another study[174] adds quality of management and employees, as well as a long-term orientation and a focus on continuous improvement. One of my own studies,[175] in 2005, showed that many disciplines were searching for the high-performance organization, each from its own angle. Management gurus would focus on leadership, customer relationship management evangelists would focus on the customer, and HR specialists would emphasize teamwork.

I have come to the conclusion that the key to sustainable success is the ability to deal with dilemmas. Thinking about it, it is only logical. The two corner pillars for dealing with dilemmas that I described in the book are creating synthesis and creating options. Synthesis is the tool of innovation. Most innovation comes from solving a contradiction.[176] Making something light enough to be powerful and portable; making something safe and fast; making something functional and easy to use—these are all examples of synthesis. Innovation is a prerequisite (although not a guarantee) for a sustainable business. Creating options makes it possible for a company to adjust when reality changes. It creates organizational agility. And according to Darwin, the ones that adapt are the ones to survive.

Furthermore, the notion that dealing with dilemmas is key to sustainable success is supported by the most important themes of what is considered sustainability today: environmental concern and corporate social responsibility. The Brundtland Commission, also known as the World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED), defines sustainability this way: "Sustainable development is development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs."[177]

The most common definitions of corporate social responsibility (CSR) come from the International Standards Organization (ISO) and from the European Union (EU). ISO defines CSR as "a balanced approach for organizations to address economic, social, and environmental issues in a way that aims to benefit people, community and society."[178] The European Union defines CSR as "a concept whereby firms integrate social and environmental concerns in business operations and in the interaction with their stakeholders on a voluntary basis."[179]

The ISO definition highlights the triumvirate of economic, social, and environmental issues, but focuses on benefiting not the organization itself, but people, community, and society. The EU explicitly mentions business operations, but fails to mention that CSR needs to be beneficial. My own definition of CSR is a combination of these two definitions:

Corporate social responsibility is a balanced approach for organizations to integrate social and environmental concerns in business operations in a way that aims to benefit the organization and its internal and external stakeholders.

Although CSR is only one side of sustainability, and sustainability—as we will see—is much more than environmental protection, these definitions reveal something interesting. Meeting today's needs while protecting the needs of tomorrow is almost a literal translation of the now-or-later dilemma. And the definition of CSR highlights that it must benefit the organization as well as its stakeholders. That is a classic you-or-me dilemma.

Sustainability, therefore, is being able to deal with you and me, as well as now and later. As the goal of an organization is to sustain itself, the management needs to successfully deal with dilemmas.

The current focus of organizations on social and environmental issues as their interpretation of sustainability has its pluses and minuses. On the positive side, it shows that focusing on shareholder value only while ignoring other stakeholders leads to problems, and that a different approach is needed. On the flipside, as always in situations that are in the middle of the eye of ambiguity, opinions on what to think about it and how to tackle it vary widely,[59] clouding the bigger picture. Nobel Prize–winning economist Milton Friedman is quite clear in his opinion that the social responsibility of corporations is to maximize profits.[180] It is up to the shareholders to decide what to do with those returns. Then there are the proponents of corporate social responsibility as a goal in itself. In their view, organizations have a moral obligation to society. Environmentalists take this approach even further. Corporations need to invest in saving planet Earth, regardless of cost or loss of profit.

There are, it seems, two opposing schools of thought: those who feel CSR should not be part of a management agenda, and those who feel CSR is by default part of management's concern. However, those two sides can be synthesized. Peter Drucker starts out by stating that an organization is not entitled to put itself in the place of government or to use its economic power to impose its values on the community. But he also introduces an exception, which is when contributing to easing a social problem creates an opportunity for performance and results.[181] But Michael Porter takes the synthesis a lot further. Porter sharply analyzes the shortcomings of these opposite schools of thought because they focus on the tension between business and society rather than on their interdependence. Running a business does not preclude being a good citizen. In fact, these two objectives should be aligned. Being a leader in CSR, in Porter's view, is an opportunity to differentiate from the competition.[182] In our terms, CSR, which is about you and me, leads to a better competitive position, and a more favorable now and then.

However, given the current ways in which organizations, their hierarchy, and their strategic focus are structured, the odds are against an enlightened view. In the usual contrarian words of Henry Mintzberg, as early as 1983:

The economic goals plugged in at the top filter down through a rationally designed hierarchy of ends and means...[the] workers are impelled to put aside their personal goals and to do as they are told in return for remuneration. The system is overlaid with a hierarchy of authority supported by an extensive network of formal controls.... Now, what happens when the concept of social responsibility is introduced into all this?... Not much. The system is too tight.[183]

As I argued in Chapter 8, traditional management structures create strategic dilemmas.

So far, I have discussed dilemmas within the organization (intraorganizational). But based on the definition of sustainability, we need to expand our focus. We also need to manage stakeholders (of which social responsibility is one angle) and their conflicting requirements, in other words interorganizational dilemmas.

Most studies define the high-performance organization as an organization that outperformed its industry peers for a number of years. This is very much in line with traditional organizational theory, with its focus on shareholder value. In the classical sense, an organization is defined as a group of people sharing the same goal. Here we look at sustainability from an ecosystem point of view. Organisms have a reciprocal relationship with their environment (they give and they receive) and this relationship is circular in nature (the more you receive, the more you can give, which leads to receiving more). This view requires a focus on stakeholder value.[184] From a stakeholder value perspective, an organization is defined as a unique collaboration of stakeholders who realize that they can reach their own goals only by working together. Stakeholder theory defines the role of management as balancing the fiduciary responsibility of looking after shareholders' interests with the competing interests of other stakeholders for the long-term survival of the corporation.[185]

Redefining the concept of the organization has become a necessity. Globalization and technology have had an extreme impact on the transaction costs organizations have in interacting with others. Today, in many cases it is much better, cheaper, and faster to outsource activities, compared to the quality, cost, and speed of internally coordinating those activities. Outsourcing comprises support functions such as facilitary services, finance, and IT, but also logistics, manufacturing, and increasingly even R&D. In fact, over the past 20 years, there are indications that the average size of organizations has been shrinking.[186] Business is not a hierarchy anymore, based on command and control, with a CEO at the top of the food chain deciding which direction to take. Business should be seen as a network of organizations that communicate, negotiate, and collaborate when discussing strategic direction. Organizations are part of an overall "performance network." A performance network recognizes all stakeholders in a value chain, and aligns their objectives in order to optimize the performance of the overall network, instead of the performance of each individual stakeholder.[187]

The majority of business decisions impacting your bottom line are actually made outside the walls of the organization itself, in the wider performance network. You need to take stakeholders into account as part of strategy management. This starts with asking the question, "What do my stakeholders contribute to my success?" This question leads to a much higher leverage; as we aim to reach our strategic goals, we are not alone anymore. This question can be asked only if the opposite question is asked as well: "And what do I contribute to the success of my stakeholders?" These questions are the key to the performance network.

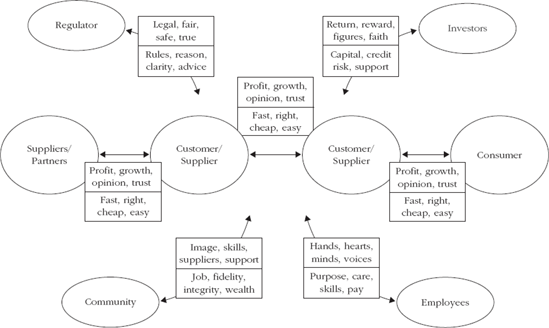

A huge contribution in how to manage the performance network comes from a methodology called the Performance Prism.[188] One of the key messages of the Performance Prism is that stakeholders have requirements, and they offer contributions. The methodology describes in great detail, among other things, what stakeholders could (and perhaps should) expect from each other. With this in mind, it triggers the right strategic and planned discussion. The requirements of different stakeholders or the requirements between a single stakeholder and the organization may not align, may provide tension, and may even be conflicting. Without realizing this, we may act on wrong assumptions, or worse, be ignorant of these needs. By understanding these objectives, we can find a solution to reconcile these differences; this probably will lead to much smarter solutions than optimizing a single set of objectives. Figure 10.1 and Table 10.1 provide an overview of an organization's stakeholders and their needs, according to the Performance Prism.

Figure 10.1 clearly shows how customer/supplier relationships are the basis of all value creation in the performance network. The suppliers of the organization view the organization as a client, while the organization again has its own clients. Organizations are looking for profit, growth, opinion, and trust downstream the value chain, and for fast, cheap, and easy products and services upstream the value chain. Other stakeholders, such as employees, the community, regulators, and investors, supply the means to propel value creation, making it possible. Regulators ensure fair competition, the community provides a platform to work in, such as infrastructure, investors supply the necessary capital to operate, and employees provide the needed labor. With this view in mind, none of the stakeholders can be ignored as each represents a vital component in making the value chain flow smoothly.

Each stakeholder has different requirements, and sometimes they can be conflicting. Employees are looking to be treated with care, and view the organization as their main source of income. The organization is in need of dynamic capabilities and may be looking for ways to quickly shrink and expand the organization, based on the state of the economy. As described before, between customers and the organization there is the value-versus-profit dilemma, and the same is the case between suppliers and your organization (as you are the customer). Many sales-driven organizations wrestle with the trade-off between the direct and indirect channel, figuring how much to do themselves and how much to leave to partners. Further, in regulated industries, the regulators and the competitors in the market can live at odds with each other. Businesses are trying to compete and are looking to surprise their competitors, whereas the regulators value predictability the most.

Figure 10.1. Graphical Representation of Stakeholder Requirements and Contributions in the Performance Prism

Table 10.1. Stakeholder Contributions and Requirements According to the Performance Prism

Organization Needs | Stakeholder Needs |

|---|---|

. . . from investors

| Investors need from the organization:

|

. . . from customers

| Customers need from the organization:

|

. . . from employees

| Employees need from the organization:

|

. . . from suppliers

| Suppliers need from the organization:

|

. . . from regulators

| Regulators want from the organization:

|

. . . from the community

| Communities want from the organization:

|

There is an interesting dynamic between shareholders, the organization, and its other stakeholders. We may think there is no dilemma—after all, it is a common view that the goal of the organization is to maximize shareholder value. But shareholders, whether they are acting in the short or long term, are looking to maximize their returns, which is not necessarily the same as optimizing the performance of the organization. Further, in terms of the Performance Prism, shareholders, supplying capital, are only one necessary type of stakeholder. And if you follow the visualization in Figure 10.1, shareholders are not the central stakeholders in the performance network. In fact, optimization toward shareholder value creates stakeholder dilemmas, as their requirements are disregarded. Investors may press for short-term layoffs, whereas you know a brain-drain will cause issues in the longer term. Investors may focus on immediate improvement of working capital, leading to upsetting customers when collecting invoices is done in an overly aggressive manner. Investors may see corporate social responsibility as frivolous, whereas society sees it as mandatory. It is best if such dilemmas are solved. In order to have a sustainable business, one of the most important tasks of senior management is to reconcile the dilemmas between all relevant stakeholders—the interorganizational dilemmas.[60]

How is this done? No differently than with the other you-and-me dilemmas we have discussed. First, the organization needs to examine its motives. What is it trying to achieve with a specific stakeholder relationship? Different relationships have different intensities. Some relationships are not very strategic, and there are low switching costs. Outsourcing certain forms of logistics, the cleaning service, or the cafeteria is a very transactional decision. Boiled down to its essence, it is "not being bothered too much" that drives the success of the relationship. One notch up, what we might expect from other business relationships is added value. We would like to establish an integrated supply chain with our preferred suppliers. We would like to get close to our customers. We would like to invest in employee education together with the unions. In these cases, switching costs are high. Finally, there are relationships based on co-innovation. Both parties go to market with a joint product or service. Our motives are to grow a business together. Problems and dilemmas arise when the parties do not have the same understanding of the relationship. Opening up to the unions to improve relationships can be a true dilemma if we expect to be treated transactionally in return. Suppliers may not be willing to invest in value chain integration if they believe it will only lead to more dependency and less of a negotiating position. Open and honest communication about both stakeholder contributions and requirements is needed. Then find ways to reconcile any differences that are found. Some retailers have insight into the margins of their suppliers, making sure the relationship stays profitable for both. Some car manufacturers have business improvement teams that suppliers can use to lower their costs. Both suppliers and manufacturer benefit. Some oil companies have established activist group boards in which they actively seek the opinion and advice of pressure groups.

The Performance Prism helps us define those reciprocal relationships, and even guides us in telling how to manage those relationships. However, one thing is missing: It does not help us solve stakeholder dilemmas. The Performance Prism merely states the themes that need to be managed. To successfully reconcile conflicting requirements between the organization and its stakeholders, and among stakeholders surrounding the organization, we need to align the different value propositions.

Strategy is the glue that aims to build and deliver a consistent and distinctive value proposition to your target market.[189] A value proposition is "what we promise to do for you." Stakeholder alignment could be defined as the common understanding of a value proposition. The moment there is no common understanding of that purpose, the stakeholder relationships and consequently the long-term success of the organization are in danger. It is the task of each organization to manage its stakeholder relationships and the alignment of the value proposition.

Kim and Mauborgne argue for the alignment of three value propositions.[190] They state that "a strategy's success hinges on the development and alignment of three propositions: (1) a value proposition that attracts buyers; (2) a profit proposition that enables the company to make money out of the value proposition; and (3) a people proposition that motivates those working for or with the company to execute the strategy." Why not extend the concept of the value proposition to all stakeholders? The promise of what to achieve for investors is commonly known as the investor value proposition (which is different from a profit proposition, as this serves the organization itself). A less commonly accepted term would be a supplier value proposition, stating what the organization promises to achieve for its suppliers. This may seem strange at first. They are suppliers; what they require is being paid on time. What else is there to it? However, there is logic in this concept. If an organization requires the contribution of its suppliers in order to live up to the customer value proposition, it needs to reciprocate. Unless the switching cost to another supplier is negligible, firms need to mind the requirements of the supplier for sustainable success.

The value propositions to all stakeholders need to align. In a transparent world, promising customers to be reliable while at the same time treating suppliers badly impacts the firm's image and authenticity.[191] Promising the shareholders high returns while the margin on the core business does not support that leads to dysfunctional organizational behavior. Many of the corporate scandals in the early 2000s and business failures in the economic crisis of the late 2000s were caused by putting more emphasis on using the company as an instrument of the stock market and making money there, instead of minding the core business. Think of the supermarket chain that treated its operating companies as cash cows to finance even more acquisitions, or the car manufacturer that made more money trading shares of a competitor in pursuit of acquiring that company than the profit from actual car sales.

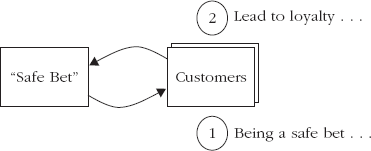

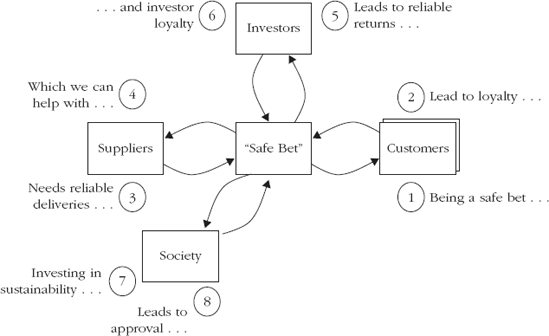

To see how a stakeholder alignment map could look and how it is built, let us consider an example of a food processing firm. Let us assume its value proposition is very customer-centric, to avoid commodization. Many food processing firms employ food technologists to work with customers to ensure the best use of the products. At the same time, utmost attention is paid to the consistent quality of products. In other words, its customer value proposition is being a safe bet for its customers. See Figure 10.2.

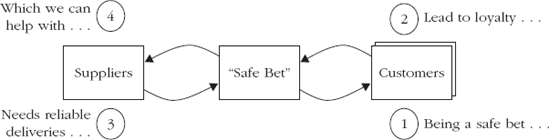

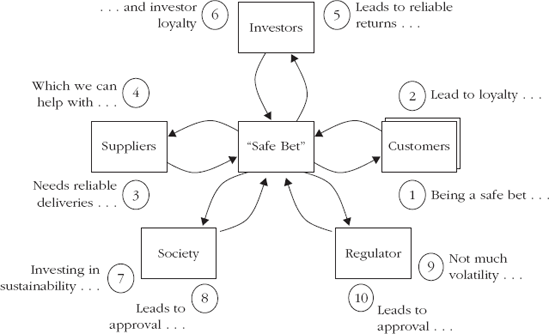

However, organizations should realize their value is broader than their customer value proposition. Companies for instance also have a supplier value proposition, what its promise is to its customers. In the example of the food processing company, it should pay a fair price to its suppliers, and it should pay in time, but more is possible. Some firms in the agricultural/foods markets are known to help their suppliers (farmers) when there are crop issues due to unforeseen weather circumstances. This can be financial aid or to provide other services, helping farmers improve productivity and efficiency[61]. This supplier value proposition can be summarized as being a safe bet. See Figure 10.3.

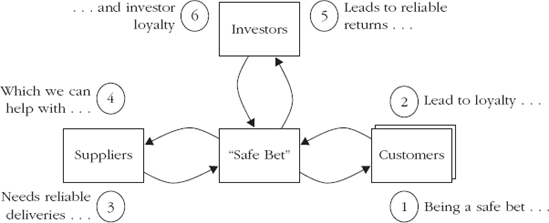

The investor value proposition usually is very straightforward, to provide a competitive shareholder return. The returns of the food processing company may not be as high as in other industries, but instead they may be relatively stable. In other words, they could be a safe bet in the portfolio of investors. See Figure 10.4.

Companies are part of society as well. They need to show they are responsible citizens. By for instance investing in green technology, encouraging suppliers to do the same, and through products making customers greener, companies can create a high level of societal approval. This creates more stability, which is appreciated by investors and customers. See Figure 10.5.

Also, regulators should be considered. As our food processing company is in control of its value chain, does not have a lot of volatility coming from investors and shareholders, and treats its environment with care, it will not easily get the regulators on its back. This leads to a consistent press and image, which is appreciated by customers, suppliers, investors, and society. See Figure 10.6.

It seems a tall order, not only stretching intraorganizational dilemmas, but also managing all stakeholder contributions and requirements. You probably have your hands full managing your own organization as it is. How can all this be managed at the same time? The reality is that there is no such thing as a perfect world. I do not believe in guaranteed sustainability, or being a high-performance organization as a final stage in an organization's maturity. Again, organizations are like living organisms. They strive for survival, but it is a constant struggle. The moment you focus on investors, there is the risk of taking your eyes off the customers. Investments in process improvement may shift your attention away from innovation. Managing company performance means working in a constantly changing dynamic. You need to keep your options open, as the environment changes. By keeping your options open, change becomes a natural flow. Change is not a process that costs energy and disrupts operations. In fact, it is the other way around: Change is a process that brings energy into the company, because of positive stakeholder interactions and constant reconfirmation. And it is disruption of processes that actually brings change.

By seeking stakeholder alignment, you create synthesis. Our example shows that improvements start to have multiple effects. For instance, improving supplier relationships also improves customer relationships, investor relationships, and all other stakeholder relationships. Synthesis is the process of taking two or more ideas and morphing them into one. That means not only one thing less to manage, but creating a flywheel, a fundamental step forward in improving business performance.

As promised in the Preface, creating options and seeking synthesis are the two keys to dealing with dilemmas. And I believe that dealing with dilemmas is the key to driving an organization's sustainable performance.

[59] Discussion is based on F.A. Buytendijk, Performance Leadership, McGraw-Hill, 2008.

[60] This does not mean that dealing with intraorganizational dilemmas is less important. If the internal organization keeps requiring all of management's attention, there is no time to focus on stakeholder management. And on a more strategic level, if your own organization is not healthy and transparent, how can you expect the same of your stakeholders?

[61] In Germany, some agricultural and community banks are known to even organize farmer's markets to support local communities and the local economy. There is no clear difference between customer and supplier value proposition, the bank offers community value.