CHAPTER 18

CASTING

WHY CASTING MATTERS

Good casting contributes massively to the success of any film. Beginning directors often do it poorly by settling for the first person who seems right or who is reliable.

The object of auditioning is to find out as much as you can about the physical, psychological, and emotional make-up of each potential cast member so you can commit yourself confidently to the best choice. Doing this means initially putting many actors through a brief procedure to reveal their character and to indicate how each handles representative situations. Later there will be semifinal and final rounds of auditioning. The first aim is to identify broad characteristics:

- Physical self (features, body language, movements, voice)

- Innate character (confidence, outlook, reflexes, rhythm, energy, sociability, imprint made by life)

- Type of intelligence (sensitivity to others, perceptiveness of environment, degree of self-exploration, and cultivation of tastes)

- Grasp of acting (experience, concepts of the actor's role in drama, craft knowledge)

- Directability (interaction with others, flexibility, defenses, self-image)

- Commitment (work habits, motivation to act, reliability)

THE DANGERS IN IDEALS

There are two ways to approach casting.

- Can this actor play the father in my script? Naturally you wonder whether this particular man is right for the character of the father in your script. There is, however, a hidden bias in this attitude. The actor is being held up to an ideal of the character, as though the character were already formed and the actor either right or wrong. This puts emphasis on a premeditated image of the character and makes you view the actor through a cookie cutter. By this measurement the actor will always fail. Casting a film from a mental master plan is like marriage for the man who knows what Ms. Right must be before he has met her.

- What kind of father would this actor give my film? By this approach you acknowledge that the role is capable of many possible character shadings. Casting becomes development rather than fulfillment. Very importantly, you are already treating the actor's physical and mental being as an active collaborator in the process of making drama.

THE CASTING PROCESS

Casting is a predictable process. It involves circulating character descriptions and finding actors to fill each part and to bring both tangible and intangible assets to what is in the blueprint. This is always an anxious time, but it's important to see what kind of character a person will produce because of who and what they inherently are. You want to ensure that you can work with cast members and that they are enthusiastic about the character they will play.

DEVELOPING CHARACTER DESCRIPTIONS

Before you can search for possible actors, make basic character descriptions to post in appropriate places (newspapers, theater, or acting school billboards) or to give over the phone. A typical list might look like this:

Ken, 15, tall and thin, nervous, curious, intelligent, overcritical, obsessed with science fiction

George, late 20s, medium height, medical equipment salesman, lives carefully and calls his parents each Friday; husband of Kathy

Kathy, early 30s, but has successfully lied about her age; small-town beauty queen gone to seed after a steamy divorce; met George through a dating service

Ted, 60s, bus inspector, patriot, grower of prize chrysanthemums, disapproving father of George

Eddie, 40s, washing machine repairman, part-time conjuror and clown at children's parties; too self-involved to be married, likes to spread home-spun philosophy

Angela, 70s, cheerful, resourceful, has a veneer of respectability that breaks down raucously after a couple of drinks; in early life made a fortune in something illicit and determined to live forever

Thumbnail sketches compress a lot into a few words and allow the reader to infer possible physical appearances. They also present an attractive challenge to people who would like to fill these roles.

ATTRACTING APPLICANTS

In every aspect of filmmaking, supply yourself with an abundance of choice. Apply this principle particularly to casting because the human presence on the screen is mostly how you command your audience's attention. Though the audience might be inexpert in screen technique, they are an absolute authority on the validity of the human presence. Here you can easily be more naive than your audience, especially if you cast a friend or loved one in a main part. I once edited a film where the director simply couldn't see how inadequate his wife was in the main part and fiercely resisted being told.

Casting among beginners is usually the least rigorous part of the whole process. Feeling uncomfortable with the power to choose among fellow aspirants, the embarrassed newcomer settles too early and too easily for actors who look right. Age and appearance matter, but this is only the beginning. All 40-year-old men are not alike, and to presume you can take the right face and make its owner into the script's sentimental, spendthrift father is asking for trouble.

Inadequate casting usually arises from a lack of:

- Confidence in your right to search far and wide

- Knowledge about how to discover actors' underlying potential

- Self-knowledge about who you can work with and who you cannot

Learning how to audition helps to remove the crippling sense of inadequacy and embarrassment about making human choices. Using a video camera delays decision making until you can, if you wish, enlist the opinions of key production members.

PASSIVE SEARCH FOR ACTORS

If you live in a city, you can spread a large net simply by putting an advertisement in the appropriate papers. Be warned that large nets bring in some very odd fish and sometimes bring in nothing at all.

ACTIVE SEARCH FOR ACTORS

If there is a fair amount of theater in your area, there is probably a monthly auditions broadsheet, Web site, or other professional contact method. In it, describe the project and give the number, sex, and age of the characters in a few words and a phone number to contact.

Apart from the oldest and youngest in the sample cast described earlier, the rest are drawn from an age bracket normally immersed in daily responsibilities. Three of the adults are blue-collar parts, a social class least likely to have done any acting and most liable to feel inadequate and self-conscious. These are generalizations whose only function is to help focus the search and indicate what kind of inventiveness is needed to locate the exceptions with the necessary qualities and spare time.

Anyone who lacks a liberal budget must be resourceful in finding likely people to try out. Wherever possible, save time and frustration by actively seeking out likely participants. First contact key people in theater groups. Locate the casting director and ask if you can pay a brief visit. Whoever handles casting will have a wealth of information about local talent, but be careful to clarify that you will take care not to poach in their preserves. The next most knowledgeable people are the producers (who direct in the theater) and other committed theater workers. Knowledgeable members will often respond enthusiastically with names you can invite to try out. When a theater group is successful enough to use only professional (union) actors, the response is likely to be cautious or even downright unfriendly. Theaters don't like their best cast members seduced away by screen parts and may want to avoid prejudicing their relationship with the actors' union. Don't be surprised if you get a tight-lipped referral to the actors' union.

If your budget is rock bottom, you will have to work hard. Actors well suited to specific parts can always be found, but it takes ingenuity and diligence. Never forget that if you have a good script, your film's credibility comes not from your film technique, but from how believable you can make the human presence on the screen. Good film technique simply provides a seamless storytelling medium. The better it is, the more the audience dwells on that all-important human presence.

For the character of 15-year-old Ken, I would track down teachers producing drama in local schools and ask them to suggest boys able to play that character well. The teacher can ask the child, or the child's parents, to get in touch. This allays the nightmare that their child is being stalked by a coven of hollow-eyed pornographers.

Elderly people are more of a problem. Because most cultures sideline the old, many become physically and mentally inactive. Your first task in casting Ted and Angela will be to locate older people who keep mentally and physically active. You may be lucky and find a senior citizen's theater group to draw upon or you may have to track down unusual individuals.

For Ted, I would look among older blue-collar men who have taken an active and extroverted role in life, perhaps in local politics, union organizing, entertainment, or salesmanship. All these occupations require some flair for interaction with other people and a relish for the fray.

Angela is a hard person to cast, but try looking among retired actresses or vocal women's group members such as citizen's and neighborhood pressure groups—anywhere you could expect to find an elderly woman secure in her life's accomplishments and adventurous enough to play a boozy, earthy woman with a past.

While you cast, remind yourself periodically that hidden among the gray armies of the unremarkable there always exist a few individuals in any age group whose lives are being lived with wit, intelligence, and individuality. Such people rise to prominence in the often-unlikely worlds to which exigency or eccentricity has taken them. Angela, for instance, might be the president of the Standard Poodle Fanciers Club, and Ted might be discovered through attending an amateur comedian contest or a poetry slam.

Werner Herzog's actors, for instance, include non-professionals drawn from around him. The central figure in The Mystery of Kasper Hauser (1974) and Stroszek (1977) is played by the endearing Bruno S—, a street singer and Berlin transport manager whose surname has remained undisclosed to protect his job. Robert Bresson, who refused to cast anyone trained to act, used lawyers in The Trial of Joan of Arc (1962) to play Joan's inquisitors. A lifetime spent defining details gave them just the right punctiliousness in their cross-examining. In his Notes on the Cinematographer (Los Angeles: Green Integer, 1997). Bresson gives a compelling rationale, akin to a documentary-making attitude, for using “models” (his word for players) who have never performed before.

SETTING UP THE FIRST AUDITION

FIELDING PHONE APPLICANTS

Many people who present themselves as actors are minimally experienced. The world is full of dreamers looking for that path to stardom; these should be avoided except for very brief, undemanding parts. A rigorous audition helps weed out the half-hearted. Add the obviously unskilled to a waiting list so you can audition those claiming experience first. As each person calls, you must be ready to politely abort the procedure at any stage. Try informing potential cast in this order:

- The project and your experience. Be direct and realistic. If you are a student group, say so. Use this as leverage to find out the person's experience in acting. If they claim film experience, ask their impressions of the process.

- Time commitment and any remuneration offered. Be truthful about the time rehearsal and shooting will take, and emphasize that filming is slow at the best of times. Any cool responses or undue negotiating are a danger bell indicating the applicant's high ego or low level of interest.

- The role in which the actor is interested. Question the actor to find out whether his or her characteristics are appropriate, and be ready to suggest an alternate part if the person sounds interesting.

- An audition slot if the person sounds appropriate.

- What the audition will demand. A first call might ask actors to perform two contrasting 3-minute monologues of their own choosing and take part in a cold reading.

CONDUCTING THE FIRST AUDITION

This session aims to net as many people as practical so you can later have callbacks for those deemed suitable. Many respondents, in spite of what they said on the phone, will be devoid of everything you require or quite unrealistic about their abilities and commitment. In this winnowing operation, expect much chaff for very little wheat.

GATHERING INFORMATION

Schedule people into slots so that they arrive at, say, 10-minute intervals and can be individually received by someone who can answer questions. Have actors wait in a separate area from the audition space, and give each a form to complete, so later you have on file the following information:

- Name and address

- Home and work phone numbers

- Acting experience and any references

- Role for which actor is trying out

- Special interests and skills

The last is purely to get a sense of what attributes the actor may have that indicate special energy and initiative. You might also have a section asking actors to write a few lines on what attracts them to acting. This can reveal values and how serious and realistic the person is.

A good plan is to have trusted assistants in the holding area who can chat informally with incoming actors. This helps calm actors' fears and lets your assistants form impressions of how punctual and organized the actors seem and what their personalities are like. These can be most valuable later.

STARTING THE AUDITION

The actor can now be shown into the audition space where he or she will perform. Videotape the performances so you can review your choices later and make comparisons, especially when you see a lot of actors for one part.

Most people are trying to cover up how nervous and apprehensive they are at auditions, but this is not necessarily negative because it shows they attach importance to being accepted. The presence of a camera increases the pressure.

MONOLOGUES

It is good to see two brief monologues of the actor's choice and that show very different characters. These can tell you:

- Whether an actor habitually acts with the face alone or with the whole body

- What kind of physical presence, rhythm, and energy level he or she has

- What his or her voice is like (a good voice is a tremendous asset)

- What kind of emotional range he or she spontaneously produces

- What the actor thinks is appropriate for him- or herself and for your piece

Whether their choice of material is well or badly performed and whether you can “see” the character the actor is playing are very important. The actor's choice and handling of material also indicate what they think they do best. The choice may reflect intelligent research based on what the actor has found out about your production, or it may indicate an enduring self-image. A man trying out for a brash salesman who chooses the monologue of an endearing wimp has probably already cast himself in life as a loser whose best hope is to be funny. This will hardly do for, say, the part of someone vengeful. Here you may sense a quality of acquiescence that makes the actor psychologically and emotionally unsuitable for this part, though perhaps interesting for another.

COLD READING

For this you will need several copies of several different scenes. Depending upon whom is in your waiting room, you might want to try combining two men, two women, a man and a woman, an old person with someone young, and so on. It is a good idea not to use scenes from your film, but instead to find something from theatrical repertory that is analogous in mood and characters. You don't want whomever you choose to become fixed by early impressions of your script.

Your assistant can decide, based on whom is waiting, which piece to read next and give each actor a copy of the scene in advance.

In the cold reading you will:

- See actors trying to give life to a character just encountered and having to think on their feet

- See the same scene with more than one set of actors, and thus what each brings to the part

- Have the opportunity to compare what quickness, intelligence, and creativity are evoked by the bare words on the page

- Hear how each actor uses his or her voice

- See how some will use their bodies and inject movement

- Find out who asks questions about their character or about the piece from which the scene is drawn

Performances and behavior will affect you differently and often in ways that pose interesting questions. In a reading with two characters of the same sex, you can switch the actors and ask them to read again to see if the actors can produce appropriate and different qualities at short notice.

After actors have auditioned, always:

- Thank them

- Give a date by which to expect news of the outcome

- Make a note of something positive about their performance to help you be supportive of those you have to reject

DECISIONS AFTER FIRST ROUND OF AUDITIONS

If you have promising applicants, run the tapes of their contributions and brainstorm with your project coworkers. Discussing each actor's strengths and weaknesses usually reveals further dimensions of the candidates, not to mention insights into your crew members and their values.

Now comes the agonizing part. Call everyone who auditioned and tell them whether they were selected for callback auditions. Telling the bad news to those not selected is hard on both parties; mitigate the disappointment by saying something appreciative and positive about the person's performance. With the people you want to see again, set a callback date for further auditioning.

DANGERS OF TYPECASTING

Be careful when casting characters who have prominently negative traits. It can be disastrous during shooting if an actor slowly becomes aware that he was cast for his own negative qualities.

To varying degrees, all actors go through difficulties playing negative characteristics because of the lurking fear that these characteristics are really within their own make-up. The less secure the individual is, the more likely such self-doubts will become acute. A sure sign of this insecurity is when an actor makes a personal issue of his or her character's qualities and argues to upgrade them.

To protect yourself, ask any actors you are considering to outline their ideas about their character's negative traits. Their underlying attitudes may influence your choice. Villains are easy to play, but playing a stupid or nasty character may either be viewed as an interesting challenge or as a personal sacrifice by the actor. There are no small parts, said Stanislavski, only small actors.

LONG- OR SHORT-TERM CHOICES

It can be tempting to cast the person who is ahead of the pack because he or she gave something specially attractive at the audition. This actor may be brilliant or may later emerge as glib and inflexible, developing less than a partner whose audition was less accomplished. Caution dictates that you investigate not only what an actor wants to do, but also how well they handle the unfamiliar and how willing and interested they are to push beyond present boundaries. All actors of any experience are fervently committed in principle, but in practice may reveal something different. Acting involves the whole person, not just ideas, and you may find that a genially accomplished personality coming under the threat of the unexpected suddenly manifests bizarre forms of self-defense and resistance (see Chapter 20: Actors' Problems).

THE DEMANDING PART OF THE CHARACTER WHO DEVELOPS

Many parts require little in adaptability to direction. To cast a surly gas station attendant for one short scene requires little growth potential, whereas the part of a young wife who discovers her husband is dominated by his mother will call for extended and subtle powers of development. This character must go through a spectrum of emotions during which she changes and experiences deep feelings, so the director must find an actor with the openness and emotional reach to undertake a grueling rehearsal and performance process.

FIRST CALLBACK

When you are ready to call back the most promising actors who auditioned, you will need to prepare some additional testing procedures.

A READING FROM YOUR SCRIPT

Give some background to the scene, which should be demanding but only a few minutes in duration.

- Ask each actor to play the character in a specified way. After the readings, give critical feedback and directions to further develop the scene.

- Have them play the scene again and look for how the actors build on their initial performances, holding on to what you praised but altering the specified areas.

- For a further run-through, give each actor a different mood or characteristic to see what he or she produces when given a radically different premise.

IMPROVISATION

Give two actors brief outlines of characters in the script and outline one of the script's situations that involve them. Then:

- Ask your players to improvise their own scene upon the situation in the (unseen) script. The goal is not to see how close they get to the scripted original, but how they handle themselves when much of the creation is spontaneous.

- After they have done a version, give them feedback about aspects you see developing in their version, and ask for a further version, specifying some change in behavior and mood. Now you will be able to see not only what they can produce from themselves but how well they incorporate direction.

SECOND CALLBACK

INTERVIEW

By now you have formed ideas about each individual, which you want to confirm and amplify. Give your best candidates the script to read, but tell them not to learn any lines, because this will fix their performance at an embryonic stage.

After they have read the script, spend time informally and alone with each, encouraging him or her to ask questions and to talk about both the script and himself or herself. Look for realism, sincerity, and a genuine interest in drama. It is a good sign if an actor is sincerely excited because the script explores some issue that is genuinely central to his or her own life. It is also very important that the actors feel they have something to learn from working with you and your project.

Be wary of those who flatter or name-drop, who seem content with superficial readings, are inflexibly opinionated, or leave you feeling that they are stooping to do you a good turn. Avoid like the plague anyone who seems to be looking over your shoulder for something better.

MIX AND MATCH ACTORS

When you have multiple contenders for a lead part, try them out in different permutations so you can assess the personal chemistry each has with the others. In part, this is to see what they will communicate to an audience. I once had to cast a short film about a man in his 30s who becomes involved with a rebellious teenage girl. We rejected a more accomplished actor because there was something indefinable in his manner that made the relationship seem sinister. Another actor paired with the same actress changed the balance to give the girl the upper hand, as the story demanded.

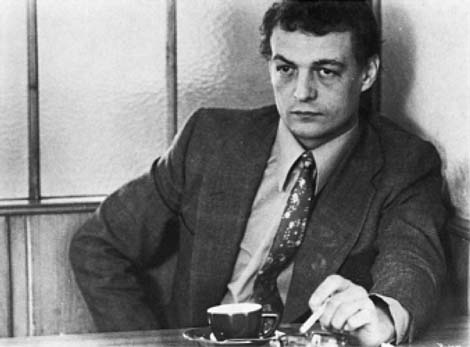

You also mix and match in search of the most interesting chemistry between the actors themselves. Sometimes two actors simply don't communicate well. Actors cast to play lovers must be tried out extensively with each other. There may be temperamental or other differences that render them unattractive to each other, but whatever the cause, the result will be a wariness and stiffness in their playing that could utterly disable your film. You always want to cast players who are responsive and interested in each other. Even when this is accomplished, you may still encounter problems. In Alain Tanner's The Middle of the World (1974), the male lead usually produced his best work in an early take while the woman playing opposite him slowly worked to her peak over a number of takes, sometimes leading to frustration all round (Figure 18-1).

FIGURE 18-1

Actors have different development rates. Philippe Leotard in Tanner's The Middle of the World (1974, courtesy New Yorker Films).

FINAL CHOICES

REVIEW YOUR IMPRESSIONS

Before making a final choice, review your impression of each actor's:

- Physical and temperamental suitability

- Impact

- Imprint on the part in relation to the other actors

- Rhythms of speech and movement

- Quickness of mind and directability

- Ability at mimicry, especially if he or she is to maintain a regional or foreign accent

- Voice quality (extremely important!)

- Capacity to hold on to both new and old instructions

- Ability to carry out his or her character's development, whether it is quick and intuitive or slower and more graduated

- Commitment to the project

- Long-term commitment to acting as a discipline

- Patience with filming's slow and disjunctive progress

- Ability to enter and re-enter an emotional condition over several takes and camera angles

- Compatibility with the other actors

- Compatibility with you, the director

CAMERA TEST

To confirm that you are making the right choices, shoot a short scene on videotape with the principal actors. Even then you will probably remain somewhat uncertain and feel you have to make difficult decisions.

If you have an overwhelming urge to cast someone that your intuition says is risky, you should tactfully but directly communicate your reservations. You might, for instance, feel uncertain of the actor's commitment or feel that the actor has a resistance to authority figures and will have problems being directed. Confrontation at this early point shows you how the actor handles uncomfortable criticism and paves the way should that perception later become an issue or, God forbid, should replacement become a necessity. An actor who seems arrogant and egocentric will sometimes gratefully admit, when faced with a frank reaction to his characteristics, that he has an unfortunate way of masking uncertainty.

More than anything, people in all walks of life crave recognition. If the director is able to comment on the potential and on any deficiencies that mask it, the serious actor will respond with warmth and loyalty. Sharing and honesty is a goal in director-actor and actor-actor relationships because it is the basis for trust and a truly creative working relationship. Every committed actor is looking for a director who can lead the way across new thresholds. This is development not just in acting, but in living. If you can perform this function, that actor will place great loyalty with you and be your best advocate to other actors.

ANNOUNCING CASTING DECISIONS

When you make your final decisions, personally notify and thank all who have taken part. This signals your professionalism and maintains your good standing in the community. Needless to say, rejection is painful, and all the more so for those who made it to the final round. Actors are used to rejection, and someone who does it thoughtfully and sensitively is someone worth trying again in the future. Filmmaking is a village, and your reputation is important when you return to the well.