CHAPTER 5

SEEING WITH A MOVIEMAKER'S EYE

The four study projects in this chapter will make you familiar with the essentials of composition, editing, script analysis, and lighting. Collectively they yield the basics of seeing with a moviemaker's eye and will be immensely useful to your confidence when you begin directing.

PROJECT 5–1: PICTURE COMPOSITION ANALYSIS

A stimulating and highly productive way to investigate composition is to do so with several other people or as a class. Though what follows is written for a study group, you can do it solo if circumstances so dictate.

Equipment Required: For static composition, a slide projector and/or an overhead projector to enlarge graphics are best but not indispensable. For dynamic composition you will need a video or DVD player.

Object: To learn the composition of visual elements by studying how the eye reacts to a static composition and then how it handles dynamic composition, that is, composition during movement.

Study Materials: For static composition, a book of figurative painting reproductions (best used under an overhead projector so you have a big image to scan), or better, a dozen or more 35 mm art slides, also projected as large images. Slides of Impressionist paintings are good, but the more eclectic your collection, the better. For dynamic composition, use any visually interesting sequences from a favorite movie, though any Eisenstein movie will be ideal.

ANALYSIS FORMAT

In a class setting it's important to keep a discussion going, but if you are working alone, notes or sketches are a good way to log what you discover. Help from books on composition is not easily gained because many texts make composition seem intimidating or formulaic and may be difficult to apply to the moving image. Sometimes rules prevent seeing rather than promoting it, so trust your eye to see what is really there and use your own non-specialist vocabulary to describe it.

STRATEGY FOR STUDY

If you are leading a group, you will need to explain what is wanted something like this:

We're doing this to discover how each person's visual perception actually works. I'll put a picture up on the screen. Notice where your eye goes in the composition first, and then what course it takes as you examine the rest of the picture. After about 15 seconds I'll ask someone to describe what path his eye followed. You don't need any special jargon, just let your responses come from the specifics of each picture. Please avoid the temptation to look for a story in the picture or to guess what the picture is “about,” even when it suggests a story.

With each new image, pick a new person to comment. Because not everyone's eye responds the same way, there will be interesting discussions about the variations. There will usually be a great deal of agreement, so everyone is led to formulate ideas about visual reflexes and about what compositional components the eye finds attractive and engrossing. It is good to start simply and graduate to more abstract images, and then even to completely abstract ones. Many people, relieved of the burden of deciding a picture's “subject,” can begin to enjoy a Kandinsky, a Mondrian, or a Pollock for itself, without fuming over whether or not it is really art. After about an hour of pictures and discussion, encourage your group to frame their own guidelines for composing images.

After the group has formed some ideas and gained confidence from analyzing paintings, I usually show both good and bad photos. Photography, less obviously contrived than painting, tends to be accepted less critically. This is a good moment to uncover in striking photography just how many classical elements arise from what first appeared to be a straight record of life.

Here are questions to help you discover ways to see more critically. They can be applied after seeing a number of paintings or photos, or you could direct the group's attention to each question's area as it becomes relevant.

STATIC COMPOSITION

- After your eye has taken in the whole, review its starting point. Why did it go to that point in the picture? (Common reasons: brightest point in composition, darkest place in an otherwise light composition, single area of an arresting color, significant junction of lines creating a focal point.)

- When your eye moved away from its point of first attraction, what did it follow? (Commonly: lines, perhaps actual ones like the line of a fence or an outstretched arm, or inferred lines such as the sightline from one character looking at another. Sometimes the eye simply moves to another significant area in the composition, going from one organized area to another and jumping skittishly across the intervening disorganization.)

- How much movement did your eye make before returning to its starting point?

- What specifically drew your eye to each new place?

- If you trace an imaginary line over the painting to show the route your eye took, what shape do you have? (Sometimes this is a circular pattern and sometimes a triangle or ellipse, but it can be many shapes. Any shape at all can reveal an alternative organization that helps you see beyond the wretched and dominating idea that every picture tells a story.)

- Are there any places along your imaginary line that seem specially charged with energy? (These are often sightlines: between the Virgin's eyes and her baby's, between a guitarist's and his hand on the strings, between two field workers, one of whom is facing away.)

- How would you characterize the compositional movement? (For example, geometrical, repetitive textures, swirling, falling inward, symmetrically divided down the middle, flowing diagonally, etc. Making a translation from one medium to another—in this case from the visual to the verbal—always helps you discover what is truly there.)

- What parts, if any, do the following play in a particular picture?

- repetition

- parallels

- convergence

- divergence

- curves

- straight lines

- strong verticals

- strong horizontals

- strong diagonals

- textures

- non-naturalistic coloring

- light and shade

- human figures

- How is depth suggested? (This is an ever-present problem for the director of photography (DP) who, if inexperienced, is liable to take what I think of as the firing squad approach: that is, placing the human subjects against a flat background and shooting them. Unless there is something to create different planes, like a wall angling away from the foreground to suggest a receding space, the screen is like a painter's canvas and looks what it really is—two-dimensional.)

- How are the individuality and mood of the human subjects expressed? (This is commonly through facial expression and body language, of course. But more interesting are the juxtapositions the painter makes of person to person, person to surroundings, or people inside a total design.)

- How is space arranged on either side of a human subject, particularly in portraits? (Usually in profiles there is lead space, that is, more space in front of the person than behind them, as if in response to our need to see what the person sees.)

- How much headroom is given above a person, particularly in a close-up? (Sometimes the edge of a frame cuts off the top of a head or may not show one head at all in a group shot.)

- How often and how deliberately are people and objects placed at the margins of the picture so you have to imagine what is cut off? (By demonstrating the frame's restriction you can make the viewer's imagination supply what is beyond the edges of the “window.”)

VISUAL RHYTHM: HOW DURATION AFFECTS PERCEPTION

So far I have stressed the idea of an immediate, instinctual response to the organization of an image. When you show a series of slides without comment, you move to a new image after sufficient time for the eye to absorb each picture. Some pictures require longer than others. For a movie audience, unless shots are held for an unusual length of time, as pioneered in Antonioni's L'Avventura (1960), this is how an audience must deal with each new shot in a film.

Unlike responding to a photograph or painting, which can be studied thoughtfully and at leisure, the filmgoer must interpret the image within an unremitting and preordained forward movement in time. It is like reading a poster on the side of a moving bus: if the words and images cannot be assimilated in the given time, the inscription goes past without being understood. If, however, the bus is crawling in a traffic jam, you may have time to absorb and become critical or even rejecting of the poster.

This tells us that there is an optimum duration for each shot to stay on the screen. It depends on the complexity of a shot's content and form and how hard the viewer must work to extract its significance and intended meaning. An invisible third factor also affects ideal shot duration—that of expectation. The audience may work fast at interpreting each new image, or slowly, depending on how much time the film has allowed for interpreting preceding shots.

The principle by which a shot's duration is determined according to content, form, significance, and expectation is called visual rhythm. A filmmaker, like a musician, can either relax or intensify a visual rhythm, and this has consequences for the cutting rate and the ideal tempo of camera movements.

Ideal films for studying compositional relationships in film and visual rhythm are classics by the Russian director Sergei Eisenstein, such as The Battleship Potemkin (1925), Que Viva Mexico (1931–1932), Alexander Nevsky (1938), and Ivan the Terrible (1944–1946). Eisenstein's origins as a theater designer made him very aware of the impact upon an audience of musical and visual design. His sketchbooks show how carefully he designed everything in each shot, down to the costumes. More recent films with a strong sense of design are Ingmar Bergman's The Seventh Seal (1956), Stanley Kubrick's A Clockwork Orange (1971), and David Lynch's Blue Velvet (1986).

Designer's sketches and the comic strip are the precursor of the storyboard (see example in Figure 6-2 in the next chapter), which is much used by ad agencies and conservative elements in the film industry to lock down what each new frame will convey. Storyboarding is particularly helpful for the inexperienced, even when your artistry is as lousy as mine and doesn't run much beyond stick figures.

DYNAMIC COMPOSITION

With moving images, more compositional principles come into play. A balanced composition can become disturbingly unbalanced should someone cross the frame, or leave it altogether. Even the turn of a figure's head in the foreground may posit a new eyeline (subject-to-subject axis), which in turn demands a compositionalrebalancing. Then again, zooming in from a wide shot demands reframing because compositionally there is a drastic change, even though the subject is the same.

To study dynamic composition, find a visually interesting sequence, such as the chase in John Ford's Stagecoach (1939) or William Friedkin's The French Connection (1971) or almost any part of Andrew Davis' The Fugitive (1993). Here your VCR's slow-scan function will be very useful. See how many of these aspects you can find:

- Reframing because the subject moved (look for a variety of camera adjustments)

- Reframing as a consequence of something or someone entering the frame

- Reframing in anticipation of something or someone entering the frame

- A change in the point of focus to move attention from background to foreground or vice versa. (This changes the texture of significant areas of the composition from hard focus to soft.)

- Strong movement within an otherwise static composition (How many can you find? Across frame, diagonally, from background to foreground, from foreground to background, up frame, down frame, etc. Eisenstein films are full of these compositions.)

In addition, ask yourself the following questions:

- How much do you feel identified with each kind of subject movement? (This is a tricky issue, but in general the nearer you are to the axis of a movement, the more subjective is your sense of involvement).

- How quickly does the camera adjust to a figure who gets up and moves to another place in frame? (Often camera movements are motivated by changes from within the composition, and subject and camera moves are made synchronous, with no clumsy lag or anticipation. When documentary covers spontaneous events, such inaccuracies are normal and signal that nothing is contrived.)

- How often are the camera or the characters blocked (that is, choreographed) to isolate one character? What is the dramatic justification?

- How often is the camera moved or the characters blocked so as to bring two characters back into frame? (Good camerawork, composition, and blocking is always trying to show relatedness. This helps to intensify meanings and ironies and reduces the need to manufacture relationship through editing.)

- How often is composition angled down sightlines and seeing in depth, and how often do sightlines cross the screen and render space as flat? (Point of view often shifts at these junctures from subjective to objective.)

- What do changes of angle and composition make you feel about (or toward) the characters? (Probably you will feel more involved, then more objective.)

- Find several compositions that successfully create depth and define what visual element is responsible. (An obvious one is where the camera is next to a railroad line as a train rushes up and past. Both the perspective revealed by the rails and the movement of the train create depth. In deep shots, different zones of lighting at varying distances from the camera, or zones of hard and soft focus, can also achieve this.)

- How many shots can you find where the camera changes position to include more or different background detail to comment on the foreground subject?

INTERNAL AND EXTERNAL COMPOSITION

So far we have been looking at composition that is internal to each shot. Another form of compositional relationship is the momentary relationship between an outgoing shot and the next, incoming shot. This relationship called external composition, is a hidden part of film language. It is hidden because we are unaware of how much it influences our judgments and expectations.

A common usage for external composition is when a character leaving the frame in the outgoing shot (A) leads the spectator's eye to the very place in shot B where an assassin will emerge in a large and restless crowd. The eye is conducted to the right place in a busy composition.

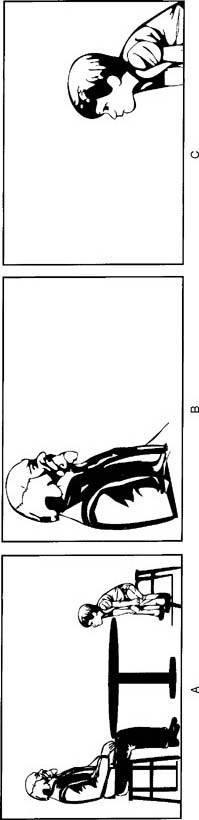

Another example might be the framing of two complementary close shots in which two characters have an intense conversation. The compositions are similar but symmetrically opposed. In Figure 5-1 the two-shot (A) gives a good overall feel of the scene, but man and child are too far away. The close shots, (B) and (C), retain the feel of the scene but effectively cut out the dead space between them. Note that the heads are not centered: each person has lead (rhyming with “feed”) space in front of his face, and this reflects his positioning in the two-shot. The man is high in the frame and looking downward, and the child lower in the frame and looking up—just as in the matching two-shot.

Other aspects will emerge if you apply the questions below to the film sequences you review. Use the slow-scan function to examine compositional relationships at the cutting point. Go backward and forward several times over each cut to be sure you miss nothing. Try these for yourself:

- Where was your point of concentration at the end of the shot? (You can trace where your eye goes by moving your finger around the screen of the monitor. Your last point in the outgoing shot is where your eye enters the composition of the incoming shot. Notice how shot duration determines the distance the eye travels in exploring the shot. This means that on top of what we have already established about shot length, it is also a factor in external composition.)

- What kinds of symmetry exist between complementary shots (that is, between shots designed to be intercut)?

- What is the relationship between two different-sized shots of the same subject that are designed to cut together? (This is a revealing one; the inexperienced

camera operator will produce medium shots and close shots that cut poorly because the placements of the subject are incompatible.)

- Examine a match cut very slowly and see if there is any overlap. (Especially where there is relatively fast action, a match cut, to look smooth, needs about four frames of the action repeated on the incoming shot. This is because the eye does not register the first three or four frames of any new image. This built-in perceptual lag means that when you cut to the beat of music, the only way to make the cuts look in sync with the beat is to make each cut around three or four frames before the actual beat point.)

- Find visual comparisons in external composition that make a Storyteller's comment (for instance, cut from a pair of eyes to car headlights approaching at night, from a dockside crane to a man feeding birds with arm outstretched, etc.)

COMPOSITION, FORM, AND FUNCTION

Form is the manner in which content is presented, and visual composition as part of form is not mere embellishment but a vital element in communication. While it interests and even delights the eye, good composition is an important organizing force when used to dramatize relativity and relationship, and to project ideas. Superior composition not only makes the subject (content) accessible, it heightens the viewer's perceptions and stimulates his or her imaginative involvement, like language from the pen of a good poet.

I believe that form follows function, and that you should involve yourself with content before looking for the appropriate form to best communicate it. Another way of working, which comes from being more interested in language than content, is to decide on a form and then look for an appropriate subject. The difference is one of purpose and temperament. Content, form, structure, and style are analyzed in greater detail in Chapters 12 to 16.

So far we have looked at pictorial composition, but a film's sound track is also a composition and is critically important to a film's overall impact. The study of sound is included in the next editing study project.

PROJECT 5–2: EDITING ANALYSIS

Equipment Required: VCR or DVD player as in Project 1

Objective: To produce a detailed analysis of a portion of film using standard abbreviations and terminology; to analyze the way a film is constructed; and to distinguish the conventions of film language so they can be used confidently

Study Materials: Any well-made feature film containing dialogue scenes and processes that have clear beginnings, middles, and ends will do, but I recommend these films for their excellent development of characters and settings:

- Terence Malick's Days of Heaven (1978) for its awe-inspiring cinematography of the Texas landscape, its exploration of space and loneliness, and its unusual and effective pacing. The film uses the younger sister Linda as a narrator.

- Peter Weir's Witness (1985) for its classically shot dialogue scenes, its exploration of love between mismatched cultures, and the superb Amish work sequences.

- Stephen Daldry's Billy Elliot (2000) has interesting character studies and dynamic dance sequences.

FIRST VIEWING

First, see the whole film without stopping, and then see it a second time before you attempt any analysis. Write down all the strong feelings the film evoked, paying no attention to order. Note from memory which sequences sparked those feelings. You may have an additional sequence or two that intrigued you as a piece of virtuoso storytelling. Note these down, too, but whatever you study should be something that hits you at an emotional, rather than a merely intellectual, level.

ANALYSIS FORMAT

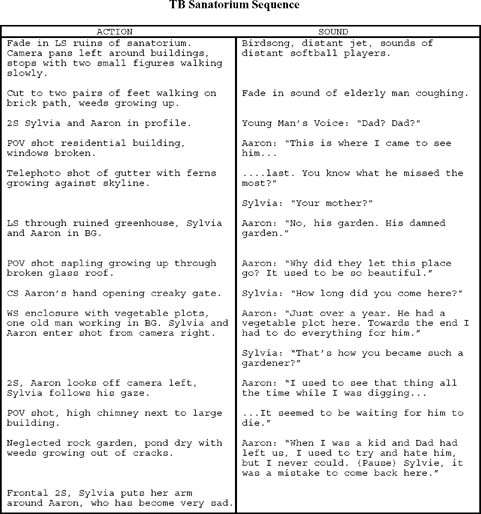

What you write down will be displayed on paper in split page format, also known as TV script format. All visuals are placed on the left half of the page and all sound occupies the right half (Figure 5-2).

First, transcribe the picture and dialogue—shot by shot and word by word— as they relate to each other. Your draft transcript should be written with wide line spacing on numerous sheets of paper so you can insert additional information on subsequent passes. Once this basic information is on paper, you can turn to such things as shot transitions, internal and external composition of shots, screen direction, camera movements, opticals (such as fades, dissolves, superimpositions), sound effects, and the use of music. You will need to make a number of shot-by-shot passes through your chosen sequence, dealing with one or two aspects of the content and form at a time.

Because your objective is to extract the maximum amount of information about an interesting passage of film language, it is better to do a short sequence (two to four minutes) very thoroughly than a long one superficially. Script formats, whether split page or screenplay, show only what can be seen and heard. Some of your notes (for example, on the mood a shot evokes) will clutter the functional simplicity of your transcript, so keep them separately.

MAKING AND USING A FLOOR PLAN

For a sequence containing a dialogue exchange, make a floor plan (also called a ground plan) sketch (Figure 5-3). In the example, the character Eric enters, stands in front of William, goes to the phone, picks up a book from the table, looks out the window, and then sits on the couch. The whole action has been covered by three camera positions. Making a floor plan for a sequence allows you to: recreate what a whole room or location layout looks like, record how the characters move around, and decide how the camera is placed. This will help you decide where to place your own camera in the future, and it reveals how little of an environment needs to be shown for the audience to create the rest in their imaginations. This is the co-creation discussed earlier in Chapter 1.

STRATEGY FOR STUDY

Your split page script should contain:

1. Action-side descriptions of

a. each shot (who, what, when, where)

b. its action content

c. camera movements

d. optical effects (fades, dissolves, etc.)

2. Sound-side descriptions of:

a. dialogue, word for word

b. positioning of dialogue relative to the action

c. music starting and stopping points

d. featured sound effects (that is, other than synchronous, or “sync” sound)

Sound that is native to the location is called diegetic sound. Non-diegetic sound is that which has been applied as counterpoint, for example, the sound of a loud heartbeat placed over a man trapped in an elevator.

Very important: Read from the film rather than reading into it. Film is a complex and deceptive medium; like a glib and clever acquaintance, it can make you uneasy about your perceptions and too ready to accept what should be seen or should be felt. Recognize what the film made you feel, then trace your impressions to what can actually be seen and heard in the film. To avoid overload, scrutinize the sequence during each pass on just a few of the aspects listed below. Try to find at least one example of everything so you understand the concepts at work. Though I have listed them in a logical order for inquiry, reorder my list if you prefer.

First Impressions

What was the progression of feelings you had watching the sequence?

- How long is the sequence (minutes and seconds)?

- What determines the sequence's beginning and ending points?

- How many picture cuts does it contain?

- Is its span determined by:

Being at one location?

Being a continuous segment of time?

A particular mood?

The stages of a process?

Something else?

The duration of each shot and how often the camera angle is changed may be aspects of the genre (what type of film it is) or a director's particular style, or suggested by the sequence's content. Try to decide whether the content or its treatment is determining the frequency of cutting.

Use of Camera

- How many different motivations can you find for the camera to make a movement?

- Does the camera follow the movement of a character?

- Does a car or other moving object permit the camera to pan the length of the street so that camera movement seems to arise from action in the frame?

- How does the camera lay out a landscape or a scene's geography for the audience?

- When does the camera move in closer to intensify our relationship with someone or something?

- When does the camera move away from someone or something so we see more objectively?

- Does the camera reveal other significant information by moving?

- Is the move really a reframing to accommodate a rearrangement of characters?

- Is the move a reaction—panning to a new speaker, for instance?

- What else might be responsible for motivating this particular camera move?

- When is the camera used subjectively?

- When do we directly experience a character's point of view?

- Are there special signs that the camera is seeing subjectively? (For example, an unsteady handheld camera used in a combat film to create a running soldier's point of view.)

- What is the dramatic justification for this?

- Are there changes in camera height?

- Are they made to accommodate subject matter?

- Do they make you see in a certain way?

- Are they done for other reasons?

Use of Sound

- What sound perspectives are used?

Do they complement camera position? (Use a near microphone for close shots and far from microphone for longer shots, thus replicating camera perspective.)

Do they counterpoint camera perspective? (Robert Altman's films often give us the intimate conversation of two characters seen distantly traversing a large landscape.)

Are sound perspectives uniformly intimate (as with a narration, or with voice-over and thoughts voices that function as a character's interior monologue) or are they varied?

- How are particular sound effects used?

To build atmosphere and mood?

As punctuation?

To motivate a cut (next sequence's sound rises until we cut to it)?

As a narrative device (horn honks so woman gets up and goes to window where she discovers her sister is making a surprise visit)?

To build, sustain, or diffuse tension?

To provide rhythm (meal prepared in a montage of brief shots to the rhythmic sound of a man splitting logs; last shot, man and woman sit down to meal)?

To create uncertainty?

Other situations?

Editing

What motivates each cut?

- Is there an action match to carry the cut?

- Is there a compositional relationship between the two shots that makes the cut interesting and worthwhile?

- Is there a movement relationship that carries the cut (for example, cut from car moving left-to-right to boat moving left-to-right)?

- Does someone or something leave the frame (making us expect a new frame)?

- Does someone or something fill the frame, blanking it out and permitting a cut to another frame that starts blanked and then clears?

- Does someone or something enter the frame and demand closer attention?

- Are we cutting to follow someone's eyeline to see what they see?

- Is there a sound, or a line, that demands that we see the source?

- Are we cutting to show the effect on a listener? What defines the right moment to cut?

- Are we cutting to a speaker at a particular moment that is visually revealing? What defines that moment?

- If the cut intensifies our attention, what justifies that?

- If the cut relaxes and objectifies our attention, what justifies that?

- Is the cut to a parallel activity (that is, something going on simultaneously)?

- Is there some sort of comparison or irony being set up through juxtaposition?

- Are we cutting to a rhythm (perhaps to an effect, music, or the cadences of speech)?

- Other reasons?

What is the relationship of words to images?

- Does what is shown illustrate what is said?

- Is there a difference, and therefore a counterpoint, between what is shown and what is heard?

- Is there a meaningful contradiction between what is said and what is shown?

- Does what is said come from another time frame (for example, a character's memory or a comment on something in the past)?

- Is there a point at which words are used to move us forward or backward in time? (That is, can you pinpoint a change of tense in the film's grammar? This might be done visually, as in the old cliché of autumn leaves falling after we have seen summer scenes.)

- Any others?

When a line overlaps a picture cut, what is the impact of the first strong word on the new image?

- Does it help identify the new image?

- Does it give the image a particular emphasis or interpretation?

- Is the effect expected (satisfying, perhaps) or unexpected (maybe a shock)?

- Is there a deliberate contradiction?

- Other effects?

Examine at least three music sections. Where and how is music used?

- How is it initiated (often when characters or story begin some kind of motion)?

- What does the music suggest by its texture, instrumentation, etc.?

- How is it finished (often when characters or story arrive at a new location)?

- What comment is it making? (Ironic? Sympathetic? Lyrical? Revealing the inner state of a character or situation? Other?)

- From what other sound (if any) does it emerge (or segue)?

- What other sound does it merge (or segue) into as its close?

Blocking is a term for the way actors and camera move in relation to each other and to the set. As discussed earlier, point of view seldom means whose literal eyelines the audience shares. More often it refers to whose reality the viewer most identifies with at any given time. The director's underlying statement is largely achieved through the handling of point of view, yet how this is done can be deceptive unless you look very carefully. A film, like a novel, can have a main point of view associated with a main, point-of-view character and also expose us to multiple, conflicting points of view anchored in other characters.

Sometimes there is one central character, and one point of view, like the mentally handicapped Karl in Billy Bob Thornton's Slingblade (1997). Or there may be a couple whose relationship is at issue, as in Woody Allen's Annie Hall (1977). Successive scenes may be devoted to establishing alternate characters' dilemmas and conflicts. Altman's Nashville (1975) has nearly two dozen central characters, and the film's focus is the music town of Nashville being their point of convergence and their confrontation with change. Here, evidently, we find the characters are part of a pattern, and the pattern itself is surely an authorial point of view that questions the way people subscribe to their own destiny. Both Quentin Tarantino's Pulp Fiction (1994) and Robert Altman's Short Cuts (1993) use serpentine storylines with characters who come and go and appear in different permutations. Each sequence is liable to have a different point-of-view character. Both films deal with the style and texture of groups, and their time and place.

Following are some ways to dig into a sequence to establish how it covertly structures the way we see and react to its characters. But first, a word of caution. Point of view is a complex notion that can only be specified confidently after considering the aims and tone of the whole work. Taking a magnifying glass to one sequence may be misleading unless you use it as an example to verify and justify your overall hypothesis. How the camera is used, the frequency with which one character's feelings are revealed, the amount of development he or she goes through, the vibrancy of the acting—all these factors could play a part in enlisting our sympathy and interest.

In your sequence for study, to whom, at different times, is the dialogue or narration addressed?

- By one character to another?

- By one character to himself (thinking aloud, reading diary or letter)?

- Directly to the audience (narration, interview, prepared statement)?

- Other situations?

How many camera positions were used? (Use your floor plan.)

- Show basic camera positions and label them A, B, C, etc.

- Show camera dollying movements with dotted line leading to new position.

- Mark shots in your log with the appropriate A, B, C camera angles.

- Notice how the camera stays to one side of the subject-to-subject axis (an imaginary line between characters that the camera usually avoids crossing) to keep characters facing in the same screen direction from shot to shot. When this principle is broken, it is called crossing the line, crossing the axis, or breaking the 180-degree rule, and it has the effect of temporarily disrupting the audience's sense of spatial relationships.

- How often is the camera close to the crucial axis between characters?

- How often does the camera subjectively share a character's eyeline?

- When and why does it take an objective stance to the situation (that is, either a distanced viewpoint, or one independent of eyelines)?

Character and Camera Blocking

How did the characters and camera move in the scene? To the location and camera movement sketch you have made, add dotted lines to show the characters' movements (called blocking). Use different colors for clarity.

- What points of view did the author engage us in?

- Whose story is this sequence, if you go by gut reaction?

- Considering the camera angles on each character, with whose point of view were you led to sympathize?

- How many psychological viewpoints did you share? (Some may have been momentary or fragmentary, and perhaps in contradiction to what you were seeing.)

- Are the audience's sympathies structured by camera and editing, or more by acting or the situation itself?

FICTION AND THE DOCUMENTARY

Most of these analytical questions apply equally to the documentary film because the two forms have much in common. This is more than a similarity in film language, for some of the important questions cannot be applied to most nature, travelogue, industrial, or educational films. These other genres generally lack what distinguishes the fictional and documentary forms—an authorial perspective. That is, they often lack a point of view, a changing dramatic pressure, and a critical perspective expressed about what it means to be human.

This critical relationship to the characters and their world is crucial to providing the feeling of a distinctly human sensibility unifying the events it shows, even though (and we must never forget this) the making of a film is collaborative. We sense the presence of a Storyteller's sympathy and intelligence, so what in lesser hands might be technical or formulaic becomes vibrantly human. This kind of vision is the best sort of leadership, for without egoism and by example it invites us to see a familiar world with new eyes.

PROJECT 5–3: A SCRIPTED SCENE COMPARED WITH THE FILMED OUTCOME

Objective: To study the relationship between the blueprint script and the filmed product.

Study Materials: A film script and the finished film made from it on videotape. Don't look at the film until you have planned your own version from the text. The script must be the original screenplay and not a release script (that is, not a transcript made from a finished film). A suitable script can be found in Pauline Kael's The Citizen Kane Book: Raising Kane (New York, Limelight Editions, 1984). Another is Harold Pinter's The French Lieutenant's Woman: A Screenplay (Boston, Little, Brown, and Co., 1981. The latter has an absorbing foreword by John Fowles, the author of the original novel. It tells the story of the adaptation and describes, from a novelist's point of view, what is involved when your novel makes the transition to the screen.

If obtaining an original script is a problem, an interesting variation is to use a film adapted from a stage play and study an obligatory scene, that is, one so dramatically necessary that it cannot be missing from the film version. Good titles are:

Arthur Miller's Death of a Salesman

- Laslo Benedek's 1951 film version with Fredric March.

- Wim Wenders' 1987 TV version with Dustin Hoffman. It is interesting for its expressionist sets and because a theatrical flavor is retained.

Edward Albee's Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?

- Mike Nichols' 1966 film version.

Peter Schaffer's Equus

- Sidney Lumet's 1977 film version.

Tennessee Williams' A Streetcar Named Desire

- Elia Kazan's 1951 film version.

STRATEGY FOR STUDY

Study the Original

Try to select an unfamiliar work and read the whole script (or stage play). Choose a scene of four or five pages.

- Imagine the location and draw a floor plan (see Figure 5-3 for an example).

- Make your own shooting script adaptation, substituting action for dialogue wherever feasible and making use of your location environment. (See Figure 7-1 in Chapter 7 for standard screenplay layout.)

- Mark characters' movements on floor plan.

- Mark camera positions (A, B, C, etc., and indicate camera movements), and refer to these in your shooting script.

- Write a brief statement about (a) what major themes you think the entire script or play is dealing with, and (b) how your chosen scene functions in the whole.

First see the entire film without stopping. Then run your chosen scene two or three times, stopping and rerunning sections as you wish. Carry out the following:

- Make notes on film's choice of location (Imaginative? Metaphoric?).

- Make a floor plan and mark camera positions and movements of characters.

- Using a photocopy of the scene, pencil in annotations to show what dialogue has been cut, added, or altered.

- Note actions, both large and small, that add significantly to the impact of the scene. Ignore those specified in the original, as the object is to find what the film version has added to or substituted for the writer's version.

- Note camera usage as follows:

a. Any abnormal perspective (that is, when a nonstandard lens is used. A standard lens is one that reproduces the perspective of the human eye. Telescopic and wide-angle lenses compress or magnify perspective respectively)?

b. Any camera position above or below eye level?

c. Any camera movement (track, pan, tilt, zoom, crane)? Note what you think motivated the camera movement (character's movement, eyeline, Storyteller's revelation, etc.).

d. Note what the thematic focus of the film seems to be, and how your chosen scene functions in the film.

Comparison

Compare your scripting with the film's handling and describe the following:

- How did the film establish time and place?

- How effectively did the film compress the original and substitute behavior for dialogue?

- How, using camerawork and editing, is the audience drawn into identifying with one or more characters?

- Whose scene was it, and why?

- How were any rhythms (speech, movements, sound effects, music, etc.) used to pace out the scene, particularly to speed it up or slow it down?

- What were the major changes of interpretation in the film and in the chosen scene?

- Provide any further valuations of the film you think worth making (acting, characterization, use of music or sound effects, etc.).

Assess Your Performance

How well did you do? What aspects of filmmaking are you least aware of and need to develop? What did you accomplish?

PROJECT 5–4: LIGHTING ANALYSIS

Though directors do not have to understand techniques of lighting, they must be able to ask for particular lighting effects and discuss lighting using the terminology a DP understands.

Equipment Required: VCR as in previous projects. Turn down the color saturation of your monitor so that initially you see a black-and-white picture. Adjust the monitor's brightness and contrast controls so the greatest possible range of gray tones is visible between video white and video black. Unless you do this you simply won't see all that is present.

Objective: To analyze common lighting situations and understand what goes into creating a lighting mood

Study Materials: Same as in previous project (a film script and the finished film made from it on videotape), only this time it will be an advantage to search out particular lighting situations rather than sequences of special dramatic appeal. The same sequences may fulfill both purposes.

LIGHTING TERMINOLOGY

Here the task is to recognize different types and combinations of lighting situations and to apply standard terminology. Every aspect of lighting carries strong emotional associations that can be employed in drama to great effect. The technique and the terminology describing it are therefore powerful tools in the right hands. Here are some basic terms:

Types of Lighting Style

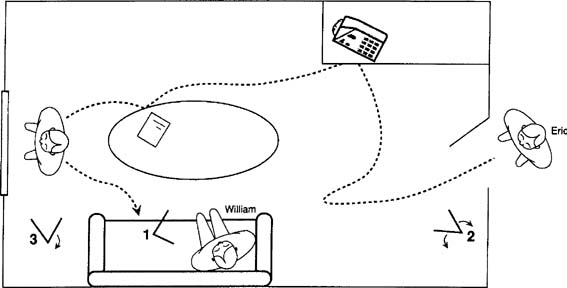

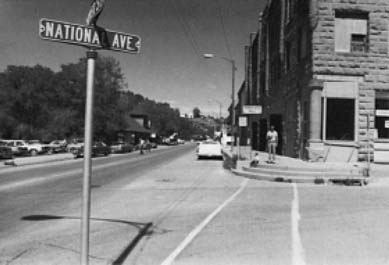

High-key picture: The shot looks bright overall with small areas of shadow. In Figure 5-4 the shot is exterior day, and the shadow of the lamppost in the foreground shows that there is indeed deep shadow in the picture. Where shadow is sharp, as it is here, the light source is called specular. A high-key picture can be virtually shadowless, so long as the frame is bright overall.

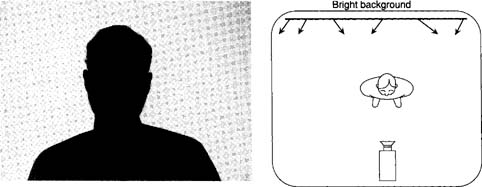

Low-key picture: The shot looks dark overall with few highlight areas. These are often interiors or night shots, but in Figure 5-5 we have a backlit day interior that ends up being low-key, that is, having a large area of the frame in deep shadow.

Graduated tonality: The shot has neither bright highlights nor deep shadows, but consists of an even, restricted range of midtones. This might be a flat-lit interior, like a supermarket, or a misty morning landscape as in Figure 5-6. In that example, an overcast sky diffuses the lighting source, and the disorganized light rays scatter into every possible shadow area so there are neither highlights nor shadow.

Contrast

High-contrast picture: The shot may be lit either high- or low-key, but there must be a big difference in illumination levels between highlight and shadow area, as in Figure 5-7, which has a soot-and-whitewash starkness. Both Figures 5-4 and 5-5 are also high-contrast images, although the area of shadow in each is drastically different.

High-key scene: hard or specular lighting, high-contrast. Notice compositional depth in this shot compared with the flatness of Figure 5-5.

FIGURE 5-5

Backlit, low-key scene: Subject is silhouetted against the flare of backlit smoke.

Low-contrast picture: The shot can either be high- or low-key, but with a shadow area illumination level near that of the highlight levels. Figure 5-6 is high-key, low-contrast.

Light Quality

Hard lighting: This is any specular light source creating hard-edged shadows, such as sun, studio spotlight, or candle flame. These are all called effectively small light sources because a small source gives hard-edged shadows. Figure 5-4 is lit by hard light (the sun), while the shadow under the chair in Figure 5-5 is so soft as to be hardly discernible.

Soft lighting: Any light source is soft when it creates soft-edged shadows or a shadowless image, as in Figure 5-6. Soft light sources are, for example, fluorescent tubes, sunlight reflecting off a matte-finish wall, light from overcast sky, or a studio soft light. Do not confuse soft lighting with lighting that is of low power. A candle is a low-power, hard-lighting source.

Names of Lighting Sources

Key light: This is not necessarily an artificial source, for it can be the sun. The key is the light that creates intended shadows in the shot, and these in turn reveal the angle and position of the supposed light source, often relatively hard or specular (shadow-producing) light. In Figure 5-4 the key light is sunlight coming from the rear left and above the camera. In Figure 5-5 it is streaming in toward the camera.

Fill light: This is the light used to raise illumination in shadow areas. For interiors it will probably be soft light thrown from the direction of the camera, because this avoids creating additional visible shadows. There are shadows, of course, but the subject hides them from the camera's view. Especially in interiors, fill light is often provided from matte white reflectors or through diffusion material such as heat-resistant fiberglass. Fill light can also be derived from bounce light, which is hard light bounced from walls or ceilings to soften it.

Backlight: This is light thrown upon a subject from behind—and often from above as well as behind, as in Figure 5-5. A favorite technique in portraiture is to put a rim of backlight around a subject's head and shoulders to separate them from the background. Rain, fog, dust, and smoke (as in this case of garage bar-becuing) all show up best when backlit.

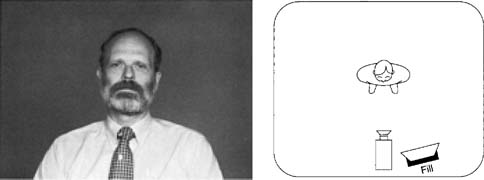

Practical: This is any light appearing in the frame as part of the scene; for example, table lamp, overhead fluorescent, or, as in Figure 5-8, the candles on a birthday cake. Practicals generally provide little or no real source of illumination, but here the candles light up the faces but not the background.

Figure 5-8 illustrates several lighting points. The girl in the middle is lit from below, a style called monster lighting, which is decidedly eerie for a birthday shot. The subject on the left, having no backlight or background lighting, disappears into the shadows, while the one on the right is outlined by set light or light falling on the set. The same light source shines on her hair as a backlight source and gives it highlights and texture.

Types of Lighting Setup

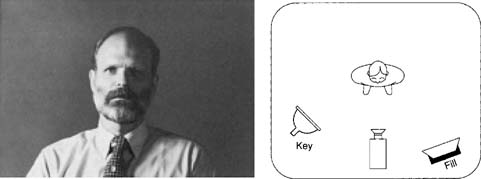

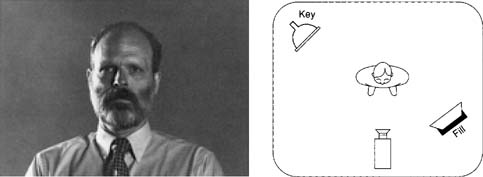

In this section the illustrations are of the same model lit in various ways. As a result, the effect and the mood in each portrait vary greatly. The diagrams show the positioning of the key and fill lights. A floor plan can show the angle of throw relative to the camera-to-subject axis, but not the height of light sources. These can be judged from the screen image by assessing the positioning of highlight and shadow patterns.

Frontally lit: The key light in Figure 5-9 is so close to the camera-to-subject axis that shadows are thrown behind the subject and out of the camera's view. Very slight shadows are visible in the folds of the subject's shirt, showing how the key was just to the right of camera. Notice how flat and lacking in dimen-sionality or tension this shot is compared with Figures 5-10 and 5-11.

Broad lit: In Figure 5-10 the key light is some way to the side, so a broad area of the subject's face and body is highlighted. Key light skimming the subject lengthens his face, revealing angles and undulations. There are areas of deep shadow, especially in the eye sockets, but their effect could be reduced by increasing the amount of soft fill light.

Narrow lit: The key light in Figure 5-11 is to the side of the subject and beyond him so that only a narrow portion of his face receives highlight. The majority of his face is in shadow. The shadowed portion of the face is lit by fill light, or we would see nothing. Measuring light reflected in the highlight area and comparing it with that reflected from the fill area gives the lighting ratio. Remember

FIGURE 5-10

Broad lighting illuminates a broad area of the face and shows the head as round and having angularities.

FIGURE 5-11

Narrow lighting illuminates only a narrow area of the face. More fill used here than in Figure 5-10. The effect is decidedly dramatic.

when taking measurements that fill light spills into highlight areas but not vice versa, so reliable readings can only be taken when all lights are on.

Silhouette: In Figure 5-12 the subject reflects no light at all and shows up only as an outline against raw light. This lighting is sometimes used in documentaries when the subject's identity is being withheld. Here it produces the ominous effect of someone unknown confronting us through a bright doorway.

Day for night: Shooting exteriors using daylight (day-for-day) presents few problems, but direct shooting at night or in moonlight is virtually impossible because neither film stocks nor video cameras approach the human eye's sensitivity. One solution is to shoot night-for-night by carefully modeling bluish artificial light to cast long, hard-edged shadows that simulate those cast by the light of the moon. Day-for-night shooting is easiest in black-and-white, because you can use early morning or late afternoon sunlight when shadows are long, under-expose by several stops, and use a red or yellow filter to turn blue skies black and increase all-round contrast. Day for night in color uses a similar lighting and exposure strategy, and a graduated filter to darken the sky, but seldom looks very convincing. A more effective color day-for-night effect results from using the so-called “magic hour,” a period of little more than 10–20 minutes just before there is too little light to shoot. In urban scenes, streetlights and car headlights are on, and the whole landscape is still visible under what is often a gorgeous reddish sky. Any dialogue scenes of more than a line or two in a single shot must be taken later in close-up with artificial lighting and backgrounds that match the long shots.

STRATEGY FOR STUDY

Locate two or three sequences with quite different lighting moods, and using the previously discussed definitions, classify them as follows:

After analyzing several sequences in black-and-white, see if you can spot further patterns by turning up the color. This often reveals how the DP and art director have employed the emotional associations of the location, costuming, and décor in the service of the script. Predominant hues and color saturation level (meaning whether a color is pure or desaturated with an admixture of white) have a great deal to do with a scene's effect on the viewer. For instance, David Lynch's Blue Velvet (1986) portrays its Lumberton in stark, bright toy-town colors as a surreal setting for sadistic sex and loneliness. Robert Altman's Gosford Park (2001) uses the low-key interiors and crowded sets of a Victorian country mansion as the setting for this convoluted family tale. The predominant tones are dark red and brown.

Two classically lit black-and-white films are Orson Welles' Citizen Kane (1941) with deep-focus cinematography by the revolutionary Gregg Toland, and Jean Cocteau's Beauty and the Beast (1946) whose lighted interiors Henri Alekan modeled after Dutch paintings. A much more recent black-and-white film with lighting by Alekan is Wim Wenders' poetic Wings of Desire (1987).