CHAPTER 2

The Story of Production Sound

Dialogue is the main element of audiovisual narrative, even of silent movies. Though the voices of the silent film characters were not heard, they spoke to us.

Jerónimo Labrada, academic director

EICTV San Antonio de los Baños, Cuba

Introduction

Most of the challenges facing dialogue editors are the result of decisions made on the set. Location mixers must make choices about sound, story, sample rates, timecode, and note taking, all the while vying with the rest of the crew for precious space and even more precious time. These decisions will irrevocably affect the future of the production tracks and hence your way of working.

You can't undo incorrect sample rates, weird timecode, or improper time base references, but if you equip yourself with a knowledge of production workflows, you'll be better able to respond to the problems that come your way. Since you inherit the fruits of the production, you need to understand how films are shot and how the moviemaking chain of events fits together. This way you can plan postproduction workflows before the shoot, before it's too late to do anything but react to problems.

The way we work today is the offspring of generations of tradition, technological advances, economic pressures, and a good deal of chance. Current cinema workflows are more complicated than ever, and with the development of Digital Cinema shooting, postproduction, and distribution, things appear to be truly out of control. But remember that with each significant new technology in the film industry has come a brief period of bedlam that quickly settled into a state of equilibrium. And usually the pressure to get things back to normal is so great that innovative, creative means are quickly devised to rein in the technology and make things better than ever.

Success Has Many Fathers

Sound recording and motion picture filming grew up at more or less the same time. When Thomas Edison recited “Mary Had a Little Lamb” in 1877 to demonstrate his tinfoil Phonograph,1 a bitter war of innovation, patent fights, and downright thievery was raging in Europe and the United States to come up with methods of photographing and projecting moving pictures. Most initial attempts at displaying motion were inspired by Victorian parlor toys like the Phenakistoscope and later the Zoetrope (a spinning slotted cylinder that contained a series of photographs or drawings); a strobe effect gave the impression of motion when the pictures were viewed through the slots. Enjoyable though those gadgets were, they weren't viable ways to film and project real life.

Auguste and Louis Lumière's public screening of La sortie des ouvriers de l'usine Lumière in 1895 is generally acclaimed as the “birth of cinema,” but, then, Christopher Columbus is credited with discovering America. Believe what you will. La sortie des ouvriers, about a minute long, was a static shot of workers leaving the Lumière plant. Was this really the first film to be shown? Of course not. As early as 1888, Augustin Le Prince was able to film and project motion pictures. And Edison, who long claimed to be the inventor of cinema, was making movies in 1892.

From 1892, Birt Acres and Léon Bouly had been independently improving their motion picture systems and their movies. But Bouly couldn't pay the yearly patent fees for his invention and his license expired, while Acres proved a prodigious inventor and filmmaker but managed to slip into relative obscurity. Meanwhile, Antoine Lumière, father of Auguste and Louis, more or less copied Edison's Kinetoscope while taking advantage of Bouly's lapsed patent. The offspring of this effort was the Lumière Cinématographe,2 a camera, projector, and filmprinter all rolled into one (see Figure 2.1).

The brothers Lumière shot and commercially distributed numerous short actualités, including l'Arrivée d'un train en gare (Arrival of a Train at a Station) and Déjeuner de bébé (Baby's Lunch).

In all fairness, the Lumière family had more going for them than just sharp elbows. By 1895, the world was evidently ready to pay money to see factory workers leaving work or a train arriving at a station. Plus, the Cinématographe was startlingly lightweight and portable compared to its behemoth competitors. Relatively portable Lumière cameras opened the door for innovative filmmakers such as Georges Méliès, who made more than 500 silent films between 1896 and 1914, including A Trip to the Moon and 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea. This marriage of technological advances and new means of expression will thrive (with the occasional family spat) for the rest of film history.

Early Attempts at Sound in Movies

It was clear to all that a method of showing sound and picture together was of great commercial interest. In the late 1880s, Edison and his associate, W.K.L. Dickson, linked the Edison cylinder Phonograph with a larger tube that was slotted much like the Zoetrope. It wasn't elegant, but it did produce synchronized images and sound.3 Georges Demeny, in 1891, claimed to produce a synchronous sound system, but like so many assertions in this time of riotous invention, this proved unfounded.

In 1902, Léon Gaumont filed patents for the Chronophone—a marriage of Cinematograph and Phonograph that provided interlocked filming to a prerecorded soundtrack (see Figure 2.2). His invention was quickly put to work and a new art form emerged.

“Phonoscènes” were short, filmed performances—usually no more than three minutes—of monologues and jokes, but mostly of music. “Synchronous” sound and image were recorded separately, and actors were merely miming

Figure 2.2 Léon Gaumont's Chronophone enabled synchronized playback of prerecorded sounds.

(“lip sync” would be too strong a term). Phonoscènes were wildly popular; these playback performances that preceded MTV by 70 years packed Europe's famous halls until 1917.4 Perhaps the most prolific filmmaker to take advantage of this new technology was Alice Guy-Blaché, who directed hundreds of Phonoscènes over the course of 25 years. She's generally considered to be the first female film director.

Initially there wasn't much setting the Chronophone apart from the pack. Soon, though, Gaumont engineers succeeded in recording live, simultaneous sound—an unrivalled breakthrough. At last something resembling modern sound movies was within reach. Plus, Gaumont had the good sense to place his amplified speaker behind the screen, thus reinforcing the illusion. On the 27th of December, 1910, Gaumont presented his treasure to the French Academy of Sciences.5 The first French actor recorded synchronously was a proudly crowing rooster.6

There were many other attempts to add sound to the ever more popular moving picture, but at least three impediments came between a successful marriage of sound and picture: reliable synchronization, amplification, and the fact that silent pictures were so effective and popular.

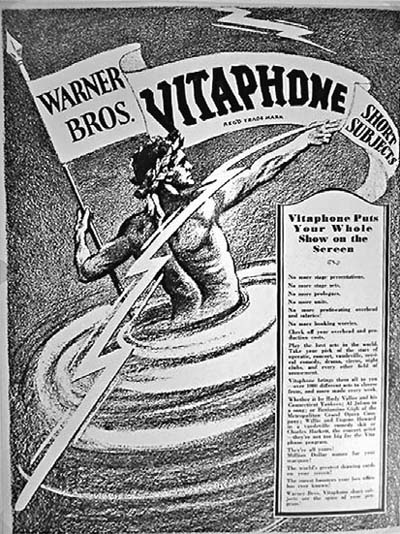

Despite the advances of Gaumont and others, it took a long time to move beyond silent actors mimicking prerecorded playback tracks. Recording live synchronous sound became less and less a gimmick and was accepted widely, but unreliable shellac records remained the distribution medium of choice. Even in the late 1920s, when commercial feature-length talkies were a real possibility, sound playback was usually from a phonograph synchronized to the film projector via belts, pulleys, and cogs. The most successful inter-locked phonograph/projector system was the Vitaphone, made by Western Electric and Bell Laboratories. Although still uncertain of the future of this new-fangled form of entertainment, Warner Brothers produced Vitaphone shorts, which they presented as the way of the future (see Figure 2.3).

Despite its increasing popularity, this double-system playback failed completely in the event of a film break or a skip in the record. The projectionist had no choice but to return to the beginning of the reel. Eugène Augustin Lauste patented a form of optical film soundtrack in 1910, but it would be another 20 years before optical recording was adopted for film sound.7

Amplification of disk or cylinder recordings posed a huge challenge. Early phonographs projected their sounds acoustically rather than through amplification—hardly appropriate for large halls. Turn-of-the-century “acoustic amplifiers” used compressed air to amplify the sounds of the stylus. Through a gating system akin to vacuum tubes—which were first patented in 1906 and brought to market a few years later—acoustic amplifiers enabled sound playback in larger halls, even if the sound reproduced was a bit on the thin side. Ten years later, the German Tri-Ergon sound-on-film system combined American Lee De Forest's Audion vacuum tube with an improved version of Eugène Augustin Lauste's optical sound-on-film recorder, which enabled a sound reader to convert variations in the optical track into a signal that could be amplified and heard by a large audience. This was the beginning of a standard for sound reproduction that would last more than 50 years: Optical sound printed directly onto the film print.

But there was one more hurdle to clear in order to bring sound movies out of the “gee whiz” ghetto and into commercial success. Simply stated, silent pictures worked. By the mid-1920s silent films had established a language and an audience and were rightly considered both entertainment for the masses and an intellectual means of expression. Many filmmakers and film theorists vehemently objected to adding the vulgar novelty of sound to this new but advanced art form. The most famous objection came in the form of the 1928 manifesto, “Sound and Image,” published by Eisenstein, Pudovkin, and Alexandrov.8 They protested that cinema with sound would become a means of displaying the ordinary and the real, rather than reaching to higher meanings through the newly developed art of montage.

It would be naïve to think, however, that the development of cinema sound was held up because of the rantings of a few Soviet intellectuals. In fact, it was the studios themselves that were most opposed to innovation. They had a good thing going, and it was hard for executives to imagine that it would ever change. Silent films were relatively easy and cheap to produce, and studios had invested heavily in the mechanism that enabled them to crank out and distribute them. Also, the costs of refitting movie theaters with sound playback equipment seemed uncomfortably and unnecessarily high.

Yet at the same time, silent films weren't altogether silent or as inexpensive as met the eye. Often, projections were accompanied by live sound effect artists, musicians, singers, or actors, and all these people had to be paid. Studios were interested in reducing these costs, and the most attractive place to start was with the musicians. Devising a way to mechanically play a musical score to a silent film would reduce costs by dismissing the cinema orchestra from every performance. And playback tracks never demand higher wages or go on strike.

Feature-Length Talkies

In 1926, Warner Brothers released Alan Crosland's Don Juan, with a huge score performed by the New York Philharmonic Orchestra. The music was played back—in sync—from a Vitaphone record. Thus was the stage set for a commercially released feature-length talkie to step into history. Crosland's The Jazz Singer, which premiered in October 1927, was actually a standard silent movie with a few lines of spoken dialogue, but still it was a huge moneymaker. It didn't take long for the studios to see the writing on the wall and begin gearing up for sound production and distribution.

Shooting and recording a Vitaphone film was much like producing a live radio show. There was no postproduction, so every sound in a scene had to be recorded live—sound effects, off-screen dialogue, music, everything. Until rerecording became practicable in the 1930s, editing of any kind was all but impossible. And while silent films of the 1920s had developed a light touch and artistic elegance, the new Talkies imprisoned noisy cameras into static soundproof cabinets, out of earshot of the indiscriminating microphones (see Figure 2.4).

Figure 2.4 On the set during a Vitaphone shoot. Cameras were relegated to sound-proofed booths with small windows made of thick glass.

We were back to the unmoving stuffy days of Georges Méliès' unmoving camera. Various technical advances would sort out many of the noise problems, but it would be almost 40 years before filmgoers were to once again experience the freedom and lightness of the silent Tramp.

Postsynchronization was first used in 1929 by King Vidor on the film Hallelujah!9 Freeing the shooting process from the draconian restrictions that early sound recording techniques imposed, it restored some of the grace of the silent era. By the mid-1930s, it was possible to mix several channels of sound without distortion, and postsynchronization of dialogue and other sounds began to allay the fears of those who predicted that sound cinema would inevitably result in purely naturalistic films.

Sound was still recorded optically, however, so it was very tedious and time consuming to edit and manipulate recorded tracks. Blimps were invented to quiet noisy cameras, microphones became more directional, and optical soundtracks were improved and standardized. The sound Moviola was made available in 1930, so there was now a standardized, sophisticated way to edit picture and optical sound film. In 1932, a process of printing a common serial number on synchronized picture tracks and soundtracks was developed. “Edge numbering,” or “rubbering,” allowed accurate logging of film elements and reprinting of edited tracks from their original masters. This system of coding film workprint and sound elements has remained more or less unchanged.

In a brief period of time, movie sound got much better. Arc lights lost their deafening hum, so they could be used on sound pictures. Biased recording was introduced, yielding far quieter tracks. Fine-grain film stock resulted in not only better-looking prints but also finer-resolution optical soundtracks, as did UV optical printing. In 1928, the frequency response of motion picture soundtracks was 100 Hz to 4,000 Hz. Ten years later it was 30 Hz to 10,000 Hz10.

Despite these improvements in sound recording and mixing technology, film sound editing didn't substantively change for more than 20 years. Picture and sound editors worked on Moviolas, later adding flatbed film editing tables such as the Steenbeck, KEM, or console Moviolas. Sound was printed onto 35 mm optical sound film for editing and mixing, and released on 35 mm film with mono optical soundtracks.

With a great deal of muscle from singer Bing Crosby, magnetic tape made inroads into broadcasting in the late 1940s. Artists were no longer tied to studios for live performances that constrained their freedom, stifled their artistic growth, and limited their income. It was just a matter of time before it would revolutionize filmmaking.

The Modern Era

In 1958 magnetic recording for cinema came of age and everything changed. Stefan Kudelski introduced the Nagra III battery-operated transistorized field tape recorder, which with its “Neo-Pilot” sync system became the de facto standard of the film industry.11 (See Figure 2.5.)

Soon production sound was being transferred to 35 mm magnetic film, mag stripe, which could be easily handled, coded, edited, and retransferred as needed. Dialogue and effects editors were now free to manipulate tracks as never before. During the mix, edited dialogue, effects and backgrounds,

Figure 2.5 The Nagra III, launched in 1958, was a monaural recorder that changed the way films are made. (Drawing by Rick Bissell)

Foley, and music elements were combined and recorded onto yet more 35 mm magnetic film (fullcoat). (This system continues today on films edited mechanically.) With sound elements on mag, there was no real technical limit to the complexity of the sound design or even the number of tracks, although the cumulative hiss from the mag discouraged playing too many tracks at once. When Dolby noise reduction was adopted for film optical tracks in 1975, even this limitation was surmounted.

A new format, Dolby Stereo, was born. Not only were films significantly quieter on the production and postproduction ends of things, but this new format enabled encoding four channels onto a two-channel optical film track. Behind the screen were left and right speakers to create stereo sound. And just as Gaumont placed his Chronophone behind the screen in order to “plant” the sound in the center of the image, so too did Dolby Stereo. The format added an additional mono surround channel that hugs the side and rear walls. Although Dolby Stereo was ill-suited to fly a helicopter from left rear to front right, it was good enough to make Star Wars a powerful experience. The Jazz Singer convinced theater owners to invest in sound technology. Fifty years later, Star Wars did the same for surround.

Dolby did more than make films quiet and big-sounding. It brought about a near-universal standard that ended the gnawing question that had forever plagued the movie business: “Good mix, but what will it sound like in the theater?” By enforcing standards throughout the postproduction workflow— mix, lab, and theater—mixers could finally relax. What you hear at the premiere will be very, very close to the soundtrack made in the mix.

In the 1990s, bigger, better, flashier film sound distribution formats emerged, all within a period of just over one year. Batman Returns (1992) heralded Dolby Digital, followed six months later by DTS with Jurassic Park. SDDS was launched with Last Action Hero in 1993. Dolby and SDDS print their soundtracks directly on the film print—the process dating from the time of the Talkies. The soundtrack for DTS lives on a separate CD synchronized to a timecode track on the film. A very sophisticated Vitaphone. Analogue optical tracks are all but abandoned, used only as a backup for its much sexier younger sibling: Dolby Digital.

Twenty years later, film itself is being marginalized. Digital Cinema cameras whose resolution matches or exceeds that of film are seen on more and more sets, and most “films” we see never touch celluloid. Conforming, grading, and mastering are carried out digitally. And except in the smallest of markets, movies are projected from a digital file. For us, this technology has resulted in one immense change: The end of the Dolby standard. Filmmakers are now free to mix to whatever standard they want—or none at all—which means that the norms established in the 1970s are no longer de rigueur.

In the next chapter we'll look at how changes in technology have altered the way we work. Much of what has changed in recent years doesn't affect you, the dialogue editor. But there's one revolution that has affected every one of us, and which turned our industry on its head.

Editing is Forever Changed

Recording on analogue tape, editing sound and picture on mag stripe, mixing to fullcoat, and releasing on a standardized print served the film industry for more than 40 years. It was predictable, stable, and universal, and its hunger for labor kept apprentices and assistants—many of whom would be the next generation of editors—near the action. Then, once again, it all changed. Enter nonlinear picture editors (NLEs) and digital audio workstations (DAWs).

Now, for far less than the price of a car, you can have unrivaled editing, processing, and management power in a small computer. You can make changes over and over, painlessly creating alternate versions of your work. There's no getting around the fact that the technology is massively better than it was a generation ago, which means that you're much more empowered to make your own choices.

What was once a well understood, widely accepted process has been given a huge dose of democracy, if not anarchy. The way we work has changed in a revolutionary way, not just in a few evolutionary adjustments. Crews are smaller and roles are less defined, and even the basic workflow is no longer so basic. The way you work now depends on where you live, plus 1,000 other peculiar variables.

_______________

1. Biographies of Thomas Edison aren't hard to come by, but a rich and simple source of Edison history and archival material is the U.S. Library of Congress website, which has a section devoted to him. Edison phonograph sound clips and movie excerpts are available, as are countless historical documents (http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/edhtml/edhome.html).

2. Tjitte de Vries. “The Cinématographe Lumière: A Myth?” Photohistorical Magazine of the Photographic Society of The Netherlands (1995, www.xs4all.nl/çwichm/myth.html).

3. Mark Ulano. “Moving Pictures That Talk, Part 2: The Movies Are Born a Child of the Phonograph” (www.filmsound.org/ulano/index.html).

4. Thomas Louis Jacques Schmitt. “Phonoscénes Gaumont,” Du temps des cerises aux feuilles mortes, 2010 (www.dutempsdescerisesauxfeuillesmortes.net/textes_divers/phonoscenes/phonoscenes.htm).

5. Martin Barnier, “Présentation de son chronophone par Léon Gaumont,” Archives de France, 2010.

6. Gaumont's choice was no accident. It was a snub at film equipment manufacturer Pathé—Gaumont's arch rival. The Pathé logo was a crowing cock.

7. David A. Cook. A History of Narrative Film (New York: Norton, 1981, pp. 241–44).

8. Cook, 1981, pp. 265–66.

9. Cook, 1981, p. 268.

10. Elisabeth Weis and John Belton, eds. Film Sound: Theory and Practice (New York: Columbia University Press, 1985, p. 67).

11. Audio Engineering Society (www.aes.org/aeshc/docs/audio.history.timeline.html).