CHAPTER 24

DIRECTOR AND ACTOR PREPARE A SCENE

For collaborative work to be truly effective, actors and the director should each work alone on the text before trying out a scene together. Their preparatory work will overlap, creating checks and balances in which action, motivations, and meanings come under multiple examinations. This helps avoid omissions and draws usefully partisan perceptions from the actors. Their viewpoints may not all be compatible with yours or each other's because each sees the world of the text more from their own character's perspective. The director leads the process of coordinating and reconciling these viewpoints, making it a creative dialogue rather than a battle of wills. For this the director should be evenhanded, holistic, and speaking for the needs of a general audience.

Following are the responsibilities that director and actor bear at the outset of rehearsal. If this seems unduly weighted toward the intellectual, much will become instinctive once you gain experience.

THE DIRECTOR PREPARES

GIVEN CIRCUMSTANCES

Know the script so you're quite certain what locations, time frame, character details, acts, and so on are specified and what other detail is implied or must be invented by director and cast.

BACKSTORY

Using your intimate knowledge of the script, infer the backstory, that is, the events preceding the script's action. Biographical details that substantiate the backstory fall into the domain of the individual character's biography, which is best generated by the actor playing the part. Directors need to be ahead of the game if the cast is to consider them authoritative.

NATURE OF CHARACTERS: WHAT EACH WANTS

It isn't enough to know what a character is; you must know what each character wants and is trying to get or do. This gives the character not just a fixed, static identity worn like a monogrammed t-shirt, but an active, evolving quest that mobilizes willpower to gain each new end, moment to moment. There is a great difference between “Paul is afraid” and “Paul's fear makes him try to deflect the policeman's attention away from his suitcase.” In the static example, the actor playing Paul has only generalized fear to work with, while the active description provides a series of definite ends to gain, each specific to the moment. A person's acting is transformed by a succession of limited, precise goals because it transforms the character into someone dynamic who shows new evidence of inner life at every step.

COMMUNICATING THE NATURE OF ACTS

Screen actors must develop behavior authentic to their characters and situations, for each right action, no matter how small, helps to create a rich and unique identity for its doer. An evocative simile or analogy gives a precise and imaginative coloration to an action or line. Verbal labels become a potent way to direct as you help each actor decide what works. To say that a man “leaves the table during a family feud” is not enough, for it provides no special information. But naming it his “tactical retreat” or “the first step in leaving home” makes it memorable and specific. A possessive mother's behavior when receiving her son's fiancée for the first time might be called “the snake dance,” and a son entering a funeral parlor where his father lies dead might be “crossing into the underworld.”

THE NATURE OF CONFLICT

The engine of drama is conflict, so the director must know precisely how and where each situation of conflict develops. The classic descriptions and their modern equivalencies are:

- Man against Nature (conflict between a character and the situation)

- Man against Man (conflict between characters)

- Man against Himself (conflict between the opposing parts of a character)

For conflict to exist in a dramatic unit (or in a larger unit such as a whole scene, of course) you must define its pattern of oppositions so you can orchestrate them. We'll use my father and his contraband sugar in “Graphing Tension and Beats” from Chapter 17 as an example:

| Define the unit's… | By asking … | Example |

| Situation | What, when, and where? | During WWII a young sailor called Paul is leaving London docks with contraband sugar hidden in a suitcase. |

Whose experience are we sharing? |

The sailor's | |

Secondary point(s) of view as resource |

Who else's viewpoint might we share? |

(1) Bystanders (2) Policeman (3) Hungry seagulls |

| Main problem | Main problem Main problem |

He wants to get it safely home to his family. |

| Conflict | Where is the main conflict? |

Though afraid of breaking the law, he wants to bring home a special treat to his family. |

| Obstacle | Obstacle that he or she faces? |

Just when his suitcase bursts he encounters a policeman. |

| Stakes | The price of failure? | If he's caught he may go to jail. |

| Complications | How do the stakes rise as the situation moves toward the apex or crisis point? |

The policeman seems helpful, but may be playing cat and mouse. He ties up the suitcase while Paul sweats. Paul starts walking away. Has he gotten away with it? He walks jauntily, in dread of hearing “Stop!” |

| Beat | How does a main character's consciousness change? |

Turning into the next street, he realizes that he is free. |

| Resolution | How does the situation end? |

At last he can breathe freely and look around him again. |

The three-act concept works well here, even in the smallest dramatic unit. It provides a wonderful set of tools for developing dramatic focus and tension. Try applying it to these situations:

- Striking a match in the dark

- Getting a locked door open in an emergency

- Getting a picky cat to sample a cheaper brand of food

- Getting an injured person across a rickety jungle bridge

- Finding a banknote in a crowded street

- Finding gravel in your shoe on the way to the altar

- Losing your partner in a supermarket

- Waking up in no man's land during a battle

- Practicing a seduction that almost works

Approached with dramatic insight, almost any situation can be developed into a fine short film and can be any genre—farce, tragedy, domestic realism—anything you like.

The dramatic unit's course has been usefully likened to the cycles of an internal combustion engine (John Howard Lawson, Theory and Technique of Playwriting, New York: Hill & Wang, 1960).

1. The piston draws in explosive gases (exposition, setting the scene)

2. Compression stage and building of pressure inside the cylinder (rising action)

3. Ignition at maximum pressure followed by explosion (beat, or climax if it's a scene)

4. Motor is forced forward into a new cycle of intake, compression, and explosion (resolution leading to next dramatic unit or scene)

This diagram works equally well for a single beat inside a dramatic unit, or to represent a complete scene with its build, climax, and resolution.

DRAMATIC TENSION AND FINDING BEATS

For this section you may first want to refresh your memory by reading the end of Chapter 1 beginning with the section, Beats, the Key to Understanding Drama.

A situation of tension between two individuals is like a fencing match—much strategic footwork and mutual adaptation punctuated by strikes. Each strike threatens to alter the balance of power and puts the match's likely outcome in a different light. Likewise in drama, a scene's nature and possible outcome alter with each impact or beat. Whenever a character feels a strike, it alters the balance of power. And this moment of altered consciousness has a heightened significance for at least one character. Each beat is a moment of “crisis adaptation,” and there may be one or many per scene.

CHARACTERIZING THE BEATS

In Chapter 1, we spoke of assigning a function to each beat, and that they can be expected to belong in one of these categories.

1. Plot Beats

| a. Story beat: | Advances the story, often connected to the disturbance or complication |

| b. Preparation beat: | Establishes the beginning of a sequence or provides foreshadowing |

| c. Expository beat: | Provides information about past circumstances |

| d. Crisis beat: | Presents conflict |

| e. Mood beat: | Establishes emotional circumstances |

| f. Reversal beat: | Reverses action (this may well be associated with a plot point) |

2. Character Attitude Beats

3. Character Thought Beats

| a. Emotive beat: | Expresses what a character feels |

| b. Reflective beat: | Expresses what a character concludes, considers, or discovers |

| c. Informative beat: | Presents information relevant to the (film) |

| d. Exaggerational beat: | Expresses maximizing or minimizing of a topic |

| e. Argumentative beat: | Contains conflict |

Characterizing each beat and classifying it according to plot needs, character attitudes, or character thoughts will focus what needs to happen in each beat. It should also consolidate your sense of the scene's trajectory, explain the development of a character's will, and clarify what effect you intend for the audience. Tagging each beat with a characterization may just as easily show unwanted reiteration and thus explain why a portion of the scene suffers from aimlessness. It's worth trying, but don't worry if you can't make sense of your screenplay using these particular tools.

FINDING THE DRAMATIC UNITS

Between one beat and the next is a transition that includes winding down from the old beat and winding up to the new. This, in the barometric language of drama, is the falling action of the old unit and the rising action of the new. All communication involves both intellectual and emotional modes of operation. Beware seeking to control your audience intellectually. To direct, you must be able to enter the emotional realities of each character, see through their eyes, feel their feelings and changes. The audience's ideas change deeply only when they are emotionally engaged.

Each dramatic unit can be minutes or seconds long.

- Find the beats. First identify the beat points in your script and see how the scene's forward movement becomes a series of dramatic thrusts at the audience's emotions. This waveform is often most palpable in domestic comedy. It can be predictable and manipulative or done so well that it becomes movingly true to human life. The difference is a matter of honesty, purpose, and taste both in the writing and the playing.

- Know what kind of beat it is.

- Determine the dramatic units. If a scene has three beats, it probably has three dramatic units. Each beat is a high point, and one of them is probably the scene turning point, or obligatory moment.

- Find the subtexts and nominate functions for each dramatic unit. Good drama is like machinery: Everything has a purpose and a function. Everything in a machine has a name; give names and functions to each part of your dramatic machinery. It will make you a good director.

IDENTIFYING SUBTEXTS

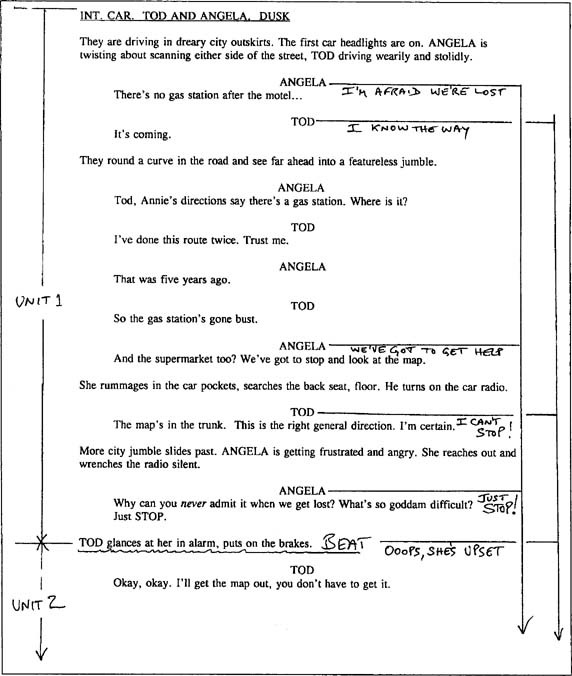

Figure 24-1 is the first page of a scene in which two characters get lost while driving in a city's outskirts. It shows a dramatic unit with its beat typically marked up. Husband and wife have a fight because Tod, as the typical male, won't stop and look at the map. The beat comes at the pivotal moment in which Tod realizes that Angela is seriously upset and that he must do something differently. There are several steps on the part of each character toward this moment, and they are decided by making an analysis of subtexts. A subtext is the underlying truth behind what the characters actually say or do. The beat has been defined in handwriting, and the steps in the subtext as it ramps up to the beat are all characterized with an interpretative tag.

See if you agree that:

- Angela's first three lines are all fueled by the same underlying idea, “I'm afraid we're really lost.”

- Once she realizes their directions mention a supermarket, and that neither this nor the gas station are anywhere to be seen, her subtext changes to “We've got to get help.”

- Tod makes adjustments to Angela's increasing frustration, and his will is pitted against hers.

- The beat comes when he realizes he's let things go too far. Typically, there's always a significant action at the obligatory moment. Here it's when he changes his mind and stops the car.

- At this point, a new dramatic unit begins.

Trained actors know how to do this work, either instinctively or deliberately with a pencil, as I did. Untrained actors won't have the first idea about this stuff, and you will have to work with them tactfully until they understand both the method and its importance. Putting a screenplay on the block reveals how tight or loose its cabinetry is and what you and your actors must do to fix it. Learn this by heart:

- Dramatic analysis is vital because it can define a clear set of actable steps.

- Each new step is a new action fueled by a new volition and emotion.

- A character's complex of emotions is like a melody: It only exists if the notes are sounded in sequence, not all at once.

- Acting is sequencing one clear intention after another, one clear and appropriate action after another, one clear emotion after another.

Though this is true to life, only trained actors understand it. The layman gets it wrong because he remembers a situation in abstract, summary form in which all the fine, distinct experiences have been mulched together into a static description. This is what you, as a director, must so often work to tease apart and make dynamic.

To strengthen your skills, make a point of observing—in yourself as well as in others—how realizations, emotions, and actions are sequenced in real life. After observing actuality you won't accept the mishmash rendering anymore.

To feel secure, you must always be ahead of your cast, breaking down each scene and knowing precisely what drives each step forward for each character within each unit. You may learn something when you review the work the actors have done on their own, but they will be deeply impressed that you understand their parts so well. From preparation you derive conviction about what you want, and from this comes your authority to direct.

Actors seek clarity and decisiveness from their director, as well as clear, detailed feedback about their work, but they feel they never get enough. The director who comprehends what each actor is giving, who can describe it accurately to the cast, is like the orchestral conductor who hears every instrument and can tell the fourth cello afterward what wrong note she played. This is not a skill anyone is born with, but something you must work mightily to acquire. Doing your homework diligently on the script is the absolute foundation.

CHANGES IN A CHARACTER's RHYTHM

Every character has rhythms for speech and action. These vary according to mood (whether, for instance, the character is excited or tired) and the pressures exerted by the situation. It is an actor's responsibility to keep the character's rhythms distinctive and varying according to the character's inner state, which will always change if he or she has a beat point. Put another way, monotony of rhythm usually means that the actors are performing by rote, so you must know where to expect rhythmic changes. The problem has become acute when all the actors in a scene fall into the same mesmerizing rhythm.

OBLIGATORY MOMENT

One of Lawson's intake explosion cycles described previously will be the scene's obligatory moment, that is, the major turning point for the scene. This is the moment for which the whole scene exists. Determine what is the obligatory moment by seeing whether the scene still makes sense without it. If you axe the obligatory moment, the scene becomes disabled or redundant. Make sure your directing has the right focus by being sure what each scene's obligatory moment is.

NAMING THE FUNCTION OF EACH SCENE

Like a single cog in the gear train of a clock, each scene in a well-constructed drama has its correct place and function. Defining how power courses through the piece, scene by scene, enables you to interpret each scene confidently and to know how it feeds impetus into its successor in the larger pattern. Giving a tag name to each scene defines it for you and lets you communicate its nature to cast and crew. Dickens' chapter titles from Bleak House make good examples: “Covering a Multitude of Sins,” “Signs and Tokens,” “A Turn of the Screw,” “Closing In,” “Dutiful Friendship,” and “Beginning the World.” Ideas about mise en scène and scenic design flow effortlessly from charged descriptors like these.

THEMATIC PURPOSE OF THE WHOLE WORK

The director decides and shapes the authorial thrust of the whole work. This interpretation must remain consonant with the screenplay's content and be accepted by the cast. Unlike a published play, a screenplay is not a hallowed document and directors often take considerable liberties with one after a property (a revealing name for a screenplay) has been acquired, which causes much bitterness among screenwriters. Once the piece is in rehearsal and on its way to shooting, the director alters the thematic purpose of the whole at his or her peril.

THE ACTOR PREPARES

A NOTE TO DIRECTORS

Many concepts important to actors are similar to those mentioned for directors, and so they appear in the following section in abbreviated form. Though I have written in the third person as if myself addressing an actor, these notes are for your instruction. Any trained actor should know all this anyway.

By the nature of their work actors are vulnerable, so avoid openly top-down instruction. When you must instruct, couch it respectfully as something to try. This is particularly important when you enter areas of technique or emotion that you haven't experienced yourself. Your function as a director lies primarily in recognizing the authenticity of the result, not dictating how the actor gets there. So from here on, my language addresses actors.

BACKSTORY

Know the events that brought your character to the script's present.

YOUR CHARACTER's GIVEN CIRCUMSTANCES

Know at every point what circumstances and pressures determine your character's physical and mental state.

BIOGRAPHY

Make up a full life story for your character that supports the backstory details implied by the script. This ensures that you know a great deal more about the character you are creating than is required, and that everything your character says or does has proper roots in the past. Without this integrity of experience and motivation, your character will lack depth and credibility. Your director will often question you during rehearsal about your character's background, always probing what is not yet coming across well.

BE ABLE TO JUSTIFY EVERYTHING YOUR CHARACTER SAYS AND DOES

You should know the specific pressures motivating your character's every action and line. This process of justification has already been used to build your character's biography, and this biography in turn helps govern your character's choices and decisions. The script usually contains the relevant clues, but occasionally your character's action must be completely defined by you and your director.

DEFINE EACH ACTION WITH AN ACTIVE VERB

Onscreen actions are the most eloquent expressions your character ever makes, so the linguistic tags by which you plan them matter very much. Take this poor example: “A woman is seen stepping away from her tipsy husband in embarrassment at a party when an indiscretion passes his lips.” This flat description uses the passive voice and is minimally informative. An enterprising actor might describe the action as, “sidestepping the landmine,” “she absorbs a punch in the gut,” “she springs toward the bar,” or “she reels aside after stepping in filth.” These descriptions employ active verbs to illuminate the behavior and its motivation.

What about common actions like opening a closet door? To perform the action in general, that is, without a specific motivation, is false to life. Giving even small actions an active description helps invest each with a specific identity and meaning. For instance, “He eases the door open” shows caution and perhaps apprehension. Substitute such verbs as jerks, rips, shoves, barges, slides, elbows, flings, dashes, heaves, or hurls and you have a spectrum of relationships between person and door, each particularizing the action to great effect.

Filmmakers expect actors to remain consistent over many takes and many angles, and a single 3-minute scene may take a whole day to shoot. Consistency becomes a major problem for the actor, especially if inexperienced. Verbal tags help stabilize this situation, especially as fatigue sets in. Make them part of your preparation and each action will remain clear in quality and motivation so you remain emotionally consistent. Having tags to hand also makes you a joy to work with because communication with your director is quick and clear.

WHAT IS MY CHARACTER TRYING TO GET OR DO?

Answering this commonplace little question is the key to persuasive acting. In everyday life most of us are unaware of how unceasingly inventive we are in pursuing what we want. Instead, we see ourselves as civilized, long-suffering victims who sacrifice happiness and fulfillment to the voracious demands of others. But you are not called an actor for nothing. Your character is always trying actively to get what he or she wants (a smile, a cup of coffee, a sympathetic reaction, a rejection, a sign of guilt, a glimpse of doubt) using a strategy peculiar to your character alone, as he or she tries to realize the desire of the moment. As circumstances alter, the character's needs change and adapt. Incidentally, being active like this is the only viable method to portray a passive person, who differs only in strategy.

WHAT ARE OTHER CHARACTERS TRYING TO DO TO ME OR GET FROM ME?

Your character must remain alive to the real and unpredictable chemistry of the acted moment. If you scan the other characters for signs of their will and intention, your character will be fresh and alive. In real life this process is constantly within us, happening automatically and unconsciously. But in a role, these reflexes must be deliberately patterned until your character's actions and reactions are internalized. Then a scene shot in untold takes and angles can still be alive at the end of a long working day because you and your partners are still working from the actual, not just from the rehearsed.

KNOW WHERE THE BEATS ARE

See the section on “Finding the Beats” in the previous director's portion of this chapter, but be aware that as an actor sustaining a single consciousness, you sometimes see peaks of consciousness in your character that have been overlooked by your director. Don't be afraid to play these or be an advocate for your character.

HOW AND WHERE DOES MY CHARACTER ADAPT?

Every character has goals to pursue or defend and will read either victory or defeat into the course of things. To accommodate changes in other characters, you must make strategic adaptation within the frame of the writing. Spotting where and how to make these adaptations helps build a dense and changing texture for your character's consciousness. Maintaining this is so much work that you can stay effortlessly in focus throughout many takes.

KEEP YOUR CHARACTER'S INTERIOR VOICE AND MIND'S EYE GOING

In real life, people are enclosed in their own ongoing thoughts, hopes, fears, memories, and visions, some of which are occasionally verbalized as an interior monologue. The good actor builds and maintains his or her character's stream of consciousness or interior action. Hear or even speak your character's conflicting thoughts internally. Summon up mental images from your character's past, remember and imagine in character, and you will be continuously convincing and interesting to an audience. Another consequence is that your actions and reactions will become consistent and true in pacing. A properly structured consciousness in turn liberates genuine feeling. The actor's art is nothing less than maintaining a disciplined consciousness, and this is why acting is so difficult and psychically demanding.

KNOW YOUR CHARACTER'S FUNCTION

Know all your character's objectives. Know what the scene and the whole film are meant to accomplish and what your character contributes. Don't work to inflate or change it.

KNOW THE THEMATIC PURPOSE OF THE WHOLE WORK

The responsible actor knows that characterization must merge effectively with the thrust of the whole work. You must cooperate, not compete, with the other actors to realize this. Your director is the arbiter of these matters, and also your only audience. Seek feedback from the director alone. Ignore anything told you by crew, onlookers, or other actors.

REHEARSING WITH THE BOOK

EARLY WORK WITH THE BOOK

By now the actors should have done their homework. You (the director) have not yet given them the go-ahead to learn their lines because, as we have said, this leads to actors internalizing an undeveloped and unproven interpretation. Learning lines also fixes an actor's attention prematurely on words when, for screen acting, behavior (of which language is only a part) is preeminent.

The cast may be bursting with questions and ideas. Run through scenes “with the book” (that is, actors reading from the script) and see what each actor's conception of his or her character and of the scene is. You should never have to struggle to understand something. If the words or actions don't communicate, something is invariably wrong with the actor's understanding. Early rehearsal should be geared toward finding the focus and interpretation you want. At this stage, learning the scene is more important than learning lines. Character consistency is an issue because it requires reconciling a character's actions in one scene with those in other scenes. Expect discussion and disagreement over the nuances of motivation behind the action and dialogue. This is not people subverting your authority, but the heady and untidy excitements of discovery.

REHEARSAL SPACE

It is an advantage to rehearse in the locations to be used, but this is often impractical. Make still photos to show actors what the location is like. This helps them imagine the proportions in which the scene is to take place and feeds the overall image of their characters' lives. Rehearsal itself often takes place in a large, bare space that is borrowed or rented. Indicate placement of walls, key pieces of furniture, doors, and windows with tape on the rehearsal room floor.

The advantage of a minimalist rehearsal like this is that there is nothing to distract from attention to the text and its characters. The disadvantage is that its abstract quality can lead some to compensate by projecting theatrically toward an imagined audience.

WHICH SCENES FIRST?

At the first rehearsal you will probably cover one or two scenes chosen for their centrality to the piece as a whole. These should emerge naturally while you made your dramatic breakdown and definition of thematic purpose. Work on these, and the turning points within them will provide a sure framework for other linked scenes. Like laying the foundations for a building, rehearsal deals with important issues first.

MOVEMENT AND ACTION

Although reading from a text hinders actors from moving with freedom, get each cast member to develop actions that reflect his or her character's internal, psychological movement. These are vital at the beats. For example, a man being questioned one evening in the kitchen by his possessive mother decides he must confess he is engaged to marry. The text reveals what he says, but it's from what he does that we know how he feels during these stressful minutes. The screenplay does not specify. Does he start drying the dishes, repeatedly handing items to his mother so her hands are never empty? Let's try that to see how it works. When she becomes especially probing, he goes silent, so maybe he should let the water out of the sink, watching it drain away. As the last of it gurgles away, he turns and blurts out his secret. The domestic scene, the way he purges himself of the family china, the water running away, all combine both as credible action and as metaphors for the pressure he feels to act on a “now or never” decision.

Spontaneous invention first produces clichés, so the director must demand fresher and less predictable action from the cast than the example I have invented here.

While hampered by the book and unable to truly interact with each other, actors' readings will remain inadequate, so content yourself with rough sketch work at this stage. As soon as you are satisfied that character, and motivation and the right kind of ideas for action are agreed, instruct the cast to learn their lines for a scene.

REHEARSING WITHOUT THE BOOK

When work begins without the book, watch out that the increased meaningfulness of the lines don't usurp the development of physical action. Encourage the actors to approach the scene from a behavioral rather than textual standpoint. This confirms the importance of having a clear idea of the setting—what it is, what it contains, and what it represents to the characters themselves. Insist on exploring the meaning and spirit of lines, not on their strict accuracy. You can always tighten the readings later. You'll find Chapter 21, Exercise 21–9: “Gibberish” a useful resource here.

TURNING THOUGHT AND WILL INTO ACTION

Only a few significant actions are specified in the average script, and unless director and actors approach the script as an extremely spare blueprint requiring extensive development, characters will move into position, deliver their speeches in an overwrought manner, and be done. This reliably produces a hollow, unconvincing movie.

The true power behind both speech and action is will. Imagine you have a domestic scene between a mother and son under development. It might well develop as follows: When Lyn tells her son Jon that the car bumper is twisted, she is trying to make him feel shocked and guilty. You and your cast know this from the rest of the script, but you want to translate this into action. At the beginning of the scene, Jon hears his mother walk to the garage, but instead of hearing her drive away, he hears her footsteps return. Now she must force her angry state of mind upon her son. You get your actress to slow her entry and make it wordless, accusatory. She stands in the door looking at him. Now he must repel or subvert the pressure she is applying. The actor tells you he feels that his character wants to be busy. You decide he is building a model car and painting the kit parts, keeping this up so he can avoid his mother's accusing gaze.

How does she command his attention? From intuition you suggest to her, “Try throwing the car keys next to the box of parts.” This rudely interrupts his evasive activity and creates a charged moment culminating in a beat as their eyes meet. You and your actors are elated because you feel instinctively that you have created a strong moment. Now when the mother says, “The front bumper's all twisted,” she is no longer supplying information but pushing home an accusation that began with her silent re-entry. We no longer have words as neutral information or words initiating action. We now have action culminating in words that themselves seek an effect. Driven by conscious needs, words become a form of action seeking the gratification of a reaction. This is why a well conceived dialogue contains much that is verbal action.

Good actors and good directors try to develop those pressures in the characters that produce dialogue. And in good writing, all dialogue is specific and acts on the person addressed. Thus lines of dialogue become verbal actions. Dialogue supplies momentum by energizing action in the person addressed.

Developing a scene is therefore more than knowing the dialogue and where to move on such and such a line; it is working out a detailed flow of action to evidence the internal ebb and flow of each character's being. Primarily this is each actor's responsibility, but final choice and coordination is the director's job. Proof of success is when an audience senses what is going on without hearing a word. I do a lot of international travel, and I seldom bother listening to the sound tracks of in-flight movies. Instead I watch them silently to learn as much as possible from their non-verbal side.

SIGNIFICANCE OF SPACE

How characters use space in this flow of action becomes highly significant. Continuing the previous scene, the mother and son are half the room apart when she enters, but she walks up to him in silence. The pressure from her proximity can cause him to make a painting error, and he lays down the work, looking up at her accusingly. “It's not my fault; you parked it too close to the wall,” he says, continuing to look up. She turns away in frustration and turns on the TV. Both stare at the silent picture for a moment or two, hypnotized and taking refuge in habit before they return to the divisive issue of how the car got damaged.

It is now the action rather than the dialogue that is eloquent of their distress, yet no more than a few bald lines of dialogue appear on the page. Action has been created to turn implication into behavior—behavior being the ebb and flow of will. If some dialogue is now redundant you can cut it. So much the better.

A CHARACTER'S INNER MOVEMENT

If you break down a single moment of inner movement in a character, you find four definite steps:

1. Feels Impact: An expectation (someone's words or actions) impacts character's consciousness.

2. Sees Demand: This, filtered through his temperament, mood, and current assumptions, is translated (correctly or otherwise) into a demand (“She wants…”).

3. Feels New Need: Forms a new need (“Now I must…”).

4. Makes Counter-Demand: The new need is expressed through an action (physical or verbal) that the character expects will get fulfilling results.

Commonly when an actor looks unconvincing, steps 2 and 3 are absent because the inner process isn't happening. Let's look at an example, a discussion between a couple about an outing they have planned.

It is early Friday evening. Brian and Ann disagree about which movie they should see. She wants them to drive out to the farther cinema and see a new comedy. Not really wanting to go out, he says the comedy was not well reviewed, so they might as well go to one of the nearer films. She finds the newspapers and says that, on the contrary, the movie got three stars in both papers. Looking at him, seeing he is not changing his mind, she turns abruptly and moodily kicks her shoes into the closet, saying that he never wants to go out with her. He looks concerned and protests that it is not true. They end up going to the movie she wanted to see, and he enjoys it more than she does.

Let's analyze the moment when Ann suggests the film at the faraway cinema. Brian, whose job we know requires him to make a long commute, now wants to watch TV and relax. His interior changes call for something like the following interior monologue:

Feels Impact: “Drive 10 miles to see a movie when I could settle down and watch the news? Oh boy, this is really something to come home to.”

Sees Demand: “It's her day off, and she wants us to do something together. It's the old complaint that I never consider her situation, but that's not true….”

Feels New Need: “I really can't get back into that traffic again for 40 minutes. I've really got to put this off somehow…. It's not even a decent movie.”

Makes Counter-Demand: (Speaking to Ann while looking ineffectually through the accumulation of newspapers) “You know, I seem to remember that David What's-his-name in the Times only gave it one star.”

Brian does not signal his feelings, but instead makes a direct, action-oriented leap between what he perceives to be happening and what he must do to cope with it. In general our feelings are followed by action and only require conscious examination when we are in internal conflict. Brian is not conflicted until he realizes that Ann is nearly crying with disappointment and frustration. To make him realize this and to move him to action will require that we first see Ann's changes and his adaptations to what she feels and does.

Of course, not all human interaction centers on disagreement, but it often happens in drama because all drama centers on conflict, no matter what the genre. Even when characters appear to be in harmony, one may be buying time, that is, going along verbally while turning the whole matter over in his or her mind. Because inner states always find outward expression, it is important to find a fresh, subtle action to evidence (not telegraph or illustrate!) what the character is experiencing inside. Only troublesome moments need to be worked over in fine detail like this one.

ADAPTATION

In the adaptation between characters, we have to picture something like two people trying to stand up in a small boat. Each must compensate for the changes of balance caused by the movements of the other. This causes many feints, experiments, surprises, and mistakes. A script says nothing about these because it is the actors' work to create whatever adaptations lead to the next line or specified action. This is not as difficult as it may sound because we are all experts in recognizing what is or isn't authentic to characters in a situation. The actors suggest and the director accepts, rejects, or modifies.

WHEN A CHARACTER LACKS AN INNER LIFE

Trained actors know how to maintain their characters' inner lives, but for others you have to ask for an inner monologue, that is, the conscious internal enunciation of the characters' thoughts and perceptions. The symptoms of an actor without an interior life are that the character:

- Seems to have no credible thought process

- Comes to life only when he or she has something to say

- Switches off while waiting for the next cue

- May be actually visualizing the script page—certain death for movie acting

A sure way to shift an actor out of this mode is to request an out-loud thoughts voice between lines, as in Chapter 22, Exercise 22–3: “Improvising an Interior Monologue.” This is also a superb way to examine a point at which an actor repeatedly loses focus or when you suspect there is a skewed understanding of a certain passage.

REACTIONS

Working in a big studio, I noticed that the better actors could make reaction shots interesting, while others could not. An actor's character remains alive during reaction times only if they remain internally active and in character. If an actor's reaction shots are disappointing, attend to what they are doing within.

USEFUL MISPERCEPTIONS

As in life, dramatic characters often make errors of judgment for a wide range of reasons—out of nervousness, fear, misplaced confidence, wrong expectation— and read a fellow character's intentions wrongly. A character laboring under a misapprehension can produce very good dramatic mileage. Other equally productive misapprehensions come from a characters' unfamiliarity with the culture or with the personality of the antagonist, and to this we could add inattention, preoccupation, partial or distorted information, habit, or inebriation, to name just a few other reasons for myopia. Misperception is a fertile source for comedy (think of Basil Fawlty in the Fawlty Towers series), and just as easily it produces tension by provoking others into action that, far from neutralizing a situation, drives matters forward to new heights of revelation about the characters' differences and inner lives.

The work of Harold Pinter, like that of many modern dramatists, exploits the tensions between the characters' surface conformity and the dark, groping, private worlds existing beneath. In The Dumbwaiter, two hired assassins are left waiting interminably in a disused kitchen for further instructions. The lengthening wait, punctuated with bizarre, unfulfillable requests sent down in the dumbwaiter, acts upon the two men's private fears and distrust. While trying to maintain the faltering normality of their working partnership, each is gnawed by increasing fears, and we see them regress out of sheer insecurity.

The subtext deals with masters and servants, order and chaos, security and insecurity. It presents the characters as an analogy for mankind waiting nervously to learn God's will. But the piece can misfire as a light comedy of manners if director and actors fail to play the subtexts.

EXPRESSING THE SUBTEXT

An actor must develop not just an idea of a subtext but the physical expression of it, so he or she enters an intensive, created world where thoughts and feelings of the character can be lived out. The actor creates the character, yet also is that character and so can speak for them and be guided by a growing intuition about what is authentic. This means finding what action (both given and received) truly sustains the flux of the character's emotions. Conversely, it means sensing what is going against the character's grain and which he needs to examine and change. Like ambitious parents to their child, each actor is shepherd and champion for his or her own character. The director encourages this, but also deals evenhandedly with the rest of the cast so that a spirit of destructive competition doesn't set in.