CHAPTER 13

GENRE, CONFLICT, AND DIALECTICS

MAKING THE VISIBLE SIGNIFICANT

Memorable cinema communicates an integrated point of view not just as the occasional garnish by subjective camera angle or interior monologue, but as a feeling of access to a fellow spirit's inward eye and outward vision. We're not talking about heroic and idealized characters enshrined by the star system, but rather the kind of cinema that makes you see unfinished business in your life or society.

How else can you go about reflecting such things on the screen? Robert Richardson defines the heart of the problem: “Literature often has the problem of making the significant somehow visible, while film often finds itself trying to make the visible significant” (Literature and Film, Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, 1973, Chapter 5, p. 68). Film's surfeit of realistic detail is inclined to deter the audience from looking any deeper than the surfaces rendered so minutely and attractively by the camera. This can lead to simplistic valuations. There are many subtle ways, of course, that film authorship can draw our attention to a film's subtext, but without using film language astutely, an underlying discourse can go completely unnoticed.

The fiction film, the documentary, and the short story have something in common. All are consumed at a sitting and so perhaps carry on the oral tradition, which at one time constituted (along with religion) the entirety of the ordinary person's education. Like the oral tale, these forms seem best suited to representing history that is personally felt and experienced rather than issues and ideas in abstraction. Any short, immediate form must entertain if it is to connect with the emotional and imaginative life of a mass audience. Like all entertainers, the filmmaker either understands the audience or goes hungry. Richardson argues convincingly that the vitality and optimism of the cinema, in contrast to other 20th-century art forms, is a result of its collaborative authorship and dependence on public response.

The cinema's strength and popularity lie with its power to make an audience see and feel from someone else's point of view. In the cinema we see through different eyes and experience visions other than our own. For significant sections of the world, recently divested of thousands of years of spiritual beliefs, this is a reminder of community and of something beyond self whose value cannot be underestimated. Just as importantly, the best cinema is relativistic, that is, it allows us to experience other related but opposing points of view. Used responsibly, this is an immensely civilizing force to offset the conformity imposed by merchandisers striving to convert us into a compliant admass.

OPTIONS

Anyone planning even the shortest film must make fundamental aesthetic choices at the outset. These are by no means completely free because all films depend on screen conventions. There are choices in screen language, but other choices are driven by the type of story. Storytelling has deep roots that precede film, printing, and even written history. Let's examine the notion of story as it reaches us from the screen.

At its best, the screen exercises our consciousness so successfully that a recently seen movie can afterward feel more like personal experience. Through the screen we enter an unfamiliar world or see the familiar in a new way. We share the intimate being of people who are braver, funnier, stronger, angrier, more beautiful, more vulnerable, or more beset with danger and tragedy than we are. Two hours of concentrating on a good movie is 2 hours during which we set aside the apparent unchangeability of our own lives, assume other identities, and live through a different reality. This world can be wonderfully dark and depressing, light and idealizing, or one that plumbs the unanswered questions of the present with wit and intelligence. We emerge from a good movie energized and refreshed in spirit.

This cathartic contact with the trials of the human spirit is a human need no less fundamental than eating, breathing, or making love. It is what helps us to live fully. In our daily lives an excess of emotional movement or a lack of it will send us to the arts looking for reflected light. Quite simply, art, of which the cinema is the newest form, nourishes us in spirit by engaging us in surrogate emotional experience and implying what patterns lie behind it. It helps us make sense of our past, deal with our present, and prepare us for what might await us in our future. It shows us that what seemed isolatingly personal is really inside the mainstream of human experience. Art allows us to pass into new realities, become other, and return to ourselves knowing more about the human family.

All art grows out of what went before it, even when the artist is deemed highly original. This means that you must choose an area in which to work, a language through which to speak to an audience, and perhaps some changes or variations you want to make to the genre. Pushing the envelope of form cannot be done unless you are intimate with conventions and why they exist.

GENRE AND POINT OF VIEW

Realism presents a story in documentary fashion as a set of interesting events in a world we accept as real or typical. Other genres project us into special worlds running under particular conditions. A slapstick or screwball comedy, a gothic romance, or a film noir each has emphases and limitations that are well understood by the audience. These arise from the area of life the genre deals with, but also from the heightened and selective perceptions of its protagonists. There is nothing inherently unreal, untruthful, or distorted about a genre once you accept that in life, people not only contend with reality but also create it through the force of their own perceptions. If “character is fate,” then a collection of characters can collusively create their own reality. History and the newspapers are full of examples.

We enjoy genres like historical romance, sci-fi, or buddy movies because we need to experience worlds beyond the suffocatingly rational one of everyday life. Sometimes we need to enter a “what if” world running under selectively altered circumstances. We buy into it by emotional choice, just as we learn the most vivid lessons from emotional immersion rather than from intellectual instruction. Watching Tolstoy's Anna Karenina, we expect to enter the adulterous heroine's sufferings, not simply be told she is immoral. We want to know how it feels to be a young woman married to a stuffy older man, to feel isolated and loveless, and then to be approached by a romantic admirer. What does it feel like to be tempted—and then viewed by society as the temptress?

When a movie is good, we imaginatively experience these conditions and come away expanded in mind and heart. To make this happen, the cinema must project us into a main character's emotional predicament, for our main and perhaps only desire is to inhabit the worlds of others. In a love triangle like Anna Karenina there is more than one emotional situation because separate and different perceptions are possible by each character—that is, Anna's, her husband's, and her lover, Vronsky's. With the husband, Karenin, we might view Anna's liaison as a betrayal; with Vronsky, as a romantic adventure that turns sour; and with Anna, feel night turn into brightest day, then change into a long, bloody sunset.

A story has dimensions beyond those understood by its protagonists. In Anna Karenina there is the overarching watchfulness of the storyteller, Tolstoy, and still others superimposed by anyone subsequently reinterpreting the novel. Altered perspectives often require no change in the interactions specified by the original novel. They simply impose a slant or filter drawn from a contemporary mood or conviction.

Finally, as discussed previously, the audience brings a POV to the piece. This is affected by national culture, as well as social, economic, or other contexts. A Chinese village audience does not interpret the film the same way as a San Francisco or Turin audience does. Stories, domestic or foreign, are consumed by a culture to find reflected aspects and meanings for itself, which is why a Shakespeare play can be set in recent times and still resonate loudly in modern India.

To control a genre, a director must know what the special conditions of that genre are, and how to create and handle points of view within the film

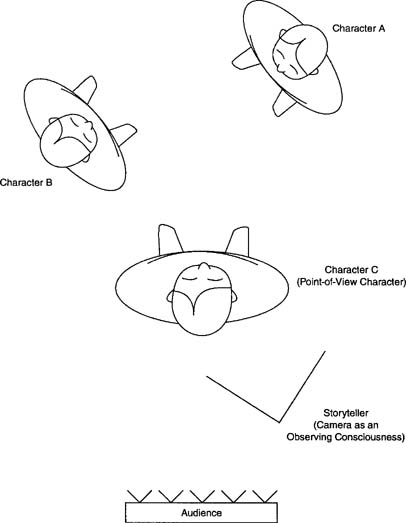

to build the subjectivity of a special world. The director must analyze a story or screenplay and know whose subjectivity is important at any given point (Figure 13–1).

GENRE AND DRAMATIC ARCHETYPES

In French, genre simply means kind, type, or sort, and in English the word is used to describe films that can be grouped together. James Monaco's How to Read a Film (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000) lists under genre:

| black film | gangster film | thriller |

| buddy film | horror film | war film |

| chase | melodrama | westerns |

| comedy (screwball) | musicals | youth |

| detective story | samurai | |

| film noir | science fiction |

For television it lists:

| action shows | docudrama | soap opera |

| cop shows | families | |

| comedy (sitcom) | professions shows |

Each category is archetypal because it contains characters, roles, or situations somewhat familiar to the audience. Each therefore promises to explore a known world running under familiar rules and limitations. The buddy film is usually about same-sex friendships, though it may contain works as diverse as Kramer's The Defiant Ones (1958), Hill's Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969), and Hughes' Planes, Trains and Automobiles (1988). Ridley Scott's Thelma and Louise (1991) is a female version.

The gangster film, the sci-fi film, and the screwball comedy all embody subjects and approaches that function dependably within preordained limits. Screen archetypes have their roots in a cultural history infinitely longer than that of the cinema. Audiences have always craved alternatives to realism, so it is hardly surprising that horror and fantasy have been staples throughout cinema's short history. They are cinema's variation on folk tales and folk drama, forms through which humankind still indulges its appetite for demons, ogres, wizards, and phantom carriages. Under the guise of futurism, Schaffner's Planet of the Apes (1968) and Lucas' Star Wars (1977) are really old-fashioned morality plays whose settings obscure, but do not efface, their ancient origins. Even the revolutionary Godard in A Woman Is a Woman (1961) explores well-worn ground in his young couple setting up house together, but it's done with characteristic humor and playfulness (Figure 13–2).

Though fiction cinema allows you to vicariously experience most imaginable fates, there has been a conspicuous silence on nuclear attack and on the Holocaust, at least until Spielberg's Schindler's List (1994). Even so, the film focuses on one of the few uplifting stories to emerge from that period of brutality and shame. True horror, it would seem, is nothing we really care to contemplate.

Comedy in its different forms offers worlds with constants to which we can turn with anticipation. Chaplin, Keaton, Mae West, W.C. Fields, Red Skelton, Laurel and Hardy, as well as Tati, Lucille Ball, Woody Allen, John Cleese, and Steve Martin all play types of characters that are recognizable from film to film. Each new situation and dilemma pressures a familiar and unchanging personality with a new set of comic stresses.

Comedy's underlying purpose is said to be making audiences laugh at their own deepest anxieties and trauma. Harold Lloyd hanging from Manhattan skyscrapers and Chaplin working frantically to keep up with a production line or playing the dictator are obvious examples. But recent sex comedies in which women take over male preserves, homosexual couples take on parenthood, or sitcoms involving men taking over women's roles and identity all confirm how comedy functions as a safety valve for anxieties about social change.

That audiences should want to vicariously investigate anxiety, fear, or deprivation is easier to understand than other kinds of experimenting. The sexploitation film with its portrayal of women as willing objects of misogynistic violence and the “slasher” film portraying sadistic brutality prompt disturbing questions about manipulation and responsibility for the darker side of the (mostly male) human imagination. Perhaps secular, middle-class living has so effectively banished fear and uncertainty that we recreate the primitive and supernatural to allay that worst of all bourgeois ills: terminal boredom.

Brecht's question remains. Is art a mirror to society or a hammer working on it? Does art reflect what is, or does it create it? The answers are likely to vary with the makers of the artwork, and with history and even the age of those involved. What we can say with confidence is that in every period and in every part of the world, art has supplied a surrogate experience to exercise hearts and minds. Sometimes actuality is dramatic and mysterious enough on its own (as during war or an unimaginable event like the World Trade Center destruction); at other times we gravitate toward works presenting elaborate metaphors for our condition, particularly as we approach taboos.

But how does the poor filmmaker, surrounded by the paraphernalia of scripts, budgets, and technical support, know when to abandon the kitchen sink realism so generic to photography? What we need are guidelines to put individual perception into a manageable frame. I wish there were a magic formula, but instead we must talk about dialectic worlds animated by the creative tensions of opposition.

DUALITY AND CONFLICT

Have you ever received one of those photocopied family newsletters around Christmas time?

The Russell News for the Year

David received his promotion to area manager but now has a longer drive to work. Betty has completely redecorated the dining room (with an avocado theme!) after successfully completing her interior decorator course at Mallory School of the Arts. Terry spent the summer camping and canoeing and thoroughly enjoyed being a camp counselor. In the fall he learned he had a place at Hillshire University to study molecular biology. In spite of what the doctor said, Joanne has successfully adapted to contact lenses. …

What makes this insufferable is that the writer insists on presenting life as a series of happy, logical steps. In the Russell photo album, everyone faces the camera wearing a smile. There will be nothing candid, spontaneous, or disturbing. The newsletter events are not untrue, but the selection method renders them lifeless, especially if you happen to know that David's drinking problem is getting worse.

By avoiding all hint of conflict, the account is rendered insipid. It totally suppresses the dissent, doubt, and eccentricity that makes every family turbulent. Family life is like a pond; calm on the surface but containing all the forces of warring nature below the surface. So, too, is an individual. A person's life does not move forward in linear steps like an adding machine. Instead it moves like a flying insect in a zigzag pattern formed by conflicting needs and random conditions. Joanne Russell needs her mother's emotional support, but cannot bear the way she criticizes her. Terry Russell wants to go to college, but dreads leaving friends and home behind him. Each has conflicting feelings over these issues, and each feels contradictory impulses in dealing with them.

The individual psyche is like a raft on the ocean moving irregularly under the conflicting wills of those (the passions) rowing on all four sides. Most row peaceably together in one direction, but a few dissidents struggle to send the raft in their own direction. Imagine now several such rafts in conflict with each other, and you have a family.

MICROCOSM AND MACROCOSM

Because drama reproduces on a large scale the warring elements found in an individual, the screenwriter could make drama from something like an exploded diagram of a single human being. By selecting aspects of the complex subject's personality (usually modeled to his or her own) and expanding them into separate characters, one can be set in conflict with the others. This takes what would normally be an internal and mental struggle and transforms it into outwardly visible action—so necessary for the screen.

Conversely, when a diffuse, complex situation needs to be presented coherently, it can be miniaturized by reversing the process to make the macrocosm a microcosm. Oliver Stone's Wall Street (1988) concentrates and simplifies trends in the stockbrokering industry into a parable. A young stockbroker is seduced into illegal practices by the charisma of a powerful and amoral mentor. His counterbalancing influence is his pragmatic, working-class father. Interestingly, a similar configuration of influences vie for the hero's soul in Stone's Platoon (1987). In each case, a complex and otherwise confusing situation is simplified and made accessible because characters are created to represent moral archetypes. As the Everyman central character makes choices, we see him tempered in the flame of experience.

If you make a character into a torchbearer for a human quality, take care that he or she doesn't become monolithic and flat. It is not enough for one quality to predominate; each character must be complex and facing some vital conflicts of his or her own.

HOW OUTLOOK AFFECTS VISION: DETERMINISM OR FREE WILL?

When a piece is character-driven, the storyteller's vision of the particular world will depend on the POV character. When the piece is plot-driven, the storyteller's vision will hinge more on settings, situations, and the idiosyncrasies of the plot. Temperamental and cultural factors also influence the filmmaker's choices. The political historian or social scientist, for instance, may see a naval battle as the interplay of inevitable forces, with victory or defeat being the result of the technology used and the different leaders' strengths and weaknesses. This is a deterministic view of human behavior that might produce a genre film. It is relatively detached and objective and will express itself similarly whether it works through comedy, mystery, or psychological thriller.

Other dramatists, concerned with the individuality of human experience, treat a battle differently—going below decks, looking into faces and hearts, and seeking out the conflicts within each ship and within each sailor, the great and the humble. Such a film might place us in the heat of battle to show not the constants in human history or the eternal repetition of human error, but the human potential inherent in moral choice. This kind of film is likely to show a more individual vision and a less predictable world because it wants to raise questions about character and potential rather than demonstrate the repetition of historical patterns.

Whether you show a deterministic world or one where individuals influence their destinies will be a matter of your temperament and the story you want to tell. It is also, as I say often, a matter of what marks life has made on you and therefore what stories you need to tell. Luckily there are many limitations on choice.

DRAMA, PROPAGANDA, AND DIALECTICS

Drama and propaganda handle duality differently: Drama sees the live organism of the sea battle while the propagandist, knowing before he starts where the truth lies, drives his audience single-mindedly through a token opposition to arrive at a prescribed victory. His drama is not a process of exploration but of jostling the spectator into accepting a predetermined outcome, much as salesmen's stories are directed at selling their merchandise. Television or cinema with a message arouses our defenses because we are being sold cheap goods under the guise of entertainment, and instinctively we resent it.

The dramatist, valuing the complexity, integrity, and organic quality of struggle and decision, treats audiences more respectfully. Truly dramatic writing evolves from exploring the author's fascination with particular ambiguities. To some degree it is always a journey toward an unknown destination. The absence of this quality makes most well-intentioned educational and corporate products stultifyingly boring. The makers have either forgotten or are incapable of recreating the sense of discovery. The viewer is treated like a jug, a passive receptacle to be filled with information, and not an active partner in discovery. The educator with a closed mind wants to condition us, not invoke our free-ranging intelligence. This is why art under totalitarianism comes from the dissidents, never the establishment.

We face a range of artificial oppositions between which any film will ambiguously be suspended. Here are those mentioned so far, as well as a few extra.

| Either | Or |

| Auteur (personal, authorial stamp) | Genre (film archetype) |

| Subjective (character's) POV | Objective (storyteller's) POV |

| Non-realistic, stylized | Realistic |

| Duality requires audience judgment | Conflicts are generic and not analyzed |

| Conflicts are interpersonal | Conflicts are large-scale and societal |

| Conflicts are divergent and unresolved | Conflicts are convergent and resolved |

| Outcome uncertain | Outcome satisfyingly predictable but not reached without struggle |

Notice that these columns are neither prescriptions for good and bad films, nor do many films fall into predominantly one column or the other. They are simply alternates. How do you decide which oppositions to invoke in your particular piece of storytelling?

At the point of deciding what story and what kind of world the protagonists of the story inhabit, it is unimportant. This will emerge later. What matters is to keep in mind that everything or everybody interesting always has contradictions at the center, and that every story must be routed through the intelligence experiencing the story as it unfolds. We have personified this intelligence as the Concerned Observer.

BUILDING A WORLD AROUND THE CONCERNED OBSERVER

You will recall that, relieved of corporeal substance, the Observer is invisible and weightless like a spirit and sees all the significant aspects of the characters. Feeling for them, the Observer sometimes leaves the periphery to fly into the center of things, but remains mobile and involved and always in search of greater significance and larger patterns of meaning.

Developing empathy with the characters and knowledge of them, the Observer passes through a series of experiences that invoke identification with the characters, strain his or her powers of understanding, and stress his or her emotions. Following are some invented examples for discussion.

SURVIVAL FILM

You have set your film in the rubble after World War III. You have chosen to use realism to allow the audience no escape and to make the audience identify with a family that has survived through a freak occurrence. There are some interpersonal conflicts (over what is the best direction to follow in search of water), but most of the struggle is between the family and the hostile environment. The trials faced are for survival and involve bravery and ingenuity rather than self-knowledge and human judgment. You want your audience to be affected by the bleakness of the environment, the tragedy of humankind having wiped itself out, and the futility of your lone family's efforts. Their hope is to meet others. Their fear is not finding enough food or shelter to survive an endless winter. You want to show the resourcefulness and compassion of a family unit under extreme duress.

LOTTERY WINNER FILM

An elderly widower goes from genteel poverty to stupendous wealth by winning the lottery. He decides to indulge his two best friends with everything they have ever wanted. Each, according to his minor flaws, becomes distorted by the bounty in a major way, and each finds that getting what you want brings more trouble than it is worth. In the end the three are forced to separate and begin new lives apart.

Here you can show three different characters in three different phases of reality, all very subjective, and you can occasionally drop back to a more objective storyteller's mode. The conflicts each character suffers are mostly internal—over suddenly having to opt for what makes them happy. There is much doubt and self-examination and perhaps conflict among the three friends as they find themselves in deep waters. The lottery winner feels responsible, and often we will see things through his eyes. The world, which is first a desert, becomes a cornucopia of delights; then it becomes complicated and troublesome. The lottery winner finds he likes his friends less and less until they all agree to give up the life they have taken on. The price of affluence is isolation.

Your intention is to show how security and a sense of self-worth comes from facing problems, and that people fall on their faces when there is nothing left to push against. This is a subtle subject, for it shows how fragile people become when accommodating an excess of good fortune.

Neither of the above are unusual subjects, yet the world you show and the roles in which you place the audience enable you to create a progression of experiences that explore the human condition. The same would be true for any form of film you choose, provided you decide not only upon the characters' careers, but also the role of the subjective, watching audience—a role that normally emerges by default rather than by conscious design.

OBSERVER INTO STORYTELLER

While the literary storyteller always tells a story that has already happened, the film storyteller summons us into a story that is happening here and now. In this respect, screen language is alien to human experience, for we never experience an account except through someone else's persona and in retrospect. Film violates this in two ways: One, we see through other eyes yet seem to see directly; two, we see in the present, not the past tense. This is clear from the example in a previous chapter of seeing someone's documentary coverage of his class reunion party. We experience the party happening not then, but here and now, and we have to remind ourselves that what we see is not objective truth but something filtered through a particular temperament.

Audiences and filmmakers resolve this psychic non sequitur by disregarding the storyteller—the subjective filter through which the world is seen in a certain way. Though you may not like every distinguished cinematic author such as Hitchcock, Godard, Resnais, Bergman, Fellini, Antonioni, Altman, Almodóvar, and Kiarastama, you never doubt whose hands you are in when watching one of their films. But much work for the cinema, and virtually all fiction made for television, lacks any individuality of vision whatsoever. As Mamet says, such movies are made “as a supposed record of what real people really did.” A film of this kind is a faceless newsreel documenting the story and characters and at best does a good job of being a Concerned Observer. Mamet's knowledge does not save him from falling into the same trap when he directs, so understanding the problem is far from being the solution. I think the answer lies in three areas:

- Create a definite Storyteller: A director must make the film's Storyteller have the subjectivity of a strong and interestingly biased personality, as is common to all effective storytelling voices. To obtain it for the film, the director must “play” the part while planning the film and directing it. That means imaginatively getting inside the storytelling sensibility like an actor. Any David Lynch film has a powerful sense of Lynch's storytelling presence. When such a subjective vision is there from the beginning all the way through shooting, a good editor will recognize it with delight and work to enhance it. Editors are usually trying to create the storytelling voice because it is absent.

- Take control: The director must psychically control the filmmaking process, not be controlled by it. This is a matter of having a strongly realized design for everything and having the confidence, clarity, and obstinacy to get this vision realized during the production process. The more professional the crew and actors feel they are, the more likely is the tail to wag the dog when the director fails to impose the necessary POV.

- Aim to go somewhere: With a destination in mind, you'll go where you aim. If you only want your film to look professional, you will eventually do so—but facelessly. Make your priority a good story seen in a specially discovered way, and you will be readily forgiven any lack of professionalism.